You've got the spark of an idea for a play script—maybe even a brilliant one. Now, the challenge lies in shaping it into a captivating narrative. While the temptation to plunge straight into writing may be strong, your play will benefit greatly from careful planning beforehand. By fleshing out your storyline and outlining your structure, you'll find that tackling the first draft becomes a far less daunting task.

The Anatomy of a Play Script

Embark on a journey of brainstorming, delving into the lives of your characters, and uncovering the core conflicts of your play. Map out the architecture of your piece, sketching acts and scenes while weaving in stage directions. Pay heed to proper formatting to ensure your script flows seamlessly, and don't shy away from revisiting, revising, and refining your dialogue and action.

The Path Ahead

Exploring Your Story's Potential

Define the essence of your narrative. While each story possesses its unique flair, most plays fit into specific categories that guide the audience in interpreting the unfolding relationships and events. Ponder over the characters you wish to portray and contemplate the trajectory of their tales. Do they:

- Embark on a quest to unravel a mystery, sometimes even entrusting others to script their journey?

- Endure a series of trials to undergo profound personal transformation?

- Experience the transition from innocence to experience, navigating the realms of maturity?

- Undertake an epic journey akin to Odysseus's legendary odyssey?

- Restore order amidst chaos?

- Conquer a series of challenges in pursuit of a goal?

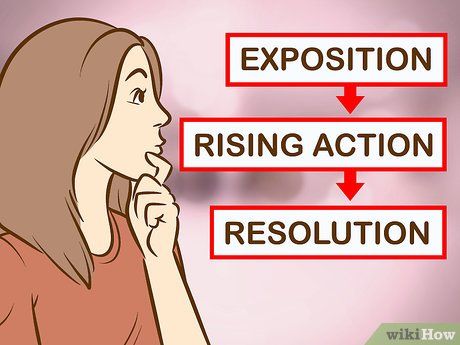

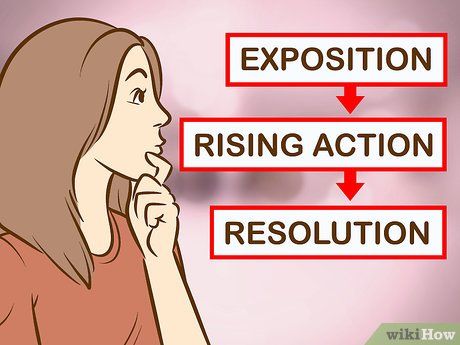

Ponder the fundamental elements of your narrative structure. The narrative arc delineates the trajectory of your play from its inception to its culmination. This trajectory comprises exposition, rising action, and resolution, each playing a distinct role in propelling the story forward. Irrespective of the play's length or the number of acts, a well-crafted narrative encompasses these components. Prioritize outlining each segment before commencing the writing process.

Determine the essential elements for the exposition. The exposition sets the stage by furnishing vital details essential for comprehending the narrative: Where and when does the story unfold? Who assumes the mantle of the protagonist? Who are the supporting characters, including the antagonist who catalyzes the protagonist's central conflict? What form does this conflict assume? What tone permeates the play—comedy, romantic drama, tragedy?

Guide the transition from exposition to rising action. The rising action unfurls a sequence of events that heightens the stakes for the characters. The central conflict looms larger as circumstances grow increasingly dire, intensifying the audience's emotional investment. This conflict may manifest as interpersonal strife (with an antagonist), external adversities (war, poverty), or internal struggles (overcoming personal insecurities). The rising action reaches its crescendo at the climax—the apex of tension where the conflict reaches its zenith.

Determine the resolution of your conflict. The resolution serves to untangle the tension built up during the climax, concluding the narrative arc. You might opt for a happy ending, where the protagonist achieves their desires; a tragic finale that imparts poignant lessons from the protagonist's downfall; or a denouement that addresses lingering queries.

