After over 20 months since the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the world has recorded over 219 million cases and over 4 million deaths. Humanity has endured numerous phases of the pandemic with variants becoming increasingly dangerous. However, the biggest unanswered question remains the origin of the virus, the answer to which holds the key to understanding all that has unfolded over the past nearly 2 years. So, why is this question so difficult to answer?

After over 20 months since the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the world has recorded over 219 million cases and over 4 million deaths. Humanity has endured numerous phases of the pandemic with variants becoming increasingly dangerous. However, the biggest unanswered question remains the origin of the virus, the answer to which holds the key to understanding all that has unfolded over the past nearly 2 years. So, why is this question so difficult to answer? Most experts didn't seem surprised by the seemingly empty-handed outcome of the 90-day investigation by the U.S. intelligence community into the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A brief summary released on August 27 revealed a noteworthy point that the virus 'was not developed as a biological weapon'.

Most experts didn't seem surprised by the seemingly empty-handed outcome of the 90-day investigation by the U.S. intelligence community into the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A brief summary released on August 27 revealed a noteworthy point that the virus 'was not developed as a biological weapon'.Why is tracing the origin so crucial?

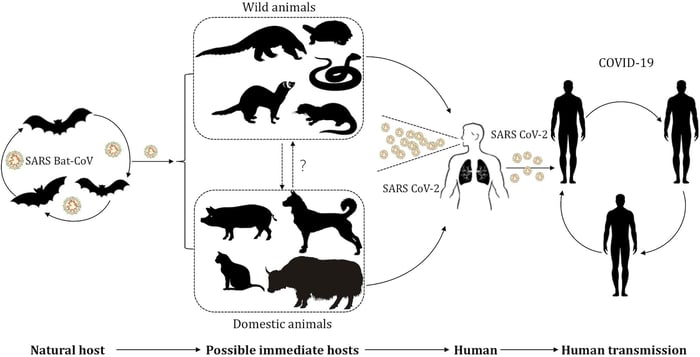

Understanding where, when, and how a pandemic starts is of utmost importance for healthcare officials. They are tirelessly working day and night to find ways to control the spread of the virus and prevent future outbreaks and mutations. For example, if the virus spreads from bats or other animals to humans, as the initial hypothesis suggested last year, preventive measures such as limiting contact between animals and humans will be emphasized. Additionally, monitoring animals and humans living nearby could provide crucial information to reduce the likelihood of virus spread in the future. This outcome could also lead to making larger-scale policy decisions to curb deforestation - the habitat of animals, and limit human settlements in hotspots of those species. Knowing the origin of the disease also leads to changes in human behavior, such as banning the consumption of wild animal meat or products, and cracking down on illegal wildlife trade.In the event that the virus leaked from a laboratory, scientists and policymakers would find safer ways to study this pathogen. This is why scientists have strongly supported the U.S. investigation into the origin of COVID-19. However, this question has persisted for too long, taking months, even years, but this mystery remains unanswered.

This outcome could also lead to making larger-scale policy decisions to curb deforestation - the habitat of animals, and limit human settlements in hotspots of those species. Knowing the origin of the disease also leads to changes in human behavior, such as banning the consumption of wild animal meat or products, and cracking down on illegal wildlife trade.In the event that the virus leaked from a laboratory, scientists and policymakers would find safer ways to study this pathogen. This is why scientists have strongly supported the U.S. investigation into the origin of COVID-19. However, this question has persisted for too long, taking months, even years, but this mystery remains unanswered. Earlier this year, a World Health Organization (WHO) investigative team visited the city of Wuhan, China to reassess the evidence provided by China regarding the origin of SARS-CoV-2. The WHO concluded that it is 'highly likely' the original virus spread from infected bats to humans through an intermediate animal. This mirrors the case of the SARS-CoV outbreak in 2002, the first pandemic of the 21st century. Then, the virus was believed to have spread from horseshoe bats living in a cave in China to civets sold in a wild animal market, and then to humans. Similarly, the MERS-CoV outbreak in 2021 was also suspected to have originated from bats transmitted to dromedary camels before infecting humans.WHO's report also suggests that the virus leaking from the Wuhan Institute of Virology is 'extremely unlikely'. Upon its release, this hypothesis sparked strong reactions from scientists and governments worldwide. The world believes it is too early to rule out the possibility of a lab leak. Meanwhile, other experts warn that political motives may have led to premature conclusions.

