John Wayne, a towering figure in Hollywood, was celebrated for his unique voice, iconic gait, and patriotic demeanor. While contemporary audiences might recall his controversial statements and his decision not to serve in World War II, Wayne remains a multifaceted and intriguing personality with an extensive filmography.

By the time of his death from cancer in 1979, Wayne had appeared in nearly 250 films, including several masterpieces that showcased his exceptional talent. Classics like Stagecoach, The Searchers, and The Shootist highlight his remarkable career. However, Wayne wasn’t satisfied with just acting; he aspired to direct as well.

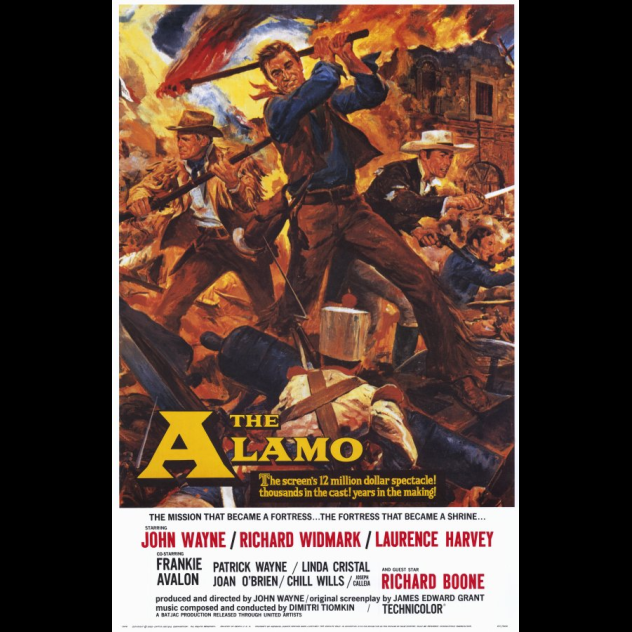

Wayne was particularly passionate about directing a film centered on the Alamo, the historic battle where a small group of Texans made a heroic last stand against a vastly larger Mexican force. Yet, when he finally secured the opportunity to bring his vision to life, the production descended into chaos, becoming one of Hollywood’s most infamous filmmaking disasters.

10. A Rocky Start

Since 1944, John Wayne had dreamed of creating a film about the Alamo. The story resonated deeply with his patriotic ideals. A staunch patriot, Wayne was inspired by the bravery of the Alamo’s defenders and aimed to motivate what he saw as a complacent 20th-century audience to defend their beliefs. His third wife, Pilar, noted that the film was Wayne’s way of opposing those who lacked faith in traditional American values.

Wayne’s dedication to the Alamo was so profound that author Gary Wills described it as his “true religion,” a cause he was willing to sacrifice for. However, despite his enthusiasm, launching the project was no easy feat. In the 1940s, tied to Republic Pictures, Wayne faced constant delays from studio head Herbert Yates. Frustrated, Wayne eventually left the studio to pursue the film independently. Ironically, Yates later approved an Alamo movie, possibly as retaliation for Wayne’s departure.

Wayne soon realized that Hollywood studios were hesitant to back him as a director. After numerous rejections, he secured a deal with United Artists. They agreed to distribute the film, provide $2.5 million, and grant Wayne creative control, but with conditions: he had to commit to a three-picture deal and star in the film. Initially, Wayne had planned only a cameo as Sam Houston, but United Artists insisted he take on the lead role of Davy Crockett.

9. Constructing San Antonio

With The Alamo finally moving forward, Wayne had to find the ideal filming location. Initially, he thought about shooting in Mexico to avoid union rules and high costs for extras. However, when influential Texans—oil tycoons, media moguls, and political leaders—caught wind of his plan, they sent a stern warning. Filming in Mexico would mean no financial support from Texas institutions and a ban on the movie’s release in Texas theaters.

Realizing his Mexico plan was doomed, Wayne quickly shifted his focus to Texas. This led him to James T. “Happy” Shahan, a rancher-turned-politician and mayor of Bracketville, a small town near San Antonio. Shahan owned a vast 22,000-acre property and envisioned it as a Hollywood film set. He persuaded Wayne to film there, and the Duke, impressed by the land, agreed. With the location secured, Wayne successfully convinced Texas businessmen to invest in the project.

While networking with figures like Governor Price Daniel and the publisher of The Houston Chronicle, Wayne transformed Shahan’s ranch into a 19th-century “Alamo Village.” Extras were brought from across the border to craft over a million adobe bricks for the set. Art director Al Ybarra meticulously recreated the Alamo to scale. The crew installed electric wires, a sewer system, and even built an airstrip for transportation to and from the set.

