Numerous instances of unresolved and cryptic writing systems, codes, ciphers, languages, and maps remain undeciphered. This compilation highlights ten lesser-known examples, distinct from well-known cases like the Vineland Map and Voynich Manuscript, which are not suspected to be fraudulent.

Maps, languages, codes, and ciphers are frequently decoded, often after extensive research and computational efforts. Modern advancements include the use of computers to interpret previously unintelligible scripts. A notable achievement is the decryption of the Copiale Cipher, a 105-page manuscript from the late 18th century. As reported by The New York Times, the first 16 pages reveal it to be a detailed account of rituals from a secret society obsessed with eye surgery and ophthalmology. The decoded text describes mystical gestures, plucking a hair from a candidate’s eyebrow, and binding initiates to vows of loyalty and secrecy.

Below are ten additional enigmatic ciphers, maps, and languages.

10. British Library Ciphers

The British Library houses at least three entirely encrypted books or manuscripts. The first, 'The Subtlety of Witches,' was written by Ben Ezra Aseph in 1657. The second bears the intriguing title: 'Order of the Altar, Ancient Mysteries to Which Females Were Alone Admissible: Being Part the First of the Secrets Preserved in the Association of Maiden Unity and Attachment,' dating back to 1835. The third, with the enigmatic title 'Mysteries of Vesta,' is believed to originate from around 1850. Aspiring codebreakers with access to the British Library—start decoding!

9. Unknown Peruvian Language

A 400-year-old letter penned by an unidentified Spanish author has unveiled a previously unknown Peruvian language. Discovered in 2008 within the ruins of a Spanish Colonial church in El Brujo, northern Peru, linguists have only recently recognized that the letter contains clues to an entirely new language. On the reverse side of the letter are notes that seem to translate the unknown language into Spanish and Arabic numerals.

While the newly discovered language may draw elements from Quechua, still spoken by indigenous Peruvians today, it is evidently a distinct and previously unknown tongue. It might correspond to one of two languages referenced in historical texts—either 'Quingnam' or 'Pescadora,' meaning 'language of the fishers.' Likely rooted in Inca culture, the translated numerals suggest the use of a base-ten system (unlike the Mayans' base-twenty system). It is also plausible that these two names refer to a single language, and the clues on the envelope could assist linguists and scholars in deciphering this enigmatic language.

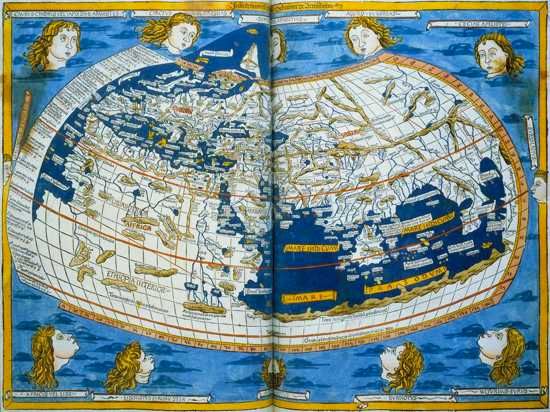

8. The Ptolemy Map Code

Though not a code or cipher, this mystery required 'decoding' to solve a historical puzzle: pinpointing the locations of ancient German towns encountered by the Romans. While the Romans frequently documented their interactions with Germanic tribes, the exact locations of these towns remained elusive. Historians struggled to align the 96 towns listed on an ancient German map with modern geography, leaving the question unresolved for centuries.

Claudius Ptolemy, the renowned 2nd-century Greek scholar, included a map of 'Germania Magna' in his work Geographia. In AD 150, Ptolemy essentially created an ancient version of Google Earth, crafting 26 maps in colored ink on animal hides to depict the known world. Despite never visiting Germany, Ptolemy relied on other accounts to create his map. However, matching the 96 towns he marked with modern German locations proved impossible—until recently.

