1. Biological Characteristics

The average lifespan of a camel is 45 to 50 years. An adult camel stands at a height of 1.85m at the shoulder for a dromedary and 2.15m for a Bactrian. Camels can run at speeds of 65 km/h in areas with short shrubs and maintain speeds of up to 65 km/h. A Bactrian camel weighs between 300 and 1000 kg, while a dromedary weighs between 300 and 600 kg.

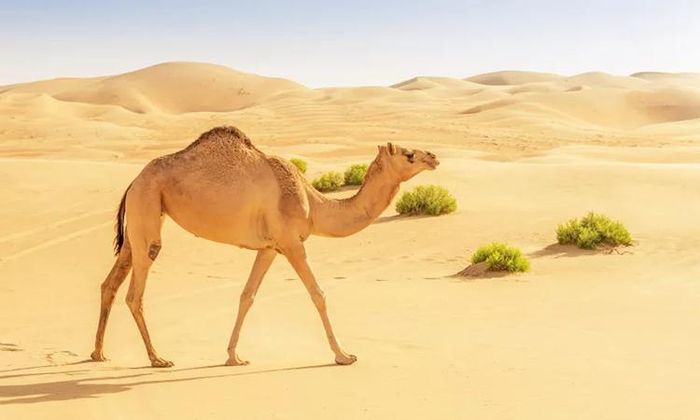

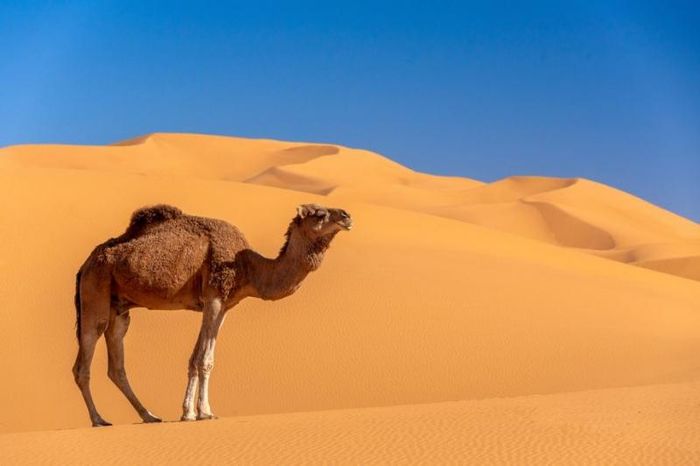

Camels endure the harsh conditions of the desert due to their protective coat against extreme heat and cold. Their large, flat feet with tough hooves help them navigate rough stone roads or soft sandy terrain. More importantly, they know how to conserve water within their bodies.

Camels don't sweat much and lose very little water through perspiration. Even the moisture in their noses is retained through a slit down to their mouths. Camels can walk for an extended period in the desert, during which their weight reduces by about 40%. However, their survival on the desert for extended periods is primarily due to their humps.

Camels are most famous for their humps, and these humps do not contain water as commonly believed. Instead, they store reserves of fatty tissue, while water is retained in their blood. This allows them to survive for many days without food and water. The camel's fat is utilized during food scarcity, causing the hump to shrink and become softer. Once water is available, the camel can drink large amounts to replenish lost fluids. Unlike other mammals, their red blood cells are oval, not round. This allows for better flow during dehydration, making them more resistant to high osmotic fluctuations without rupturing when consuming a large amount of water: a 600 kg (1,300 lb) camel can drink 200 L (53 US gal) of water in 3 minutes.

