The initial goal was to compile a list of the top ten fugues in history, but it became clear that Johann Sebastian Bach would occupy every spot, along with hundreds more. To introduce variety, this list showcases ten exceptional fugues by other composers. While these may not be the absolute best non-Bach fugues, they are undoubtedly remarkable. Many deserving pieces were inevitably excluded, so feel free to share your personal favorites.

10. Fugue in C Major Johann Pachelbel

Indeed, Pachelbel composed more than just the famous Canon in D Major. He created over two hundred organ pieces, his primary instrument, and hundreds more for various other instruments and voices. As one of Bach’s greatest influences, Bach extensively studied Pachelbel’s works, leading to similarities in the structure and techniques of their fugues.

This fugue is the lister’s top pick among those available on YouTube, though no opus number could be found for it. Pachelbel likely composed numerous fugues in C Major and other keys over his career. This particular piece is lively and enjoyable, featuring recurring melodic notes.

9. Fugue #4 in e Minor Op. 87 – Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich deeply studied Bach’s compositions, as any serious musician should (even heavy metal artists often admire Bach). This fugue reflects clear influences of the high Baroque style. Its theme appears simple but allows for intricate developments, and the piece is masterfully structured, gradually increasing in polyphonic richness. However, the emotional tone, distinctly late Romantic, evokes a sense of melancholy and distance, perhaps reminiscent of a desolate Russian landscape under a dreary rain.

8. Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta 1st Movement – Bela Bartok

Like much post-Romantic, 20th-century music, this piece defies easy description. Written without a key signature and strictly atonal, it nonetheless adheres closely to Baroque fugue traditions, making it both captivating and accessible. The music might evoke the image of a terrifying creature slowly and patiently approaching until, two-thirds through, the listener confronts it and must decide how to react, ultimately retreating cautiously. This is just one interpretation, but the piece’s overwhelming intensity is undeniable.

7. End of Act 2 Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg – Richard Wagner

As is characteristic of Wagner’s operas, he utilized every possible polyphonic technique to build layers of complexity into the monumental music demanded by his epic narratives. The conclusion of Act 1 in Lohengrin is another excellent example of his grand, Romantic polyphony. However, he surpassed himself with Die Meistersinger. In Act 2, Scene 6, Beckmesser, a mastersinger, tries to serenade Eva at her window but is repeatedly interrupted by Hans Sachs, another mastersinger, who hammers the soles of a pair of shoes each time Beckmesser errs. By the time Beckmesser finishes his song (directed at Magdalena, disguised as Eva), Sachs has completed the shoe repairs.

Their commotion awakens David, who, consumed by jealousy, attacks Beckmesser, sparking a neighborhood uproar that nearly escalates into a riot. This onstage chaos is masterfully unified by the fugue Wagner assigns to the characters and the orchestra.

6. Kyrie Eleison Requiem in d Minor – Wolfgang A. Mozart

One of Mozart’s most remarkable achievements, this movement demonstrates his exceptional skill in crafting intricate polyphonic music. It is a double fugue, merging the Kyrie Eleison and Christe Eleison into a single composition. Traditionally, these texts are separate, as the Greek/Latin liturgy reads, “Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison.”

The tones of these texts are often interpreted as “ominous” for the Kyrie and “pleading” for the Christe. The Kyrie is seen as invoking God the Father, who will judge sinners in the final days, while the Christe calls upon Christ, who intercedes for sinners. Mozart’s rendition follows this pattern. The movement opens with a powerful declaration from the basses, “Lord, have mercy!” swiftly answered by the altos in a frantic, rising staccato, “Christ, have mercy!” conveying a sense of urgency.

Though not lengthy, this fugue showcases a profound command of polyphonic techniques essential for maintaining thematic development. Crafting double fugues is far more challenging than single ones, and since Bach excelled in this form—most notably in his Art of the Fugue—later composers have felt compelled to prove their mettle. Verdi, for instance, struggled, producing a technically correct but overly academic double fugue in the Sanctus of his Requiem. Mozart, on the other hand, skillfully navigates these complexities, allowing for a thorough exploration of the themes.

5. Fugue in G Major BuxWV 175 – Dieterich Buxtehude

Buxtehude was Bach’s foremost inspiration. In Buxtehude’s compositions, Bach discovered the intricate divine complexity that Baroque music aspired to and ultimately achieved through Bach himself. If Bach represents the zenith of the Baroque era, Buxtehude laid the groundwork for his ascent.

Consequently, Buxtehude’s music lacks the weight and vigor of Bach’s, but this particular fugue exudes a joyful lightness, expanded into a spectrum of polyphonic textures and hues. It was ideally suited to its purpose: providing a lively interlude during lengthy, monotonous church services. Though shorter than many on this list, Buxtehude’s fugue is concise and impactful—a graceful, spirited dance of a composition.

4. Amen, Messiah George F. Handel

This list would be significantly lacking without acknowledging Handel. As Bach’s greatest peer, he was revered by Beethoven and Haydn, who regarded him as the finest composer of all time (despite having access to only a fraction of Bach’s works during their era). Handel’s monumental oratorio, Messiah, concludes with an equally grand fugue centered on the single word, “Amen.”

