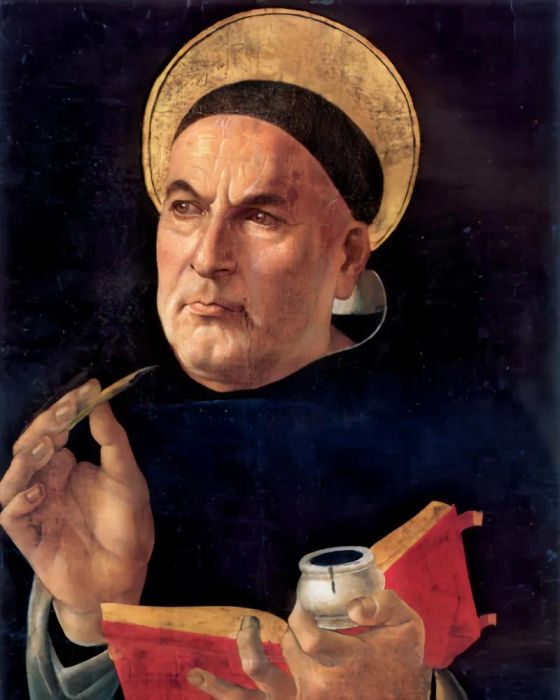

1. Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus was born on February 19, 1473. A Renaissance intellectual, he worked as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic priest. There is some uncertainty over whether Nicolaus officially became a priest, as evidence only shows he held minor clerical roles (like that of a chaplain). Nonetheless, his renown and the likelihood that he was ordained place him among the individuals on this list.

In the early 1500s, Nicolaus Copernicus was the first to propose that Earth was not the center of the universe, but rather that it and other celestial bodies revolved around the sun. While his model wasn't entirely accurate, it laid the groundwork for future scientists such as Galileo, who would expand and improve humanity's understanding of celestial motion. He sparked the Copernican Revolution, referring to the shift from the Ptolemaic view of the cosmos (with Earth at the center) towards the heliocentric model, placing the sun at the center of our solar system. This marked the beginning of the 16th-century Scientific Revolution.

After Nicolaus' father died while he was a child, his uncle became a father figure. His uncle hoped Nicolaus would become a priest in the Catholic Church. However, during his visits to various institutions, Nicolaus spent more time studying mathematics and astronomy. While studying at the University of Bologna, he lived and worked with astronomy professor Domenico Maria de Novara, who helped him observe the sky. Despite his uncle's influence, Nicolaus became a clergyman in Warmia, northern Poland, though he had not yet been ordained.

Nicolaus Copernicus passed away on May 24, 1543, from a stroke at the age of 70. In 2010, his remains were blessed by high-ranking Catholic clergy in Poland before being reburied. His grave is marked by a black granite stone, decorated with a model of the solar system, symbolizing his scientific contributions and his service as a priest of the Church.

2. Pope Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII was born on January 7, 1502. His birth name was Ugo Boncompagni. He led the Catholic Church and ruled the Papal territories from May 13, 1572, until his death in 1585. He is most renowned for implementing and lending his name to the Gregorian Calendar (the civil calendar), which became the standard calendar in Europe and much of the world, still in use today.

Pope Gregory XIII made significant contributions to the Catholic Church's life, including in the areas of Rome, education, the arts, and diplomacy. Before ascending to leadership, he had a distinguished career in law in Bologna, where he earned doctorates in both civil and canon law. He also taught law, including the theory and philosophy behind legal systems.

The intellectual influence of Pope Gregory XIII made him a trusted figure in legal and diplomatic circles, even before his election as pope in the 1572 conclave. Upon being elected, he took the name Gregory in honor of Pope Gregory I, who had lived in the 6th century.

His initiatives, including the restoration of vital infrastructure like gates, bridges, and fountains, were part of a broader vision to emphasize the importance of law in both Rome’s history and its culture. This was reflected in a statue of him in the Aula Consiliare of the Senatorial Palace. Along with his urban planning efforts, he also supported the use of artworks and architectural projects to turn Rome into not just the spiritual center of Catholicism, but also a beacon of Renaissance culture. In the Sala Regia of the Vatican, Pope Gregory XIII oversaw a series of frescoes depicting Christianity’s victory over its adversaries. He also authorized the entire map gallery in the Apostolic Palace to demonstrate the global spread of Christianity.

