In Edgar Allan Poe’s 1835 short story “Berenice,” the narrator raises a unsettling thought: “How is it that from beauty I have found a form of ugliness?” Imagine if the question were inverted: “How is it that from ugliness I have found a form of beauty?” Wouldn’t that make the inquiry even more unsettling?

This collection of 10 haunting artworks, each inspired by tragic events, provides a response to our question—and the answer is undeniably unsettling.

10. Ten Breaths: Tumbling Woman II by Eric Fischl

The title of Eric Fischl’s bronze sculpture, Ten Breaths: Tumbling Woman II (2007-2008), hints at its subject, but raises deeper questions. Why is the woman depicted nude? If she’s a gymnast, why isn’t she wearing attire? What explains the red-orange streaks on her earthy skin tones? Why is she falling, and what causes her awkward landing on her head, neck, and shoulder? These questions suggest Fischl’s work holds layers of meaning beyond its surface.

The mystery unravels when the painting’s origin is revealed. The plaque accompanying the statue states: “We watched in disbelief and helplessness on that brutal day. People we loved began falling, helpless and in shock.” “That brutal day” refers to September 11, 2001, when al-Qaeda launched a series of attacks on the United States.

During one of these attacks, terrorists flew two hijacked planes into the World Trade Center in New York City. In desperation, some individuals jumped from the upper floors to escape being consumed by flames. As noted by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the sculpture’s portrayal of “the fragility of the human body…gains profound meaning within this tragic context.”

9. The Raft of the Medusa by Theodore Gericault

Theodore Gericault’s oil painting The Raft of Medusa (1818-1819) depicts a pyramid of desperate figures, their anguish amplified by the towering wave looming over them. Some are clothed, others partially dressed, and a few completely naked, their lack of attire hinting at a frantic and sudden escape. The chaotic scene on the raft, a fragile refuge in stormy waters, suggests some passengers are already dead or dying. One body lies motionless on the planks, while another hangs halfway off the raft, submerged in the water.

As Dr. Claire Black McCoy notes, the painting’s subject, exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1819 and now housed in the Louvre, would have been familiar to its viewers. The July 1816 incident it portrays, recently covered in the news, became “a political scandal.” Officials aboard the French naval ship Medusa, including the governor of Senegal and his family, were en route to secure the colony and maintain the clandestine slave trade, despite France’s official abolition of slavery. The captain accidentally grounded the ship on a sandbar off West Africa, leading to the tragic events depicted.

After the ship’s carpenter failed to fix the damage, the governor, his family, and other high-ranking individuals secured spots on the six lifeboats. The remaining 150 passengers were abandoned on a makeshift raft built from the ship’s masts. Only fifteen were rescued, and just ten lived to recount the harrowing tale of cannibalism, murder, and other atrocities they endured on the raft.

8. Grey Day by George Grosz

George Grosz’s artwork often appears to depict mundane moments from daily life. Yet, the grotesque nature of his portraits, a hallmark of his style, suggests deeper, darker undertones. His post-World War I piece Grey Day (1921) exemplifies this. A laborer with a shovel hurries past a factory with a smoking chimney, while a businessman approaches the viewer, walking down a narrow sidewalk beside a building.

Ahead of them, a grim, scarred, one-armed veteran in uniform walks with a cane. Between him and the figure in front stands a partially built brick wall. The figure ahead is a wealthy, cross-eyed man striding confidently in the opposite direction. Dressed in an expensive suit, he carries a briefcase and an L-shaped ruler, hinting at his profession as a carpenter or engineer. Despite his respectable appearance, his crossed eyes and the scars on his egg-shaped head suggest he, too, has endured violence.

As noted by the Tate, a British art institution, Grosz’s painting “highlights how the wealthy prospered from war, while disabled veterans were left impoverished and alienated from society.” This division is symbolized by the partially constructed wall separating “the two groups.” The Tate article adds that the wall’s ambiguity forces “the viewer to decide whether it is being built or torn down.”

7. Big Electric Chair by Andy Warhol

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed by electrocution on June 19, 1953, after being convicted of espionage against the United States. While Julius died swiftly after a single shock, Ethel endured three applications of electricity before the fourth finally ended her life, causing a “ghastly plume of smoke [to rise] from her head.” As Irene Philipson writes in Ethel Rosenberg: Beyond the Myths, Ethel’s death was far more agonizing than her husband’s.

Andy Warhol revolutionized art with silkscreen painting, a technique enabling “the artist to transform photographs into multiple, ‘mass-produced’ works.” Initially, he used this method to create images of celebrities and mundane objects. Later, his focus shifted to darker themes in his Death and Disasters series.

