Experiments! An essential aspect of modern science. In this experiment, these women are monitored to observe their brain activity as they watch TV advertisements.

© David Levenson/Corbis

Experiments! An essential aspect of modern science. In this experiment, these women are monitored to observe their brain activity as they watch TV advertisements.

© David Levenson/CorbisMain Insights

- Ancient medicine relied on the idea that health was determined by the balance of four bodily humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile.

- Before modern science, it was commonly accepted that the Earth was at the center of the universe, surrounded by layers of cosmic spheres containing celestial objects.

- The concept that life could emerge spontaneously from inanimate matter was a widely held belief until it was disproven through scientific experiments.

Looking back, science has certainly pulled us out of some awkward and dangerous situations. It wasn't always the beacon of clarity it is today—it too explored some wildly unproven ideas in its early years.

If you ask science about its more awkward phases, it will likely drone on about how it once favored logic and deduction (a top-down method deriving specific truths from general principles), but later evolved into embracing induction (a bottom-up method that draws broad conclusions from repeated observations).

Naturally, science downplays just how long and cringe-worthy that awkward adolescence really was. Its long-lasting affair with Aristotle's flawed yet enticing natural philosophy lingered well beyond the Dark Ages. Science only truly exorcised its demons after Galileo’s groundbreaking discoveries in the 16th century and Francis Bacon’s call for self-reflection. Following that, science finally left its childhood behind, packed away its astrology posters, and entered the realm of structured inquiry—grounded in observation, hypothesis, data collection, experimentation, and testing—known today as the scientific method.

But, oh, the stories it could tell.

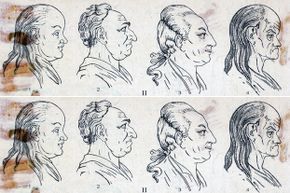

10: Temperaments Based on Bodily Fluids

The four temperaments (derived from the four bodily humors), from left to right: phlegmatic, choleric, sanguine, and melancholic. This illustration comes from Frank McMahon's "Psychology, The Hybrid Science."

© Bettmann/Corbis

The four temperaments (derived from the four bodily humors), from left to right: phlegmatic, choleric, sanguine, and melancholic. This illustration comes from Frank McMahon's "Psychology, The Hybrid Science."

© Bettmann/CorbisWithout a clear methodology, relying solely on reasoning can lead to numerous misguided conclusions, which makes it unsurprising that even the father of Western medicine produced his share of unsubstantiated ideas.

For instance, Hippocrates looked for natural explanations for what were once considered supernatural afflictions, like the 'sacred disease' of epilepsy, which was previously thought to be caused by divine or demonic possession. He also introduced the misguided theory of bodily fluids, or humors, which he believed determined health, personality, and appearance. This practice, based on balancing blood, phlegm, bile (choler), and black bile (melancholy), persisted until the 17th century. Its influence remains in terms like sanguine (Latin sanguineus 'of blood,' meaning optimistic) and melancholy (depressed). [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; NLM]

Doctors attempted to balance the humors through diet, exercise, and by examining bodily wastes like urine. While these methods had some merit, they oversimplified every condition, leading to the mismanagement of many diseases for centuries. Despite evidence of their shortcomings, physicians continued to rely on these humors, gradually associating them with qualities (wet/dry, hot/cold), elements (earth, air, fire, and water), and stages of life. These concepts are still present today in Ayurvedic medicine and traditional Chinese medicine [sources: NLM; Science Museum (UK)].

9: Cosmic Shells Surround Earth

It took an extraordinarily long time for us to settle on the current model of the solar system.

Fuse/Thinkstock

It took an extraordinarily long time for us to settle on the current model of the solar system.

Fuse/ThinkstockAncient Greek astronomers, grappling with the complexities of celestial movements, developed some unique theories, many of which were surprisingly close to the truth. Anaximenes, in the sixth century B.C.E., observed that planets drifted independently across the night sky. Similar to the Sumerians before him, he proposed that the stars were encased in an unchanging, eternal sphere that rotated around Earth—an idea that persisted long after geocentrism until Edmund Halley's 1718 observation of the independent motion of stars [sources: Belen et al.; Brandt; Graham; Kanas].

As further celestial observations posed challenges to the model, ancient astronomers kept refining their theory by adding more layers. They placed stars, planets, and even the sun and moon into separate celestial spheres, suggesting that these bodies were holes in a giant cosmic strainer, revealing the sacred fire beyond. When these holes were blocked, they were thought to cause the phases of the moon and eclipses [sources: Graham; Allen; Kanas].