For this historical epic, Wayne required a significant number of animals. With Shahan’s assistance, he gathered around 1,400 horses and roughly 300 Texas longhorns. These animals were housed in newly constructed corrals spanning 500 acres. The team even laid railroad tracks to deliver animal feed directly to the set.

Unsurprisingly, this project was a financial behemoth. The set construction alone cost approximately $1.5 million, much of which Wayne funded personally. His dedication to the Alamo film was so intense that he mortgaged two homes, all his vehicles, and even his production company, Batjac. This high-stakes gamble led Wayne to admit, “My career, my wealth, and my reputation are on the line.” He believed his entire existence, including his “soul,” depended on the success of this film.

8. Casting Challenges

With Wayne cast as Davy Crockett, he needed actors for the other two leads: Jim Bowie, the knife-wielding adventurer, and William B. Travis, the military leader. Initially, Wayne considered Clark Gable and Frank Sinatra for Travis but ultimately chose British actor Laurence Harvey, famous for his role in The Manchurian Candidate. Many Texans were displeased with a foreigner portraying their hero, but Wayne dismissed their concerns.

For Bowie, Wayne initially wanted Burt Lancaster but ended up selecting Richard Widmark, known for roles in Kiss of Death, Judgment at Nuremberg, and Murder on the Orient Express. This decision led to tension, as the two men clashed almost immediately. Their conflicts may have stemmed from their opposing political views—Widmark was a liberal, while Wayne was a staunch conservative—or perhaps Widmark’s lack of respect for Wayne’s directing inexperience. Regardless, their animosity was evident from the start.

For instance, when Widmark joined the project, Wayne placed an ad in The Hollywood Reporter that said, “Welcome aboard, Dick. Duke.” However, upon arriving at Alamo Village, Widmark corrected Wayne, saying, “Tell your press agent the name is Richard.” Wayne retorted, “If I ever take another ad, I’ll keep that in mind, Richard.” Their relationship only deteriorated from there.

Another casting issue arose when Wayne sought an actor to play Jethro, Jim Bowie’s slave. Sammy Davis Jr. was eager for the role, hoping to redefine his image, but the Texas financiers opposed his involvement due to his Rat Pack persona and his relationship with white actress May Britt. Despite Davis’s efforts, Wayne cast Jester Hairston as the subservient slave, a decision that has sparked debate among film enthusiasts.

Wayne also brought in pop star Frankie Avalon to attract younger audiences and bullfighter Carlos Arruza to appeal to Hispanic viewers. He personally selected every actor and stunt performer for the film. Alongside the 342-member cast and crew, thousands of extras were transported daily from Mexico. Before filming began, over 300 people gathered on set for a blessing ceremony led by a local Catholic priest.

They probably should’ve prayed more fervently.

7. A Series of Catastrophes

Even before filming began, the set of The Alamo faced a series of calamities. As the crew crafted adobe bricks for Alamo Village, a torrential downpour dumped 74 centimeters (29 inches) of rain on Happy Shahan’s ranch. The resulting flood nearly destroyed all their progress, setting the tone for the challenges ahead.

Following the flood, Shahan’s daughter and two Alamo crew members were in a near-fatal car accident. Soon after, the film’s publicity office caught fire. Despite efforts by actors and crew to extinguish the flames with hoses, critical documents, including payroll records and promotional materials, were lost. The situation worsened when 80% of the cast and crew fell ill with the flu, compounded by the constant threat of rattlesnakes and scorpions on set.

Even the stars weren’t spared from misfortune. During a pivotal scene, Laurence Harvey, portraying William Travis, stood atop the Alamo walls addressing a Mexican messenger. When Travis defiantly fired a cannon, it recoiled and crushed Harvey’s foot. Despite the injury, Harvey remained in character and completed the shot.

Once filming paused, Harvey screamed in agony but refused to seek medical attention. Instead, he treated his injury on set by alternating between hot and cold water baths. While his toughness impressed Wayne, these incidents were overshadowed by a tragic event involving a rising starlet.

6. The Alamo Murder

LaJean Ethridge was part of the Hollywood Starlight Players, a theater group that toured Texas. When her troupe discovered John Wayne was filming in Bracketville, Ethridge and her five male colleagues joined as extras. Her talent caught the eye of casting director Frank Leyva, who gave her a speaking role, allowing her to stay at Fort Clark with the main cast and crew. The rest of the Starlight Players remained in Spofford, 32 kilometers (20 miles) away.

