The debate over the color of the white-green - yellow-black dress that once went viral on the Internet raised new questions about the relationship between perception and consciousness.

Back in 2015, before Trump, before the Bitcoin boom or the QAnon conspiracy and Covid-19 wave, the disagreement over the color of a dress seemed to have 'broken the internet.' The famous Washington Post even called it a 'planet-splitting TV show.'

The dress became a meme, originating from a widely circulated photo that appeared across various media and social platforms for several months. For some, when they looked at the photo, they saw a black and green dress. For others, the dress was white and gold.

The legendary controversy about the dress.

Whatever people saw when they looked at it, they couldn't see it differently. If the photo didn't attract so much attention, perhaps you never knew that some people perceived it in a completely different way. But because social media is social media, having millions of people see a dress differently from how you see it created an incredibly strong reaction. With confidence in their eyes, you would consider those who saw the dress with different colors clearly as a mistake, even possibly a madness. But simultaneously, as the story of the dress began to spread on the internet, a tangible sense of fear about the nature of what is and isn't real also spread quickly, much like the photo itself.

The hashtag #TheDress appeared at a rate of 11,000 tweets per minute at its peak, and articles analyzing this photo even garnered millions of views within the first few days.

But for some scientists, especially in the field of neuroscience, the dress is an introduction to something this industry has understood for a long time: Reality itself is an experience, not a perfect 1-1 representation of the world around us.

The world, as you experience it, is a simulation running inside your skull, a dream while you're awake. Each of us lives in a perpetual virtual landscape of imagination and self-created illusions - a perception constantly updated as we bring in new experiences through our senses and think new thoughts about what we've perceived.

Before the existence of the dress, a well-understood issue in neuroscience was that all reality is virtual. Thus, largely consensual realities are the result of geographical factors. That is, individuals growing up in similar environments tend to have similar brains and therefore similar virtual realities. If they have something non-consensual, it's usually an idea, not a raw truth in their perception.

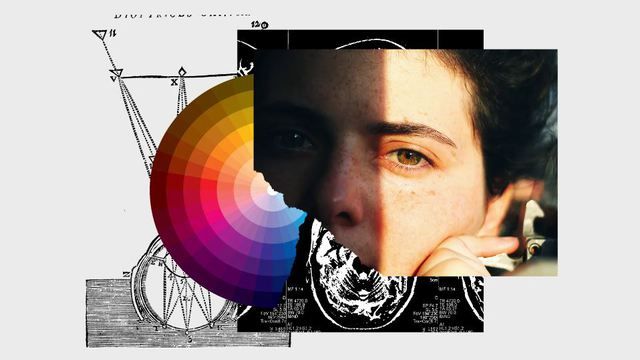

What color you see the dress is determined by your brain.

Pascal Wallisch, a neuroscientist researching consciousness and perception at New York University. When Pascal first saw the dress photo, it seemed to him clearly white and gold. But when he showed it to his wife, she saw something strange. She said it was clearly black and blue.

“That entire night, I stayed awake, pondering what could explain this,” he shared.

Thanks to years of studying light receptors in the retina and the nerve cells they connect with, Pascal thought he had understood about thirty steps in the image processing chain, but “all of that expanded in February 2015 when the dress appeared on social media'. This scientist felt like a biologist reading information that doctors had just discovered a new organ in the body.

The visible light spectrum - the basic colors we call red, green, and blue - are specific wavelengths of electromagnetic energy, Pascal explained. These energy wavelengths come from various sources, like the sun, lights, candles, etc. For example, when that light hits a lemon, the lemon absorbs some of those wavelengths, and the rest bounce off. Whatever remains goes through a hole in our heads called the pupil and hits the retina at the back of our eyes, where it all turns into the electrical stream of nerve cells that the brain then uses to create the subjective experience of seeing color. Because most natural light is a combination of red, green, and blue, a lemon will absorb the blue wavelengths, leaving the red and green colors to shine onto our retina, which the brain then combines into the subjective experience of seeing a yellow lemon. Color, in reality, only exists in the mind. In consciousness, yellow is part of imagination. The reason we tend to agree that lemons are yellow is that all our brains create similar imaginary images when light shines on a lemon and then bounces into our heads.

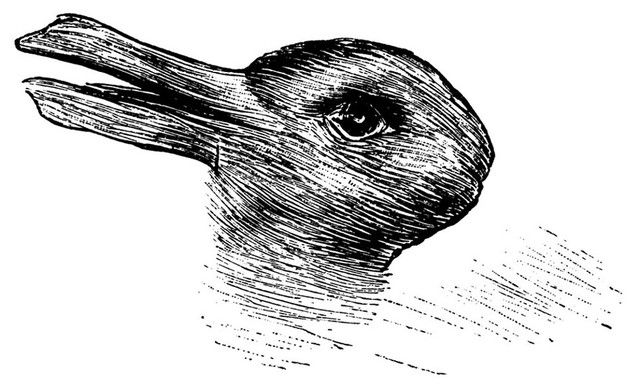

If we don't agree on what we see, it's often because the image is unclear in some way, and one person's brain is interpreting the image differently from another. Pascal says that in neuroscience, typical examples of this distinction are stable visual illusions, because each brain will solve in one way of interpretation at a time, and stable (having 2 stable states) because every brain processes in two similar ways. You may have seen a few examples of this, like an image of an animal sometimes looking like a duck and sometimes like a rabbit. Or the Rubin vase, sometimes looking like a vase and sometimes looking like two people facing each other.

