According to statistics, there are more than 7,000 languages worldwide. The origins, development, and locations of these languages remain a scientific mystery.

How is language formed? What was the first language of humans? Many have pondered these questions without clear answers. Throughout history, people were not only curious but also dared to conduct experiments to unravel such mysteries.

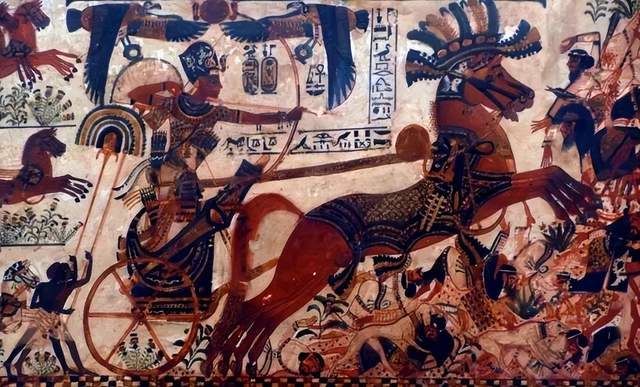

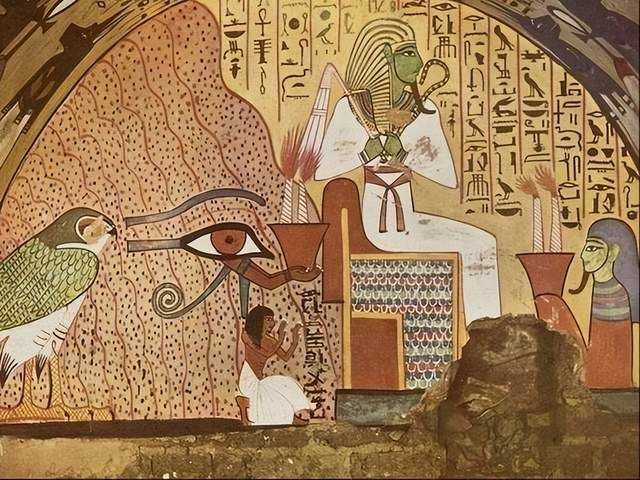

In the book 'History Volume II' by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, around 2,600 years ago, a Pharaoh named Psammetichus in ancient Egypt was curious about the world, especially the origin of language. He consistently asked about the 'primitive language' (the first language) of the world and the oldest nation on Earth.

Certainly, the Pharaoh had reasons to doubt. Finding the answers was a way to prove the superiority of his nation and achieve rightful claims to rule over other nations.

Ancient Egyptians always believed they were the most ancient civilization. They claimed their language was the origin of human language, and other nations and political powers were descendants of ancient Egyptians. They considered themselves the oldest people in the world. Therefore, Pharaoh Psammetichus aimed to substantiate this belief.

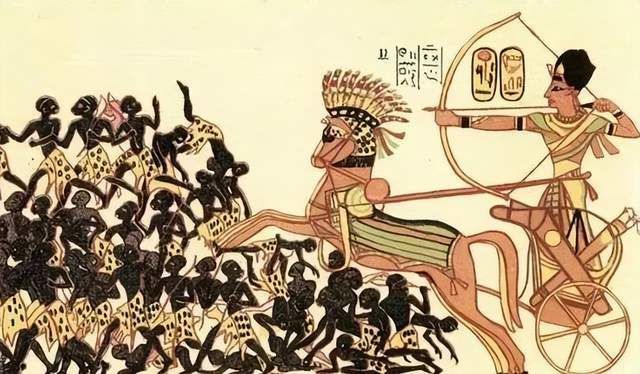

To prove this assertion, Pharaoh envisioned utilizing language as a means to distinguish and establish their national identity. By demonstrating that ancient Egyptian is the 'root language,' the first language globally, they aimed to affirm ancient Egyptians as the oldest nation, asserting their language as the primary language of humanity and the origin of all ethnicities. This strategy served to significantly boost their national pride.