This arrangement didn’t sit well with Ethridge’s boyfriend, Charles Harvey Smith.

Ethridge excelled in her scene, prompting Wayne to ask her to participate in publicity shoots and expand her role with a higher salary. This further enraged Smith, who demanded she return to Spofford. When Ethridge refused and ended their relationship, Smith, in a fit of jealousy, fatally stabbed her with a 30-centimeter (12-inch) knife. Her final words were reportedly, “I love you.”

Wayne was deeply affected by her death but also concerned about the film’s progress. With The Alamo costing $60,000 daily, halting production wasn’t an option. He continued filming around the police investigation but faced complications when subpoenaed to testify at Smith’s hearing. Determined to avoid delays, Wayne even had Texas highway patrol set up roadblocks to intercept the lawyer and dissuade him from pursuing the subpoena.

Eventually, Wayne was permitted to provide a deposition, and he later informed the press that he hoped Smith would face the death penalty. However, the murderer was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

5. The Duke’s Growing Frustration

By this stage, John Wayne was understandably frustrated. His stress levels were so high that he was smoking more than 100 cigarettes daily. The scorching Texas heat—nearly 40 degrees Celsius (100 °F)—only worsened his mood. The combination of the heat and his heavy costume caused Wayne to lose approximately 4 kilograms (10 pounds) of water weight each day. To make matters worse, his constant sweating weakened the adhesive on his toupee, causing it to slip frequently.

To add to the chaos, Richard Widmark and Wayne’s feud showed no signs of cooling. Widmark frequently criticized Wayne on set, and one night, he stormed to Wayne’s quarters, demanding to be released from his contract. Wayne, in the middle of a meal, refused to discuss work. When Widmark pushed further, Wayne, towering over his co-star, ordered him to leave.

The tension escalated when Wayne called Widmark “a little s—t,” nearly leading to a physical altercation. After this heated exchange, both actors dialed back their hostility. However, Wayne remained on edge throughout the shoot, even hurling rocks at inattentive cameramen. When a plane of curious onlookers flew over the set, Wayne grabbed a prop rifle and began shooting blanks into the air.

Wayne’s temper eventually led to an embarrassing incident. While filming, he heard chatter behind his director’s chair and erupted into a profanity-laden rant, laced with religious and sexual expletives. To his horror, he discovered the noise came from a group of visiting nuns. Wayne quickly apologized, but the awkwardness only foreshadowed more troubles ahead.

4. The Arrival of John Ford

When compiling a list of the greatest directors in history, John Ford undoubtedly earns a spot. A four-time Oscar winner, Ford has inspired legends like Steven Spielberg and Akira Kurosawa. He also played a pivotal role in launching John Wayne’s career, casting him in his breakout role in Stagecoach and directing him in timeless classics such as The Searchers, The Quiet Man, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Wayne felt deeply indebted to Ford, treating him like a father figure. However, Ford was far from nurturing. Known for his sadistic tendencies, the one-eyed director often mistreated his actors, both verbally and physically. Despite his imposing presence, Wayne frequently bore the brunt of Ford’s abuse, enduring it in silence.

When Ford arrived on the set of The Alamo, Wayne was torn. Ford immediately began dictating how scenes should be shot, often yelling, “Do it again!” When Wayne questioned him, Ford would snap, “Because it was no damn good!” On one occasion, Ford overruled Wayne’s instructions to an actor, scoffing, “Oh, what the hell does he know about that stuff?”

Wayne, ever the loyal student, was at a loss. While he wanted full directorial credit and to avoid rumors of Ford’s influence, he couldn’t bring himself to dismiss his mentor. Instead, Wayne devised a clever solution: he spent $250,000 to create a separate unit for Ford, tasking him with filming battle scenes away from the main production.

Historians debate the extent of Ford’s contribution to the film. Some claim Wayne didn’t use any of Ford’s footage, which infuriated the veteran director. However, writer Scott Eyman estimates Ford’s work accounted for 10–15 percent of the movie. Regardless, Ford provided a glowing endorsement, declaring The Alamo “the most important picture ever made.”

3. Remember The Alamo

Ultimately, Hollywood revolves around profitability. A film’s critical reception matters less than its box office performance. The Alamo performed remarkably well, ranking among the top 10 highest-grossing films in the US in 1960. While it was banned in Mexico, it drew large crowds in countries like England and Japan.