Earlier this year, a World Health Organization (WHO) investigative team visited the city of Wuhan, China to reassess the evidence provided by China regarding the origin of SARS-CoV-2. The WHO concluded that it is 'highly likely' the original virus spread from infected bats to humans through an intermediate animal. This mirrors the case of the SARS-CoV outbreak in 2002, the first pandemic of the 21st century. Then, the virus was believed to have spread from horseshoe bats living in a cave in China to civets sold in a wild animal market, and then to humans. Similarly, the MERS-CoV outbreak in 2021 was also suspected to have originated from bats transmitted to dromedary camels before infecting humans.WHO's report also suggests that the virus leaking from the Wuhan Institute of Virology is 'extremely unlikely'. Upon its release, this hypothesis sparked strong reactions from scientists and governments worldwide. The world believes it is too early to rule out the possibility of a lab leak. Meanwhile, other experts warn that political motives may have led to premature conclusions.How do experts search for viruses?

Tracing the origin of a virus requires field research, forensic science, and a bit of luck. Scientists may have to work hard for many years to find evidence pointing to the source, the root of the problem. For diseases originating from animals, that evidence often lies in genetic similarities between the virus sequences obtained from animals and the first cases. The match may not be 100% because viruses mutate or acquire new genes over time and when they jump to a host. But with enough time and luck, scientists have found nearly perfect results of around 99% for some types of viruses, such as those causing the two previous coronavirus outbreaks.

Tracing the origin of a virus requires field research, forensic science, and a bit of luck. Scientists may have to work hard for many years to find evidence pointing to the source, the root of the problem. For diseases originating from animals, that evidence often lies in genetic similarities between the virus sequences obtained from animals and the first cases. The match may not be 100% because viruses mutate or acquire new genes over time and when they jump to a host. But with enough time and luck, scientists have found nearly perfect results of around 99% for some types of viruses, such as those causing the two previous coronavirus outbreaks.What the world knows about the origin of COVID-19

The main difference between the SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 outbreaks is that scientists have been able to identify the intermediate animal hosts within a few months of the outbreaks for SARS and MERS, whereas for COVID-19, this remains unclear. Starting in December 2019, when the first COVID-19 cases were detected in Wuhan linked to the Huanan Seafood Market, Wuhan. The market sells a variety of wild animals including raccoon dogs, civets, rabbits, bats, mice, snakes, etc. The market was quickly shut down, and samples were taken from vendors and related individuals. According to statistics from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, over 900 samples were taken from the Huanan Seafood Market, including samples from surfaces of objects in the market, drainage systems, etc., resulting in the detection of 73 samples positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.The Chinese CDC also collected over 2,000 fecal and body fluid samples from live or frozen animals sold in the Huanan Seafood Market and other markets in Wuhan, but all tested samples were negative for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In some cases, antibodies against the virus were even detected. However, this sampling still misses many live animals and items commonly sold in the market when it was open.

Starting in December 2019, when the first COVID-19 cases were detected in Wuhan linked to the Huanan Seafood Market, Wuhan. The market sells a variety of wild animals including raccoon dogs, civets, rabbits, bats, mice, snakes, etc. The market was quickly shut down, and samples were taken from vendors and related individuals. According to statistics from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, over 900 samples were taken from the Huanan Seafood Market, including samples from surfaces of objects in the market, drainage systems, etc., resulting in the detection of 73 samples positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.The Chinese CDC also collected over 2,000 fecal and body fluid samples from live or frozen animals sold in the Huanan Seafood Market and other markets in Wuhan, but all tested samples were negative for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In some cases, antibodies against the virus were even detected. However, this sampling still misses many live animals and items commonly sold in the market when it was open.

