Art holds a unique power to connect with individuals on a deeply personal level. The interpretation of a piece of art can vary widely from one person to another, and both may differ entirely from the artist's original intent. Beyond its subjective meaning, art also carries rich narratives that unfold over decades or even centuries, waiting to be discovered by those who take the time to delve deeper.

10. The Arnolfini Portrait

The Arnolfini Portrait, created in 1434 by the Dutch master Jan van Eyck, is celebrated by art experts as one of history's most significant yet contentious works. Notably, the painting is executed in oil—a technique commonplace today but exceedingly uncommon in Western European art during the early 15th century.

This medium enabled Van Eyck to showcase his extraordinary attention to detail, a rarity in other artworks. Upon close inspection, the mirror on the back wall reveals a reflection of the entire room, including two additional figures near the doorway. (Interestingly, the dog is missing.) The artist even accounts for the distortion caused by the convex mirror. Remarkably, the tiny medallions within the mirror's frame illustrate scenes from the Passion of Christ.

The controversy surrounding the painting, however, lies not in the mirror but in the couple depicted. It was unconventional at the time to portray ordinary people in a domestic setting, leading historians to speculate about a hidden narrative. Some suggest the painting represents a newlywed couple, with the figures in the doorway serving as witnesses. This interpretation is debated, with scholars scrutinizing every detail—from the couple's hand gestures to the woman's hairstyle—to decipher their relationship.

9. Manneken Pis

When visiting Brussels, don’t miss the chance to greet one of Belgium’s most iconic landmarks, Manneken Pis (“Little Man Pee”). True to its name, it depicts a small boy urinating into a fountain, with historical records tracing its existence back to 1388. Originally a stone statue functioning as a public fountain, it was either lost or destroyed over time. The current Manneken Pis was crafted and placed by Flemish sculptor Jerome Duquesnoy in 1619.

Several legends surround the statue’s origins. The most popular recounts a young boy who saved Brussels during a siege by urinating on a fuse meant to detonate the city walls. Another tale suggests the statue represents Duke Godfrey III of Leuven as a toddler. During a battle, his troops allegedly hung him in a basket from a tree, where he urinated on the enemy, leading to their defeat.

Today, the statue is a major tourist draw, often seen wearing various outfits. This tradition began in the 18th century, and Manneken Pis now boasts a wardrobe of over 900 costumes, with new additions regularly.

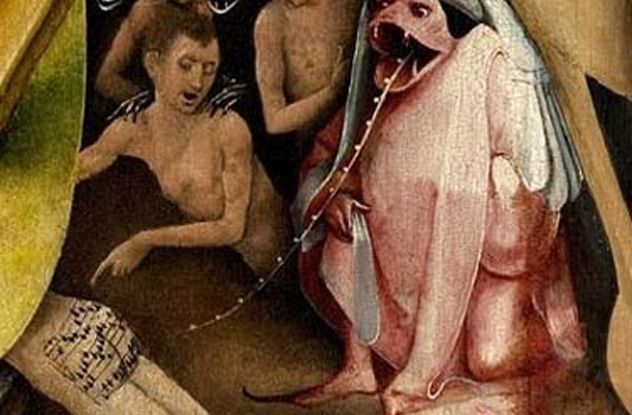

8. The Garden Of Earthly Delights

The Garden of Earthly Delights stands as one of the most intricate and visionary artworks ever created. Structured as a triptych, this masterpiece by the Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch was crafted between 1490 and 1510. The left section portrays Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, while the central panel bursts with a vibrant scene teeming with humans and animals engaged in diverse actions. The right panel, in stark contrast, unveils a grim, infernal landscape.

Initially, Bosch appears to illustrate the realms of heaven, Earth, and hell, perhaps as a cautionary tale against worldly temptations. This interpretation is widely accepted by art experts, yet the painting's elaborate and enigmatic details continue to reveal new insights even after six centuries. Notably, music is a recurring theme, with figures playing bizarrely fashioned instruments, such as flutes positioned between their buttocks. Researchers at Oxford have attempted to replicate these instruments, only to find they produce dreadful sounds.

The intrigue of Bosch's unconventional musical elements deepens with the recent discovery of sheet music etched onto a character's posterior in the hellish panel. This revelation led to the transcription and recording of what has been dubbed the “600-year-old melody from hell's behind.”

