1. Coral

Corals and Jellyfish belong to the Cnidarian family. Their bodies are asymmetrical, and both species use stinging cells to defend themselves. Although often mistaken for plants, corals are actually brainless animals. This sets them apart from plants: animals seek food, while plants produce it themselves. Corals, like animals, search for sustenance. They host a variety of tiny creatures, such as coral polyps that feed on oceanic plankton. These polyps catch plankton with their retractable tentacles and consume them.

A single "head" of coral is formed by thousands of genetically identical polyps, each only a few millimeters in diameter. Over many generations, these polyps create a skeletal structure that is characteristic of their species. Coral heads grow through asexual reproduction of the polyps, and they can also reproduce sexually by releasing gametes synchronously over one or more nights during a full moon.

Although corals use specialized cells called nematocysts in their tentacles to inject toxins and capture plankton, they mainly rely on symbiotic relationships with single-celled algae known as zooxanthellae for nutrition. This is why most corals depend on sunlight and thrive in shallow, clear waters, typically no deeper than 60 meters (200 feet). Corals significantly contribute to the physical structure of tropical and subtropical coral reefs, like the Great Barrier Reef off Queensland, Australia.

Some coral species do not need algae and can survive in deeper waters. For example, species in the Lophelia genus can live at depths of up to 3,000 meters in the Atlantic Ocean. Another example is the Darwin Mounds off the southwest coast of Cape Wrath, Scotland. Corals can also be found off the coast of Washington State and the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, USA.

2. Starfish

Starfish are relatives of sea urchins, but they are not fish. In fact, they can't swim at all. Starfish spend their entire lives at the ocean floor. While they may occasionally float or wash up on shores, this is never by choice! At the tip of each arm, starfish have tiny eyes that can sense light and darkness. Their lack of a brain doesn't hinder them; they rely on basic sensory cells to detect threats and food. Starfish can have anywhere from five to forty spiny arms. If a predator bites off one or two arms, the starfish can regenerate them.

Starfish play a vital role in the ecosystem and biological science. For example, the Pisaster ochraceus species has become widely known as a keystone species. The Acanthaster planci, a notorious predator of corals, can be found throughout the Indo-Pacific region. Other species, such as those in the Asterinidae family, are often used in developmental biology research.

Most species of starfish have separate sexes. Their genders are not easily distinguishable externally, as their gonads are hidden, but it becomes clear when they release eggs. Some species are hermaphrodites, producing both eggs and sperm simultaneously, while in a few species, the same gonad, called the gonopore, produces both. Other starfish are sequential hermaphrodites, changing sex over time.

Some starfish species can regenerate lost arms and even grow back entire limbs in a specific time period. The lifespan of starfish varies greatly between species. Generally, larger species live longer. The average starfish lifespan is around 10 years, with the longest recorded lifespan being 34 years.

3. Clam

Clams are brainless mollusks with compressed bodies inside a hinged shell. Other members of this family include oysters, mussels, and scallops. Clams have the ability to open and close their shells. They function through their nervous system, and are widely found in the fishing world due to their abundance and ease of harvesting. Clams possess kidneys, a stomach, a mouth, a nervous system, and a beating heart.

Clams use unique methods to obtain and consume their food. First, they can move slightly using a “foot” that helps them position themselves in the water for better nourishment. Unlike oysters, they don’t attach to surfaces but rather find food-rich areas and burrow in to forage.

Clams feed by filtering water through two siphons: one for intake and one for expulsion. The food particles, trapped in a slimy mucus, are carried by ciliary action to their mouths for consumption. They primarily feed on plankton, algae, and organic matter.

Clams also have an alternative nutritional strategy. Some species establish a symbiotic relationship with algae, like Zooxanthellae. These algae live within the clam’s shell. The mollusk provides nitrogen for the algae’s growth, while the algae supply various nutrients to the clam in return.