To date, the closest relatives of the Corona virus, named RaTG13, were discovered in a species of horseshoe bat in a cave in Yunnan. In 2012, 6 miners fell ill, and 3 of them died from a respiratory illness. RaTG13 shares up to 96.2% genetic similarity with SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Another virus called RmYN02 found in the feces of Malayan horseshoe bats in Yunnan in 2019 also shows a 93.3% match.Moreover, scientists have identified viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 in 2 bat species outside China. Matches over 90% seem high, but genetically, it's not enough. According to Bart Haagmans, a virologist at Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands: 'The problem is bats are everywhere, they have many species with a diversity of viruses. So, it's very difficult to find the bats carrying the first outbreak virus.'

To date, the closest relatives of the Corona virus, named RaTG13, were discovered in a species of horseshoe bat in a cave in Yunnan. In 2012, 6 miners fell ill, and 3 of them died from a respiratory illness. RaTG13 shares up to 96.2% genetic similarity with SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Another virus called RmYN02 found in the feces of Malayan horseshoe bats in Yunnan in 2019 also shows a 93.3% match.Moreover, scientists have identified viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 in 2 bat species outside China. Matches over 90% seem high, but genetically, it's not enough. According to Bart Haagmans, a virologist at Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands: 'The problem is bats are everywhere, they have many species with a diversity of viruses. So, it's very difficult to find the bats carrying the first outbreak virus.'Why does suspicion of a lab leak still persist?

Many scientists believe SARS-CoV-2 has a natural origin, not a lab product. For instance, in a March 2020 Nature Medicine study, Kristian Andersen's team at California, virologists, highlighted genetic features characteristic of SARS-CoV-2 found in nature. However, despite much support for its natural origin, the lab leak hypothesis continues to attract attention from scientists, politicians, and the public. In fact, much of the skepticism stems from the disease's epicenter being close to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The center researches viruses in bats, a striking coincidence. Moreover, there are rumors that experts and staff at the Wuhan Institute of Virology were infected even before the first cases in Wuhan were reported.In a scientific report on May 14, some scientists argued that the possibility of a lab leak was not adequately considered in the WHO investigation. In a press briefing on March 30, Peter Ben Embarek, the leader of the WHO team investigating in China, stated: 'Because the lab leak hypothesis was not the main focus of the investigation, it did not receive as much attention and focus as other hypotheses.'

In fact, much of the skepticism stems from the disease's epicenter being close to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The center researches viruses in bats, a striking coincidence. Moreover, there are rumors that experts and staff at the Wuhan Institute of Virology were infected even before the first cases in Wuhan were reported.In a scientific report on May 14, some scientists argued that the possibility of a lab leak was not adequately considered in the WHO investigation. In a press briefing on March 30, Peter Ben Embarek, the leader of the WHO team investigating in China, stated: 'Because the lab leak hypothesis was not the main focus of the investigation, it did not receive as much attention and focus as other hypotheses.' In reality, laboratory virus leaks are not unprecedented. In Singapore, Taiwan, China, 4 researchers working in SARS virus labs inadvertently contracted the disease after the initial outbreak. In 2014, dozens of workers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta may have been exposed to anthrax bacteria due to safety protocol violations.Therefore, considering history, the lab leak hypothesis is not entirely implausible. 'The unfortunate thing is that information remains opaque, so things remain unclear. All information seems to be politicized, which is regrettable.'According to Natgeo

In reality, laboratory virus leaks are not unprecedented. In Singapore, Taiwan, China, 4 researchers working in SARS virus labs inadvertently contracted the disease after the initial outbreak. In 2014, dozens of workers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta may have been exposed to anthrax bacteria due to safety protocol violations.Therefore, considering history, the lab leak hypothesis is not entirely implausible. 'The unfortunate thing is that information remains opaque, so things remain unclear. All information seems to be politicized, which is regrettable.'According to Natgeo