1. The Tradition of First-Footing on New Year's Day

2. New Year's Greetings

3. Giving Lucky Money at the Start of the Year

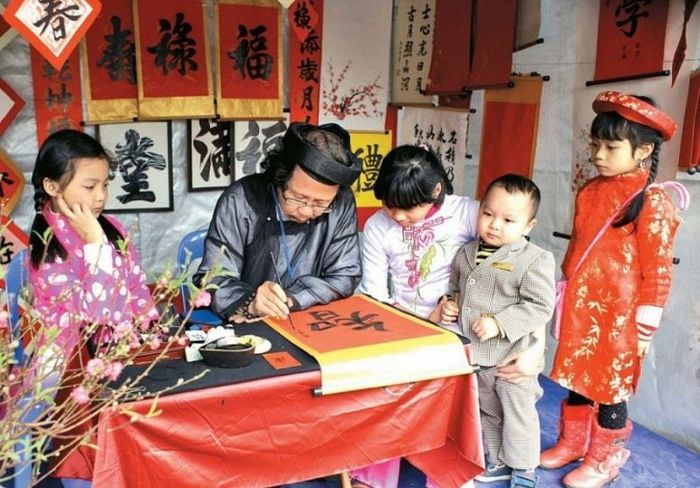

4. New Year's Calligraphy

5. Enjoying Flowers During the Lunar New Year

6. Making Bánh Chưng and Bánh Tét

In the days leading up to the New Year, children far from home eagerly finish their work, hoping to return to their families and partake in the tradition of making Bánh Chưng together. In the past, homes would begin preparing the ingredients for the cakes 2 or 3 days before Tết, and on the eve of the New Year, families would gather outdoors, washing leaves, sorting beans, and preparing meat for the wrapping. But perhaps the most joyous part of the process was cooking the cakes and waiting for them to finish. Despite the chilly air outside, the warmth of the family gathered around the fire made the moment feel truly festive. The Bánh Chưng cakes, beautifully wrapped and square, would be placed on the family altar to honor ancestors, while smaller cakes were set aside as treats for the children as a New Year’s gift.

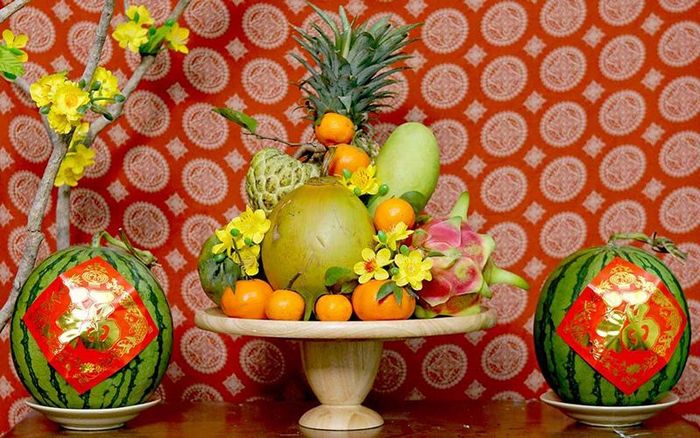

7. Arranging the Five-Element Fruit Tray

Due to the diverse geography of Vietnam, the presentation of the Five-Element Fruit Tray can vary by region. The traditional arrangement often places a banana bunch at the base to support the other fruits. In the center, a round grapefruit or a beautifully colored Buddha's hand sits as a focal point. Smaller fruits such as oranges, tangerines, and pomegranates are arranged around the larger ones. The careful arrangement of colors and sizes creates a visually pleasing and auspicious display. While the Southern and Northern regions have their own distinct fruit selections, the Central region blends elements from both. A variety of fruits such as bananas, grapefruits, mangoes, watermelons, oranges, apples, grapes, figs, pineapples, and soursop are commonly used.

8. Ancestor Worship Ceremony

Particularly during the Tết feast for ancestors, the preparation and presentation of the offerings are done with great care. Depending on the family's economic situation, the size of the offerings may vary, but the essential components are always the same: Bánh chưng (square sticky rice cake), pork, pickled onions, and white rice. The Bánh chưng symbolizes fertility and the cycle of life, representing the growth of all living things with each passing year. The pork represents yin, the pickled onions symbolize yang, and their balance reflects harmony and development. The rice, an essential food source, is represented by both glutinous and non-glutinous rice, showing the completeness of life with both yin and yang. The dipping sauce, placed at the center of the round tray, with four bowls of rice arranged at the corners, represents the universe—illustrating the interconnectedness of all beings, both in the physical and spiritual worlds.

