Magicians abide by an unspoken code: never disclose the method behind their illusions. So, when a 2004 exhibition revealed the secrets of Harry Houdini’s tricks, it caused a stir within the magic community. David Copperfield denounced it as a violation of magic ethics, and many magicians vowed to boycott the event. Numerous performers admitted they still relied on Houdini’s methods.

But with Houdini having passed nearly 90 years ago, many modern magicians no longer rely on his outdated techniques. In fact, his secrets had been exposed long before, with his team beginning to disclose them just three years after his death.

This list is for those who are eager to uncover Houdini’s secrets. If you’re not interested, it’s best to stop reading now.

10. The Radio Of 1950

Houdini created the “Radio of 1950” illusion for his evening performances from 1925 until his death the following year. The radio itself was a cutting-edge novelty at the time, and the act showcased what Houdini imagined the radio would be like in 1950.

According to Dorothy Young, Houdini’s assistant, the magician began by presenting a large table covered with a cloth that hung down halfway to the floor. Houdini circled the table, lifting the cloth to demonstrate that there were no mirrors or hidden objects underneath.

Next, assistants positioned a massive radio on the table, measuring about 2 meters (6 ft) long and 1 meter (3 ft) tall and wide. The radio featured oversized dials and large double doors at the front. Houdini opened the doors to reveal only coils, transformers, and vacuum tubes inside, before closing them again.

Houdini adjusted the dial until a radio station was clearly tuned in. The announcer’s voice came through, saying, 'And now, Dorothy Young, performing the Charleston.' Without warning, the radio top flew off, and a young assistant popped out, leaping down to dance the Charleston.

'Tune into any station and you'll get the girl you want,' Houdini declared. 'But no, gentlemen, it's not for sale.'

The Secret: The trick relied on a unique table, a 'bellows' table, which had two table tops. The top one featured a trapdoor that opened upward. The lower top was suspended by springs, allowing it to drop under Ms. Young’s weight while remaining concealed beneath the tablecloth.

Young was hidden inside the radio when it was placed on the table. She opened the trapdoor and slid into the bellows section between the two table tops, waiting there as Houdini demonstrated the radio’s supposed emptiness. While adjusting the station, she quietly climbed back into the radio.

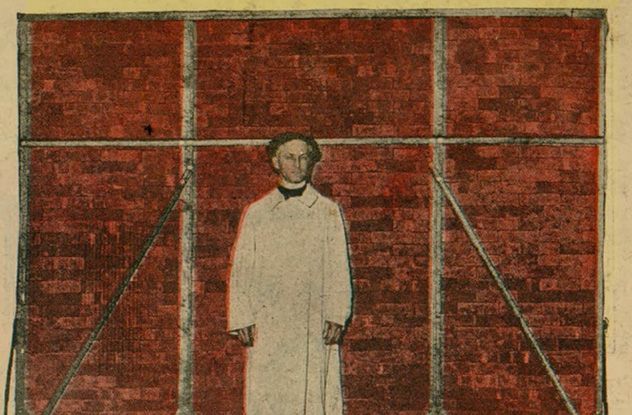

The image above shows Houdini's younger brother, Theodore 'Dash' Hardeen, performing the radio illusion with his assistant Gladys Hardeen. Hardeen bought the radio from his brother’s estate. Dorothy Young lived to be 103 and passed away in 2011.

9. Metamorphosis

At the end of his career, Houdini performed the iconic 'Radio of 1950' illusion. However, in the early days of his career, he and his wife Bessie captivated audiences with the 'Metamorphosis' illusion, first performed in 1894. While Houdini did not invent the trick, it was a significant innovation compared to earlier acts that featured two men switching places. Houdini and his wife exchanged positions instead, and their version caught the attention of the Welsh Brothers Circus, leading to a tour in 1895.