4. Giant Clam

Giant Clams, also known as Tridacna, are brainless mollusks with the largest pair of shells. These giants are among the most endangered species of clams. Native to the shallow coral reefs of the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, they can weigh over 200 kg (440 lbs), reach up to 120 cm (47 inches) across, and live for over 100 years in the wild. They are also found off the coast of the Philippines, where they are called Taklobo, and in the South China Sea on the coral reefs of Sabah (East Malaysia).

Giant Clams rely on Zooxanthellae algae for a massive portion of their nutrition. These single-celled algae absorb sunlight and convert it into energy, which is then transferred to the clam. This symbiotic relationship allows the clams to grow to their enormous size, even in nutrient-poor waters. The clams also support the algae by recycling nutrients, ensuring this bond remains vital and inseparable.

The primary threat to the survival of the Giant Clam is human activity. American and Italian scientists have conducted studies showing that the meat of the clam is rich in amino acids that stimulate human sexual desire, as well as high levels of zinc (which promotes testosterone production). This has led to overfishing for culinary dishes in China, Japan (for Himejako), France, and several Southeast Asian and Pacific countries. In the black market, their shells are sold as decorative pieces and souvenirs.

From 1985 to 1992, the Australian government initiated several breeding and conservation projects for Giant Clams at the Micronesian Cultivation Center in the Republic of Palau (Pacific), managed by James Cook University. The program aimed to preserve the rare genetic pool of the largest species in the clam family. In this controlled environment, clams were provided with ideal conditions for rapid reproduction, and once mature, they were released into natural coral reefs.

5. Portuguese Man-of-War

Do you think those transparent, balloon-like "sails" are jellyfish? Think again! Despite their resemblance to jellyfish, even scientists agree: these are actually siphonophores, not true jellyfish.

Siphonophores are brainless creatures with a form that mimics the shape of a sail, drifting aimlessly across the vast ocean surface. You are most likely to encounter them between September and December. Found in tropical and subtropical seas, their sail-like structure can rise as much as 15 cm above the water’s surface. Beneath the sail, thousands of long tentacles and polyps can stretch up to 50 meters in length.

Siphonophores have a clearly defined digestive cavity and utilize extracellular digestion, breaking down food into smaller pieces inside their gut before proceeding with intracellular digestion. Their gut, or digestive sac, has only a single opening (serving as both mouth and anus). When consuming large prey, they must fully digest one meal before expelling any indigestible parts before they can feed again. Consequently, they cannot store food for long and rely on rapid intracellular digestion to process the food they ingest quickly.

The body of a siphonophore is cylindrical, with a base to anchor itself to a surface and a mouth opening surrounded by eight long, retractable tentacles that are much longer than the body. These tentacles serve multiple functions: capturing prey, movement, and sensation. The body is radially symmetrical, elongated, and slender.

The tentacles of siphonophores are covered in stinging cells, used for both defense and capturing food. When hungry, they extend their tentacles into the surrounding water. Upon making contact with prey (such as a water flea), the stinging cells in the tentacles fire, paralyzing the prey. The tentacles then reel in the prey, bringing it to the mouth for digestion via intracellular processes.

6. Sponge

Sponge, or Poriferans, are fascinating creatures lacking a nervous system, digestive system, and circulatory system. Instead, they rely on the continuous flow of water through their bodies to obtain food, oxygen, and remove waste. An interesting fact about sponges is that they can ‘sneeze’ underwater. When a foreign object enters their system, they take in extra water and expel it to flush out the intruder, similar to how humans sneeze. Despite lacking a brain, sponges can still sense their environment in a unique way.

Although we often associate terms like “omnivores” and “carnivores” with most animals, these don’t apply to sponges. They have specialized feeding structures that allow them to filter food as water flows passively through their bodies, trapping whatever food particles come by. Since most of the food they capture is made up of bacteria and plankton, these microscopic creatures are their primary diet. These filter feeders thrive on extremely small organisms and particles, a niche that is quite specific to them.