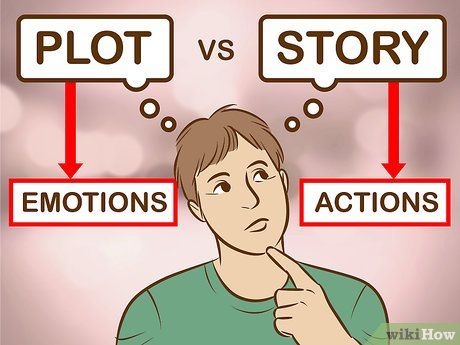

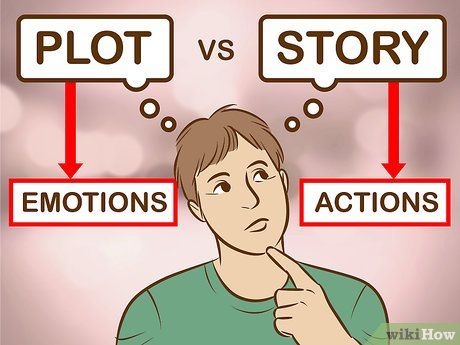

Grasp the distinction between plot and story. Your play's narrative comprises two distinct yet interwoven elements: the plot and the story. Both must evolve harmoniously to captivate your audience. E.M. Forster delineated story as the sequential unfolding of events, while the plot encompasses the logical connections that imbue these events with emotional impact. Consider:

- Story: The protagonist experiences heartbreak and unemployment.

- Plot: Heartbroken, the protagonist's emotional turmoil at work leads to dismissal.

- Forge a compelling story that propels the play's action while meticulously intertwining plot elements. This coherence engenders audience investment in the unfolding drama.

Flesh out your narrative. Before delving into the intricacies of plot, establish a robust storyline. Initiate the process by addressing fundamental queries:

- Where does your tale unfold?

- Who embodies the protagonist, and who assumes pivotal secondary roles?

- What central conflict propels the narrative?

- Identify the inciting incident catalyzing the primary action and subsequent conflict.

- Trace the characters' evolution in response to adversity.

- How is the conflict ultimately resolved, and what repercussions ensue?

Elevate your narrative through plot progression. Plot development elucidates the intricate interplay between narrative elements outlined earlier. Address pivotal questions to refine plot dynamics:

- What dynamics govern character relationships?

- How do characters engage with the central conflict, and who bears the brunt of its impact?

- How can the narrative structure orchestrate character-con conflict encounters?

- Craft a seamless progression, culminating in the climactic moment and subsequent resolution.

Designing Your Play's Blueprint

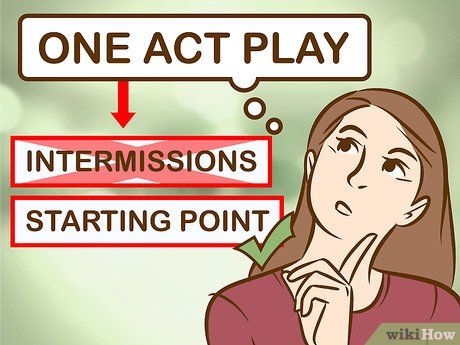

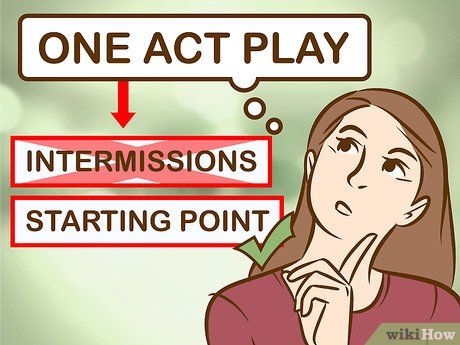

Start with a one-act play if you're new to playwriting. Before you start writing, consider the structure you want to employ. A one-act play runs continuously without intermissions, making it ideal for beginners in playwriting. Examples include 'The Bond' by Robert Frost and Amy Lowell, and 'Gettysburg' by Percy MacKaye. Despite its simplicity, remember that every story necessitates a narrative arc encompassing exposition, rising tension, and resolution.