The 'Metamorphosis' illusion itself was quite intricate. Houdini’s hands were securely bound behind his back, and he was placed inside a sack that was tightly knotted. This sack was then placed in a locked and strapped box, which was further enclosed within a cabinet, obscured by a curtain.

Bessie entered the cabinet and drew the curtain closed behind her. She clapped her hands three times, and on the third clap, Houdini revealed the curtain to show that Bessie had vanished. Astonishingly, she was found inside the sack, in the locked box, her hands still bound and all straps and locks intact.

The Secret: The key to this illusion was remarkably straightforward: relentless practice. Houdini was a master of ropes and knots, and the knot used to bind his hands was one that he could easily slip out of. By the time the sack was draped over his head, his hands were already free. The sack featured eyelets along the top, allowing Houdini to feed a rope through and loosen it by pulling from the inside.

After Houdini was placed inside the box, he quickly escaped from the sack while Bessie locked and secured the box’s lid. Once the curtain was drawn by Bessie, Houdini slipped through a hidden rear panel in the box. Contrary to what the audience assumed, it was Houdini who clapped, not Bessie. He clapped once and then assisted Bessie in climbing into the box through the rear panel, all while ensuring the locks and straps remained undisturbed.

On the third clap, Houdini opened the curtain. As he unlocked and unstrapped the box, Bessie, who was inside, wriggled into the sack and tied the ropes around her wrists. Through rigorous practice, Harry and Bessie perfected the trick, allowing Houdini to escape and Bessie to take his place in just three seconds.

8. The Hanging Straitjacket Escape

The inception of this act was driven by sibling rivalry. Houdini’s younger brother, Hardeen, had his own act, and both brothers performed escapes from straitjackets behind screens. When an audience requested that Hardeen perform the escape in full view, he agreed and earned a standing ovation. When Hardeen shared this with Houdini, Harry decided to outdo him by creating the Hanging Straitjacket Escape. He often performed this act a few hours before his evening shows to draw a bigger audience.

Houdini typically performed this daring escape in front of a large crowd on the street. He was strapped into a straitjacket and his ankles bound. A crane then lifted him high, allowing the audience to see what he did firsthand, reinforcing the idea that there was no trick involved in the feat.

The Secret: In his 1910 book Handcuff Escapes, Houdini himself disclosed the secrets behind his straitjacket escapes. The primary trick was to create slack in the jacket as it was being strapped on.

As the straitjacket was draped over his arms, Houdini ensured his arms were crossed—not folded—across his chest, with his dominant right arm on top. As the jacket wrapped around his back, Houdini pinched the fabric and pulled outward to loosen material around his chest. When the jacket was tightened, he retained control over the slack, and as the jacket was buckled in place, Houdini took a deep breath, expanding his chest. This gave him a fair amount of wiggle room in the front.

When suspended upside down, Houdini used his stronger arm to force his weaker (left) elbow outward, away from his body. This movement stretched the slack around his right shoulder, enabling Houdini to pull his right arm over his head. Being upside down was an advantage, as he used gravity to assist in pulling the arm free.

“Once having freed your arms to such an extent as to get them in front of your body,” Houdini wrote, “you can now undo the buckles and the straps of the cuffs with your teeth.” Once the cuffs were released, Houdini unbuckled the neck, top, and bottom straps. With these undone, he slipped his arms free and wriggled out of the jacket. Contrary to popular belief, dislocating the shoulder was not usually necessary, and Houdini only resorted to it as a last measure.

Houdini became so skilled in this escape that he reduced the time needed from half an hour to just three minutes. For those times when a special straitjacket was used, Houdini wasn’t above palming a tool to cut the straps and buckles.

7. The East Indian Needle Trick

The exact origins of the illusion known as the 'East Indian Needle Trick' remain a mystery, but the name seems fitting. The earliest magician on record to perform the trick was a Hindu of unknown origin named Ramo Sami (or Samee), who toured America in 1820. It is believed that Houdini revived this illusion from circus sideshows as early as 1899, incorporating it into his stage act, where it became a key feature throughout his career.