In their natural habitats, sponges filter water and feed on microscopic organisms. While many people are familiar with plankton, sponges also consume viruses and bacteria suspended in the water. In fact, many animals rely on consuming tiny life forms in the ocean due to their abundance. If you were to weigh all the microscopic life in the ocean, it would account for 90% of the total biomass.

In addition to plankton, sponges feed on bacteria, viruses, archaea, protozoa, and fungi. Although most of these single-celled organisms are invisible to the naked eye, sponges digest them as they pass through. It may seem like not much is going on, but just one teaspoon of seawater could contain up to 100 million viruses.

7. Oyster

Oysters are brainless creatures that belong to the same family as clams. Known for the precious pearls found inside their shells, it’s a rare treasure hunt—your chances of finding a perfect pearl are about one in a million. Oysters are filter feeders, sifting the water to remove organic matter such as plankton for nourishment. They can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day, providing them with enough food to survive for extended periods.

As bivalve mollusks, oysters are part of the same family as clams, scallops, and mussels. They thrive along coastlines, rocky shores, and river mouths, often attaching themselves to stable surfaces like rocks or reefs. Oysters are also classified as marine shellfish, and their meat is considered a delicacy—sweet, rich in nutrients, and packed with protein, carbohydrates, fats, zinc, magnesium, and calcium. Oysters play a crucial role in the ecosystem by filtering impurities from the water and serving as a vital food source for coastal communities. Approximately 75% of the world’s wild oysters are found in five locations across North America.

Compared to smaller clams and scallops, oysters are relatively large, with their shells often much larger than their bodies. In fact, a notable example of an oyster was found at Plymouth Harbour, England, measuring 18 cm across and weighing almost 1.4 kg. According to Douglas Herdson, a female oyster of similar size can produce over three million eggs.

Some oyster species, such as Ostrea lurida and Ostrea edulis, are hermaphrodites, meaning their reproductive organs contain both eggs and sperm. For species like the Crassostrea rivularis (river oyster), the male-to-female ratio varies throughout the year. From July to November, males comprise 21-61% of the population, while females make up 40-68%. The highest reproductive activity occurs during this period. From November to April, the ratio shifts to 38-90% males and 0-16% females. Oysters typically spawn between April and October and can live up to 30 years.

8. Sea Lily

Sea lilies, also known as sea lilies, belong to the class Crinoidea within the animal kingdom. These fascinating marine creatures remain stationary on the ocean floor throughout their lives. Interestingly, research suggests that when they can no longer find food, sea lilies have the ability to drift to new locations. If necessary, they can move at speeds of up to 140 miles per hour.

Related to starfish, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers, sea lilies have a small mouth located at the center of their bodies, feeding primarily on organic material that sinks to the ocean floor. Like several other species on this list, sea lilies instinctively contribute to ocean health by filtering and cleaning the water. Typically, they can grow up to 30 inches long, though fossil records indicate that they once reached lengths of 80 feet.

One of the defining features of sea lilies is their mouth, surrounded by arms. They have a U-shaped digestive system, with their anus located near the mouth—this arrangement is unusual among other echinoderms. While most sea lilies have five symmetrical arms, many species possess more than five. Sea lilies also have a stalk-like structure used to anchor themselves to the seabed, though some free-swim as adults after initially attaching during their juvenile stages. Approximately 600 species of sea lilies still exist today, but their numbers were once much greater. Some limestone layers dating back to the late Paleozoic era are almost entirely composed of sea lily fragments.

Sea lilies consist of three main parts: the body, the flower cup, and the arms. The body is composed of highly porous skeletal elements connected by connective tissue. The flower cup contains the sea lily’s digestive and reproductive organs, with the mouth located at the top and the anus surrounding it—a feature uncommon among other echinoderms. The arms are divided into five symmetrical sections, each equipped with smaller bones and covered with cilia that help move organic material from the arms to the mouth.

Most sea lilies are capable of swimming freely and lack a stalk, while species that live in deep waters retain long stalks up to 1 meter (3.3 feet) in length, though they are often much smaller. The stalk grows from behind the mouth and resembles the upper part of other echinoderms like starfish and sea urchins, which sets sea lilies apart from most other echinoderms. The base of the stalk contains a disc-shaped suction structure, often covered with spiny appendages.