One of these works, Big Electric Chair (1967-1968), was based on a press photo of the execution chamber at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, where the Rosenbergs were killed. Warhol’s unsettling series may have aimed to numb viewers to the grim realities his art portrayed. “When you see a horrific image repeatedly,” he argued, “it loses its impact.”

6. Guernica by Pablo Picasso

A bull, a horse, dismembered bodies, horrified faces, a shattered sword gripped by a dying man, and a woman in anguish—these are among the haunting images in Pablo Picasso’s nightmarish Guernica (1937). As detailed on a website dedicated to the artist, this commissioned piece captures Picasso’s visceral response to the Nazis’ brutal bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

The mural, rendered in black, blue, and white oils, blends pastoral and epic styles to depict “the horrors of war and the suffering it imposes on individuals, especially innocent civilians.” The absence of color conveys the “harsh reality of the bombing’s aftermath.” While interpretations vary, the raging bull is often seen as a symbol of fascism, and the horse represents the people of Guernica, a Republican stronghold opposing Francisco Franco’s Nationalists.

5. The Course of Empire: Destruction by Thomas Cole

For centuries, beginning in 27 BC, the Roman Empire dominated the Western world. While not a utopia, it provided law, order, and protection across much of the Middle East and Europe. During the Pax Romana, or “Roman Peace,” which lasted around 200 years, art and culture thrived. To its citizens, the Empire seemed eternal. Yet, when Rome fell to barbarian invaders, it must have felt as though life itself had ended, as their world was irrevocably altered.

This monumental collapse inspired numerous artworks, including Thomas Cole’s The Course of Empire: Destruction (1836), which vividly portrays this historic event. Housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the painting depicts armies clashing in a stormy battle, with the city ablaze in the background. A fleet of enemy ships (oddly resembling Viking vessels) attacks the defenders, with one ship bridging a gap in a collapsing bridge. Roman soldiers make a desperate last stand on rooftops and steps, fighting to the end.

Despite a sinking ship, it’s evident the invaders have triumphed. Many Roman soldiers lie dead or dying, and the city burns in the background. At the edge of a rooftop, a barbarian seizes a terrified Roman woman moments before she attempts to leap into the sea. A colossal statue of a Roman soldier, charging forward with a raised shield, symbolizes the legion’s defeat and Rome’s impending collapse—its shattered head lies broken on the rooftop below. The panoramic painting captures the sweeping devastation that has engulfed the Empire and its people.

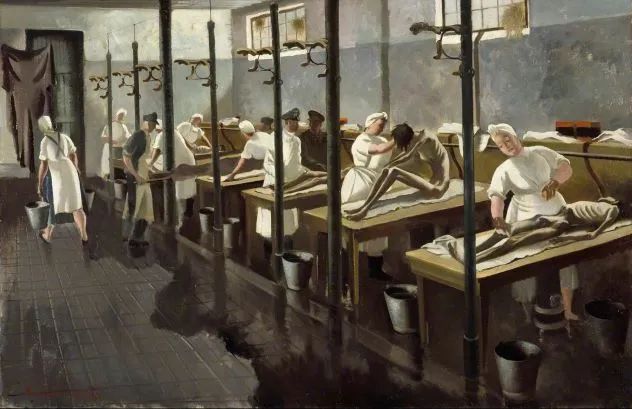

4. Human Laundry by Doris Clare Zinkeisen

The Nazis’ dehumanization of Jews is starkly conveyed in Clare Zinkeisen’s 1945 painting Human Laundry: Belsen, 1945, housed in the Imperial War Museum in London. Rendered in grays and whites, the artwork depicts skeletal figures laid out on rough tables. German nurses, overseen by a military doctor, wash the prisoners with soap and water from buckets at the tables’ ends. A pair of bearers arrives with another covered body, either delivering or removing a victim of the Belsen concentration camp’s horrors.

As notes on the painting explain, “Zinkeisen highlights the stark contrast between the well-fed, robust German medical staff and the emaciated bodies of their patients.” This effect is intensified by the nurses’ indifferent expressions as they work, the prisoners’ resigned and faceless postures, and a nurse casually carrying buckets past a puddle of spilled water. The medics, from a nearby German military hospital, were tasked with washing and delousing prisoners to prevent typhus before transferring them to a makeshift Red Cross hospital.

Additional notes shed light on the plight of World War II prisoners and the painting’s theme: “The ‘human laundry’ comprised around twenty beds in a stable where German nurses and captured soldiers shaved inmates, bathed them, and applied anti-louse powder before transferring them to a makeshift Red Cross hospital.”(LINK 9)

3. The Broken Column by Frida Kahlo

Not all disasters are criminal, war-related, social, or political, nor do they always impact entire communities or nations. Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s tragedy was personal and accidental, yet it became the driving force behind most of her artistic work. Her paintings predominantly reflect her physical pain, disabilities, and their profound impact on her personal life.