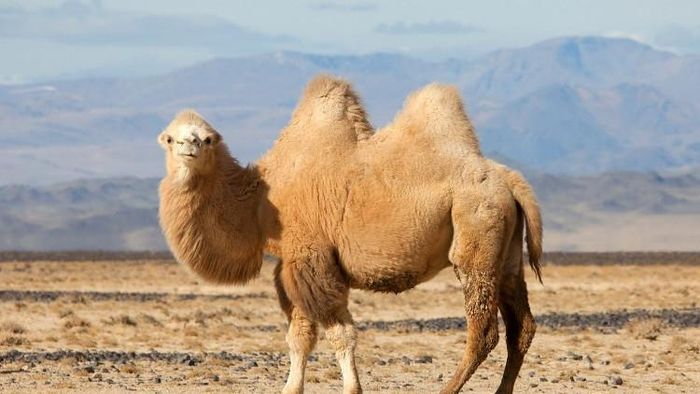

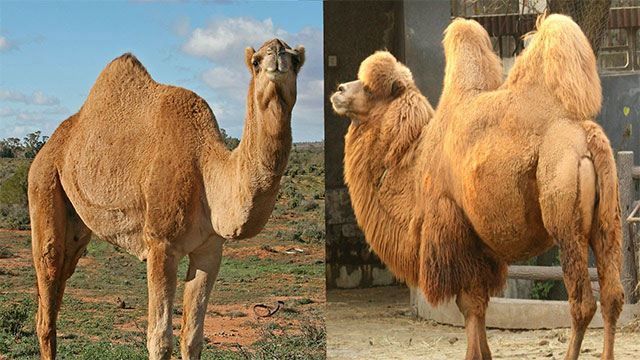

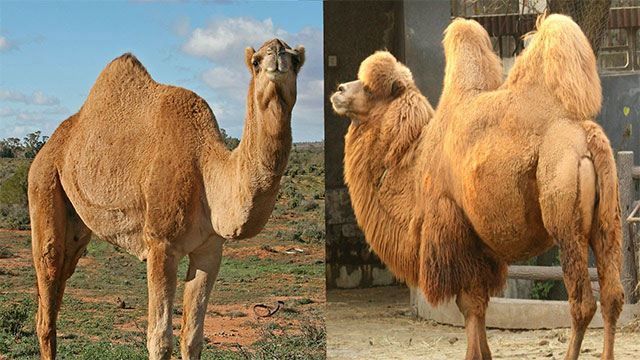

2. Camels are the Largest Animals Adapted to Desert Life

Camels, either one-humped (dromedary) or two-humped (Bactrian), are large even-toed ungulates in the Camelus genus. Both species originate from desert regions in Asia and North Africa. They stand out as the largest animals adapted to desert life, thriving in arid areas with scarce water resources.

The average lifespan of a camel ranges from 45 to 50 years. An adult camel, whether dromedary or Bactrian, stands at a height of 1.85m at the shoulder and can run at speeds of 65 km/h in regions with short shrubs, maintaining this speed effectively. Bactrian camels weigh between 300 and 1000 kg, while dromedaries weigh between 300 and 600 kg.

Humans domesticated camels around 5000 years ago. Both dromedary and Bactrian camels are utilized for their milk, meat, and as pack animals—the former in North Africa and Western Asia, and the latter in the eastern and northern regions of Central Asia.

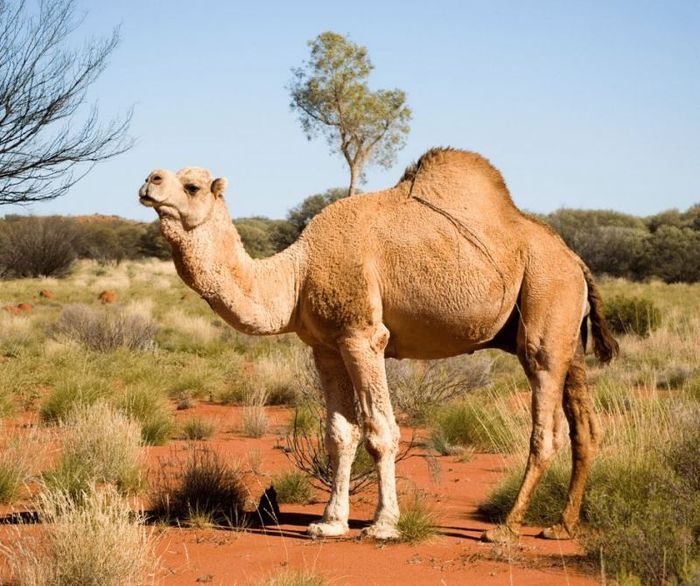

Although approximately 13 million dromedary camels still exist, they are domesticated, primarily in Sudan, Somalia, India, and nearby countries, as well as in South Africa, Namibia, and Botswana. However, there is a wild population of around 700,000 in central Australia, descendants of individuals that escaped captivity in the late 19th century. This population is growing at about 11% per year, prompting the South Australian government to decide to cull these animals due to their excessive consumption of limited natural resources on sheep farms.

3. Domestication of Camels

Bactrian camels have two layers of fur: a soft inner coat for insulation and a longer outer coat resembling hair. They produce approximately 2.3 kg (5 pounds) of wool annually. The structure of camel wool is similar to cashmere wool. The fibers are usually 2.5-7.5 cm (1-3 inches) long and are not easily separable. The wool is spun into threads for knitting.