9. Sea Anemone

Sea anemones are unique, brainless creatures with a plant-like appearance. Despite their plant-like form, they are highly active and seek out food by using their long tentacles to capture and consume prey. One of their most remarkable abilities is their capacity to change shape. This transformation occurs by retracting and twisting the muscles in their tentacles. It’s truly amazing to watch as they change forms and sway in the water, demonstrating how animals can use sensory responses to interact with their environment, even without a brain.

Sea anemones are predatory animals that belong to the order Actiniaria, within the phylum Cnidaria, class Anthozoa, and subclass Hexacorallia. Anthozoans are typically characterized by large polyps that allow them to digest larger prey, and they lack a medusa phase. As cnidarians, sea anemones are closely related to corals, jellyfish, and hydras.

Sea anemones have a fascinating anatomy. They possess a tubular body with a diameter ranging from 1-5 cm and a length of approximately 1.5-10 cm. Due to a “pneumatic” mechanism, they can adjust their size. Some species, like Urticina columbiana and Stichodactyla mertensii, can grow as large as 1 meter.

Their tentacles, which surround the mouth, are equipped with cnidocytes, specialized cells that contain barbed stingers. These cells serve a dual purpose: defense and offense. Cnidocytes contain nematocysts, venom-filled capsules that, upon contact, rupture and paralyze their prey or any threat.

Additionally, sea anemones have large stomachs that can accommodate sizable meals. They possess an incomplete digestive cavity, with a single opening used for both ingesting prey and expelling waste. Their mouths are flat and feature grooves at one or both ends, which house siphonoglyphs that assist in transporting food to the gastrovascular cavity for digestion.

10. Sea Squirt

Sea squirt (ascidian) larvae are born with a brain, but as they mature and attach themselves to a fixed surface, their brain gradually disappears. Sea squirts also have the remarkable ability to seal wounds by regenerating cells. Despite being animals, they have a plant-like appearance.

However, sea squirts are only truly charming in their early stages. As larvae, they resemble tadpoles, complete with eyes, a brain, and a tail. Once they reach adulthood, they attach to a stationary surface such as a rock, ship hull, or coral. After becoming anchored, they absorb their body parts, leaving only a nerve cord. Their tiny brain is “recycled” into a digestive structure, leading to the folk belief that sea squirts “eat their own brain.”

Sea squirt species are numerous and found throughout the world’s oceans. As adults, they are incredibly sedentary, moving only a few centimeters a day. Their eyes, mouth, and nose disappear, making them resemble plants. But wait—perhaps many humans, as they age, also become more sedentary, just like the sea squirt!

Still, sea squirts are highly evolved animals due to their vertebrate-like structure. Known scientifically as Ascidian or Tunicate, they are also called Sea squirts because of the water stream they expel when they contract. Sea squirts are hermaphroditic, possessing both eggs and sperm, but since their eggs and sperm mature at different times, they must mate with another sea squirt instead of self-fertilizing.

11. Sea Urchin

Sea urchins are spiny creatures with sharp, pointed heads, and anyone walking barefoot on the beach is likely to encounter them in the worst way possible. Fortunately, outside of South Florida, these creatures are not venomous. Sea urchins have many tube feet that help them control their movement by adjusting the pressure and water flow inside their bodies, enabling faster movement. Their mouth is located underneath their body, and they expel waste from the top. These creatures sit on rocks, scraping and feeding on algae, which helps keep the ocean clean in many ways.

Sea urchins, also known as uni or sea hedgehogs, are marine creatures found throughout the world, particularly in tropical climates. They are often referred to as the "ginseng of the sea" due to their numerous health benefits, and their price is affordable for most people in our country.

Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea and are a type of echinoderm that typically lives on the seafloor or clings to rocky coastal areas. Their bodies are round, resembling a ball, and are covered with numerous black spines, much like a hedgehog. As they mature, sea urchins grow to about the size of a medium orange, slightly smaller than a grapefruit.

