Recently, visual art has fallen under heavy criticism. A legacy beginning with Duchamp’s infamous graffitied urinal has given rise to a wave of 'What is art?' works that now fill galleries worldwide. This so-called 'art' is adored by individuals who, had they lived in the 19th century, might have been more inclined to invest in monocles and beaver fur stoles than to immerse themselves in the study of the natural world, art, or literature. But this wasn’t always the case—once, art was both deeply inspiring and inspirational. In some untouched corners of today’s culture, this tradition still quietly lingers, waiting.

Art was never always about the vivid, primary-color bursts seen in Van Gogh’s works or the tranquil, pastel landscapes by Monet. It wasn’t always about the grand heroic figures of Greek and Roman marble sculptors or the exploration of beauty as seen in the works of Klimt, Botticelli, or Michelangelo. The darker aspects of life have always had a place in art too...

“The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance” – Aristotle. Keep this quote in mind as you read through this list, and you’ll likely find yourself lying awake at night.

10. Mad Kate by Heinrich Füssli (1806, Oil)

The unsettling, the eerie, or, more academically, an image that portrays 'situational ugliness' is key in triggering fear responses in humans. Renowned author and medievalist Umberto Eco discusses this idea in his book On Ugliness, noting, 'The governing principle behind every story about ghosts or other supernatural events, in which we are frightened or horrified by something that isn’t going the way it should…'

Take a look at her. Things are certainly not unfolding as they should in this scene.

If you start at the bottom of the portrait and look upward slowly, one might expect to see a kind, gentle woman, perhaps awaiting loved ones for a peaceful picnic. Observe the surroundings—a clear blue sky, some greenery, a sweeping hillside, and rays of sunlight shining through. Then, focus on her face. The wild, unpredictable gaze, pupils pointing in unexpected directions, unruly hair, and a cape rising violently into a (shockingly) jet-black sky. Add to that the title—Mad Kate. She certainly seems to embody it.

This painting encapsulates two primal fears we all share: the loss of sanity (the autonomy of mind) and the terror of confronting the unexpected. Who among us would want to be alone in the wild with Mad Kate?

9. Drawings by Abused Children (Tragically) Ongoing, Mixed Media

The purity of children is a wonder. When that innocence is violated, forcibly torn away by the harmful actions of an adult, it stands as one of the most monstrous crimes humanity can commit. Objectively evil.

Many children express their trauma through art—the familiar image of children drawing simplistic stick figures and houses with smiling suns in the corner takes on a heartbreaking meaning when the child has been abused. Homes may be drawn without doors or windows, signifying no escape. A parent may appear smiling, but their mouth is filled with sharp, menacing teeth. Sometimes, abusive adults are depicted with long, claw-like fingers or arms, while the child may be drawn with no arms at all.

When abuse is suspected in a child, it often becomes clear through their drawings. In one way, this is a good thing—these subtle signals can help authorities or unaware parents identify the abusers and bring them to justice. But in another way, it’s tragically wrong—a blank piece of paper and a box of crayons should be a space for a child’s imagination to roam free, crafting vibrant, alternate realities. When their minds are clouded with unspeakable terror, it’s no surprise their drawings reflect those horrors. These 'works of art' are among the hardest to witness but perhaps the most crucial to prevent further suffering.

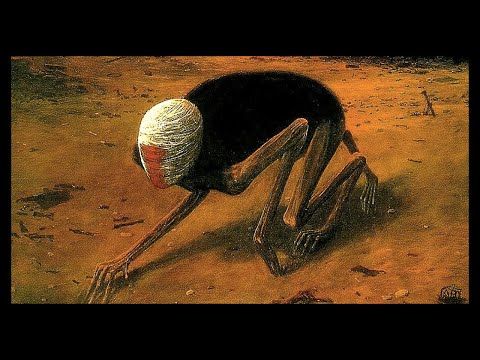

8. Untitled by Zdzislaw Beksinski (1975, Oil)

Critics have dubbed Polish artist Zdzislaw Beksinski as 'The Nightmare Artist.' Hard to disagree! The piece chosen here—Untitled (the title shared by much of his work)—is just one of many twisted, chilling creations that probe the depths of our shared psyche. It’s truly horrific.