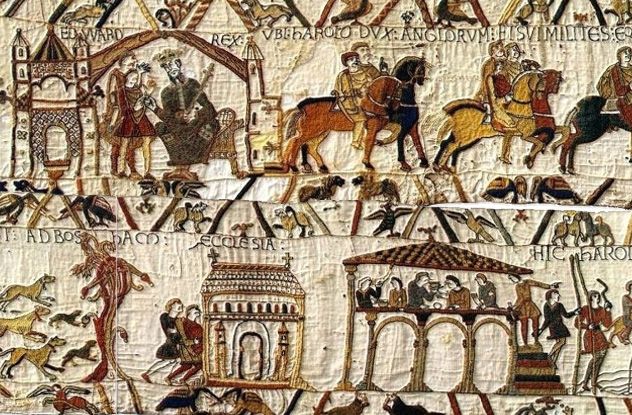

7. The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry stands as one of the most significant relics from the medieval era. This 70-meter (230 ft) embroidered cloth vividly illustrates 50 scenes chronicling the conflict between William the Conqueror and King Harold during the Norman conquest. Remarkably preserved despite its age of over 900 years, the tapestry is notably missing its concluding segment.

To be precise, the Bayeux Tapestry is not technically a tapestry. It is an embroidery, a distinct craft where threads are sewn onto a base fabric to create images, rather than being woven entirely on a loom.

The traditional tale suggesting that nuns across England created the tapestry and later assembled it is now considered improbable. Contemporary scholars argue that while the figures vary in appearance across scenes, the stitching methods remain uniform. This consistency suggests the work was likely produced by a group of highly skilled embroiderers.

The tapestry's origins remain its greatest enigma. While Bishop Odo, William’s brother, has long been considered the most probable patron, a newer hypothesis suggests it could have been commissioned by Edith Godwinson, the sister of the defeated Harold, to curry favor with the new ruler. Additionally, a historian has identified a monk named Scolland as a potential designer, as he appears to have depicted himself as a witness in one of the tapestry’s scenes.

6. Perseus With The Head Of Medusa

A visit to Florence’s Piazza della Signoria offers a breathtaking display of Renaissance artistry. The square boasts an impressive array of statues, including Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus, Giambologna’s The Rape of the Sabine Women, and the Medici lions. Yet, the most captivating piece is undoubtedly Cellini’s iconic Perseus with the Head of Medusa.

The artwork’s title speaks for itself. Cellini portrays a victorious Perseus holding Medusa’s severed head aloft, her lifeless form lying at his feet. This iconic scene from Greek mythology continues to captivate audiences today. Commissioned by Cosimo I de Medici upon his rise to grand duke, the statue was revealed to the public in 1554. Initially, Perseus stood alongside Michelangelo’s David, Donatello’s Judith and Holofernes, and the Hercules statue. While the latter two were moved to museums and replaced with replicas, the original Perseus has remained in the square for nearly 500 years, only temporarily covered during restorations.

Cellini left a unique signature on his masterpiece, beyond inscribing his name on Perseus’s sash. Observing the back of Perseus’s head reveals a face and beard formed by his helmet and hair. While not an exact match, many believe this to be a subtle self-portrait of Cellini.

5. Lenin Bust

A bust of Lenin might not seem extraordinary, as countless such statues have been erected worldwide over the last century. What makes this one remarkable is its location—Antarctica. More precisely, it stands at the pole of inaccessibility, the most isolated point in the South Pole.

During the Cold War, the Americans established a research station at the South Pole. Not to be outdone, the Soviets built their own station in 1958, deliberately choosing the most challenging location to reach. This move was purely a display of rivalry. After spending just a few weeks there, they left behind a bust of Lenin atop the chimney as a final gesture.

Over the following decade, several expeditions visited the station, with the last one occurring in 1967. For 40 years, the station and the bust were forgotten. In 2007, a Canadian-British team of explorers aimed to be the first to reach the pole of inaccessibility on foot. After a grueling 49-day journey, they arrived to find the only remaining structure—the Lenin bust—still standing, while everything else was buried under snow.

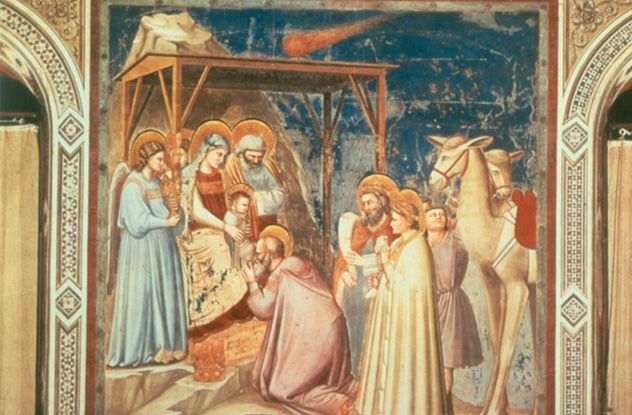

4. Adoration Of The Magi

The Adoration of the Magi depicts the well-known biblical episode where three wise men follow a star to present gifts to the infant Jesus. This scene has been a popular subject in art, with renowned artists like Botticelli, Rembrandt, Leonardo, and Rubens creating their interpretations. Among these, Giotto, a 13th-century Italian painter, stands out with his rendition of The Adoration of the Magi, regarded as one of his finest works. Notably, the Star of Bethlehem in his painting is believed by some to be inspired by Halley’s Comet.