After six years of meticulous work, a team of Berlin-based academic surveyors and cartographers has reportedly succeeded in remapping Ptolemy’s 96 German town coordinates to their modern equivalents. This breakthrough was made possible by the discovery of an earlier version of Ptolemy’s Geographia in the Topkapı Palace library in Istanbul, Turkey. The newly found map reveals ancient names for modern cities, such as Jena, referred to as 'Bicurgium,' and Essen, labeled 'Navalia.' The town of Fürstenwalde, known as 'Susudata' 2,000 years ago, derives its name from the Germanic term for 'sow’s wallow.' This is the only entry on the list that has been fully resolved.

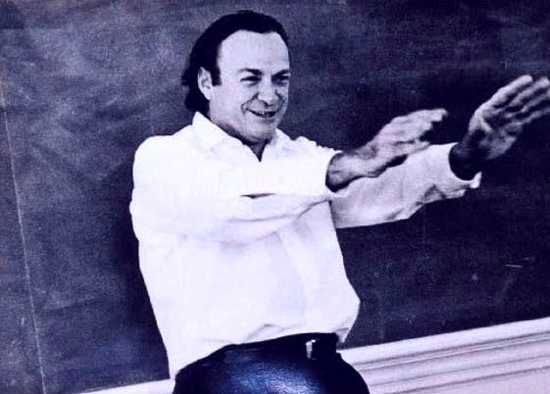

7. The Feynman Ciphers

In 1987, during the early days of the Internet, an individual claiming to be a graduate student of the renowned physicist Dr. Richard Feynman shared a message on a cryptology forum. According to the post, Feynman was presented with three coded samples by a fellow scientist at Los Alamos, who challenged him to decode them. The poster alleged that Feynman was unable to crack the ciphers and shared them online for others to attempt. Shortly after, John Morrison of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) successfully decoded one of the ciphers, revealing it to be the opening lines of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in Middle English. The remaining two ciphers remain unsolved. The original ciphers can be viewed here.

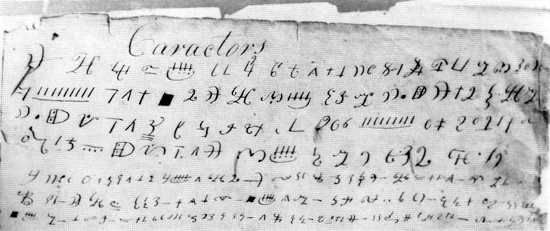

6. The Anthon Transcript

What exactly are the enigmatic 'Caractors' in the Anthon Transcript? Solving this mystery could validate or debunk a central tenet of the Mormon faith. The Anthon Transcript is a small piece of paper believed to be handwritten by Joseph Smith, Jr., the founder of Mormonism. It purportedly contains lines of characters Smith claimed to have seen on The Golden Plates—an ancient record he said he translated into the Book of Mormon. These characters, described as Reformed Egyptian, were allegedly revealed to Smith in 1823.

The document derives its name from Charles Anthon, a renowned classical writing expert at Columbia University in 1828. Anthon was asked to authenticate and translate the characters. Some Mormon adherents assert that Anthon verified the characters' authenticity in a letter to Martin Harris, an early follower of the Latter Day Saint movement and one of the Three Witnesses who claimed to have seen the golden plates. According to Harris, Anthon identified the writing as Egyptian, Chaldaic, Assyriac, and Arabic, calling them 'true characters.' However, upon learning the document was linked to Joseph Smith and Mormonism, Anthon allegedly destroyed his certification. Anthon later denied this, stating he always believed the writing was a forgery.

So, what are the 'Caractors'?

Anthon described the marks as 'merely an imitation of various alphabetical characters, with no meaningful connection.' While they might appear as random scribbles, this seems unlikely. The 'Caractors' in the Anthon Transcript were likely borrowed from multiple sources, possibly including shorthand versions of the Bible, with added random characters to mimic a genuine language. Alternatively, they could be exactly what Joseph Smith claimed. Without translation and deciphering, their true nature remains unknown.

5. The HMAS Sydney Ciphers

One of the most intriguing unsolved ciphers may or may not be a cipher at all, but rather a product of World War II political intrigue. On November 19, 1941, the HMAS Sydney, a Royal Australian Navy light cruiser, engaged in a battle with the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran. Despite being larger, more powerful, and better armed, the Sydney was lost with all 645 crew members, while the Kormoran suffered minimal casualties. The Sydney’s defeat is often attributed to the close proximity of the ships and the Kormoran’s surprise tactics and precise fire. However, some speculate that the German commander used illegal strategies or that a Japanese submarine played a role. The true events of the battle are suspected to be part of a larger cover-up.