This layering of spheres eventually led to the invention of increasingly intricate and complex models by Eudoxus in the fourth century B.C.E., who proposed as many as 27 nested spheres, each rotating independently and affecting each other. Eudoxus might have added more, but, as legend has it, William of Occam traveled back in time and stopped him with his razor.

8: A Central Fire, a Counter-Earth and a Few Epicycles

Many of Claudius Ptolemy's theories about the cosmos remained dominant for centuries, until the groundbreaking work of Copernicus challenged them all.

© Leemage/Corbis

Many of Claudius Ptolemy's theories about the cosmos remained dominant for centuries, until the groundbreaking work of Copernicus challenged them all.

© Leemage/CorbisThe ancient Greeks were well ahead of their time, believing the Earth to be round long before Columbus or Magellan sailed the seas. Some of them even questioned the idea of Earth being the center of the universe, although not always for the correct reasons.

Consider the Pythagoreans, a semi-mystical group led by the renowned mathematician Pythagoras in the sixth century B.C.E. They believed the Earth was not at the center of the universe, but instead orbited a Central Fire, along with the sun, moon, planets, stars, and even a fictional counter-Earth (known as antichthon). This idea of Earth in motion was a bold departure from traditional thinking at the time. The Pythagoreans, who followed a strict code against eating beans, touching fallen objects, or interacting with white roosters, believed in the ‘music of the spheres’ [sources: Allen; Burnet; Lewis and Chasles; Toulmin and Goodfield].

Attempts to uphold geocentrism, in light of observations that contradicted it, became increasingly bizarre and complicated. Mercury and Venus, whose movements seemed tied to the sun, were moved closer to Earth or even placed in orbit around it, while the sun continued to orbit Earth. In the second century, Claudius Ptolemy explained the phenomenon of retrograde motion—where planets appear to reverse their course—by introducing the concept of epicycles, or orbits within orbits. This complex Aristotelian-Ptolemaic view of the cosmos remained dominant until Nicolaus Copernicus restored the sun to the center, where it rightfully belonged, and Galileo confirmed his theory [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Gagarin and Cohen; Toulmin and Goodfield; Yost and Daunt].

7: All Matter Is Made From Water ... or Is It Air?

The four elements: earth, water, air, and fire

Thomas Vogel/E+/Getty Images

The four elements: earth, water, air, and fire

Thomas Vogel/E+/Getty ImagesIn the early days of Greek philosophy, thinkers believed that all matter was composed of a single substance, although they couldn't agree on exactly what that substance was. For Thales, the famed astronomer and mathematician, it was water; for Anaximenes, it was air (both lived in the sixth century B.C.E.). These choices weren’t random—they were based on observations of how matter changes states. For instance, Anaximenes observed how air could become visible and dense as it cooled into mist and rain, and theorized that it could condense even further into earth and rock [source: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Cohen].

Later on, Plato, ever the intellectual overachiever, introduced four elements to explain the composition of the universe: earth, air, fire, and water. Aristotle, not one to leave well enough alone, added a fifth element—ether—reserved for the heavenly bodies. With these five elements, they could account for the properties of various substances. For example, wood was solid (part earth), it floated (part air), and it burned (part fire) [sources: Armstrong; Plato].

The core idea—that, as Democritus proposed around 440 B.C.E., all matter is made up of minuscule, imperceptible particles—was remarkably close to the truth. However, solid evidence for atomic theory didn’t emerge until much later. In 1662, Robert Boyle conducted pivotal experiments with air pressure and vacuums. It took another century and a half before the English chemist John Dalton would formalize a widely accepted atomic theory in 1803 [source: Berryman].

6: Spontaneous Generation

Ever wondered how oysters form? Well, early natural philosophers had their own theories. They believed, under the concept of spontaneous generation, that oysters could simply appear from the seafloor, as though by magic.

Spike Mafford/Photodisc/Thinkstock

Ever wondered how oysters form? Well, early natural philosophers had their own theories. They believed, under the concept of spontaneous generation, that oysters could simply appear from the seafloor, as though by magic.

Spike Mafford/Photodisc/ThinkstockWhere does life come from? This question puzzled early thinkers, who wondered how maggots could emerge from a decaying body or how oysters might simply appear on the seafloor. Greek natural philosophers, who believed that all matter possessed intrinsic qualities, suggested that life could arise from basic substances under the right conditions. Similarly, the ancient Chinese thought that bamboo generated aphids [sources: Brack; Simon].