Additionally, if successful, ancient Egypt could declare that individuals from other ethnic groups evolved from ancient Egyptians. This could lead to a demand for the legal legitimacy of the ruling regime over these ethnic groups. Pharaoh could assert that even though those from different ethnicities no longer speak ancient Egyptian, they are still descendants, granting him the right to rule over them 'legitimately.'

To achieve these goals, Pharaoh needed to substantiate his hypothesis. Thus, this Pharaoh ordered the initiation of an experimental procedure.

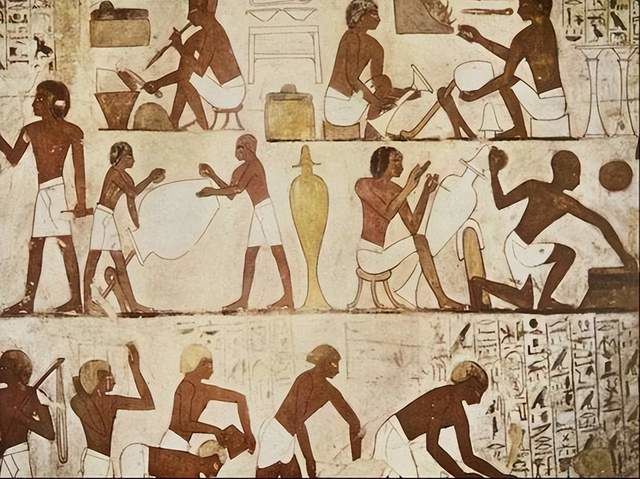

Firstly, they would locate two newborns, assigning one to a shepherd for upbringing in isolation, far from the crowd. One of them would be entrusted to a woman believed to be tongueless, nurturing the child from birth.

The shepherd, responsible for the upbringing of the infants, would refrain from teaching them to speak, avoid speaking in their presence, and prevent any external contact. This ensured their complete isolation from the outside world, preventing exposure to any human language before they acquired the ability to speak.

During this period, the infants would live in a tent without human interaction, relying on the shepherd for sustenance. The shepherd would observe their behavior and promptly report to Pharaoh once the two infants could articulate any language.

Psammetichus' curiosity was focused on the first words a child could speak without being taught or exposed to any language. He aimed to determine if these words were in ancient Egyptian.

Why? This Pharaoh believed that the language spoken by untaught children was undoubtedly the original, the first language bestowed upon humans by divine entities. If the child spoke in ancient Egyptian, it would confirm it as the oldest language globally, establishing Egyptians as the world's oldest people. This indirectly implied that other nations worldwide were descendants of ancient Egyptians.

Over time, the two children grew up in a language-free environment, sharing meals, sleeping, and playing together. Years later, when the shepherd opened the door for their meal, both children ran towards him with open arms and exclaimed a word - 'Bekos' (βεκόϛ).

Hearing the children speak their first words, the shepherd immediately reported the incident, swearing he had never spoken to them or exposed them to any other language.

Upon learning this, Psammetichus felt elated and requested the shepherd to bring the children to him so he could personally hear the words they spoke. The primary objective was to understand the meaning of 'Bekos' (βεκόϛ), its language origin, and precisely where it came from.

Linguistic experts of that time had to search day and night through ancient texts and prophetic words from different civilizations.

In the end, the efforts paid off. However, the outcome left the Egyptian pharaoh disappointed. The experiment failed to prove that the language of his people was the origin of human language. Instead, it demonstrated that the words spoken by the two children meant 'bread' and the language of the Phrygian people was the newest primitive language, at least according to this Pharaoh's perspective.

Nevertheless, from a modern scientific and linguistic standpoint, the Pharaoh's experiment and viewpoint were entirely flawed. Language cannot spontaneously generate. Creating language requires humans to live in communities, involving an evolutionary and long-term accumulation process.

If a human child grows up in complete silence from birth, even with a companion, it cannot create a new language!

References: ZME; Zhihu; Sina