Humans domesticated camels around 5000 years ago. Both one-humped (dromedary) and two-humped (Bactrian) camels are utilized for their milk, meat, and as pack animals—the former in North Africa and Western Asia, and the latter in the eastern and northern regions of Central Asia.

Although there are still around 13 million dromedary camels, they are domesticated, primarily in Sudan, Somalia, India, and nearby countries, as well as in South Africa, Namibia, and Botswana. However, a wild population of about 700,000 exists in central Australia, descendants of individuals that escaped captivity in the late 19th century. This population is growing at about 11% per year, prompting the South Australian government to decide to cull these animals due to their excessive consumption of limited natural resources on sheep farms.

Bactrian camels were once widespread, but their population has dwindled to around 1.4 million, mostly due to domestication. Approximately 1,000 wild Bactrian camels are believed to live in the Gobi Desert, with a small number in Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey, and Russia.

A small population of camels (both one and two-humped) was imported and lived in the southwestern United States until the early 20th century. These animals were imported from Turkey as part of the US Camel Corps experiment and were used as draft animals in mines. They either escaped or were released after the project ended.

4. Exceptional Abilities of Camels

The large mouth and nose of camels play a crucial role in water retention. The inner layer of a camel's nasal passage spirals, increasing the surface area for breathing. At night, this layer recovers water from exhaled air, simultaneously cooling the air, lowering it by 8.3°C compared to the body temperature. According to statistics, these unique abilities enable camels to save 70% of water loss in hot exhaled air compared to humans.

Camels typically start sweating only when their body temperature rises to 40.5°C. At night, camels often reduce their body temperature to below 34°C, lower than the daytime normal. On the second day, when they want to increase body temperature slightly to start sweating, it takes a very long time. Thus, camels rarely sweat and urinate, conserving water in their bodies.

Most people die of thirst in the desert due to the loss of water in their blood, making the blood dense. The heat in their bodies is challenging to dissipate, leading to a sudden increase in body temperature and death. In contrast, camels can maintain blood volume even when dehydrated. It seems that only after all the camel's body fluids are lost does it lose water in the blood.

Interestingly, camels can both 'conserve water' and 'exploit water.' A camel's stomach is divided into three compartments, and the two front compartments have many 'water pouches' that store water for droughts. When they find water, they not only store it in the 'water pouches' but can also quickly transfer water into the blood reservoir for later use.

Camels, trekking long distances across the desert, need to store sufficient energy. The fat reserve in their hump is equivalent to 1/5 of their body weight. When they cannot find food, they can rely on the fat in these humps to sustain life. Additionally, during the oxidation of fat, water can be generated, supporting the maintenance of the necessary water for life activities. Therefore, camels can be described as both a 'food reserve' and a 'water reserve.'

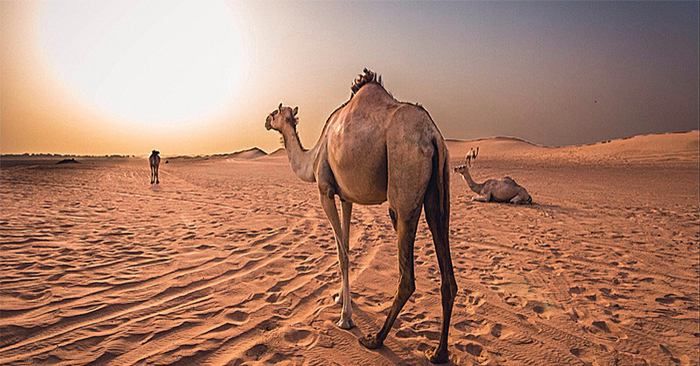

5. Camel - The Most Resilient Desert Survivor

Amongst the animal kingdom, camels stand out as the most resilient creatures. A single camel can carry up to 200 kg of cargo, trek 40 km daily, and endure continuous travel for 3 days in the desert. If not walking, they can run at 15 km/h for 8 hours without a break. Hence, the title 'ship of the desert' truly befits them.

While traversing the desert, they often face daunting situations such as sandstorms from all directions, swirling golden sands obscuring vision, and the world spinning around them. In such instances, camels calmly lie down, shut their eyes, and their long, thick eyelashes act as a wind-blocking curtain, safeguarding their eyes. Once the sandstorm passes, they rise, shake off the sand, and quietly resume moving forward.