The theory of spontaneous generation sparked a series of amusing experiments, ridiculous conclusions, and heated debates—particularly among the likes of Voltaire and his 18th-century peers. But the real scientific groundwork began in the early 17th century when Flemish physician Jan Baptista van Helmont claimed that mice could spontaneously appear from a soiled shirt placed in a container with wheat grains, and that scorpions could emerge from a brick mold lined with basil leaves [sources: Brack; Simon]. No reports yet on whether a hamster might materialize from a Jamba Juice with chia seeds and whey protein.

In the quest for answers, the scientific community encountered two competing theories: the Preformationists, who believed that embryos were already fully formed within eggs or sperm (which some argued were like endless matryoshka dolls, stretching all the way back to Adam and Eve), and the epigenesists, who maintained that life emerged from simpler matter but couldn't agree on the force that drove the process [sources: Alioto; Maienschein].

These debates became bitter and often absurd, but the struggle to disprove spontaneous generation ultimately led to significant advancements in scientific methodology and experimental precision, which eventually uncovered the truth [source: Encyclopaedia Britannica].

5: Miasma Theory

In Victorian London, the dense, overpopulated city was believed to be teeming with a variety of foul-smelling miasmas.

© The Print Collector/Corbis

In Victorian London, the dense, overpopulated city was believed to be teeming with a variety of foul-smelling miasmas.

© The Print Collector/CorbisAs our earlier example shows, even with the rise of the scientific method, new theories often face resistance from established authorities and traditions, especially when the old beliefs appear to have some practical success.

Consider miasma theory. This idea, which goes back at least to Hippocrates, suggested that diseases were caused by foul airs, believed to originate from decomposing matter, or exhalations from plants and animals. Because it prompted health reforms in housing and sanitation, it led to fewer illnesses and thus became widely accepted, particularly in the polluted, overcrowded streets of Victorian London. However, it obscured the true cause of disease (bacteria), leading to many unnecessary deaths [sources: Science Museum UK; Sterner; UCLA].

In a rather ironic turn of events, one of London’s strongest advocates for miasma theory inadvertently helped to disprove it, at least in the case of cholera. William Farr, a pioneering epidemiologist and statistician, gathered crucial data during the 1854 cholera outbreak. John Snow famously used Farr's data to trace the origin of the outbreak to a contaminated water pump on Broad Street. This discovery, alongside the contributions of scientists like Ignaz Semmelweis and Joseph Lister, would later support Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch in proving germ theory. For now, it showcased the scientific method’s remarkable ability for self-correction [sources: BBC; Science Museum UK; UCLA].

4: Maternal Impression

The concept of maternal impression certainly led to some fascinating and bizarre tales.

ElenaVasilchenko/iStock/Thinkstock

The concept of maternal impression certainly led to some fascinating and bizarre tales.

ElenaVasilchenko/iStock/ThinkstockIt’s clear that medicine took its time earning a reputation as a serious and systematic discipline. One notorious example is Mary Toft, a woman in September 1726 who somehow convinced over a dozen doctors that she could give birth to deceased rabbits and their body parts. Repeatedly.

Let's take a moment to fully digest that.

Even though the scientific method had been firmly established in certain areas, medicine was still a hodgepodge of theories, often plagued with quackery and unfounded beliefs. The emerging field of heredity continued to accept maternal impression, the ancient notion that a pregnant woman's experiences—what she saw or felt—could physically affect her unborn child. In one particularly striking case, a newspaper reported that a father’s name “appeared in legible letters in his infant son’s right eye” [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Davis; Pediatrics; University of Glasgow].

Naturally, consulting experts concluded that poor Mary Toft must have had a traumatic, rabbit-related incident that somehow turned her into a baby-birthing machine for bunnies.

Toft managed to keep up the hoax for several months, becoming a national sensation, deceiving numerous doctors, and even catching the attention of King George I. Some experts, like German surgeon Cyriacus Ahlers, tried to disprove the fraud by presenting scientific evidence, such as the fact that some of the “newborn” rabbits had air in their lungs and their stool contained straw, grass, and grain. However, it wasn’t until someone caught her mother-in-law red-handed purchasing small rabbits and, under threat of painful reproductive surgery, that Mary admitted the truth [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Davis; Pediatrics; University of Glasgow].

