1. Diet

Although lacking real teeth, blue whales are classified as carnivores. Their diet mainly consists of small invertebrates, crustaceans, and occasionally small fish. Blue whales feed by swimming towards schools of prey, and their throat can expand due to folds in their neck, allowing them to gulp enormous amounts of water into a food pouch created in their lower jaw. Afterward, they expel the water while retaining thousands of tiny creatures caught by their baleen plates, which are then swallowed.

During the summer months in cold, food-rich waters, blue whales can consume up to 40 tons of prey daily. Despite their huge summer food intake, they hardly eat when migrating to warmer waters during the winter.

An adult blue whale can consume up to 40 million krill in a single day. They always feed in areas with the highest krill density, sometimes consuming up to 3,600 kilograms (7,900 lb) of krill in one day. The energy requirement for an adult blue whale is about 1.5 million kilocalories. Their feeding habits fluctuate seasonally, as they typically consume large amounts of krill in cold, nutrient-dense waters of the Southern Ocean before moving to warmer equatorial waters for breeding.

Blue whales usually dive up to 100 meters (330 feet) to forage during the day, while at night, they primarily hunt closer to the surface. They can continuously hunt for up to 10 minutes without resurfacing, with some documented dives lasting as long as 21 minutes. Blue whales often accidentally consume small fish, squid, and other tiny crustaceans as a result of their feeding technique.

2. Vocalizations

Blue whales are often called the wandering singers of the oceans. They produce ultra-low sounds at a frequency of 14 Hz, which is also the loudest sound in the world, louder than a jet engine at 200 decibels. In comparison, the human shout is about 70 decibels, and sounds above 120 decibels can be harmful to human ears.

The purpose of these vocalizations remains unclear. Some potential reasons proposed by Richardson et al. (1995) include:

- Maintaining distance between individuals

- Identifying species and individuals within species

- Communication (feeding, alerting, mating)

- Maintaining social organization (e.g., calls between males and females)

- Locating topographic features

- Marking the location of food sources

While the complex sounds of humpback whales (and some blue whales) are believed to be used primarily for sexual selection, simpler sounds from other whale species are used year-round. While toothed whales can use echolocation to detect the size and nature of objects, this ability has not been demonstrated in baleen whales. Moreover, unlike some fish like sharks, whales have poorly developed olfactory senses. Due to the limited visibility in water and the excellent transmission of sound underwater, the sounds heard by humans might also help in navigation. For example, the depth of water or the presence of large obstacles can be detected by the loud noises produced by baleen whales.

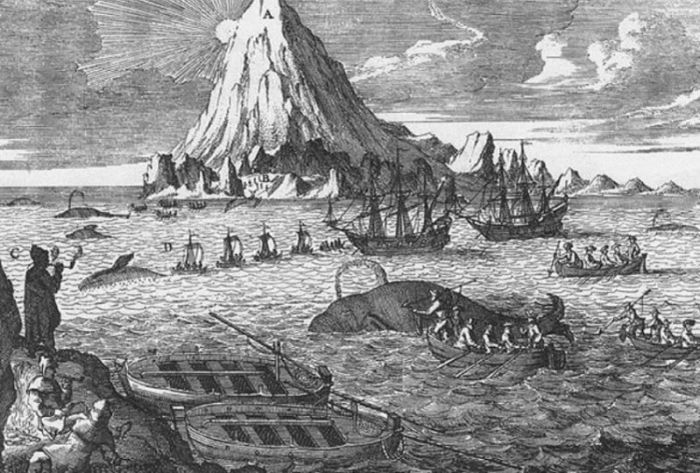

3. The Whaling Era

Blue whales are incredibly strong and swift, making them difficult to catch and kill. In the early days, whalers typically hunted sperm whales or Eubalaena species, seldom targeting the blue whale. However, in 1864, Norwegian whaler Svend Foyn made a breakthrough by attempting to hunt large whales using a steam-powered vessel and a specially designed harpoon gun. Though initially cumbersome and with low success rates, Foyn refined his technique, leading to the establishment of several whaling stations along Norway’s northern coast. These stations were eventually shut down due to local fishermen conflicts, with the last one closing in 1904.