Houdini would have a spectator examine between 50 to 100 needles and 18 meters (60 feet) of thread. The same spectator would then inspect Houdini's mouth. Afterward, the magician would swallow both the needles and thread simultaneously, followed by a sip of water. Moments later, Houdini would regurgitate them, unwinding the thread and revealing the needles suspended from it.

The Secret: Three years after Houdini’s death, his prop engineer, R.D. Adams, disclosed the secret of the trick. Houdini placed a packet of thread, with needles already attached, between his cheek and teeth. The needles were threaded with knots before and after them, preventing them from coming loose inside Houdini’s mouth. The knots allowed the needles to shift naturally along the thread. The entire thread and needles were then rolled into a flattened packet and discreetly inserted into Houdini's mouth, similar to how a tobacco plug would be placed.

When Houdini allowed a spectator to inspect his mouth, he pulled back his upper and lower lips from his gums and teeth using his fingers. These fingers naturally curled into the cheeks, providing cover for the hidden packet. If the spectator insisted that he move his fingers, Houdini would simply shift the packet beneath his tongue.

Houdini then positioned the loose needles and thread on his tongue and acted as though he was swallowing them with a sip of water. In actuality, he spat the needles and thread into the water glass, ensuring enough liquid remained to obscure the objects. If the spectator remained close, Houdini would discreetly place the needles under his tongue and hold them there until the trick’s conclusion. At the end, he would drink again, spit out the needles, and quickly pass the glass to an assistant. Finally, Houdini unwound the packet of needles from his mouth.

Houdini also performed a variant of this trick involving razor blades. He kept a packet of pre-threaded blades hidden in a fold of a handkerchief. On the same handkerchief, he displayed loose blades for the spectator’s inspection. When he appeared to place the loose blades in his mouth, he actually placed the packet instead. He would then hand the kerchief, with the loose blades, to an assistant while he completed the trick.

The image above is almost certainly a staged promotional photo. The needles visible in the image are far too large for Houdini to conceal in his mouth.

6. Walking Through A Brick Wall

Houdini showcased this particular illusion on only a few occasions during a week-long performance in New York City in July 1914, but it left a lasting impression on those who witnessed it.

While Houdini performed his other acts, workers built a 3-meter (9 ft) high and -meter (10 ft) wide wall on stage, positioned in front of the audience to allow them to view both sides. The structure was placed on top of a large muslin carpet, allegedly to prevent any trap doors from being used. When the wall was complete, Houdini invited the audience to use a hammer to test its solidity.

Once the audience settled back into their seats, Houdini positioned himself on one side of the wall, while a screen was moved in front of him. A second screen was placed on the opposite side. Moments later, both screens were swiftly removed, revealing Houdini standing on the other side of the wall. According to the press: “The audience remained utterly speechless for nearly two minutes after the feat was completed. They were too dumbfounded to applaud.”

The Secret: The trick lay in the rug. Far from hindering the use of a trap door, it actually aided in its function. The trap itself was long and spanned both sides of the wall. Once triggered, the carpet or cloth formed a V-shaped hammock, allowing Houdini to crawl underneath the wall.

As per R.D. Adams, Houdini also performed a variation of this illusion. In this version, a solid glass plate was placed beneath the brick wall, preventing the use of a trap door. Several assistants, dressed in plain work attire, wheeled a screen in front of Houdini. After it concealed him, he swiftly changed into the same work clothes and walked with the assistants to position a second screen on the opposite side. Behind this second screen, Houdini quickly changed back into his stage costume. Meanwhile, mechanical hands behind the first screen waved to mislead the audience into thinking Houdini was still hidden there. Moments later, both screens were removed, unveiling Houdini on the other side.

Houdini passed the illusion on to his brother Hardeen to include in his act. Many have speculated that Houdini abandoned the trick because it was not originally his. He had bought it from another magician—or even stole it, according to some rivals. The controversy, along with the widespread knowledge of the trick’s secret, likely made it too dangerous for Houdini to continue performing it.