Additionally, the Gregorian Calendar reform marked a major shift in timekeeping. October 4, 1582, was directly followed by October 15, aligning the calendar with astronomical reality. This adjustment was gradually adopted by Protestant countries and has had a lasting impact on the world's timekeeping methods.

A notable monument to Pope Gregory XIII can be found at St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, completed in 1723 by Milanese sculptor Camillo Rusconi. It combines symbols of both religion and intellect, personified by two statues beside the pope. This monument honors a pontiff whose papacy is characterized by the interplay of faith, intellect, and reform, and is now considered foundational in European history.

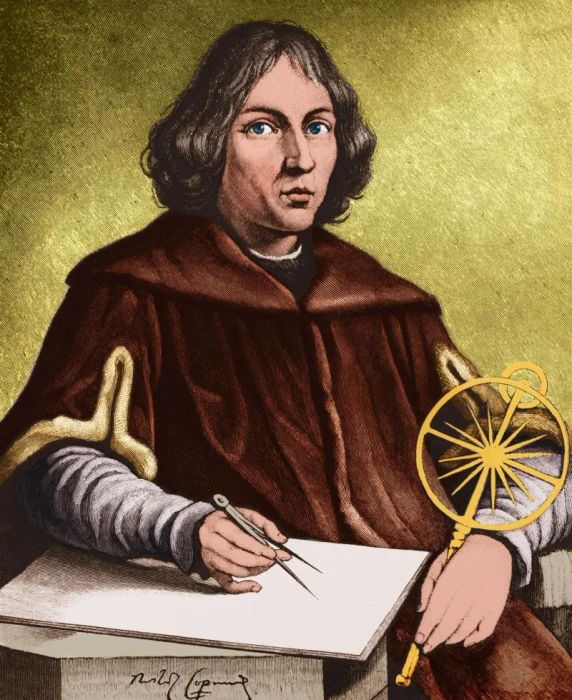

3. Saint Albertus Magnus

Saint Albertus Magnus was born around the year 1200 in the town of Lauingen, Bavaria. He was a monk, philosopher, scientist, bishop, and is also renowned as one of the 33 “Doctors” of the Catholic Church. Albertus wrote extensive works on a wide range of topics such as logic, theology, botany, geography, astronomy, astrology, mineralogy, chemistry, metaphysics, meteorology, zoology, physiology, and phrenology. He produced maps, charts, experimented with plants, studied chemical reactions, designed navigational tools, and conducted in-depth research on birds and animals. As a result, Saint Albertus Magnus is considered one of the greatest philosophers and thinkers of the Middle Ages.

In 1223, he joined the Dominican Order and was sent to a monastery in Cologne, where he remained throughout his academic career, writing, traveling, and teaching. While a student at the University of Paris, and later as a professor, Albertus developed a “new way of learning” based on Greek and Arabic philosophy and science, sparking unprecedented debates in the academic centers of Germany. He engaged in several writing projects that linked these ancient works with Christian teachings.

Albertus served as provincial of the German-speaking Dominican friars for four years, visiting over 56 monasteries, including one in Riga (now the capital of Latvia). He traveled on foot, often stopping to study natural phenomena, spending many hours in the libraries of the places he visited, copying any books that were new to him. As his fame grew, he was called upon to reconcile theological disputes, develop new curricula, organize conferences, and defend scientific learning. His diplomatic and arbitration skills made him an important figure in the church, even before he was appointed bishop of Regensburg in 1260, where he was tasked with revitalizing a diocese in both spiritual and financial decline. After three years of reforms and encouragement, he requested to be relieved of his post to return to teaching.