Whaling spread quickly to Iceland (1883), the Faroe Islands (1894), Newfoundland (1898), and Spitsbergen (1903). In 1904-05, blue whales were first hunted at South Georgia, and by 1925, the introduction of slipways for easier whale recovery and the increased use of steam engines led to a dramatic decline in blue whale populations, as well as other baleen species, around Antarctica and nearby regions. In the 1930–31 whaling season alone, 29,400 blue whales were killed in Antarctica. By the end of World War II, blue whales seemed to be nearly extinct. In 1946, international whaling quotas were first introduced, but their impact was minimal, as rare species were still hunted alongside more abundant ones.

Arthur C. Clarke was one of the first intellectuals to advocate for the plight of the blue whale, calling attention to their destruction in his 1962 book, "Profiles of the Future," stating, "We do not know the true nature of the entity we are destroying," referring to the blue whale's large brain.

Traditional whale species in Asia were nearly wiped out by industrial whaling practices, particularly by Japan, affecting migratory populations traveling from northern Japan to the East China Sea. The last of these whales were captured between 1910 and 1939 in Amami Oshima. Intense whaling continued until 1965, with whaling stations located along the Hokkaido and Sanriku coasts.

Whaling was finally banned by the International Whaling Commission in 1966, and illegal whaling in the Soviet Union ended by the 1970s. By then, over 330,000 blue whales had been killed in the Antarctic, 33,000 in other parts of the Southern Hemisphere, 8,200 in the North Pacific, and 7,000 in the North Atlantic. The largest blue whale population in the Antarctic had been reduced to just 0.15% of its original size.

4. Current Blue Whale Conservation Efforts

Since the whaling ban was enacted, extensive research has been conducted to assess whether blue whale populations are increasing or stabilizing. In Antarctica, the most optimistic estimates suggest a growth rate of 7.3% per year since illegal whaling in the Soviet Union ceased. However, the total population remains under 1% of its pre-whaling numbers. In contrast, the California population has rebounded more swiftly, with a 2014 study indicating it has reached 97% of its original size.

In 2002, the global blue whale population was estimated to be between 5,000 and 12,000 individuals. However, data remains uncertain in many regions, and estimates are based on limited information.

Blue whales are listed as an endangered species in the IUCN Red List, and they have been under protection since the publication of the list. In the United States, the National Marine Fisheries Service has granted blue whales protection under the Endangered Species Act. The largest population, numbering around 2,800 individuals, is found in the Northeast Pacific, from Alaska to Costa Rica. During the summer, these whales can be observed off the coast of California. Occasionally, some members of this population also migrate to the northwest Pacific, between Kamchatka and northern Japan.

5. Other Threats Beyond Hunting

Due to their massive size, strength, and speed, blue whales have few natural predators. However, National Geographic once reported an incident where a blue whale was attacked by a pod of orcas off the Baja California Peninsula. Although the orcas were unable to kill the blue whale, it sustained severe injuries and died shortly afterward. Nearly a quarter of the blue whales in the Baja region bear scars from orca attacks.

Blue whales are also at risk from ship collisions and becoming entangled in fishing nets. The increasing use of sonar technology in maritime operations has interfered with their vocalizations, making communication difficult. Blue whales stop producing their signature D calls when a mid-frequency sonar wave is emitted, even though this frequency (1–8 kHz) lies outside their vocal range (25–100 Hz). The release of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are highly toxic to wildlife, poses another threat to blue whale recovery.

There are concerns that if glaciers and permafrost melt too rapidly due to global warming, the resulting influx of freshwater could disrupt the thermohaline circulation. This system, which regulates the movement of warm and cold ocean currents, is vital to the blue whale's migration patterns. Blue whales feed in cold, nutrient-rich waters at higher latitudes during the summer and migrate to warmer waters at lower latitudes to give birth during the winter. Disruption of these ocean currents could pose significant challenges for blue whale populations.

Rising sea temperatures also impact the blue whale's food sources. As temperatures increase and salinity decreases, the distribution of krill—the blue whale's primary food—could be significantly altered, leading to a decline in their availability.