- As one-act plays don't feature intermissions, opt for straightforward sets and minimal costume changes to simplify technical requirements.

Do not restrict the length of your one-act play. The duration of a one-act play is not predetermined by its structure. These plays can vary widely in length, ranging from as short as 10 minutes to over an hour.

- Flash dramas, brief one-act plays, can last from a few seconds to around 10 minutes. They're ideal for school and community theater, as well as flash theater competitions. Anna Stillaman's 'A Time of Green' serves as an example.

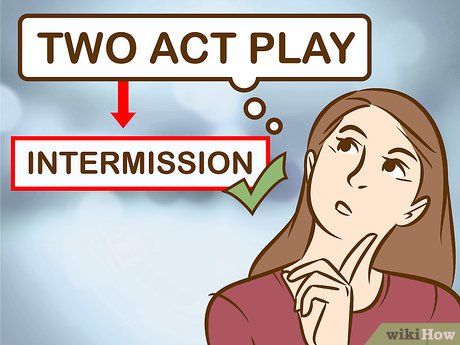

Accommodate more elaborate sets with a two-act play. The two-act play represents the prevalent structure in contemporary theater. While there's no set duration for each act, they typically span about half an hour, separated by an intermission. This break allows the audience to refresh themselves, reflect on the preceding events, and engage in discussions regarding the initial conflict. It also affords your crew time for substantial set, costume, and makeup changes. Intermissions typically last around 15 minutes, so ensure your crew's tasks are manageable within this timeframe.

- For examples of two-act plays, refer to Peter Weiss' 'Hölderlin' or Harold Pinter's 'The Homecoming.'

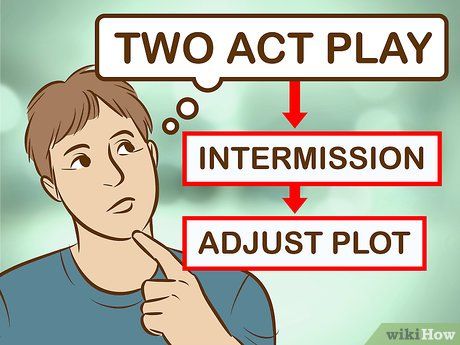

Adapt the storyline to suit the two-act format. The two-act structure entails more than just increased time for technical adjustments. With a break midway through the play, the narrative must account for this interruption, leaving the audience intrigued and eager for the second act. Structure your story accordingly to sustain tension and anticipation.

- Position the “inciting incident” halfway through the first act, following the initial exposition.

- Subsequent scenes in the first act should heighten tension, leading to a climactic conflict before the act's conclusion.

- End the first act at the pinnacle of tension, leaving the audience craving resolution during intermission.

- Commence the second act at a lower tension level, gradually reintroducing the conflict.

- Progress through the second act with escalating conflict towards the climax.

- Conclude with a resolution that eases the audience from the heightened tension established throughout the play.

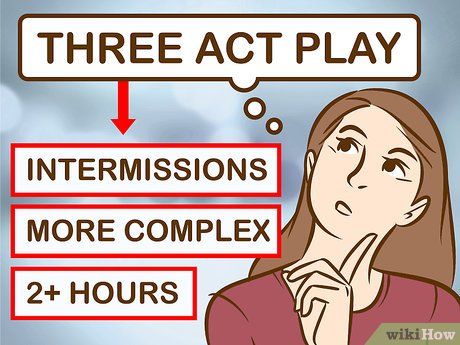

Structure intricate, lengthy plots with a three-act format. For novice playwrights, starting with a one- or two-act play is advisable, as a full-length, three-act production may demand an audience's attention for up to two hours. Crafting such a production requires considerable experience and skill. Nonetheless, if your narrative warrants it, a three-act play can be a fitting choice. Like its two-act counterpart, it accommodates substantial set and costume changes during intermissions. Each act should serve a distinct storytelling purpose:

- Act 1 introduces the exposition, acquainting the audience with characters and background information. It's crucial to engender empathy for the protagonist and establish the central conflict, ensuring a poignant emotional response as the plot unfolds.