In the scorching summer, with the sun blazing like fire and desert temperatures soaring above 50°C, walking on the desert feels like walking on hot coals, each step challenging. Yet, camels pay no heed. Their large, sturdy feet traverse the desert as if walking on a flat surface, unwavering and not sinking. Moreover, beneath their feet, there's a thick horned cushion, resembling a special 'boot,' completely unfazed by the heat.

The greatest endurance of camels is enduring relentless hardships in the desert, sometimes up to 10 days or half a month without water. It turns out, in times of drought, camels possess unique physiological functions to resist water loss.

Camels withstand the harsh desert conditions because of their shaggy fur protecting them from extreme temperatures during sunny days or nights in the desert. Their feet, equipped with large, sharp hooves, allow them to tread steadily on rocky paths or soft sand. More importantly, they know how to retain water in their bodies.

6. Hump - The Energy Storage of Camels

Camels store energy in their humps for times when food sources become scarce. Whenever a desert becomes barren or a harsh winter kills off vegetation in sandy lands, its only hope lies in the fat reserves stored in its hump.

Many believe a camel's hump is a water reservoir helping it traverse hundreds of scorching desert kilometers. That's entirely false. The hump doesn't contain water but accumulates the fat the animal gathers from eating grass. 80% of its mass is dense fat.

Devoid of water, the hump is, in fact, an energy storage facility. Precisely, that white mass consists of 2/3 saturated fatty acids, with a melting point above 80°C. Thus, even under the blazing sun, the hump remains intact. Conversely, when the camel metabolizes that energy reserve, its skin contracts, and the hump deflates.

The hump varies based on nutritional conditions, weighing from 1 kg to 90 kg for an animal ranging from 300 kg to 800 kg. It's a delicacy shared among nomads when a camel dies, used for cooking stews, and even employed for medicinal fumigation. In emergencies, lost and starving camel herders might cut a piece of a camel's hump for temporary sustenance. Subsequently, the animal's wound quickly heals.

Camels endure thirst for up to thirty days in scorching deserts, not due to their humps but owing to a unique physiological mechanism and anatomy. In reality, the hump's metabolism slows down as the heat rises from 34 to 42 degrees.

7. How Camels Retain Water in Their Bodies

Camels adapt to desert life due to their bushy coats, shielding them from extreme temperatures under the desert sun or during chilly nights. Second, their feet boast large, sturdy cushioned pads, allowing them to tread confidently on rugged rocky paths or soft sandy terrains. They walk on the thick pad of their foot's sole, not on their hooves, preventing sinking into soft sand. More importantly, they know how to retain water in their bodies. They urinate infrequently and allow body temperature to rise, indirectly reducing water loss.

Camels don't sweat much and lose minimal water through excretion. Even nasal fluids are retained through a slit down to the mouth. They only sweat when excessively hot. The nostrils can close not only to prevent sand but also to inhibit water evaporation during breathing. The humps store ample energy-rich fat, enabling them to endure weeks of hunger in the desert. Camels can walk for an extended period in the desert, during which their weight decreases by about 40%. However, their sustained survival in the desert is primarily thanks to their humps.

Water is stored in their blood, allowing them to survive for several days without drinking. Camel fat is utilized during food scarcity. The hump then contracts and softens. When water becomes available, it can drink up to 57 liters in one go to replenish lost fluids.

8. Why is it Forbidden to Touch a Dead Camel in the Desert?

If you have outdoor survival knowledge, you'll know that, except for camels, the carcasses of many animals are not easily approachable due to the potentially dangerous consequences. Travelers stranded in the desert, extremely hungry, might attempt to obtain meat and water from a dead camel, but if you see a swollen carcass, beware.

After a camel dies, a large number of bacteria will proliferate in the flesh. Even if preserved with water, it remains inedible. Furthermore, scavengers and cadaverine can breed bacteria causing diseases like Salmonella, and human infection can lead to poisoning.

On the other hand, a dead camel's body can explode. The fat in the camel's hump, after death in the desert, transforms into organic acids, methane, and carbon dioxide in the low-oxygen environment; proteins decompose to produce gases like ammonia and hydrogen sulfide. Decay is faster in desert areas exposed to sunlight and high temperatures. Consequently, gases in its body rapidly expand, causing the dead body to swell into a bloated 'balloon.'