6. The Blue Whale's Tongue Weighs More Than an Elephant

The blue whale is the largest animal ever to have lived on Earth, and it is also the heaviest. Its mouth is large enough to swallow an entire football team, and its heart is roughly the size of a small car. Generally, blue whales in the North Atlantic and Pacific are smaller than those found in waters near Antarctica.

The average weight for a 27-meter blue whale is around 150-170 tons, while a 30-meter whale, according to the National Marine Mammal Laboratory, can weigh as much as 180 tons. The largest blue whale identified by scientists weighed 177 tons and was a female.

With such a massive body, it’s no surprise that the blue whale’s body parts are equally enormous. For example, its tongue alone weighs an estimated 3 tons. In comparison, the average weight of an elephant is around 2.7 tons, which means the blue whale's tongue is heavier than an entire elephant.

Even in comparison to extinct creatures like dinosaurs, the blue whale still outshines them in size. One of the largest dinosaurs from the Mesozoic Era, Argentinosaurus, weighed about 90 tons, similar to the average weight of a blue whale. On the other hand, the famously long-necked dinosaur Amphicoelias fragillimus, which reached lengths of 58 meters and weighed an estimated 122.4 tons, still fell short of the blue whale’s weight.

7. A Baby Blue Whale Can Drink Between 380 to 570 Liters of Milk Daily

A baby blue whale can consume between 380 and 570 liters of milk each day. But how does a whale nurse without lips or cheeks to hold the milk? Blue whales evolved from land-dwelling mammals, possibly originating from a common ancestor with hoofed animals like pigs and hippos. They likely adapted to marine life around 50 million years ago.

A fully-grown blue whale can weigh more than 400 tons and live an average of 30 to 40 years, though some can reach up to 80 to 90 years. Not only are blue whales the largest mammals, but they are also the largest animals ever known. Males typically grow to 25 meters in length, while females can reach 26.2 meters. The longest blue whale ever discovered, in the South Atlantic in 1909, measured 38 meters.

Scientists believe blue whales start mating when they are between 5 and 15 years old. After successful mating, females are pregnant for 10 to 12 months. Their mating and birthing season typically takes place during the winter months. Unlike other whale species, blue whales are mostly solitary, but by late July and early August, they begin to pair up. Males will follow the females during this time.

A baby blue whale is born weighing approximately 2.5 tons and measuring 7 meters long. It can drink between 380 and 570 liters of milk daily, consuming 4,370 calories per kilogram, causing its weight to increase rapidly by about 90 kilograms every 24 hours. Blue whale calves are weaned at around 6 months of age. While nursing, the calf's tongue curls into a straw-like shape to draw in the milk. Whale anatomist Joy Reidenberg explains that this adaptation is vital, especially since they live in water and lack lips or cheeks to hold the liquid. The milk is thick, resembling toothpaste, and contains 50% fat.

8. The Heart of a Blue Whale Is About the Size of a Car

The heart of a blue whale has long been said to be about the size of a car. The aorta, according to some experts, is even large enough for a human to swim through.

For the first time, scientists have had the opportunity to study this giant organ, revealing new details about the massive creature that possesses it. Blue whales are currently the largest animals on Earth, with a body length that can reach up to 30.5 meters. Due to their rarity, scientists previously had no chance to study their heart structure in detail.

However, researchers had the chance to observe the heart closely after the carcass of a 23.3-meter-long blue whale washed ashore on Newfoundland's coast in May of the previous year. According to the BBC, the Royal Ontario Museum was tasked with performing an autopsy on the whale's body. The research team speculates that the unfortunate whale may have been struck by unusually thick ice floes or drowned after becoming trapped beneath the ice, unable to surface for air.

Weighing nearly 180 kg, the heart of the blue whale is about the same weight as a large truck tire and requires the strength of 3-4 people to lift. From the top of the aorta to the lowest chamber of the heart measures about 1.5 meters.

9. A Blue Whale's Carcass Can Explode When Washed Ashore

Blue whales, the largest animals on Earth, weighing up to hundreds of tons, cause significant problems when they wash ashore. Their massive size results in serious environmental issues during decomposition, including overwhelming odors. But that's not all – these massive carcasses can actually explode.