Like all two-dimensional images, whether it's paint splatters or pixels on a screen, if the lines and shapes seem similar enough to things we've seen in the past, we will differentiate them into the Mona Lisa, a sailboat, or in the case of an unstable visual image, a duck or a rabbit. But the dress is something newer, a parallel adjacent visual illusion. It can be differentiated because each brain solves and gives an explanation at one time but alternates because each brain only decides in one of the two feasible interpretations. That's what makes the dress perplexing to Pascal.

Similar light goes into everyone's eyes, and all those brains are interpreting the lines and shapes like a dress, but somehow, all those brains don't turn that dress into the same color. Something is happening between perception and consciousness, and he wants to know what it is. So, this scientist sought funding and shifted the focus of his lab at New York University to unravel the mystery of the dress while this image was still circulating.

Pascal's intuition suggests that different people saw different dresses because when unsure of what we see, in the intermediate territory between unfamiliar and vague, we distinguish everything using anchor values. These are pattern recognition layers created by neural pathways, burned from within by experiences with the rules in the external world. The term originates from statistics and means any assumption the brain brings from the outside world will appear based on how it appeared in the past. But the brain goes even further. In situations Pascal and his colleague Michael Karlovich call 'considerable uncertainty,' the brain will use its experience to create illusions of what should be but isn't. In other words, in novel situations, the brain often sees what it expects.

Pascal says this has been clarified in the issue of color vision. We can recognize a green sweater even though our wardrobe is very dark, or a blue car under a night sky full of clouds, because the brain will make slight adjustments to the image to help us in situations where different light conditions alter the appearance of familiar objects. Each of us possesses an adjustment mechanism to recalibrate our visual system to “reduce brightness and achieve color constancy to maintain object recognition when brightness changes significantly.” It does so by altering what we experience to fit what we have experienced before. There's an excellent example of this in an optical illusion created by vision researcher Akiyoshi Kitaoka.

Optical illusion by Akiyoshi Kitaoka.

It looks like a red strawberry, but the image doesn't contain any red pixels. When you look at the picture, no red light enters your eyes. Instead, the brain assumes the image is overly lit by blue light. So, it automatically lowers the contrast a bit and adds some color where it thinks it's been erased, meaning the red color you experience when looking at those strawberries doesn't originate from the image. If you've grown up eating strawberries and throughout your life seen strawberries as red, when you see the familiar shape of a strawberry, your brain will assume they must be red. The red color you see in Kitaoka's illusion is created from within, an assumption made after a reality you don't know, or a lie your visual system tells you to provide you with what must be the truth.

Pascal believes the image of the dress is likely a rare, naturally occurring version of a similar phenomenon. The image was probably overexposed, making reality blurry, and everyone's brains differentiated it by “diminishing the light” they thought was present but we were unaware of.

The picture was clearly taken on a gloomy day. It was shot with an inexpensive phone. Part of the image is bright, and the rest is blurry. The light is unclear. Pascal explains that the color appearing in each brain is different depending on how each brain distinguishes light conditions. For some, it distinguishes the blur as black and blue; for others, it's white and gold. Like with strawberries, the human brain accomplishes this by telling lies, by creating a light condition that isn't there. According to Pascal, what makes this image distinct is different brains telling different lies, thus dividing humans into two factions with dissimilar subjective realities.

Following that hypothesis, Pascal believes he has an explanation for this. After two years of research with over 10,000 participants, Pascal identified a clear pattern among his subjects. The more time a person spends exposed to artificial light (mostly yellow) - especially someone working indoors or at night - the more likely they are to say the dress is black and blue. It's because they unconsciously perceive, at the level of visual processing, that it's artificially lit. Consequently, their brains eliminate the yellow, leaving darker shades, i.e., somewhat green. On the contrary, someone spending more time exposed to natural light - those working during the day, outdoors, or near windows - tends to eliminate the blue and sees it as white and gold. However, the haze is never confirmed.

Though people see colors subjectively, the image never seems blurry because conscious individuals only experience the output of the analysis process in their brains. And the output will differ depending on one's previous experiences with light. The result is their brains lied to them that the sensation is the truth.

Do you see a duck or a rabbit?

Pascal's lab coined a term for this: SURFPAD. When you combine Substantial Uncertainty with Ramified or Forked Priors, you get Disagreement.

In other words, when the truth is uncertain, our brains resolve that uncertainty we don't know by creating the most likely reality they can imagine based on our past experiences. Those with brains eliminating that uncertainty in similar ways will see agreements, like those seeing the dress as black and blue. Others with brains resolving that uncertainty differently will also see themselves aligned, as people who see the dress as white and gold. The essence of SURFPAD is both groups feel certain, and amid like-minded individuals, it seems those who disagree with them, regardless of their numbers, are confused. In each group, people then start seeking reasons why those in the other group can't see the truth, without going in a direction that likely they're not seeing the truth.

When faced with new ambiguous information, we inadvertently assess it based on what we've experienced in the past. But starting from the perceptual level, different life experiences can lead to very different differentiations, thus very different subjective realities. When that happens with substantial uncertainty, we can vehemently disagree about the nature of reality. But since no one on both sides is cognizant of the brain processes leading to that disagreement, it makes those perceiving everything differently, in a readily understandable way, wrong.

Check out Wired for reference