Otherworldly, eldritch horrors roam through landscapes that seem designed to drive the mind to madness, making the viewer silently thank the heavens that these twisted visions are nothing more than paint on a canvas. But who would dare to hang such a piece on their wall without a lingering fear that one night, under the right—or wrong—alignment of stars, these creatures, tortured souls, and demonic entities might begin to emerge from the artwork and into our world?

Sweet dreams were never intended to be made from this.

7. Gas by Edward Hopper (1940, Oil)

Artist Charles Burchfield once described American painter Edward Hopper’s work as a 'genuine representation of the American scene… Hopper does not dictate how the viewer should feel.' Well, Charlie, while we can't fully decipher Hopper's intentions when he created Gas, consider the following perspective:

“This is Purgatory!”

It’s hard to ignore the sense of foreboding in this piece. Much like the ominous warning 'A murder is about to happen' or 'A natural disaster is imminent,' there’s an undeniable unease here. Hopper typically worked with darker tones, shadows, and somber urban settings or nighttime cityscapes. But in Gas, the scene unfolds in the bright daylight at a gas station. Still, something feels horribly off. Perhaps it's just an ordinary gas station, or perhaps Hopper has imbued the very paint with creeping dread. Every horror film has a similar setting, doesn’t it?

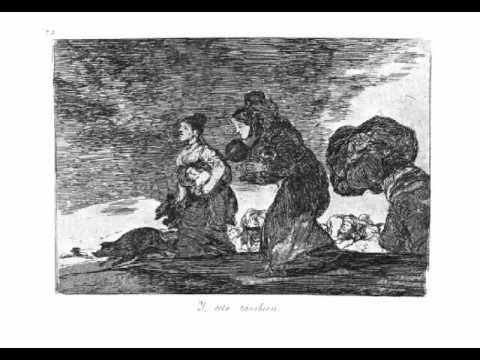

6. This Is Worse by Francisco Goya (1815, Drypoint)

Many artists have sought to portray the raw devastation of war over the years—Otto Dix's powerful depictions of WWI soldiers, J.M.W. Turner’s Battle of Trafalgar depicting naval warfare, and Picasso’s Guernica highlighting the horrors of aerial combat. But Francisco Goya’s The Disasters of War stands apart, offering the most visceral and haunting portrayals of the horrors of war and its devastating effects on the home front and the corrupted populace.

Many of the scenes in The Disasters of War reflect Goya's firsthand experiences or the stories he heard. For example, in For a Clasp Knife, a priest is shown strangled with a garrote, his body marked with a note detailing the crime for which he was punished. Most of the images in this series, except for a few more symbolic or fantastical works, serve as grim illustrations of war correspondence.

This is Worse stands as the most brutal and disturbing image in the series—a mutilated Spaniard is pinned to a twisted tree stump, branches impaling his body like a butchered carcass in a window. His head turns towards the viewer, mouth agape as if in a silent scream, adding to the grim realism of the piece. In the background, French troops continue their brutal campaign, heightening the horrors of this scene.

The scene takes place in 1808 near Chinchón, Spain, where French troops, in retaliation for the killing of two of their soldiers by local rebels, carried out a massacre of the men of Chinchón. If you want to grasp the true horrors of war without witnessing it firsthand, this series—especially this image—will bring you close. Be warned.

5. The Various Paintings Depicting the Beheading of John the Baptist—Caravaggio (1607-1610, Oils)

If you prefer your biblical stories to feature animated fruit and vegetables, these paintings are not for you. In fact, it might be best to stay away from the internet altogether!

Caravaggio, the audacious and violent Italian artist, who just so happened to be one of the most incredibly talented painters to ever wield a brush, had the rare ability to create works that were both horrifying and awe-inspiring. These paintings, all portraying the same Biblical event, are as stunning as they are grotesque.

In Caravaggio's works, violence and divinity are intertwined, bringing the Biblical tale to life in a way words cannot convey. It also comes as no surprise that the artist, known for his love of brawls, duels, murder, and throwing plates of artichokes at tavern owners, was also capable of such masterpieces. (Okay, he only did that once.)