9. Midnight Rituals for the New Year

The Midnight Offering is made outdoors, where a small altar is set up with incense burning brightly. Two oil lamps or candles are placed on either side. Traditionally, the altar offerings include a plate of red sticky rice (xôi gấc) symbolizing luck, a well-cooked rooster with a red rose in its beak representing health and purity, and commonly bánh chưng or bánh tét, along with sweets, betel leaves, fruits, wine, and water. It's crucial not to forget the wine, as "without wine, no ritual is complete." The incense is placed in a small bowl of rice or a jar to hold it upright. Some families may simplify the ritual by placing the incense directly on the altar or in the folds of banana leaves. The ritual also signifies a fresh start, casting away the misfortunes of the old year and embracing the prosperity and good fortune of the new year. Once the ceremony is complete, the family comes together to celebrate the arrival of the New Year.

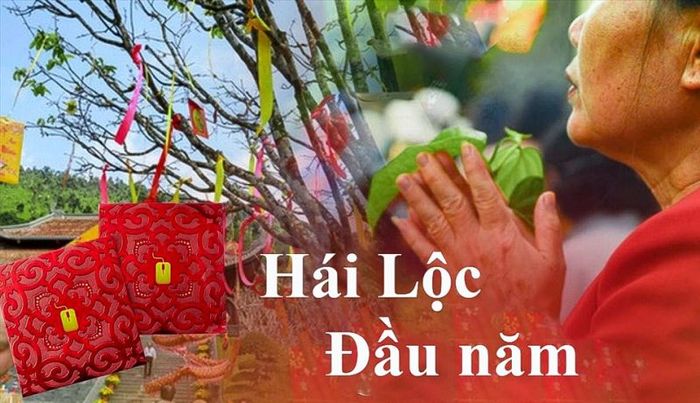

10. First Blessings Picking

The tradition of picking the first blessings of the year is a ritual where people cut branches (known as 'lộc') from trees and bring them home to invite good luck. This occurs during the early days of the Lunar New Year. These branches often come from trees like banyan, fig, or areca, which are known for their perennial vitality and ability to sprout new growth. The 'lộc' refers to the first bud or sprout of the season. The branches are displayed in the home, often placed at the entrance or in vases, symbolizing the removal of negative energy and the welcoming of good fortune. During Tết, it's common for people to visit temples to pick these branches, believing that the sacred spaces will provide divine blessings for the year ahead.

This tradition has been passed down for thousands of years, especially in the area of ancient Văn Lang. The practice of seeking blessings at the start of the year has become an integral part of Tết celebrations in Vietnamese culture. People believe that by picking these branches from temples, they invite spiritual protection and prosperity for the coming year. These branches, typically small and from strong, resilient trees, are displayed at the home as a symbol of good health, fortune, and spiritual strength.

11. The Tradition of Setting Off for the New Year

At the start of the new year, the Vietnamese observe a custom known as setting off. This involves leaving the home on the first day of the year in search of good fortune for oneself and the family. Before embarking on this journey, one must carefully select the right day, time, and direction to encounter benevolent spirits and bring prosperity. Traditionally, people travel to temples, shrines, or visit elders, relatives, and friends to offer New Year’s greetings. For farmers in the past, the first day’s journey also served as a way to observe the weather and make predictions for the year ahead. As the sun rises, people would leave their homes to check the direction of the wind, using it to gauge whether the coming year would be fortunate or challenging. If they visit a temple or shrine, it is customary to pick a 'lộc branch' as a symbol of good luck and blessings. This branch, often from trees like banyan, fig, or cactus, is known for its vitality and new growth.

The tradition of picking 'lộc' at temples symbolizes receiving blessings from the deities and spirits for the year ahead. The lộc branch is often placed on the ancestral altar at home. The ancient belief is that when setting off, one should leave during an auspicious time, preferably when it aligns with the person’s astrological compatibility. People hope that by following this tradition, the year will start with good fortune. After setting off, they typically visit relatives and friends, strengthening bonds and wishing well for the whole family. Another important custom is that during the first three days of the new year, regardless of where one may go, they must return home by evening. This practice symbolizes the importance of coming back to family and preventing bad luck from lingering.