When an organism dies, bacteria and maggots begin the decomposition process rapidly. The internal organs break down first, producing gases such as methane and nitrogen compounds, causing the body to swell. In humans, the gas escapes through the decaying skin, but whale carcasses are different. Their thick, highly elastic skin can withstand immense pressure and decomposes very slowly, allowing gas to accumulate in dangerous amounts.

Imagine a whale weighing 170 tons. A creature of such size decomposing into gas is a ticking time bomb. Usually, this “bomb” only detonates when humans intervene. Curious onlookers often climb onto the whale to take pictures or cut off pieces of skin, meat, or teeth as souvenirs, unaware that even a small incision can cause the body to explode like a balloon. While the explosion is unlikely to be fatal, it can cause severe injuries. Moreover, being hit by the disgusting internal organs would be a disaster in itself.

The decomposition of a whale carcass can take up to 30 years, so leaving a bloated body near residential areas is not an option. In many places, the carcass is buried as soon as it is found. If the whale is too large, it is cut into smaller pieces. In extreme cases, when the body is too decomposed to bury or cut, explosives are used to dispose of the whale.

10. Blue Whales Can Spin 360 Degrees to Hunt Prey

Scientists recently discovered that blue whales perform underwater flips to attack prey from below. They recorded the impressive agility of these gigantic creatures and observed that they can rotate 360 degrees to reposition for a surprise strike.

The findings were published in the Royal Society Biology Letters by Dr. Jeremy Goldbogen and his team from the Cascadia Research Collective, based in Washington, USA.

Despite being the largest animals ever to exist, blue whales demonstrate remarkable skills in performing complex maneuvers while hunting plankton. To study how these massive creatures hunt, Dr. Goldbogen and his team attached activity trackers to a group of blue whales off the coast of Southern California.

The results showed that the whales executed impressive spinning maneuvers beneath the waves, diving into plankton clouds. As the whale submerged into the plankton-laden water, it continued spinning in the same direction, completing a full 360-degree rotation, before returning to balance and preparing for the next strike.

The researchers were able to capture video footage of these astonishing flips by using cameras attached to other whales to monitor this natural behavior. Previously, similar behavior was observed in other whale species, such as gray whales, but these animals rarely spin more than 150 degrees while hunting for plankton.

In smaller whale species, the ability to spin and change direction is believed to be due to their long fins and tails. However, for blue whales, scientists observed that these massive mammals are rewarded with a large meal for their acrobatic efforts.

11. How Do Blue Whales Spray Water?

The height, shape, and size of the water spouts produced by different whale species vary significantly. Blue whale spouts can reach up to 9-12 meters high. But how do they manage this? An explorer recently used a drone to capture stunning footage of a humpback whale off the coast of Newport, California. Normally, we only see the white jets of water emerging from a whale’s blowhole. However, from the drone’s perspective, the water jet catches a beam of sunlight, briefly creating a spectacular rainbow.

Although whales live in the ocean, they breathe through their lungs. This means these massive animals must surface periodically to inhale air. A whale’s blowhole is quite different from that of other mammals—it's a narrow tube leading to the lungs, and the nasal cavities are minimized. The blowhole opens on top of the whale's head, between its eyes. In some species, two blowholes merge into one. A blue whale’s lungs are enormous, weighing around 1,500 kg and capable of holding up to 15,000 liters of air. This large lung capacity helps the whale stay underwater for extended periods without needing to surface frequently. However, they cannot stay submerged for long—after about 10 to 15 minutes, the whale must surface to replenish its air supply.

To create such impressive spouts, whales must first exhale a large volume of air. Because the pressure in their lungs is high, the air is released with a loud sound, sometimes resembling the noise of a train’s whistle. The forceful air blast pushes seawater into the sky, creating a powerful jet. In colder waters, the air released from the whale’s lungs, which is warmer and more humid, encounters the colder outside air and condenses into tiny water droplets, further contributing to the water column produced.

12. Descriptive Information

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), also known as the 'whale of the deep,' is a member of the Mysticeti suborder (baleen whales). Measuring 25 to 27 meters (82 to 89 feet) in length and weighing between 160 to 180 tons (up to 200 short tons), it holds the record as the largest and heaviest animal ever to have lived.