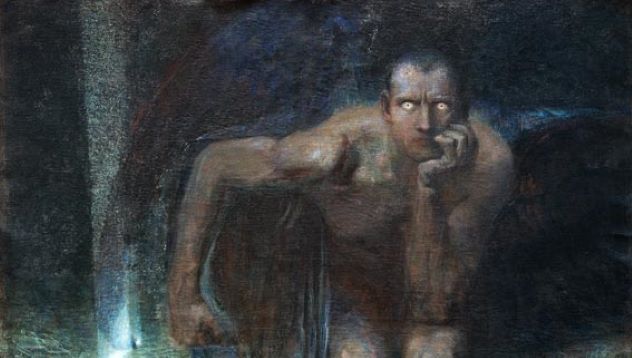

4. Lucifer—Franz Von Stuck (1891, Oil)

Over the past century, the devil has been softened in popular culture. From a cigarette brand mascot to a sympathetic character in TV series and a frequent mention in pop songs, Old Nick has become somewhat fashionable—perhaps even kitschy.

Franz Von Stuck’s chillingly minimalist portrayal of Lucifer forces the viewer to confront the essence of the original figure. The figure’s intense, unblinking eyes demand attention amidst the surrounding darkness. Imagine Lucifer—cast out of Heaven, unable to accept or comprehend his own nature, doomed to eternal opposition. The longer you gaze, the more the older, darker vision of the devil begins to resurface. This fallen angel is left questioning the meaning of his fate. Those eyes communicate madness and futility.

Or perhaps, those eyes are beckoning you to join him in an endless contemplation of the inherent injustice of existence.

Those eyes.

3. The Dead Lovers (aka The Rotting Pair)—Unnamed Master from Swabia/Upper Rhine (c. 1470, Oil)

For centuries, Memento Mori—Latin for 'remember that you have to die'—has been a recurring theme in European art. Subtle symbols like skulls or hourglasses hidden in paintings or sculptures serve as reminders that while we live, we are all inexorably heading toward death. This reminder of our own mortality is also present in this work.

A bit on the nose, don't you think?

Unlike the cleverly hidden skull in Hans Holbein’s famous The Ambassadors, this piece by an unknown German master hits you squarely in the face. Originally depicting a young, newlywed couple (now housed in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio), the painting portrays them as decaying corpses, their bodies being ravaged by snakes, frogs, and other scavengers. Yet, even in their rotting forms, their closeness remains, symbolizing that while we all eventually die, love is eternal. Granted, there might have been a less graphic way to convey that message, but hey, different strokes.

2. Gin Lane—William Hogarth (1751, Etching and Engraving)

The early 20th century history of the U.S. demonstrated that alcohol prohibition was doomed to failure. Yet earlier works, such as Gin Lane, powerfully criticized hard alcohol, illustrating its destructive nature. Rather than being a preachy or puritanical piece, the engraving titled Gin Lane portrays a grim, harrowing scene of moral decay and abandonment. If everyone intending to binge drink were required to look at this for five minutes before heading out, they might reconsider ordering shots.

This engraving serves as a companion to another piece called Beer Street, which presents a contrasting scene of healthy and hardworking Londoners enjoying life. The underlying message here is that English beer is wholesome and beneficial, unlike the damaging foreign gin.

Gin Lane reveals a devastating scene—death, degeneration, and indulgence are vividly portrayed by the gin-drinking inhabitants of London’s St. Giles district. In the central image, a syphilitic prostitute, drunk on gin, allows her crying baby to fall to its death. This harrowing depiction echoes real-life tragedies from the era, such as the 1734 case of Judith Dufour, who strangled her daughter with newly gifted clothes from a workhouse before selling the garments for a pittance.

To purchase gin.

1. Head of Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens (1617–1618, Oil)

Caravaggio's interpretation of the mythological Gorgon’s severed head is widely regarded as one of the most chilling and iconic depictions of this story.

No, that’s incorrect—it’s actually Reubens.

Take a look at the writhing snakes. Even if you're not afraid of these venomous creatures, the sight of blood transforming into new, wriggling serpents is enough to make anyone uneasy. The scene also raises questions: why are there two random spiders and a salamander tucked away in the bottom corner? This grotesque moment adds a new level of drama to the myth—Perseus was tasked with stuffing this horrifying, venomous bundle into a bag. Would you dare to get close enough to touch this?