1. !Xóõ: Botswana

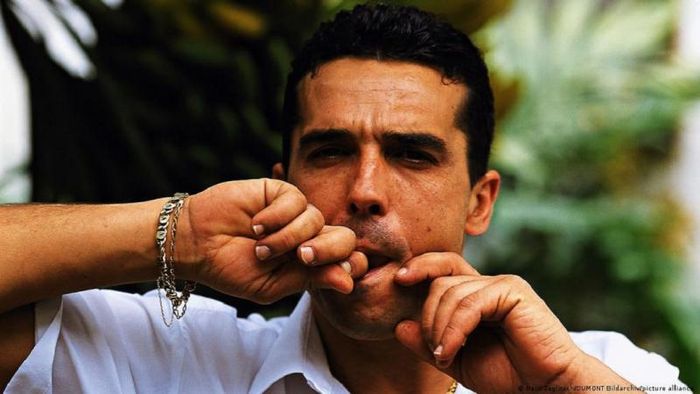

The language !Xóõ, also known as Taa, spoken in Botswana, is one of the so-called 'click languages' found in Southern Africa. For foreign ears, it sounds quite unusual. While Rotokas is considered one of the simplest languages, !Xóõ stands as one of the most complex. It has over 160 distinct phonemes, 110 of which are produced using click sounds. These clicks can also vary in tone: low, mid, and high. Mastering these clicks can be particularly challenging for non-native speakers.

What makes !Xóõ unique is its "explosive array of unusual sounds," which contribute to its classification as one of the world's most intricate spoken languages. For instance, Tony Trail, a leading expert in !Xóõ (but not a native speaker), developed a vocal cord tumor while trying to master the "five basic clicks and 17 associated clicks," along with four different vowel types (each with four distinct sounds). Later, he discovered that native speakers of !Xóõ tend to develop a similar condition as well.

2. Rotokas: Papua New Guinea

Rotokas is one of 830 languages spoken in Papua New Guinea. It is a language from the North Bougainville group, spoken by around 4,000 people on the island of Bougainville. With only 12 phonemes and a 12-letter alphabet, Rotokas is known as one of the simplest languages in the world. It also lacks nasal sounds. This language is quite unique because it doesn't use nasal consonants, except when a native speaker mimics the attempts of foreigners trying to speak Rotokas.

There are three main dialects of Rotokas: Central Rotokas, Aita Rotokas, and Pipipai. The Central Rotokas dialect has one of the smallest phonetic inventories in the world, possibly the smallest modern alphabet. Its alphabet includes twelve letters that represent eleven phonemes. Rotokas distinguishes between short and long vowels, but it does not have features like tonal contrasts or stress accent that are found in many other languages.

3. Guugu Yimithirr: Australia

Guugu Yimithirr is an Australian Indigenous language that contributed the word 'kangaroo' to the English language. It is a Pama-Nyungan language primarily spoken in Hopevale and Cooktown in Far North Queensland, which is located in the northern part of the Australian state of Queensland. As of the 2016 census, around 780 people speak Guugu Yimithirr. While most of the speakers are adults, there is a growing number of younger people who can speak it as well. Various community groups are actively working to revive the language.

Other common spellings of the language include Guugu Yimithirr, Gugu Yimijir, Gugu-Yimithirr, Guguyimidjir, Guugu Yimithirr, Koko Imudji, and Kukuyimidi. The native name of the language, Guugu Yimithirr, translates to "this speech." Guugu Yimithirr was first recorded in 1770 by Lieutenant James Cook (later Captain Cook), Joseph Banks, and Sydney Parkinson. It is considered the first written Indigenous language of Australia. They collected various words from Guugu Yimithirr, including the term for 'kangaroo,' which was used to describe a large black or gray kangaroo and often written as 'gangurru.'

4. Silbo Gomero: La Gomera, Spain

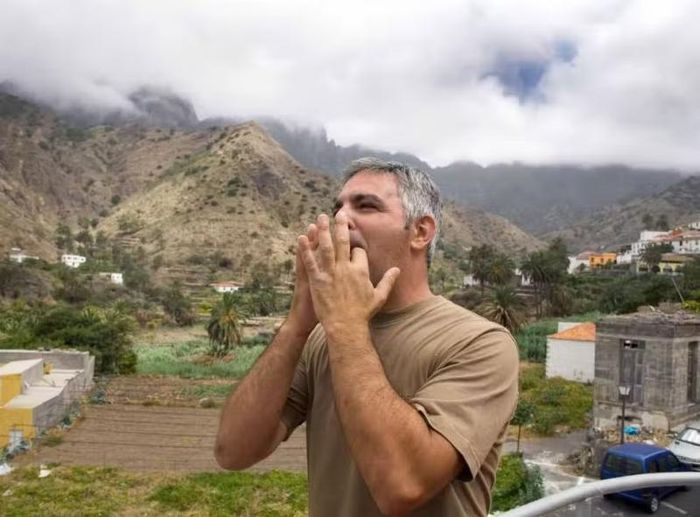

Silbo Gomero is a unique language spoken on the coast of Spain. It is entirely composed of whistling sounds and has been in use since the 15th century on La Gomera, one of the smallest islands in the Canary Islands off the northwest coast of Africa. The whistling language was originally developed to help people communicate across challenging landscapes like ravines and valleys, where regular speech could not carry over.