With its long, streamlined body, the blue whale is often a blue-gray color on its back and lighter on its underside. There are at least three subspecies: B. m. musculus, found in the North Atlantic and North Pacific; B. m. intermedia, inhabiting the Southern Ocean; and B. m. Brevicauda (the pygmy blue whale), which resides in the Indian and southern Pacific Oceans. Like other whale species, their diet primarily consists of plankton and small crustaceans.

Before the 20th century, blue whales were plentiful across most of the world's oceans. However, over the past century, their numbers were drastically reduced due to whaling, bringing them to the brink of extinction. International protection laws enacted in 1966 helped to safeguard the species. A 2002 report estimated that between 5,000 and 12,000 blue whales still exist globally, including at least five distinct populations. Prior to intense hunting, the largest population in the Southern Ocean was around 239,000 individuals (ranging from 202,000 to 311,000). Smaller populations of around 2,000 individuals are found in the Northeast Pacific and Antarctic regions, with additional populations in the North Atlantic and at least two in the Southern Hemisphere. By 2014, the population of blue whales off the coast of California had nearly rebounded to pre-whaling numbers.

13. Classification

The blue whale belongs to the Balaenopteridae family, which includes species like the humpback whale, fin whale, Bryde's whale, sei whale, and minke whale. It is believed that the Balaenopteridae family diverged from other Mysticeti families around the middle of the Oligocene period (28 million years ago).

Blue whales are commonly classified as one of the eight species within the Balaenoptera genus. However, one researcher suggested placing them in a separate, monotypic genus, Sibbaldus, though this proposal has not been widely accepted. DNA analysis has revealed that the blue whale is more closely related to the sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) and Bryde's whale (Balaenoptera brydei) than to other Balaenoptera species. It is also more genetically similar to the humpback whale (Megaptera) and gray whale (Eschrichtius) than to the minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata and Balaenoptera bonaerensis).

There are documented cases of at least 11 natural hybrids between blue whales and fin whales. Arnason and Gullberg described the genetic difference between blue whales and fin whales as being similar to the distance between humans and gorillas. Researchers in Fiji believe they have captured an image of a hybrid between a humpback whale and a blue whale.

The first recorded description of the blue whale appeared in Robert Sibbald's *Phalainologia Nova* (1694). In September of 1692, Sibbald discovered a stranded whale in the Firth of Forth—a male measuring 24 meters (78 feet) long.

Authors have classified the species into three subspecies: B. m. musculus, found in the North Atlantic and North Pacific; B. m. intermedia, found in the Southern Ocean; and B. m. brevicauda, the pygmy blue whale, found in the Indian Ocean and Southern Pacific. There is also a controversial subspecies, B. m. indica, found in the Indian Ocean. Although B. m. indica was described earlier, it may be synonymous with B. m. brevicauda.

14. Size

The blue whale is the largest known animal to have ever existed on Earth. To put its size in perspective, the Argentinosaurus, one of the largest dinosaurs from the Mesozoic era, weighed only 90 tons, about the same as an average blue whale. The blue whale has a massive, sleek body that helps it glide effortlessly through the water. Its smooth blue-gray skin is complemented by a lighter belly and a series of expandable pleats on its throat, which stretch four times their size when the whale feeds.

The blue whale's tail is straight and split into two large flukes that push its immense body through the water with ease. As part of the toothless whale family, it doesn't have teeth but has approximately 395 baleen plates in its upper jaw, which it uses to filter food from the water. Like its relatives, the blue whale has two blowholes on top of its head to expel air and seawater when it surfaces to breathe.

During the first seven months after birth, a blue whale calf consumes around 400 liters (110 US gallons) of milk daily, causing it to gain approximately 90 kilograms (200 pounds) every 24 hours. At birth, the calf already weighs about 2,700 kilograms (6,000 pounds), equivalent to the weight of a full-grown hippopotamus. Despite its enormous size, the blue whale's brain is relatively small, weighing just 6.92 kilograms (15.26 pounds), or about 0.007% of its body weight. The blue whale also holds the record for the largest penis of any living creature, with an average length ranging from 2.4 meters (8 feet) to 3.0 meters (10 feet).