This is where the Sydney Ciphers enter the story. Captain Detmers of the Kormoran was captured and sent to an Australian POW camp after his ship was sunk. In 1945, during an escape attempt, Detmers was recaptured with a diary written in what appeared to be Vigenere code, marked by small dots under certain letters. Australian cryptanalysts deciphered the diary, concluding it described the engagement between the Sydney and the Kormoran. However, this raises a question: why would Detmers use a code that was already known to be easily broken?

The mystery intensifies with later revelations that other Australian documents claim the diary was not in Vigenere code but an unspecified German code from WWII.

Another interpretation of the Detmer diary suggests it was encoded using the British Playfair code, a system already cracked by 1941. This raises further questions: why would Detmer use an English code he likely had no knowledge of, especially one known to be broken since World War I? What purpose would it serve?

Which is accurate? Did Detmers use the easily deciphered Vigenere code, an unknown German code, or the British Playfair code?

One plausible explanation is that the diary was not encoded by Detmers at all but by British or Australian authorities aiming to create the illusion of encryption. By using one of the three broken codes, anyone who 'discovered' the diary could easily decode it, producing a narrative that aligns with the British and Australian accounts of how a superior warship was lost to a weaker enemy.

The true enigma of the Sydney Ciphers may lie in uncovering who created them and for what purpose.

4. Bellaso’s Ciphers

In 1553, Italian cryptographer Giovan Battista Bellaso released a cryptography guide titled 'La Cifra del Sig. Giovan Battista Bellaso,' akin to an early 'Cryptography for Beginners.' He later published two more editions in 1555 and 1564, introducing challenge ciphers for readers to decode. Bellaso described these ciphers as containing 'beautiful and intriguing secrets.' He promised to reveal their contents if unsolved within a year, a promise he never fulfilled. The ciphers remained unsolved until 2009, when Tony Gaffney, a reclusive Englishman, deciphered one, uncovering a surprising connection to Renaissance astrological medicine—a remarkable feat, especially since Gaffney doesn’t read Italian.

Gaffney further impressed by cracking Bellaso’s cipher #7, which was even more challenging as it employed a completely different encryption method.

To the best of my knowledge, the remaining five Bellaso ciphers remain unsolved.

3. Twin Language

A captivating example of an enigmatic language, baffling to those attempting to decode it, is unique in that only two individuals—twin siblings—can speak and understand it.

Cryptophasia is a rare phenomenon where twins (identical or fraternal) develop a private language only comprehensible to them. Derived from 'crypto' (secret) and 'phasia' (speech disorder), it is often linked to idioglossia but also includes mirrored behaviors like synchronized walking and mannerisms. Despite its intrigue, cryptophasia remains poorly understood.

Once considered rare, cryptophasia is now believed to occur in up to 40% of twins. These private languages, unintelligible to outsiders, typically fade as the twins grow older and adopt more conventional forms of communication.

Twins appear to partially adopt or mimic adult language, especially when adult interaction is limited. During the language acquisition phase, twins or siblings often model adult speech imperfectly, using each other as references. While they don’t invent entirely new languages, they create unique words and structures based on fragmented exposure to adult speech. These linguistic adaptations, constrained by the phonological limitations of young children, often result in a language entirely incomprehensible to speakers of the original model language.

The most famous instance of twin language involves Poto and Cabengo—identical twins named Grace and Virginia Kennedy. They communicated in a unique language incomprehensible to others until around age eight. Their story inspired the 1979 documentary 'Poto and Cabengo' by Jean-Pierre Gorin. Despite their normal intelligence, the twins developed their own language due to limited exposure to spoken communication during their early years.

2. Ricky McCormick Notes

On June 30, 1999, the body of 41-year-old Ricky McCormick was found in a field in St. Charles County, Missouri. McCormick, an unemployed high school dropout with heart and lung issues, lived intermittently with his mother and was on disability at the time of his death. He had a criminal record and had served jail time for various offenses. His body was discovered miles from his home, with no signs of foul play or a determined cause of death.