In addition to commenting on the scientific and philosophical works of classical thinkers, Albertus wrote numerous commentaries on the Scriptures and other theological works. His understanding of diverse philosophical texts enabled him to compile his own Summa Theologica. This foundational work argued that faith and reason are compatible sources of knowledge, inspiring the main work of his most famous student, and fellow Dominican, Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Albertus Magnus passed away on November 15, 1280, and was buried in Cologne. In 1931, he was canonized as a saint and declared a Doctor of the Church. Later, in 1941, he was named the patron saint of natural science. The greatness of Albertus lies not only in his devotion to Christian vision but also in his excellence in scholarship and intellectual breadth.

Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II was born around 1035 and became the head of the Catholic Church, ruling the papal territories from 1088 until his death. Urban II is known for initiating the First Crusade, which aimed to reclaim the Holy Land from the Turks. This marked the beginning of seven crusades that significantly impacted medieval history. Today, the effects of this crusade continue to shape the ongoing instability in the Middle East. Additionally, Pope Urban II restructured the leadership of the Church, forming an organized papal court system that has persisted and continues to influence the daily lives of many Catholics, as well as the Church's role in international politics. His legacy has been recognized by Pope Leo XIII, who declared him "Blessed" in 1881.

Urban II was a strategic thinker who sought to centralize the papacy in the heart of a unified Christian world, which was divided by internal conflicts. The Eastern and Western branches of the Church were in a state of division, and knights were fighting amongst themselves rather than against a common enemy. Urban II shifted the focus of hostilities elsewhere, aiming to recapture Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control. He used temporary authority and control over European armies to pursue his vision of unity. At the same time, he initiated internal reforms to make the Church more spiritual and to improve the behavior of its clergy. Urban II succeeded in enhancing the power of the papacy and uniting Europe after his crusade. However, in the long run, the ideals of the Crusades created tensions that tarnished Christianity’s image as a religion of peace. This conflict left an enduring rift between Catholicism and Islam, preventing the foundation of a more unified Europe. When the Crusades ended in failure, the focus of knights shifted back to defending their homelands.

The motivations behind Pope Urban II's actions are still debated among historians. Some believe that he sought unity between the Eastern and Western churches, which had been split since the Great Schism of 1054. Others argue that he saw this as an opportunity to solidify his legitimacy as pope, as he was competing with Pope Clement III at the time. A third hypothesis suggests that Urban II was responding to the threat of Islamic invasions in Europe, viewing the Crusades as a way to unite the Christian world in defense against this common enemy.

Before news of Jerusalem's capture by the Crusaders reached Italy on July 29, 1099, Pope Urban II passed away, unaware of the outcome. His successor, Pope Paschal II, established the modern Roman Curia, functioning as a royal court to govern the Church.

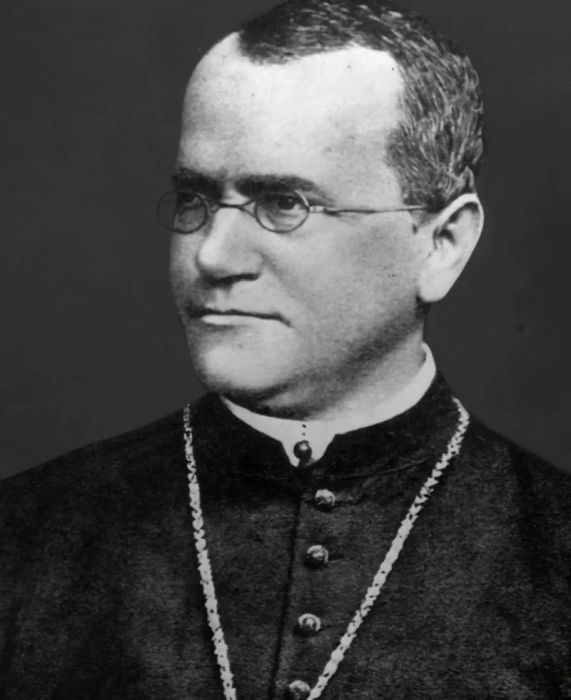

5. Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel was a teacher, priest, and scientist born in 1822 in the small village of Heinzendorf bei Odrau, now Hyncice, Czech Republic. His work in the field of genetics had a profound impact on the scientific world, though it is often said that its full potential was not realized during his lifetime. Nevertheless, Mendel's contributions are pivotal, as he was the first to establish the mathematical foundations of genetic science, which came to be known as 'Mendelianism.'