5. The Mirror Handcuff Challenge

One of Houdini’s earliest performances involved advertising that he could escape from any handcuffs, whether provided by the audience or local law enforcement. His handcuff act caught the attention of theater manager Martin Beck, and in 1899, Beck gave Houdini his first major opportunity to tour vaudeville stages.

The Secret: There wasn’t just one secret to Houdini’s handcuff escapes. He dedicated his life to studying locks and possessed a vast, encyclopedic knowledge of handcuffs. He could inspect a pair of cuffs and instantly know what type of key was required. Houdini would then hide that key on his person. Later in his career, he developed a flexible steel belt, which rotated on ball bearings with the flick of his elbow. The belt had multiple compartments containing various keys and picks.

Some handcuffs didn’t even need a key to open. In 1902, Houdini revealed that certain cuffs could be unlocked by striking them against a hard surface. When Houdini visited a new town, he often investigated the handcuffs used by local police. In his book Handcuff Secrets, he demonstrated how a loop of string could be used to remove a screw from a cuff’s lock.

At times, Houdini had to escape from what were known as freak handcuffs—unique cuffs with only one key to unlock them. In these cases, he insisted on testing the key first. While Houdini pretended to struggle with the cuffs, an assistant would go backstage and search Houdini’s vast collection of keys for one that resembled the freak key. The assistant would then pass off a fake key to Houdini, who would return it to the owner while secretly keeping the real one.

Houdini wasn’t above using specially designed handcuffs. During his famous bridge jumps into rivers with his hands shackled, he often used what were known as “jumpcuffs.” These cuffs had a deliberately weak interior spring and easily passed inspection. As soon as Houdini hit the water, a simple flick of his wrist would release the cuffs.

Houdini was only ever truly stumped by handcuffs twice. The first instance occurred in Blackburn, England, where he was bound by exercise trainer and future author William Hope Hodgson. Hodgson secured Houdini so tightly that it took the magician an hour and 40 minutes to escape, leaving him with bloody welts.

The second time was in London, where the Daily Mirror took up Houdini’s challenge. A reporter from Mirror found a blacksmith from Birmingham who had spent five years creating cuffs that were supposedly impossible to pick. The “Mirror Cuff” featured a series of nested Bramah locks. Houdini managed to escape after an hour and 10 minutes. Some experts argue that the entire “Mirror Cuff” escape was staged, claiming Houdini had a duplicate key hidden all along. They suggest that he deliberately took 70 minutes to unlock the cuffs for dramatic effect.

4. The Milk Can Escape

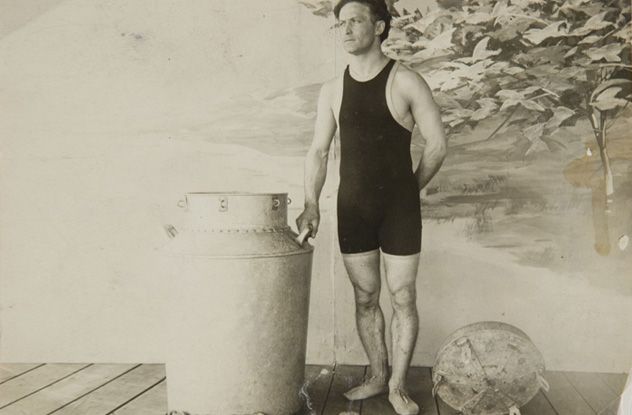

Houdini began one of his simplest yet most compelling acts in 1901. Due to his remarkable presentation, it became one of his most famous and mesmerizing illusions. Advertisements for the escape ominously warned that “failure means a drowning death.” He later described it as “the best escape that I have ever devised.”