At this point, a slight disturbance could trigger the camel's body to explode. Careless human approach could lead to disaster. Some scientists describe a dead camel's body as a 'biological weapon.' You might wonder: Can the explosion of an animal carcass be that powerful? In reality, similar incidents have occurred before, such as the explosion of a whale carcass. The explosion of a dead camel may not be as intense as a whale, but it should not be underestimated. After the explosion, those nearby may be hit by blood and airwaves, causing injuries and making them vulnerable to bacterial attacks. Therefore, if you encounter a dead camel in the wild, it's best not to approach it.

9. Camel's Hump Aids in Regulating Body Temperature

Have you ever experienced a night in the desert? If not, you might not be aware of how the desert temperature fluctuates. It gets scorching hot during the day and bone-chilling cold at night, a result of the properties of sand. However, the fat tissues in a camel's hump act as insulation to combat such extreme temperature variations.

There are two types of camels: the Bactrian camel, found in West Central China and Central Asia, typically having two humps, and the Arabian camel, more common with only one hump, known as the Dromedary. Unfortunately, there's no scientific evidence explaining why Bactrian camels have two humps. Some loose conjectures suggest they developed two humps due to harsher living conditions.

For instance, Bactrian camels primarily inhabit the Gobi Desert, known for its harsh environment. The desert features an unusually cold climate, with temperatures dropping to -40 Fahrenheit (-40 degrees Celsius). While many animals store fat around their abdomen and sides, camels uniquely do so vertically. One hypothesis suggests that storing fat in humps rather than around the sides helps camels minimize exposure to sunlight and lower temperatures.

As Bactrian camels store food in their humps, they need alternative ways to cope with water scarcity. For instance, they can drink up to 30 gallons (114 liters) of water in a single sitting, excrete dry feces to conserve water, and efficiently filter toxins from their urine to retain as much water as possible. Camels also have other methods to move long distances, such as extracting moisture from every breath they take.

10. Camel's Milk and Urine Can Potentially Cure Cancer

A group of researchers from the Arab Biotech Company (ABC) has recently announced the successful development of a medicine comprising compounds extracted from camel's milk and urine to treat cancer. The researchers believe that the camel's immune system is one of the most robust. Therefore, the new medicine contains highly vital camel cells that will target and eliminate toxic substances in cancer cells without causing adverse effects.

The research team asserts that experiments on mice have shown a 100% success rate. After six months of administering the new drug, experimental mice with cancerous tumors continued to live and function normally, comparable to other healthy mice.

Dr. Abdalla Al-Naja, President of the Arab Science and Technology Foundation (ASTF), stated that the new medicine, a combination of camel's milk and urine, has the potential to treat various types of cancer, such as leukemia, lung, liver, and breast cancer. The drug has demonstrated positive results in mouse trials and is poised for human testing in the near future.

Worldwide, approximately 6 million people die from cancer each year, ranking it as the second leading cause of death in the Arab world, following cardiovascular diseases.

11. Luxury Fabric Made from the Rare Wool of Camels

Fabric made from the wool of this camel species is even more precious than Cashmere goat wool, which is already very expensive. The Vicuña camel, in comparison to common camels, is exceptionally charming and elegant. Notably, its wool can be woven into fabric like sheep's wool. Furthermore, this fabric is extremely rare. Even today, it remains more expensive than other high-quality fabrics, at least five times over.

If you're wondering why this animal is so highly valued, the reason lies in its wool. Vicuña wool is harvested from the rarest animal on the brink of extinction, making it the most expensive wool in the world. The Andes mountain peaks are known for their harsh conditions, poor nutrients, and extreme temperature fluctuations, ranging from warm during the day to freezing at night. The Vicuña's existence in this region is considered a miracle, partly due to its precious wool.

During the Inca Empire, the Vicuña camel was revered as a sacred animal. It was prohibited to kill them, and their wool was used exclusively to make clothing for the royalty. Despite its delicate appearance, the Vicuña camel is not a fragile species. Adapted to high altitudes in the harsh Andes, it develops an enormous amount of red blood cells to enhance oxygen utilization.

The digestive system of the Vicuña camel is as robust as a machine. It can grind tough, dry grass with ease. However, the most notable feature is the Vicuña's wool. It consists of soft, fine fibers with extremely high insulation properties. While most woolen products exhibit static electricity, Vicuña camel wool does not. Each fiber is only 12-14 microns thick, compared to Cashmere goat wool at around 19 microns and sheep wool at about 25 microns.