What may sound unusual to outsiders, these whistles are varied in pitch and tone. The variation is achieved by shaping the hands to create something that closely mimics spoken language. Although this may seem odd to non-natives, it is an incredibly effective form of communication. The indigenous North African settlers who first inhabited the island used whistled language, and the first European settlers adopted it as well. Today, performances of Silbo Gomero attract many tourists, and the language is also taught in local schools.

5. Archi: Dagestan, Russia

Archi is a language spoken in Dagestan, Russia, by about 900 people in 8 villages near the Risor River in Dagestan. With such a small number of speakers, the language is currently at risk of extinction. While its small-speaking community certainly adds to its uniqueness, what truly makes it stand out on this list of unusual languages is not just its rarity.

In Archi, a single verb can have up to 1.5 million different forms. Yes, you read that correctly: 1.5 million verb forms. For example, take the verb “to swim.” In English, we have variations like “I swim,” “he swims,” and “they swim,” along with tenses like “I swam” or “I will swim,” which already complicate things. Now, imagine all of these versions, but multiplied by 1.5 million different combinations. Factors such as tense, mood, evidentiality (how the speaker knows what’s happening), and many other variables contribute to the staggering number of verb forms in this language.

6. Esperanto

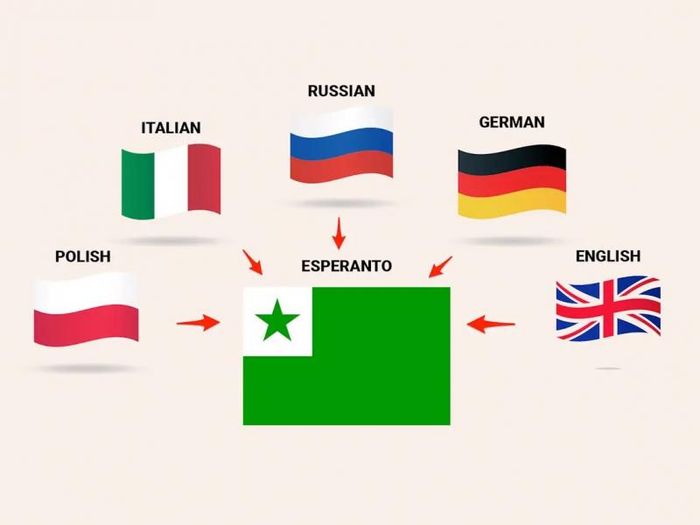

Esperanto is a unique constructed language that boasts over 2 million speakers worldwide. It was created in 1887 by Dr. Ludwig Lazarus Zamenhof as a bridge to break down language barriers between people. Esperanto was designed to function as an international auxiliary language, with the goal of fostering mutual understanding and promoting peace among people from different linguistic backgrounds.

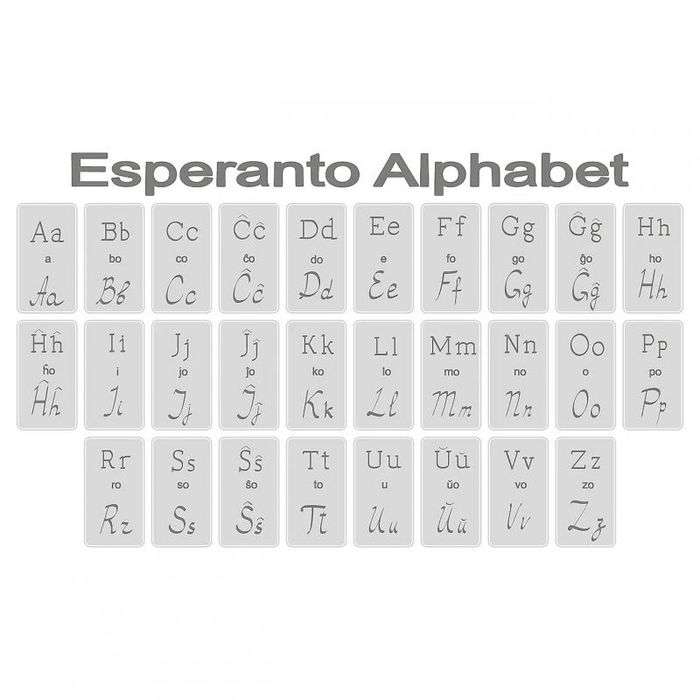

Esperanto's structure draws from a variety of languages. Its foundation is largely based on Latin, with influences from English, German, Russian, and the creator's native Polish. The language also follows 16 simple grammar rules, and thankfully, there are no exceptions to these rules. This means once you learn them, speaking becomes relatively straightforward, making Esperanto a language that is easy to learn and master for many.