The breeding season for sea urchins occurs from March to July, so if you're traveling to the coast during this time, you'll have the chance to taste special dishes like grilled sea urchin or other delicacies made from them. Popular locations for sea urchins include the beaches of Da Nang, Nha Trang, and Phu Quoc.

12. Sea Cucumber

Sea cucumbers are worm-like creatures that feed on plankton wherever they can find it. Although they are extremely dangerous, they do not intentionally pose a threat as they lack brains. They can release a toxic substance called holothurin, which can cause permanent blindness in humans. Sea cucumbers instinctively search for food using tube-like feet around their mouths. Their diet mainly consists of marine invertebrates, algae, and organic matter. Oddly enough, despite their lack of brain function, these marine animals reproduce both sexually and asexually.

Sea cucumbers, also known as sea worms, sea pigs, or sandfish, are part of the class Holothuroidea. They have long bodies and leathery skin with internal spicules under their surface. Found worldwide in oceans, their English name, "Sea cucumber," comes from their cucumber-like appearance. In French, they are called "Bêche-de-mer," which translates to "sea spade."

Sea cucumbers primarily feed on dead organic matter found on the ocean floor, acting as the ocean's cleanup crew. They forage for food by lying in the current, catching drifting organisms with their tentacles when they spread out. Large populations of them can be found near fish farms or other aquaculture sites.

Sea cucumbers reproduce by releasing both eggs and sperm into the water. Depending on the weather conditions, one individual can release thousands of gametes at a time.

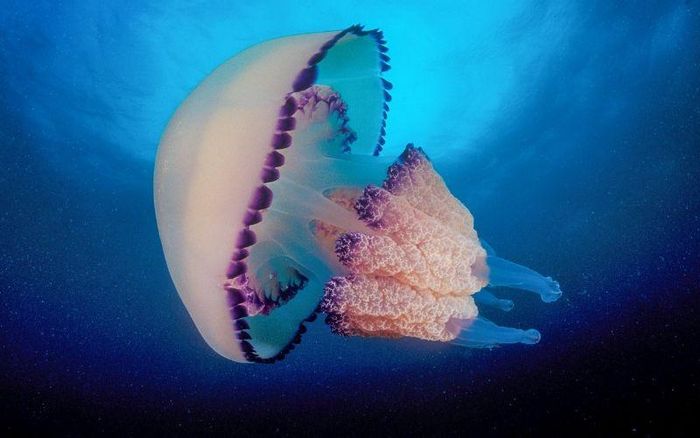

13. Jellyfish

Jellyfish drift with the ocean currents, but they also expel water to propel themselves forward. They operate through a network of sensory nerves. Their tentacles react to foreign objects with a sting, releasing a toxin that can incapacitate or kill an intruder.

Jellyfish lack a brain, heart, ears, head, legs, or bones. Their skin is so thin that they can absorb oxygen directly through it. Although they don't have a brain, they possess a simple nervous system with sensory organs that can detect light, vibrations, and chemicals in the water. These abilities, along with their sense of gravity, help jellyfish navigate and move effortlessly through the water.

Without a brain, jellyfish's movements are mainly passive, relying on the ocean currents to carry them. They don't actively hunt; instead, they wait for prey to encounter them. Their tentacles are covered with special cells called Cnidoblasts, which they use for both hunting and self-defense.

Essentially, jellyfish don't need a heart. The outer layer of a jellyfish, known as the Ectoderm, allows oxygen to diffuse into their bodies without the need for a circulatory system to pump blood. Furthermore, their digestive system is rudimentary, meaning neither respiration nor nutrient absorption requires complex organs like a heart.

Jellyfish also have a short tube-like structure suspended in the center of their bell-shaped bodies. This tube serves both as a mouth and a digestive organ. In some species, the tube is surrounded by a ribbon-like appendage that spirals through the water, often referred to as a mouth weapon or oral arms.