Houdini invited the audience to inspect his milk can, encouraging them to kick it to test its sturdiness. The can stood about 1 meter (3 ft) tall, and the lid was secured with six hasps that slid over six eyelets on the can’s collar. The audience then filled the can with water while Houdini changed into a bathing suit. Upon his return, he challenged the audience to time how long they could hold their breath, with few able to last more than 60 seconds. Smiling, Houdini climbed into the milk can, causing excess water to spill out.

Once the lid was placed on the can, Houdini had no choice but to submerge his head. The six hasps were locked into place, and locks—sometimes provided by the spectators—were fastened to the eyelets. By this point, Houdini had already been underwater for at least a minute. A screen was placed around the can. Two agonizing minutes later, Houdini emerged, dripping wet and gasping for breath, while the locks on the can’s lid remained intact.

The Secret: Years after his death, a friend of Houdini disclosed the secret: The collar was not actually riveted to the can. The milk can’s simple construction made it seem secure, but the collar rivets were fake. Since the collar was tapered and greased, anyone inspecting the milk can couldn’t pull off or even move the collar. However, someone inside could easily push the collar upwards and climb out without disturbing the locks.

3. Chinese Water Torture Cell

Unlike Houdini’s elephant cabinet, the Chinese Water Torture Cell still survives, and its mechanics are well understood. The legendary magician had the cell specially crafted for $10,000 and patented it.

Shaped like an oblong aquarium laid on its side, the cell featured a mahogany and nickel-plated steel frame with brass plumbing fixtures. It was 67 centimeters (26.5 in) wide and 150 centimeters (59 in) tall, weighing 3,000 kilograms (7,000 lb) and capable of holding 950 liters (250 gal) of water. The glass front plate was 1.5 centimeters (0.5 in) thick and tempered. The cell could be disassembled into three crates and four cases, and Houdini always carried a backup cell in case the first one malfunctioned.

Houdini started the illusion by inviting a spectator to choose any spot on the stage. The cell was then moved to the chosen location, proving that no trap door was involved. As shown in the video above, Houdini allowed the spectator to examine the cell and offered $1,000 if they could demonstrate how he could breathe while inside.

Next, Houdini lay on his back, and assistants placed his feet into mahogany stocks. Pulley systems lifted him upside down, lowering him head-first into the tank. The stocks acted as a lid, secured with four hasps and padlocks. Drapes were drawn over the tank, and an assistant stood nearby with an axe, prepared to smash the glass if something went wrong. The orchestra played “Asleep in the Deep.” Two minutes later, Houdini reappeared behind the curtain. The stocks remained atop the tank, the locks still intact.

The Secret: Two elements were essential to the illusion’s success. First, the stocks were set deeply. When Houdini was submerged in the tank, some of the water overflowed, creating a small pocket of air between the water’s surface and the stocks.

Secondly, the mahogany boards that made up the sides of the ankle stocks separated slightly when the hasps were locked. After the curtain was drawn, Houdini pushed his feet upward using the tank’s sides, twisted sideways, and pulled his feet through the widened gaps in the stocks. He then drew his legs in, flipped around, and breathed in the air pocket.

The two boards of the stock were also hinged to open, and Houdini climbed out, closed the boards, and reappeared before the audience.

An urban legend suggests Houdini drowned in the cell, but this is false. He passed away in a hospital from an infection caused by a ruptured appendix. He had only one incident during this performance: on October 11, 1926, a loose cable caused the pulley to malfunction, shifting the stocks and fracturing Houdini’s ankle.

