In 1997, a 46-year-old man sued the local police department after being refused a job for scoring too high on an IQ test. Strangely, the court sided with law enforcement.

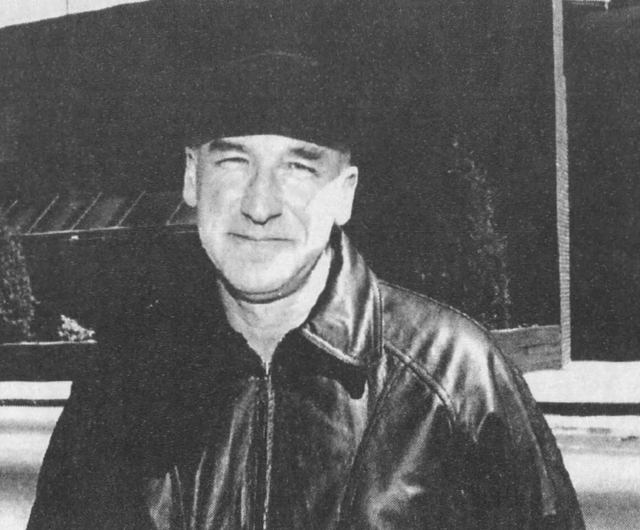

In 1997, Robert Jordan applied for a patrol officer position at the New London Police Department in Connecticut, USA. He took an intelligence test called the 'Wonderlic Personnel Test' and an academic test administered by the Southeastern Connecticut Council of Governments. Jordan scored 33 points, compared to the average of 21 for other candidates.

Despite his high score, the city police department 'forgot' to hire Jordan. He believed his chance was lost because of his age, 46 at the time, which was considered relatively old for the job, especially compared to younger applicants. However, Jordan was not satisfied and filed a lawsuit with the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities. That's when he realized the real issue was the intelligence test results.

Keith Harrigan, the City's Assistant Director at the time overseeing recruitment, told Jordan: 'We don't like to hire people with high IQs to be cops in this city.'

Jordan's reaction was simply one of astonishment: 'Philosophically, I find it derogatory to the entire law enforcement profession.'

However, the logic employed by the police department in their recruitment process is very clear: Any candidate who scores too high on the IQ test will sooner or later become disillusioned with the job in the police force and will leave, sooner or later. In fact, the city of New London estimates that they have spent $25,000 to train each new police recruit, so they cannot afford to train candidates who will quit the police job shortly after starting.

'I just couldn't accept it. And I found out there was absolutely no evidence. There's no correlation between your basic intelligence and job satisfaction or long-term work time,' Jordan said. 'What message does that send to children? Study hard, but don't be too good?'

And so, he went to court and accused the city government and the New London police department of violating his equal protection rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the county court upheld the police department's defense: 'There is a legitimate reason for the police department to require a not overly intelligent police officer.'

Jordan appealed the ruling, but in 2000, the Second Federal Appellate Court in New York upheld the decision of the Connecticut county court, and Jordan was once again defeated. The appellate court ruled that 'the same criteria are applied to all test takers, so Mr. Jordan's Fourteenth Amendment rights were not violated.'

Most disappointing to Jordan was the court's determination of right and wrong based on the test provider's documentation. And this was explained in the court's decision against his appeal: 'We conclude that even if no statistically significant correlation has been conclusively demonstrated between high test scores and job dissatisfaction, it is enough for the city to trust - based on documentation provided by the test provider - that there is such a relationship. The plaintiff has provided some evidence that those who score high do not actually feel more dissatisfied in their jobs, but that evidence does not pose a practical problem.'

In other words, all that matters is that the city government 'believes' the entrance exam was conducted correctly. As long as that belief is applied equally to all applicants, no constitutional right is infringed.

Fortunately for Jordan, despite failing to secure a position in the police department, he managed to find a new job at the Rehabilitation Department. This indicates that at least he wasn't overly intelligent to become a prison warden.

But there was a stroke of luck for Jordan. After failing to qualify for the police force, he was still able to land a new job at the Rehabilitation Bureau. This proves that he wasn't too clever to become a prison guard, at the very least.

Reference Gigazine