Despite the film’s success, Wayne wasn’t profiting. The Alamo had far exceeded its budget, and Wayne, having invested heavily by mortgaging his homes and production company, was now in debt. “The picture lost so much money,” Wayne admitted, “I can’t even buy a pack of gum in Texas without a co-signer.” To manage his financial crisis, Wayne had to sell his stake in The Alamo to United Artists.

This financial turmoil hit Wayne at a low point. Alongside the film’s failure, his financial advisor made poor investments, and his close friend Ward Bond passed away from cancer. These events plunged Wayne into depression, but he bounced back, continuing to star in hit films and even winning Best Actor for 1969’s True Grit. Texas later honored him as an honorary Texan.

United Artists eventually turned a profit by rereleasing the film multiple times. The Alamo Village set appeared in other movies and served as a tourist attraction until its closure in 2010. Despite the setbacks, disasters, and criticism, Wayne remained proud of The Alamo. As co-star Linda Cristal noted, “John loved The Alamo as a man loves a woman once in a lifetime—passionately.”

2. Chill Wills’s Oscar Campaign

After the final cut, score, and edits, The Alamo premiered in 1960. Realizing the film was too long, Wayne cut 40 minutes before its release. Critics panned the movie, but Wayne and Birdwell pushed for Oscars, hoping awards would boost the film’s appeal and help recover its massive budget.

During the Oscar campaign, Wayne and Birdwell pressured Academy voters, implying that voting against the film was unpatriotic. Their aggressive lobbying paid off, earning The Alamo seven Oscar nominations, including Best Picture. (Notably, more deserving films like Psycho were overlooked.)

While Wayne was overlooked for Best Actor and Best Director, Chill Wills received a Best Supporting Actor nomination for his role as Beekeeper, one of Davy Crockett’s loyal companions. Wills, known for roles in Giant, Meet Me in St. Louis, and the Francis the Talking Mule series, hired PR manager W.S. “Bow-Wow” Wojciechowicz, hoping to secure his first Oscar.

Bow-Wow employed outrageous tactics, including an ad listing every Academy member alongside Wills’s photo, captioned, “Win, lose, or draw, you’re my cousins, and I love you all.” This prompted Groucho Marx to respond with his own ad: “Dear Mr. Chill Wills, I’m happy to be your cousin, but I voted for Sal Mineo.”

Bow-Wow escalated his campaign with another ad in The Hollywood Reporter, claiming, “We of The Alamo cast are praying harder than the real Texans prayed for their lives in the Alamo for Chill Wills to win an Oscar.” This angered Academy members and infuriated Wayne, who responded with an ad in Variety, stating, “I refrain from using stronger language because I’m sure [Wills’s] intentions are not as bad as his taste.”

Wills fired Bow-Wow, but the damage was done. Peter Ustinov won Best Supporting Actor for Spartacus, and The Alamo only secured one Oscar for Best Sound. Best Picture went to Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, leaving The Alamo cast to return home empty-handed.

1. Russell Birdwell, PR Man

Initially, John Wayne estimated The Alamo would cost $5 million, but expenses for extras, costumes, animals, and sets pushed the budget to $10–12 million, making it the most expensive film of its era. To generate buzz for the costly project, Wayne enlisted Texas PR specialist Russell Birdwell.

The outcome was somewhat . . . over-the-top.

Before joining Wayne, Birdwell had promoted films like Gone with the Wind and Howard Hughes’s controversial Western, The Outlaw. For the 1939 Civil War epic, Birdwell orchestrated a nationwide hunt for an actress to portray Scarlett O’Hara, generating immense publicity. Over three years, 1,500 actresses auditioned for the role. For The Outlaw, Birdwell famously showcased Jane Russell in provocative pin-up photos.

Known as “the P.T. Barnum of advertising,” Birdwell rejected subtlety and pulled out all the stops to promote Wayne’s film. He famously declared the Alamo battle as the most significant event since “the crucifixion of Christ.” As reported by Texas Monthly, Birdwell urged Congress to honor the Alamo defenders with the Medal of Honor and even proposed a global summit at the mission involving England, France, the US, and the USSR.

Birdwell’s crowning achievement was a nearly 200-page press kit, dubbed “The Bible,” filled with staggering statistics to impress audiences. It detailed the crew’s coffee consumption (510,000 cups), new roads built (23 kilometers [14 miles]), Spanish tiles used (2,800 square meters [30,000 square feet]), and ice cream eaten (900 gallons). His methods were as bold and extravagant as Wayne’s film, but not everyone approved. As Happy Shahan put it, “Birdwell was Wayne’s downfall.”