(Homeland) - A recent study has elucidated the phenomenon of why the water suddenly turns red at the Blood Falls in Antarctica.

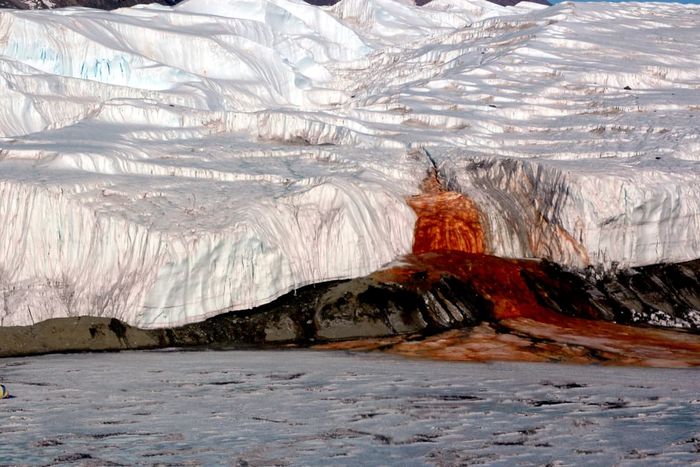

A vibrant red waterfall is not something you'd expect to see in the icy landscape of Antarctica, but that's precisely what's flowing from the base of the Taylor Glacier.

This peculiar and somewhat eerie sight was first discovered in 1911 by geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor, who attributed the phenomenon to red algae.

Half a century later, this deep crimson color was identified to be caused by iron salts. Interestingly, this phenomenon is also highly intriguing as the water initially appears clear but turns red upon contact with air for the first time in millennia due to iron oxidation.

Now, a recent study has examined water samples and discovered that iron appears in an unexpected form. Technically, it's not a mineral – instead, it takes the shape of nanospheres, smaller than 100 times the size of human red blood cells.

'Upon examining the microscopic images, I noticed these tiny nanotubes that are rich in iron, as well as various other elements inside the iron - silicon, calcium, aluminum, sodium - and they're all diverse,' stated Ken Livi, a researcher.

'To become a mineral, atoms must be arranged into a very specific crystalline structure. These nanospheres are not crystals, so the methods previously used to test solids did not detect them.'

Significantly, this latest discovery extends beyond Antarctica and even beyond Earth.

Just a few years ago, scientists sought to trace the origin of water at Blood Falls - a subglacial lake under extremely salty, high-pressure, lightless, and oxygen-free conditions, with a microbial ecosystem isolated for millions of years.

This suggests that life may exist on other planets in similar harsh conditions, but we may not be sending the right kind of equipment to detect it.

'Our research reveals that analyses conducted by rovers are insufficient in determining the true nature of environmental materials on the surface of other planets,' Mr. Livi stated.

'This holds especially true for colder planets like Mars, where the forming materials may exist in nano sizes and remain non-crystalline. To truly understand the nature of the rocky planet surfaces, an electron microscope is necessary, but currently deploying such a device on Mars is impractical.'

Reference: News Atlas