3: Blood Will Out ... Eventually

Our understanding of blood and its functions has evolved dramatically over the centuries.

luchschen/iStock/Thinkstock

Our understanding of blood and its functions has evolved dramatically over the centuries.

luchschen/iStock/ThinkstockIf 18th-century physiology was in disarray, you can imagine how chaotic early medicine must have been. On one hand, access to dissection subjects led to significant strides in understanding anatomy and physiology as early as 300 B.C.E. On the other hand, every breakthrough was often met with opposition from superstition and societal bias.

Greek physician Praxagoras (fourth-century B.C.E.) was the first to distinguish between veins and arteries, but he mistakenly believed arteries carried air (likely because the arteries of cadavers were often empty). In the second century, Galen extended this theory, claiming that blood was produced in the liver, where it absorbed a “natural spirit,” before circulating through veins. Blood didn’t pump, it sloshed around the body, and once it mixed with the “vital spirit” from the lungs, it was consumed by organs, which he believed “attracted” it much like lodestone attracts iron. Blood, he also said, traveled to the brain through hollow nerves, where it absorbed an “animal spirit” [sources: Aird; Galen; West].

These beliefs endured until 1628, when William Harvey released his transformative work, "On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals." Prior to that, scholars like Arab intellectual Ibn an-Nafis, who passed away in 1288, had already made important corrections, yet his findings were unknown to the Western world. Another early contributor, Spanish physician Miguel Serveto, had accurately described circulation in the 16th century, but his conclusions were embedded within a religious argument, and like him, his works were eventually burned at the stake [sources: Aird; Cambridge Modern History; West].

2: Aristotle's Take on Physics

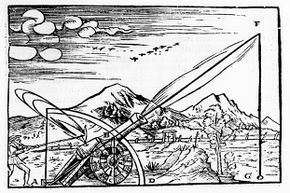

A 1561 engraving depicts a gunner firing a cannon, with the trajectory of the projectile displayed according to Aristotelian physics.

Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

A 1561 engraving depicts a gunner firing a cannon, with the trajectory of the projectile displayed according to Aristotelian physics.

Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty ImagesWhen Galileo overthrew the geocentric model, he also dismantled several other long-held (yet flawed) Aristotelian beliefs. Aristotle had posited that all matter had a designated position it sought to return to, and that heavier objects should fall faster than lighter ones. Through his precise experiments, Galileo demonstrated that all objects, regardless of weight, fall or roll downhill at the same constant rate, a phenomenon we now call acceleration due to gravity [sources: Alioto; Dristle].

Aristotle also maintained that a moving object in its natural state, such as a ball rolling on the ground, would gradually stop because it was naturally inclined to rest. However, as Galileo discovered, and Newton later codified, the perceived slowing of moving objects was actually caused by friction; remove that, and a ball would continue to roll indefinitely [sources: Alioto; Dristle; Cardall and Daunt; Galileo].

The Aristotelian-Ptolemaic perspective on physics suggested that a ball dropped from a ship's crow's nest would land some distance behind the mast, since the ship was moving forward while the ball fell. However, Galileo demonstrated that the cannonball, which shares the ship's velocity, would actually fall straight down to the base of the mast. Through this, Galileo, one of the pioneers of experimental science, anticipated Newton's laws of motion, the concept of reference frames, and disproved key arguments against Earth's motion [sources: Cardall and Daunt; Galileo].

1: Bloodletting as a Legit Medical Cure

Leeches may seem outdated, but are they really?

Leeches may seem outdated, but are they really?Any examination of the bizarre beliefs held before the advent of the scientific method would be incomplete without a mention of the strange and often terrifying medical practices that were once considered valid treatments.

Do you remember the whole idea of humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and choler, aka yellow bile)? Imagine the kind of medical treatments that could emerge from such a theory focused on bodily fluids, and you’d get a glimpse of what humoral medicine was like: diagnoses based on the scent of feces, urine, blood, or vomit; doctors prescribing forced vomiting, regular bloodletting, and questionable enemas to balance the body. While it lacked effectiveness, it certainly made up for it in life-threatening danger. Unsurprisingly, people often turned to prayer and folk remedies whenever they could [sources: Batchelor; Getz].

Some doctors once believed that bleeding hemorrhoids served as natural balancers of the body's humors, helping to alleviate conditions such as mania, depression, pleurisy, leprosy, and dropsy (edema). Of course, if the bleeding became excessive, the solution was to resort to red-hot pokers. It’s remarkable what people were willing to endure [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Encyclopaedia Britannica; DeMaitre].