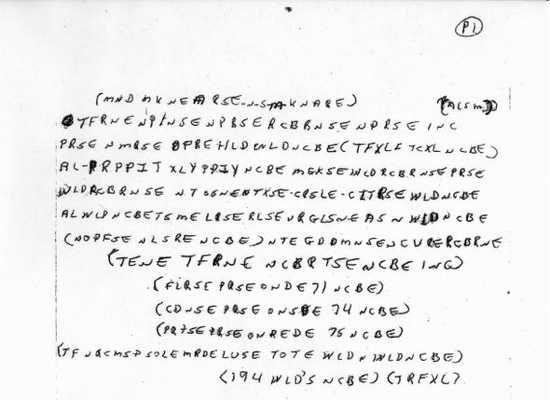

In his pockets were two handwritten, seemingly encrypted notes. Could these notes hold clues to his death? Both the FBI’s Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit (CRRU) and the American Cryptogram Association attempted, but failed, to decode the notes. Ricky McCormick’s death and the mysterious notes remain one of the CRRU’s top unsolved cases.

Twelve years later, the FBI reconsidered its stance, suspecting McCormick may have been murdered. They also believed the encrypted notes could hold the key to his death and potentially identify the killer(s). On March 29, 2011, the FBI appealed to global code-breakers for help in deciphering the messages. Shortly after posting the notes online, the FBI’s website was flooded with public responses offering theories, suggestions, and assistance. According to McCormick’s family, he had been creating encrypted notes since childhood, though no one in his family ever understood them. Now, the public is tasked with aiding the FBI in decoding these mysterious notes.

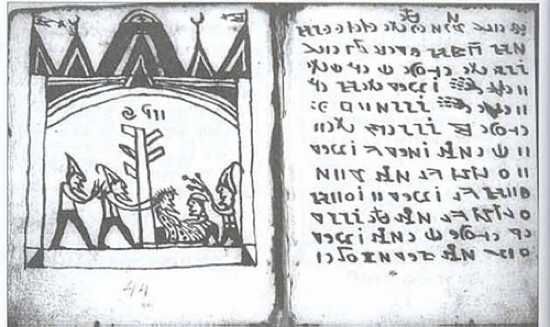

1. Le Livre des Sauvages

Emmanuel-Henri-Dieudonné Domenech, a French abbé, missionary, and author, responded to the call to expand the Catholic Church in Texas in 1846, traveling to America. He began in St. Louis, completed his theological studies, moved to Castroville, Texas, returned to France to meet the Pope, and then went back to Texas, arriving in Brownsville during the Mexican-American War. After further travels between France, Mexico, and Europe, he spent his later years as an ecclesiastical travel writer, even revisiting America in the 1880s.

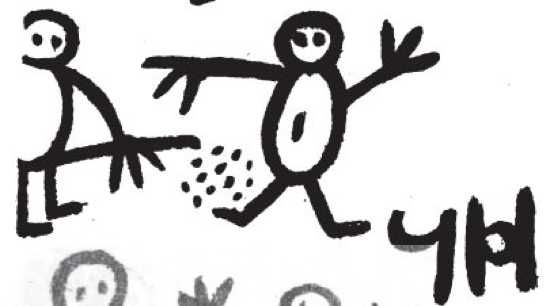

Perhaps due to numerous Atlantic crossings or extended time in Texas, Domenech created a peculiar and enigmatic document rediscovered in Paris’s Bibliotheque de l’Arsenal. Titled 'Le Livre des Sauvages,' Domenech claimed it was not his work but a Native American creation. However, German critics quickly debunked this, noting German words and characters throughout the text. The book also contained strange drawings—stick figures and symbols—that critics initially dismissed as childish scribbles. However, the drawings, often bizarre and sexually suggestive, appear to be the work of a troubled adult. Examples can be seen here.

'Le Livre des Sauvages' contains hundreds of pages filled with these peculiar illustrations. Among the drawings are fragments of cipher-like text, which may or may not form part of a larger code. However, given the explicit and sexual nature of the images, one might question whether anyone would be motivated to decode the accompanying text.