Kahlo, who contracted polio as a child, narrowly survived a bus accident in her teens. The crash left her with a fractured spine, collarbone, ribs, a shattered pelvis, a broken foot, and a dislocated shoulder. Shortly after this life-altering event, Kahlo turned to painting as a means of coping with her suffering, which persisted throughout her life. As a website dedicated to her explains, “From the start of her recovery, she immersed herself in painting while confined to a body cast.” Despite undergoing 30 surgeries, she continued to create deeply personal, often symbolic self-portraits.

The Broken Column, a 1944 self-portrait, depicts Kahlo topless, her arms at her sides, tears streaming down her face as she gazes at the viewer. A sheet drapes her hips, and an orthopedic corset with straps binds her torso. A large fissure splits her body, revealing a broken column in place of her spine. Art historian Andrea Kettenmann, author of Kahlo, describes the fissure as a symbol “of the artist’s pain and loneliness.” Nails piercing her face and body further emphasize her suffering. As Kettenmann notes about another of Kahlo’s works, The Landscape (1946-1947), the same applies to The Broken Column: “The barren, cracked landscape [mirroring Kahlo’s broken body] serves as the backdrop for her art.”

2. The Price by Tom Lea

The Price (1944) is a stark, visceral depiction of the sacrifices made by soldiers on the World War II battlefield. A U.S. Marine, advancing through the smoke-filled terrain of Peleliu in 1944, appears to stumble. His left face, shoulder, chest, and arm are torn apart, drenched in bright red blood. The artist, Tom Lea, described the scene: “He was struck by a mortar blast, staggered a few steps, and collapsed.” After the war, the painting hung outside Eisenhower’s Pentagon office as a sobering reminder of “the cost of war.”

Adair Margo, a gallery owner and friend of the El Paso-based artist, remarked, “Lea was the only war artist who witnessed and depicted live combat, showing U.S. soldiers being torn apart, with blood and gore scattered across the ground.” Margo emphasized that Lea’s work offers an unflinching, honest portrayal of war’s brutal reality, both then and now. She added that Life magazine sent Lea to the frontlines because he “could capture battle scenes in color, unlike black-and-white photography,” and had the ability to “piece together fragments of combat to convey the full intensity of war.”

Larry Decuers, curator of The National World War II Museum in El Paso, noted that the exhibit featured 26 of Lea’s paintings from the U.S. Army’s art collection, on loan from the U.S. Army Center of Military History. These works, originally published in Life magazine during the war, provided readers with an unfiltered view of the conflict. During the U.S. assault on Peleliu, where Japanese forces were deeply entrenched, 1,100 Marines lost their lives, 5,000 were wounded, and nearly all 11,000 Japanese defenders perished.”

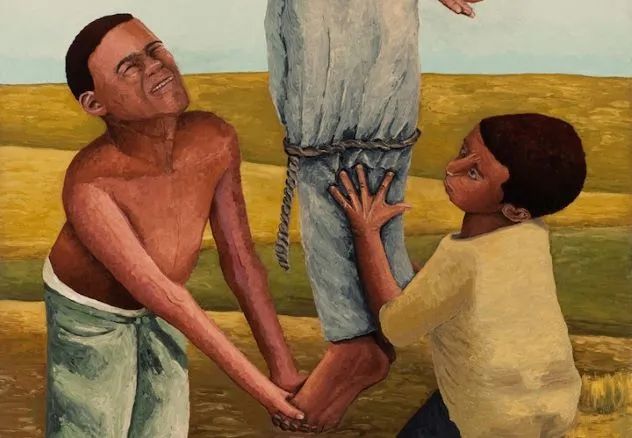

1. Stories Behind the Postcards by Jennifer Scott

Jennifer Scott’s 2009 series, Stories Behind the Postcards, was showcased at America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Inspired by souvenir postcards that, as the museum’s website notes, “featured images of lynchings and were circulated nationwide,” Scott’s work reflects on the era between the 1880s and World War II. Viewing these postcards, she pondered the unseen aspects: “the families who had to retrieve the victims, mourn their loss, and bury what little remained.”

Scott aimed to evoke empathy for the victims, urging viewers to “imagine their lives before their deaths were immortalized on postcards.” She also sought to challenge viewers to move beyond superficial understandings of race and race relations, hoping her work would inspire deeper reflection and leave a lasting impression on future generations.

In three of her paintings—Three Generations, The Impossible (pictured), and My Son, My Grandson—Scott used vibrant colors, unlike the black-and-white or sepia tones of the original postcards. She explained that color prevents viewers from distancing themselves from the harrowing scenes, reminding them that “these atrocities occurred in the midst of nature’s beauty, often in broad daylight.” Three Generations depicts a middle-aged woman consoling an older woman overcome with grief and rage as she leans over the body of a young woman lynched after being raped.