- Act 2 introduces complications, intensifying the protagonist's predicament. Revealing crucial background details near the act's climax heightens tension, instilling doubt before the protagonist's eventual resolution. Act 2 culminates in turmoil, with the protagonist's plans in disarray.

- Act 3 resolves the conflict, as the protagonist navigates obstacles and reaches the play's conclusion. Note that not all resolutions are joyful; the hero may meet demise, yet the audience should glean insights from the outcome.

- Examples of three-act plays include Honore de Balzac's 'Mercadet' and John Galsworthy's 'Pigeon: A Fantasy in Three Acts.'

Crafting Your Play

Draft your acts and scenes. Having brainstormed narrative arcs, story development, and play structures, compile your ideas into a cohesive outline before commencing writing. Detail each act's scenes, considering:

- Introduction of key characters.

- Scene count and specific events.

- Sequential event progression for plot development.

- Technical elements such as set and costume changes.

Elaborate on your outline by penning your play. Translate your outline into the actual script, focusing initially on basic dialogue without concerning yourself with naturalness or actor movement. Initial drafts should simply capture ideas on paper, as advocated by Guy de Maupassant.

Cultivate authentic dialogue. Aim for a script that enables actors to deliver lines naturally, infusing them with humanity and emotional depth. Review your first draft by recording and listening to yourself read aloud, identifying instances of stiffness or verbosity. Remember, even in literary contexts, characters must sound authentic, eschewing grandeur for relatable discourse.

Allow dialogues to meander. Real-life conversations often stray from a single topic. While maintaining a course toward the next conflict is crucial in a play, incorporating minor diversions adds authenticity. For instance, amidst discussing the protagonist's breakup, characters might briefly debate the duration of their relationship.

Embrace interruptions in dialogue. Interruptions are commonplace in conversations, whether supportive affirmations or self-interruptions mid-sentence. Utilize sentence fragments without hesitation, akin to natural speech patterns. For example: “I despise dogs. Every last one of them.”

- Don’t shy away from sentence fragments; despite being discouraged in formal writing, they mimic spoken language effectively: “I hate dogs. All of them.”

Incorporate stage directions. Stage directions elucidate the playwright's vision for onstage actions. Employ italics or brackets to distinguish directions from dialogue. While actors infuse their creativity, specific directions aid in portrayal, such as:

- Interlude cues: [lengthy, uncomfortable silence]

- Physical movements: [Silas rises and paces anxiously]; [Margaret nervously bites her nails]

- Emotional states: [Anxiously], [Enthusiastically], [Grimacing as if repulsed]

Revise your draft diligently. Mastery in playwriting necessitates multiple revisions. Refinement occurs incrementally; don’t rush the process. Each revision should enrich the narrative depth.

- As you enhance detail, remember the power of omission. Eliminate superfluous dialogue and events, retaining only those contributing to emotional depth.

- Follow Leonard Elmore's counsel: “Try to omit the parts readers skip.” The same applies to plays.

Blueprint for a Play Script

A Model Outline for a Play Script

A Model Outline for a Play Script

Insights

-

Most plays adhere to specific timeframes and settings, so maintain consistency. For instance, a character in the 1930s could place a telephone call or dispatch a telegram, but wouldn’t have access to television.

-

Conduct a live reading of the script with a small audience. Plays hinge on language, and their potency—or lack thereof—becomes readily apparent when spoken aloud.

-

Iterate through numerous drafts, even if you're content with the initial one you produce.

Cautions

Rejection eclipses acceptance by a considerable margin, but don't lose heart. If one play faces disregard, embark on another project without faltering.

Safeguard your intellectual property. Ensure your play's title page features your name and the year of authorship, preceded by the copyright symbol: ©.

The realm of theater brims with inspiration, yet exercise caution to maintain originality in your narrative treatment. Plagiarism not only lacks integrity but also carries the risk of exposure.

A Model Outline for a Play Script

A Model Outline for a Play Script