2. The Vanishing Elephant

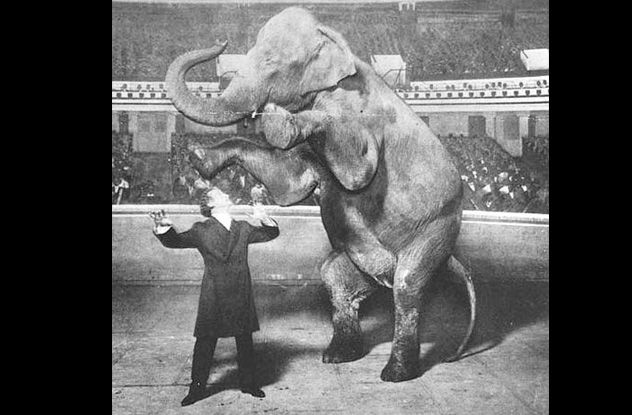

On January 7, 1918, Houdini performed his most famous illusion, the Vanishing Elephant, at New York’s Hippodrome Theater, the world’s largest stage at the time. He led an elephant into a large cabinet, and, in an instant, it vanished. The mystery behind this trick, second only to the Chinese Water Torture Cell, has intrigued audiences ever since.

The cabinet vanished, and with it, the secret to Houdini’s illusion. Since it was performed only once, little information was available. Contemporary newspaper articles about the performance are no longer available, and for years, the method behind the Vanishing Elephant was thought to be lost to time.

The Secret: To understand the illusion, we must first look at the Hippodrome stage. Although the theater no longer stands, photographs reveal it to be a vast venue with 5,697 seats spread across three semicircular tiers. No audience member had a perfect line of sight to the elephant’s cabinet, which was placed far from the stage's edge, helping to maintain the mystery of the trick.

The appearance of the cabinet has been a matter of debate. R.D. Adams suggested it was nothing more than a cage-like structure. According to Adams, the lower section of the frame concealed a roll of cloth identical to the curtains at the rear. The cloth was connected to a roller via wires, and the roller was equipped with a spring so powerful that it required two men to wind it. At the crucial moment, Houdini fired a gun, prompting the audience to blink. As they blinked, the roller swiftly pulled the cloth up in front of the elephant, creating the illusion that it vanished instantly.

Another description of the elephant cabinet portrays it as being oblong, mounted on wheels, with double doors on one end and a large curtain on the other. The rear doors featured a circular opening in the center, allowing limited light to penetrate inside. After the elephant and its trainer entered, the curtain was drawn, and several assistants gradually turned the cabinet. Meanwhile, the trainer shifted the elephant to the back, and a black curtain was draped over both of them. When Houdini opened the front curtain, he turned the cabinet once more, preventing the audience from seeing the interior for any extended period. All they could perceive was the circular light from the back and a darkened interior, with the elephant seemingly gone.

1. The Underwater Box Escape

Houdini’s career saw a consistent advancement in the difficulty of his escapes. As handcuff escapes became monotonous, he progressed to jail escapes. In 1907, he performed escapes by jumping from bridges while handcuffed. By 1908, he introduced the Milk Can Escape. Finally, in 1912, he showcased his Underwater Box Escape. That same year, he also introduced his most famous escape: the Chinese Water Torture Cell.

Houdini’s first Underwater Box Escape occurred off the side of a barge in New York’s East River. He was handcuffed and climbed into a wooden crate, which was then nailed shut, bound with trusses, and chained. The crate was lowered into the river, where it sank, and 150 seconds later, Houdini emerged on the surface a short distance away. Scientific American magazine hailed it as 'one of the most remarkable tricks ever performed.'

The Secret: The secret, naturally, lay in the design of the crate. The crate featured small holes to allow Houdini to breathe while waiting for the box to be nailed, trussed, and chained. These holes also helped the crate to sink. Additionally, the crate was square, with four boards on each side. On one side, the bottom two boards weren’t fully nailed down but only had nail heads. These boards served as a hinged trap, with the opening secured by a latch. As R.D. Adams explained, Houdini would remove his handcuffs while the crate was being sealed. Once in the water, Houdini would unlock the trap and swim to the surface.

In one instance of the box escape, Houdini waited until the crate hit the riverbed before opening the trap. The crate landed with the trap facing downward, and the muddy riverbed kept the door from opening. Only after struggling against the side of the crate could Houdini manage to release the trap. From that point on, Houdini always ensured that the trap was open before reaching the bottom of the river.