Raised in a poor family in rural Silesia, Mendel's academic abilities were recognized by a local priest, who persuaded his parents to send him to school at the age of 11. Mendel completed his studies at the Gymnasium in 1840 and later pursued a two-year program in philosophy at the University of Olmutz, Czech Republic, where he excelled in physics and mathematics. After completing his university education, Mendel entered the St. Thomas Augustine Monastery, which was a hub of culture and intellectual activity, exposing him to various teachings and new ideas that greatly influenced him.

In 1850, Mendel was sent to the University of Vienna for two years to study a new science curriculum. During this time, he focused on physics and mathematics, working under the guidance of Austrian physicist Christian Doppler and mathematical physicist Andreas von Ettinghausen. Mendel also studied plant anatomy and physiology, along with the use of microscopes, under the mentorship of botanist Franz Unger, who was passionate about cell theory.

In the summer of 1853, Mendel returned to the monastery and the following year began teaching there. He remained at the monastery until he was appointed parish priest 14 years later. His scientific endeavors largely ceased due to his extensive responsibilities at the monastery.

Gregor Mendel passed away on January 6, 1884, at the age of 61, from chronic nephritis. After his death, his successor burned all of Mendel's documents to end a dispute over taxes with the government. In 2021, his remains were exhumed, revealing details about his physical appearance, such as his height. Mendel's genome was also analyzed, revealing that he had a predisposition to heart issues.

6. Saint Ignatius of Loyola

Saint Ignatius of Loyola is proud to be recognized as the founder of the Society of Jesus, an order that has been credited with making the most significant contributions to 17th-century experimental physics. Their work extended to the development of the pendulum clock, speedometers, barometers, reflecting telescopes, and microscopes, as well as advancing knowledge in fields like magnetism, optics, and electricity. The Jesuits proposed hypotheses on the circulation of blood, the theoretical possibility of flight, the moon's influence on tides, and the wave nature of light. Their contributions to the study of earthquakes earned the recognition of seismology as the 'science of the Jesuits.' Despite these contributions, Ignatius originally founded the order with a focus on teaching and spreading Catholic doctrine, a mission they still uphold today.

Born in 1491 as one of 13 children in a noble family in northern Spain, Ignatius was deeply influenced by ideals of love and knighthood. From his early years as a Basque soldier, he transformed into a Catholic priest and theologian after a profound mystical experience convinced him he was called to serve Christ.

In 1521, Ignatius was severely injured in a battle against the French. During his recovery, he underwent a spiritual transformation. Reading the life of Jesus and the saints filled him with joy and ignited a desire to achieve great things. He recognized this feeling as divine guidance. Over time, Ignatius became an expert in the art of spiritual direction. Together with his companions, he founded the Society of Jesus to protect and spread the Church's message. Approved by Pope Paul III in 1540, he became the first Superior General of the order.

Ignatius passed away in 1556 and was canonized as Saint Ignatius of Loyola in 1622. By this time, his name had gained as much renown as the knightly heroes he admired in his youth. Today, schools, colleges, universities, and seminaries around the world continue to honor him, underscoring the vital role of education in advancing and protecting the Catholic Christian vision.

7. Priest Georges Lemaitre

The father of the Big Bang Theory, Priest Georges Lemaitre, was the first to propose the concept of an expanding universe. His groundbreaking research in astronomy and physics led him to derive what we now refer to as the 'Hubble's Law' and the 'Hubble Constant.' Lemaitre described his Big Bang Theory as the 'hypothesis of the primitive atom.'

There is no need to go into detail about the influence of this priest, as virtually everyone in the scientific community embraces his theory. Lemaitre was also among the first to apply computers in the study of cosmology and contributed to the development of the fast Fourier transform algorithm.