Handel was the second most accomplished master of the Baroque fugue, a remarkable feat given the form’s prominence in Baroque music compared to later periods. He enjoyed far greater fame and wealth across Europe than Bach, serving under King George II of England. In contrast, Bach’s employment was limited to churches, which struggled to afford even basic necessities, let alone music. Bach’s income was supplemented with firewood and grain, and he couldn’t gather the funds to visit England and meet his greatest contemporary.

Handel’s “Amen” serves as the climactic conclusion to what many call “the greatest story ever told.” To achieve this, he introduces trumpets for a majestic, triumphant fanfare, described by some as a final assault on Heaven. The fugue’s complexity rivals Bach’s best, with some scholars arguing it surpasses even the “Hallelujah” Chorus in brilliance.

3. Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 Ludwig van Beethoven

At the time of its premiere, Beethoven had yet to be universally recognized as a master of counterpoint. Today, his genius is undeniable. His “Grosse Fuge,” initially the final movement of his String Quartet, Op. 130 in B-flat Major, baffled audiences due to its dissonant theme—a novel and unsettling concept at the time. Unfazed, Beethoven composed as he heard the music in his mind, unafraid to experiment. If it resonated with him, he pursued it relentlessly.

Beethoven removed the fugue from the quartet and replaced it with a more accessible movement, publishing the fugue as a standalone piece. The Schuppanzigh Quartet, led by the exceptional violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, premiered it. After the performance, Schuppanzigh admitted to a fellow quartet member that he didn’t comprehend the fugue but didn’t dare challenge “the Generalissimo.”

This double fugue features four voices developing two themes simultaneously. Like Mozart and Haydn, Beethoven had limited access to Bach’s fugal works, primarily studying from the Well-Tempered Clavier. It’s remarkable that Beethoven advanced the form, especially since Bach’s comprehensive “The Art of the Fugue” remained undiscovered until Felix Mendelssohn unearthed it in 1829.

2. Symphony 41, 4th Movement Wolfgang A. Mozart

Mozart composed this entire symphony in roughly a month during the summer of 1788, alongside Symphonies 39 and 40—his final three symphonies—and numerous other works. The final movement epitomizes Mozart’s style: joyful, exuberant, and brimming with laughter and elation.

This lister acknowledges a slight stretch in including this piece, as it is technically a “fugato” rather than a strict fugue. A fugato mimics the fugue style but incorporates enough modifications to loosen its structure, often resulting in multiple interwoven fugues. Mozart employs this technique with a four-note theme, developing five distinct voices, each altering the theme uniquely. These variations are explored across the orchestra before converging in a grand finale. While scientifically intricate, its full brilliance is best appreciated through score analysis.

1. Hammerklavier Sonata 4th Movement – Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven had an aversion to writing counterpoint, as it didn’t come naturally to him. However, his relentless determination drove him to conquer the fugue’s immense technical challenges. After a career filled with composing some of history’s most monumental music, including numerous fugues and fugal sections, he solidified his reputation as a master of counterpoint with the fugal finale of this sonata.

This movement is notoriously challenging for classical pianists due to its sheer scale, featuring three voices in triple meter and spanning 12 minutes. Memorizing it is a formidable task. For much of the 19th century, this sonata was the longest solo piano work. The fugue, built on a dissonant theme—a bold and unconventional choice for the time—is structured around three voices rather than four. Beethoven, as always, remained indifferent to public opinion.

Like much of Beethoven’s piano repertoire, this piece incorporates extensive trilling. Sviatoslav Richter compared its composition to Noah building the Ark: only one man could accomplish such a feat, and he was chosen by divine will. The movement begins simply, methodically laying a foundation, then contemplates its progression before culminating in the construction of the Ark’s rounded walls.

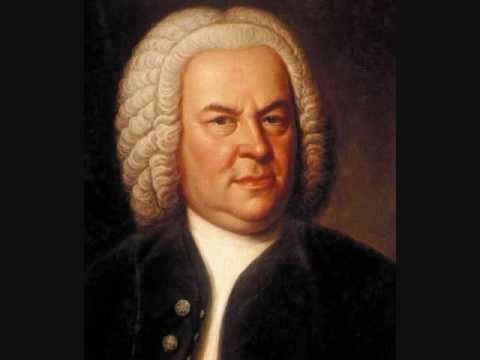

+ “Little” Fugue in g Minor BWV 578 – Johann Sebastian Bach

In any music appreciation or history course, you’ll encounter the fugue—its origins, its renowned composers, and a basic understanding of its structure. Every textbook on the subject references Bach’s “Little” Fugue in G Minor. This nickname distinguishes it from his longer fugue, BWV 542, also in G minor, which is equally celebrated. The “Little” Fugue stands as the most succinct and masterfully crafted fugue in history, though it may not necessarily be Bach’s greatest, a title too subjective to assign. Nonetheless, all fugal compositions since Bach, whether intentionally or not, draw from the techniques he perfected, and this fugue remains the clearest and most direct illustration of his genius.