7. Aymara: Andes, South America

The Aymara language is not inherently unusual, as it is spoken by over million people across the Andes mountains in South America, and it is an official language of Bolivia. However, there is something distinctly peculiar about it when you dive deeper. While most languages describe the future as something ahead of us, the Aymara language describes the future as something behind them. The basic word for ‘front’ or ‘eye/sight’ (nayra) also means ‘past,’ while the word for ‘back’ (qhia) refers to the ‘future.’

Aymara speakers even use gestures to express these concepts: they gesture behind them when talking about the future and in front of them when discussing the past. In Aymara culture, the future is something uncertain, unseen, and hidden, so it is metaphorically placed behind them. The past, on the other hand, is something already known and fixed, hence it is in front of them. This unique way of conceptualizing time is thought to be exclusive to the Aymara language, where what is known is in front, and what is unknown lies behind.

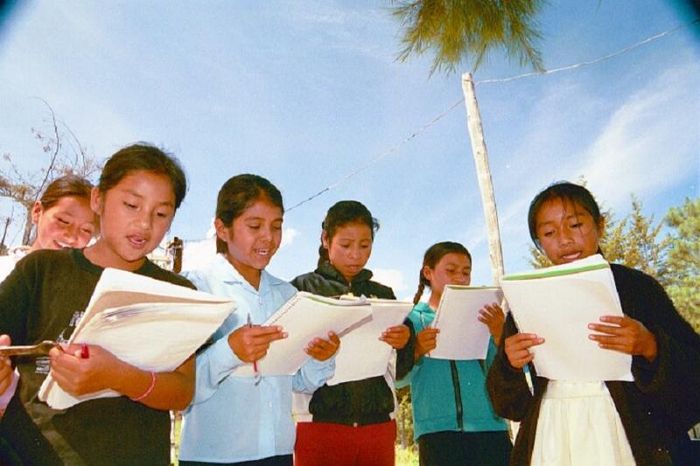

8. Mixtec: Oaxaca, Mexico

The Mixtec language, spoken by around 6,000 people in Oaxaca, Mexico, is often regarded as one of the most peculiar languages in the world, according to linguist Tyler Schnoebelen, trained at Stanford. But what exactly makes it so strange? Victor Mair summed it up succinctly in the University of Pennsylvania's Language Log: 'In this context, 'strange' refers to the presence of linguistic features that are markedly different from most other languages.'

Schnoebelen analyzed 2,676 languages worldwide using the World Language Structure Map, examining which languages shared 192 distinct linguistic traits and which did not. Based on this criterion, Mixtec stands out as an extraordinarily unique language. The most bizarre feature of Chalcatongo Mixtec is its complete lack of a clear method for forming yes-or-no questions.

In Mixtec, there is no distinct way to express whether something is a question or a statement. For example, the question “Is this strange?” and the statement “This is strange” are virtually indistinguishable. As Monica Ann Macauley points out in A Grammar of Chalcatzingo Mixtec, “There are no signs of an interrogative state (yes/no question) through a series of question markers, intonation, tone, or any other means.” According to Schnoebelen, Mixtec is the only language in the world with this feature.

9. Pirahã: Amazonas, Brazil

Spoken by the Pirahã people in Brazil, this regional language is notable for lacking terms for colors or numbers. While this might seem like a challenging concept for outsiders, the speakers of Pirahã communicate effectively without these features. Instead of specific colors like 'red' or 'purple,' they use terms like 'light' and 'dark' to describe shades. When discussing quantities, they use terms like 'many' or 'a few.'

Pirahã is also simpler than many other unusual languages. It has only about ten to twelve sounds. Additionally, communication often includes humming and whistling to make it even more straightforward. Rather than specific color terms, Everett claims they rely on equivalents like 'light' and 'dark.' For numbers, they keep it basic, using words like 'few' and 'many' (along with others like 'large,' 'group,' and 'small').

10. Tuyuca: Amazonas, Brazil

In 2009, The Economist referred to the Tuyuca language of eastern Amazon as 'the most difficult language in the world' for two main reasons. First, it's not widely spoken, with only about 1,000 speakers scattered across Colombia and Brazil. What makes it even more challenging to learn is that individual words are constructed to express ideas—meaning longer words convey what would typically require full sentences in most languages.

Tuyuca is classified as an agglutinative language, meaning it combines multiple morphemes, the smallest units of meaning, into a single word to perform the job of a full sentence. While agglutination doesn't inherently make a language difficult or unusual, Tuyuca introduces additional complexity. Its verbs require speakers to be aware of how they know something, and the language uses specific endings to indicate whether the speaker fully understands the topic being discussed.