Building upon our previous list, Top 10 Ancient Innovations You Might Think Are New, we have curated another collection. It features items that were left out in the first list but are equally intriguing. Many of these things are often thought to be products of modern or medieval times, yet they all predate the birth of Christ. Feel free to share any other discoveries you might know in the comments section.

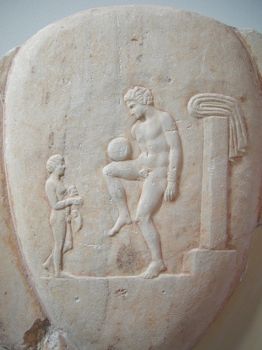

10. Football

The Ancient Greeks and Romans were known for their various ball games, many of which involved kicking the ball with the feet. The Roman game harpastum is believed to have evolved from a team game called episkyros. The Roman politician Cicero (106-43 BC) tells the story of a man who was killed during a shave when a ball was kicked into a barber's shop. These ancient games seem to have shared similarities with rugby football. Furthermore, there is documented evidence of an activity resembling football in the Chinese military manual Zhan Guo Ce, compiled between the 3rd century and 1st century BC. This practice, known as cuju (meaning “kick ball”), originally involved kicking a leather ball through a small hole in a silk cloth stretched over bamboo canes.

9. Toothbrushes

Oral hygiene practices have been around since long before recorded history. Various excavations across the globe have unearthed evidence of tools like chewsticks, twigs, bird feathers, animal bones, and porcupine quills used for cleaning teeth. Different cultures developed their own versions of toothbrushes. For example, Indian medicine (Ayurveda) has utilized the neem tree (also known as daatun) and its byproducts for thousands of years to create toothbrushes and similar tools. A person would chew one end of the neem twig until it began to resemble bristles, which could then be used to clean the teeth. In the Muslim world, the miswak, or siwak, made from a twig or root with natural antiseptic properties, has been commonly used since the Islamic Golden Age.

8. Sutures

Sutures have a strange and ancient history, dating back to ancient Egypt, where materials ranging from tree bark to hair were used to stitch human flesh. Physicians have employed sutures for wound closure for at least 4,000 years. Archaeological evidence from ancient Egypt reveals that Egyptians used linen and animal sinew for stitching wounds. In ancient India, physicians would use the pincers of beetles or ants to staple wounds shut, and then sever the insect’s body, leaving the jaws (acting as staples) in place. Other natural materials used for wound closure included flax, hair, grass, cotton, silk, pig bristles, and animal gut. Despite all the advancements, the fundamental principles of wound closure have remained largely unchanged over the millennia.

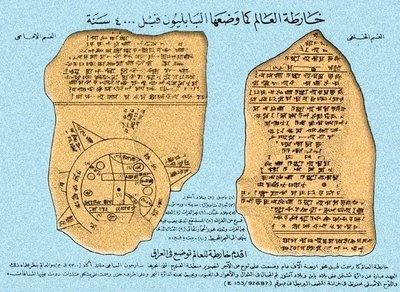

7. Maps

A Babylonian clay tablet, considered to be ‘the earliest known map,’ was discovered in 1930 at the ruined city of Ga-Sur in Nuzi, located 200 miles north of Babylon (modern-day Iraq). Small enough to fit into the palm of your hand (7.6 x 6.8 cm), this map-tablet is thought to date back to the dynasty of Sargon of Akkad (2,300-2,500 B.C.). The surface of the tablet is inscribed with a map of a district bordered by two mountain ranges and divided by a watercourse. This map is drawn with cuneiform characters and stylized symbols, either impressed or scratched into the clay. The tablet also includes inscriptions that identify various features and locations. [Source]

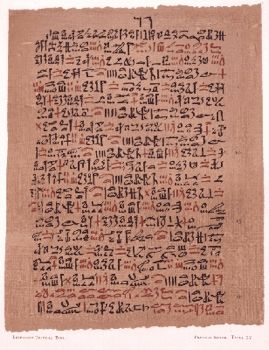

6. Soap

The earliest known evidence of soap-like substances dates back to around 2800 BC in Ancient Babylon. A formula for a soap composed of water, alkali, and cassia oil was inscribed on a Babylonian clay tablet around 2200 BC. The Ebers papyrus from Egypt (1550 BC) suggests that ancient Egyptians bathed frequently and combined animal and vegetable oils with alkaline salts to create a soap-like mixture. Ancient Egyptian texts also note that this soap-like substance was used during the preparation of wool for weaving. Galen, the ancient physician, describes the process of soap-making using lye and recommends washing to remove impurities from both the body and clothing. According to Galen, the best soap came from Germany, with soap from Gaul being considered second best. This marks the earliest record of soap as a cleaning agent.