In the textile industry, the finer the natural fiber, the more valuable it is. Additionally, Vicuña camel wool grows extremely slowly, making it even more precious. In short, this 'golden wool' is five times more expensive than Cashmere goat wool.

12. How Do Camels Forage for Food in the Desert?

The flexibility of their lips allows camels to graze on low-lying grass and thorny plants to survive in the harsh desert. All three camel species - Camelus dromedarius, Camelus bactrianus, and Camelus ferus - have evolved to live in the desert. In addition to one or two humps on their back filled with nutrient-rich fat, acting as an energy reserve, they also have specialized lips to maximize scarce food sources in the challenging environment.

The split upper lip of the camel is movable, with each half capable of independent movement, enabling the animal to graze on short grass close to the ground, crucial in the slow-growing desert. Camel lips are tough but still flexible, allowing them to break and eat even spiky vegetation. Moreover, the inside of their mouths has cushion-like papillae that act as a lining to prevent sharp thorns from poking through, aiding camels in chewing and swallowing food more easily, according to the Natural History Museum in London.

In general, camels eat grass, leaves, and branches from any desert plant, including dry grass and salt-tolerant shrubs. What happens after they swallow the food? The camel's stomach has three to four compartments. The food is partially broken down in the first two compartments before regurgitating to chew again. In the second swallowing, the food goes into one or two remaining stomach compartments, where it is digested by bacteria.

Another remarkable ability is that camels can survive over a week without water and can go for a month without grazing, allowing them to wander for days with an empty stomach in search of food, according to PBS.

13. Camels Can Drink 113 Liters of Water in Just 13 Minutes.

When camels need to hydrate before long journeys, an adult camel can drink up to 113 liters of water in just 13 minutes. Moreover, camels possess a body that rehydrates faster than any other mammal on the planet. Unlike other mammals, their red blood cells are oval-shaped, not circular.

Camels carry many unique evolutionary features to thrive in harsh environments like the desert. For example, camels have three eyelids and two sets of eyelashes to prevent dust and sand. They have a pair of lips and an extremely thick oral palate, allowing them to effectively 'cup' long, sharp plants that almost no other animals can consume. Large, flat feet help camels avoid sinking into the sand and provide stability. This species can even open and close their nostrils flexibly to avoid dust.

More than just riding animals or pack carriers, camels play a crucial role as a food source for humans in the form of meat and milk for thousands of years. Camel milk is highly nutritious, containing ten times the amount of iron and three times the amount of vitamin C compared to cow's milk. Notably, camel milk has a structure and nutritional composition closer to human breast milk than any other type. It also contains less lactose than any other milk, making it suitable for those who are lactose intolerant to consume normally.

14. Vicuña Camel: Icon of Peru

In ancient times, only the Inca nobility (a red-skinned people in southern America) were allowed to wear Vicuña camel wool. It was so precious that it was called the 'golden fleece.' The Vicuña camel, scientifically known as Vicugna vicugna, only lives in the high mountains of the Andes. It has a small body, innocent large eyes like a deer, and golden fur. At first glance, the Vicuña camel is extremely graceful and elegant.

In Peru, the country that hosts the habitat of the Vicuña camel in the Andes region, this species is considered a national symbol. Its image is printed on the national flag, emblem, and coins. Currently, Peru has about 2 million Vicuña camels. During the Inca Empire, the Vicuña camel was also considered a sacred animal. Killing it was prohibited, and its wool was only used to weave clothing for the royal family.

Despite its graceful appearance, the Vicuña camel is not a weak species. Living in the harsh Andes mountains, it develops a large number of red blood cells to enhance oxygen utilization. The digestive system of the Vicuña camel is as robust as a machine. It can crush dry and tough grass effortlessly. Notably, the fur of the Vicuña camel includes soft, fine fibers with extremely high insulation properties.

We all know that most wool products have static electricity properties, but not Vicuña camel wool. Each fiber is only 12-14 microns thick, while Cashmere goat wool is around 19 microns, and sheep's wool is about 25 microns.

In the textile industry, the thinner natural fibers are, the more valuable they become. Additionally, Vicuña camel wool grows extremely slowly, making it even rarer. This 'golden fleece' is more expensive than Cashmere goat wool by five times. Let's compare the aesthetic impact by looking at Cashmere, one of the famous wools taken from goats living in the Himalayas.