Priest Georges Lemaitre was born on July 17, 1894, in Charleroi, Belgium. He was a Catholic priest, astronomer, and physicist. As a young man, Lemaitre was drawn to both science and theology, but his studies were interrupted by World War I. He served as an artillery officer and witnessed the first gas attack in history. After the war, Lemaitre pursued theoretical physics and was appointed superior of his religious order in 1923. He also studied with renowned British astronomer Arthur Eddington and later traveled to the United States, visiting major cosmological research centers. He earned his Ph.D. in physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In 1925, at the age of 31, Lemaitre became a professor at the Catholic University of Louvain, a position he held through World War II. A dedicated teacher, he enjoyed working closely with students. His theory of the 'primitive atom,' explaining the origins of the universe, laid the foundation for what became known as the 'Big Bang Theory.' This groundbreaking idea was first published in 1931 and is now accepted by most astronomers. It marked a radical departure from the prevailing scientific views of the 1930s, where many astronomers were skeptical of the idea that the entire observable universe could have started with a single explosion. They were uncomfortable with the notion that the universe was expanding.

In addition to his scientific work, Lemaitre's religious devotion remained a significant part of his life. He served as president of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences from 1960 until his death in 1966.

On October 26, 2018, an electronic vote was held among all members of the International Astronomical Union. 78% of the votes supported renaming Hubble's Law to Hubble-Lemaitre Law in his honor.

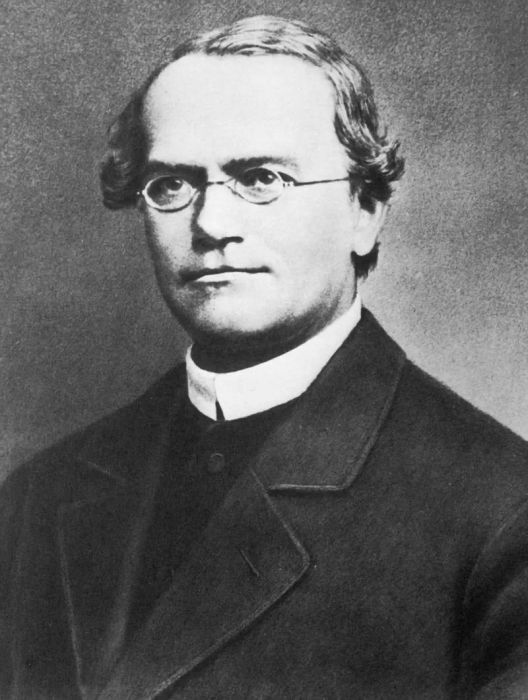

8. Saint Thomas Aquinas

Saint Thomas Aquinas was a humble friar who left his wealthy, noble family to join the Dominican Order in the 13th century. This quiet man rose to great heights in the fields of philosophy and theology, ensuring his name would never be forgotten. Aquinas' influence was so profound that he completely transformed philosophical thinking, paving the way for modern philosophers during the Enlightenment. His philosophy also impacted the natural sciences, including medicine. Moreover, this influence continues to be felt within the Roman Catholic Church, as his work 'Summa Theologica' remains a foundation for most seminary studies, shaping the thoughts of future priests who have, and will, affect the scientific world.

Saint Thomas Aquinas was born around 1224 in Roccasecca, Italy, into a noble family that had owned a castle for over a century. In his early years, Aquinas lived and studied at the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, founded by Saint Benedict of Nursia in the 6th century. He later attended the University of Naples and began his studies in theology there in the fall of 1239. During this time, he was encouraged to join a new religious order, the Dominican Order, founded by Saint Dominic of Guzman (1170–1221).

Recognizing his talent early, the Order sent Aquinas to study at the University of Paris for three years. By the age of 32, he was teaching there as a master of theology. The Dominican Order then brought Aquinas back to Italy, where he taught in Naples, Orvieto, and Rome from 1259 to 1268. It was during this time that he began composing his monumental 'Summa Theologica.' In December 1273, while preparing a dissertation on the sacraments for this work, Aquinas was called to serve as a theological advisor at the Second Council of Lyon. However, he passed away in Fossanova, Italy, on March 7, 1274, while en route to the council.

He was canonized as a saint in 1323, and in 1567, Pope Pius V declared him a Doctor of the Church. Through his deeply insightful and logically rigorous writings, Saint Thomas Aquinas continues to attract intellectual followers, not only among Catholics but also among Protestants and even those who are not Christian.