The timeline supports this theory. Giotto completed the painting in 1305, having started it around 1303. Halley’s Comet was visible from Earth in 1301, making it plausible that Giotto witnessed it and drew inspiration. However, this wouldn’t be the first depiction of the comet, as the Bayeux Tapestry also illustrates its 1066 appearance, just months before the Norman Conquest. The European Space Agency was so convinced of the painting’s scientific significance that they named their Halley’s Comet mission “Giotto” in tribute to the artist.

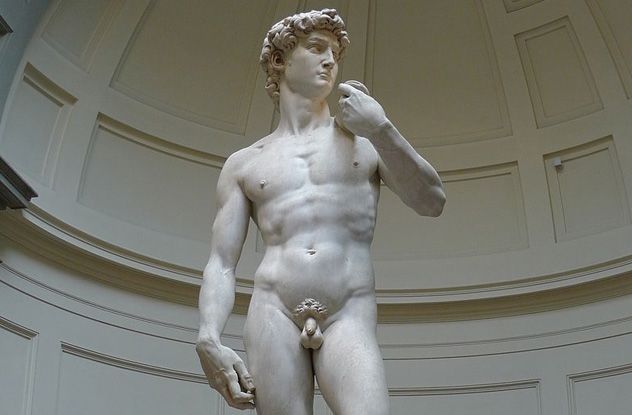

3. David

Michelangelo’s David is arguably the most iconic statue globally, yet few have the chance to gaze directly into his face. This is due to two reasons: the statue’s towering height of over 5 meters (17 ft) and its placement facing a column in Florence’s Galleria dell’Accademia, where it has stood since 1873.

Viewed from the side, as most see him, David exudes strength and confidence. However, a closer look reveals subtle hints of anxiety, aggression, and fear in his expression. Michelangelo’s deliberate choice of this expression suggests David is portrayed preparing to confront Goliath. This interpretation is supported by the claim that David holds a weapon, likely a fustibal, in his right hand.

Two Florentine physicians who studied David were amazed by the statue’s intricate details. The tension in his right leg, the furrowed brow, and the flared nostrils all align with the physical state of someone preparing to hurl a stone at an adversary.

This interpretation also addresses a frequently observed but seldom discussed feature of the statue—David’s modest anatomy. Italians often joke about David’s pisello, and many visitors wonder why Michelangelo gave him such understated proportions despite his otherwise imposing presence. However, anatomically, this detail is consistent with the physiological response of someone bracing for a life-or-death battle.

2. Rokeby Venus

Diego Velasquez, a prominent figure of the Spanish Golden Age, created the Rokeby Venus, regarded as one of his finest yet most contentious works. The painting features a nude Venus seated with her back to the viewer, gazing at the observer through a mirror.

While the painting’s eroticism is mild compared to other artworks of the time, its creation in 1651 coincided with the Spanish Inquisition’s strict regulations on nudity in art, which often led to fines, excommunication, or confiscation of works. Velasquez, protected by his patron King Philip IV of Spain, managed to avoid such consequences. This remains his only surviving depiction of a female nude.

The painting resided at Rokeby Park in England for nearly a century before moving to London’s National Gallery in 1906. It gained notoriety again in 1914 when suffragette Mary Richardson attacked it with an axe to protest Emmeline Pankhurst’s arrest. Despite seven deep slashes, the artwork was fully restored.

1. Declaration Of Independence

John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence is one of the most celebrated paintings in American history. Commissioned in 1817, it has adorned the US Capitol building for nearly two centuries and is even featured on the $2 bill.

Despite its name and significance, many mistakenly believe the painting depicts the signing of the Declaration of Independence. In truth, it portrays the five-member drafting committee, led by Thomas Jefferson and including Ben Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston, presenting the initial draft to John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress.

The artwork features 42 of the 56 individuals who ultimately signed the declaration. Trumbull aimed to include all 56 but lacked reliable references for the remaining 14. Additionally, certain architectural details of Independence Hall, where the event occurred, were inaccurately depicted, as they were based on a sketch Thomas Jefferson drew from memory.

At first glance, the painting seems to show Thomas Jefferson stepping on John Adams’s foot, leading some to interpret this as a nod to their political rivalry. However, a closer look reveals their feet are merely adjacent. To eliminate any confusion, the depiction on the $2 bill was adjusted to increase the distance between their feet.