5. Shipyards

The world’s first dockyards were established in the Harappan port city of Lothal around 2400 BC in Gujarat, India. Lothal's dockyards were connected to an ancient course of the Sabarmati river, which was part of the trade route between Harappan cities in Sindh and the Saurashtra peninsula, when the surrounding Kutch desert was once part of the Arabian Sea. The engineers of Lothal prioritized the construction of a dockyard and warehouse to facilitate naval trade. Located on the eastern side of the city, the dock is considered an impressive engineering achievement. It was positioned away from the river's main current to prevent silting but still allowed access for ships during high tide. The name of the ancient Greek city of Naupactus, meaning 'shipyard,' reflects its legendary status as the place where the Heraclidae are said to have built a fleet to invade the Peloponnesus.

4. Speculum

A speculum (from the Latin word for “mirror”) is a medical instrument designed to examine body cavities, with its shape tailored to the specific cavity being examined. Vaginal specula were in use by the Romans, and artifacts of such instruments have been discovered in Pompeii. The original examples were uncovered in the House of the Surgeon in Pompeii, a site known for the medical materials found there. These early specula consisted of a priapiscus with two (or sometimes three or four) dovetailing valves that could be opened and closed using a handle with a screw mechanism, a design that continued into 18th-century Europe. Soranus is the first known author to reference a speculum specifically made for vaginal use. Graeco-Roman medical writers on gynecology and obstetrics frequently recommended the use of specula for diagnosing and treating vaginal and uterine conditions, though it remains one of the rarest surviving medical instruments. [Source]

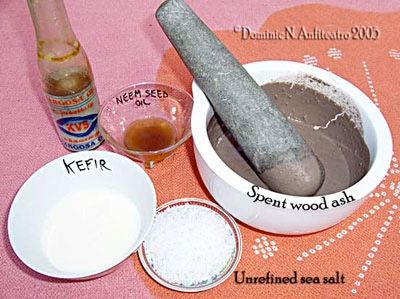

3. Toothpaste

The earliest known mention of toothpaste appears in a 4th-century A.D. Egyptian manuscript, which describes a mixture of iris flowers as an early form of toothpaste. Many early toothpaste recipes were based on the use of urine. However, it wasn’t until the 19th century that toothpastes or powders became widely used. The Greeks and Romans improved toothpaste formulas by adding abrasives like crushed bones and oyster shells. In the 9th century, Persian musician and fashion designer Ziryab is credited with inventing a type of toothpaste that he introduced throughout Islamic Spain. The exact ingredients of this toothpaste are unknown, but it was said to be both “functional and pleasant to taste.”

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.

2. Umbrellas

In the sculptures from Nineveh, the parasol is a common sight. Austen Henry Layard describes a bas-relief depicting a king in his chariot with an attendant holding a parasol over his head. This parasol, which has a curtain hanging behind it, is almost identical to modern parasols. It was reserved solely for the monarch (who was bald) and was never used for anyone else. In Egypt, parasols were depicted in various forms. Some were shown as flaellums, fans made from palm leaves or colored feathers attached to long handles, similar to those carried behind the Pope in processions today. In China, the 2nd-century commentator Fu Qian noted that the collapsible umbrella in Wang Mang’s carriage had bendable joints, allowing it to be extended or retracted.

1. Processed Rubber

Although vulcanization, a 19th-century innovation, is commonly associated with rubber, the history of rubber treatment through other methods dates back to prehistoric times. The term 'Olmec' translates to 'rubber people' in the Aztec language. Ancient Mesoamericans, from the Olmecs to the Aztecs, harvested latex from Castilla elastica, a rubber tree native to the region. This latex was mixed with sap from the local vine Ipomoea alba to create a form of processed rubber as early as 1600 BC. Archaeological findings show that rubber was already being used in Mesoamerica during the Early Formative Period, with numerous rubber balls discovered in the Olmec El Manati sacrificial bog. By the time of the Spanish Conquest, 3000 years later, rubber was being traded across Mesoamerica. Iconographic evidence suggests that although rubber had various uses, rubber balls, used in rituals and as offerings, were the most prominent products.