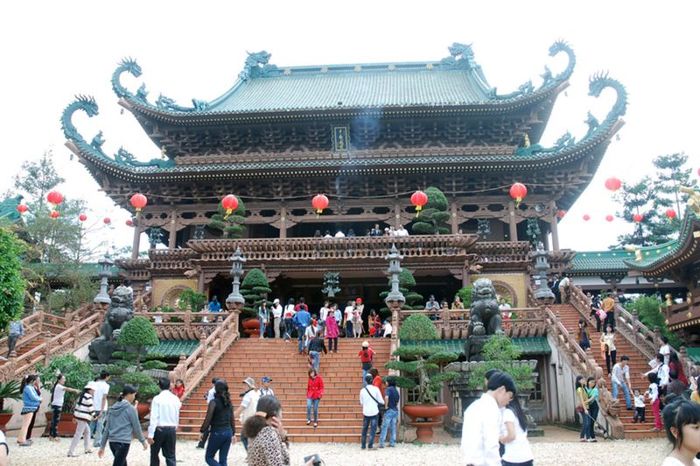

12. New Year's Temple Visit

For generations, the Vietnamese have viewed Tết not only as a celebration to bid farewell to the old year and welcome the new one but also as a deeply spiritual and cultural time. Beyond honoring ancestors, it is customary for people to visit temples and shrines to pray for blessings and good fortune for their families, hoping for the best in the year ahead. Right after the stroke of midnight, marking the transition from the old to the new year, many people flock to local temples to pray for peace, wealth, and prosperity. It has become a yearly tradition—after paying respects to their ancestors, families head to the temple to light incense and make offerings for the new year.

The temple, a sacred and serene place, offers an escape from the busyness and worries of everyday life. Seeking inner peace and letting go of the burdens of the past year, people visit temples after the clock strikes twelve on New Year’s Eve or in the early moments of the new year to pray for good luck. New Year’s temple visits are an integral part of Vietnamese spiritual culture. It’s believed that such visits are not only to make wishes but also serve as a chance to reconnect with the spiritual world and find tranquility in the midst of life’s struggles. In the quiet of the temple, surrounded by incense smoke and the glow of lanterns, we often feel a sense of calm and renewal.

13. Sending Off the Kitchen Gods to Heaven

Every year, on the 23rd day of the 12th lunar month, the people of Vietnam prepare offerings to send the Kitchen Gods back to heaven. This is a unique and cherished tradition that has been passed down through generations. The ritual honors the Kitchen Gods, who have been a part of Vietnamese culture for centuries. According to legend, Ông Công is the guardian of the household and the land, while Ông Táo, the three Kitchen Gods, oversee the cooking and kitchen duties. These gods are believed to descend to Earth to observe the deeds of the household, recording the good and bad actions of the people.

On the 23rd day of the 12th lunar month each year, these gods return to the heavens riding carps to report to the Jade Emperor on the behavior of the people throughout the year, determining their fate for the coming year. In Vietnamese belief, Ông Công and the three Kitchen Gods (or the Kitchen Kings) are responsible for bringing prosperity, good fortune, and blessings to the family. Naturally, the family’s prosperity is tied to the moral conduct of its members. With the hope of ensuring good fortune for the year ahead, families perform the ritual of sending the Kitchen Gods back to heaven in a grand and respectful ceremony.

14. The Tradition of Visiting Ancestor Graves Before Tết

Every year, from the 20th to the 30th day of the lunar year, Vietnamese families carry out the ritual of visiting ancestor graves. In the belief of the people, when the New Year arrives, everything must be renewed, including honoring the deceased. Visiting the graves of ancestors is an important part of Vietnam’s cultural tradition, deeply rooted in the practice of ancestor worship, a custom that has been passed down for generations. Many families view this ritual as an opportunity to share the events of the past year with their ancestors and to respectfully invite them to join the family for the New Year celebration.

Following this tradition, there is also a custom of bringing ancestors' spirits back to the household on the afternoon of the 30th lunar day and sending them off again, usually on the 3rd or 4th day of the New Year, depending on regional customs and family traditions. The farewell ceremony often coincides with the end of the festive days of Tết, when everyone returns to their normal routine. This act of returning to daily life carries with it the belief that the ancestors' blessings will guide and protect the family in the year ahead. The tradition of visiting ancestor graves before Tết has long been a part of Vietnam's spiritual life, demonstrating filial piety and respect for those who came before.

15. Year-End Feast

To close the year and prepare for the upcoming one, Vietnamese families often host a year-end meal, an essential tradition in Vietnamese Lunar New Year celebrations, typically held on the 30th day of the lunar month (or the 29th if the month is short). This event isn't just about family members gathering for a meal; it has become an opportunity for friends to meet and celebrate together as they usher in the New Year. Thus, the year-end meal is an unmissable tradition for the Vietnamese people.

The year-end feast serves as a moment for families to reflect on the year's accomplishments, address any shortcomings, and set new goals for the coming year. It is a joyful and lively gathering, filled with wishes for success and growth in the past year, while also preparing to welcome a better year ahead.