On March 20, 1995, the Tokyo subway became the target of the deadliest bioterrorism event in modern history. Five men, each aboard different trains, punctured bags filled with liquid sarin using sharpened umbrella tips, releasing a deadly nerve gas into the air.

The aftermath was nothing short of catastrophic for postwar Japan. Commuters fell to the ground, blood foaming from their mouths. The streets outside the stations resembled a battlefield. By the time the chaos subsided, 13 people were confirmed dead and thousands were left wounded.

In the years that followed, rumors spread about terrorist groups planning chemical attacks in various cities. Bioterrorism fears have included anthrax outbreaks in the U.S. and concerns over ISIS possessing mustard gas. However, the 1995 Tokyo attack remains the deadliest ever carried out by a non-government entity.

This event ushered in a new chapter for Japanese society, one defined by a loss of trust and rising paranoia. It also reshaped the understanding of modern terrorism in the era of weapons of mass destruction. The lessons learned from that day continue to resonate with unsettling relevance today.

10. The Cult and the Chemical Weapon

In 1938, researchers at the IG Farben chemical company in Nazi Germany made a chilling discovery. They developed a new chemical, known as chemical 146, which wreaked havoc on the central nervous system, causing uncontrollable muscle spasms and ultimately death.

Within the perverse ideology of Hitler's Third Reich, the creation of such a weapon was seen as an achievement to be celebrated. Chemical 146 was soon renamed to honor the chemists responsible for its invention: Schrader, Ambros, Ritter, and Van der Linde. Its new name became sarin.

As the decades passed, sarin became infamous as one of the most lethal nerve agents known to mankind. During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein launched rockets filled with the deadly substance against his enemies, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths.

In one of the most horrifying incidents, sarin was used against the Kurdish town of Halabja, where nearly 5,000 people died in unimaginable agony. While this was a war crime, it also served as a horrific source of inspiration for future use of such weapons.

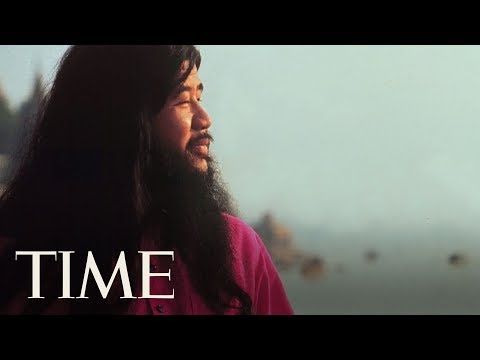

Thousands of miles away in Japan, the senior chemists of the Aum Shinrikyo cult took notice when sarin made the headlines. By the late 1980s, the group had begun researching weapons of mass destruction in preparation for their apocalyptic vision. Led by the blind guru Shoko Asahara, this cult was dedicated to bringing about the end of the world—and unlike most cults, they had the resources to try.

Over time, Aum Shinrikyo had successfully recruited scientists and wealthy backers from both Japanese and Russian circles. They poured millions into projects focused on germ warfare and the production of AK-47s. While they managed to grow some anthrax, many of these efforts ended in failure.

When sarin gained international attention, the cult seemed inspired. Abandoning their biological warfare programs, they redirected all their funds and efforts into developing sarin gas. By the early 1990s, their new doomsday weapon was ready for deployment.

9. The Guru and His Devotees

It’s important to understand exactly what kind of cult Aum Shinrikyo was. While they eventually became a doomsday group, they hadn’t originally set out with such a radical agenda.

Aum was founded by Shoko Asahara during the bubble economy era, a time when vast sums of money were easily made and spent on the most absurd things. The cult fused Christianity, Buddhism, yoga, and New Age philosophies with a heavy dose of pure madness.

At the core of the cult’s absurdity was Asahara himself. Claiming to be the reincarnation of the Hindu god Shiva, Asahara commanded a level of devotion from his followers that bordered on terrifying.

Members of Aum would consume vials of his blood or drink his dirty bathwater, believing it would lead them to enlightenment. Some even endured pain therapies so extreme they were later recognized as torture.

Despite the madness, the group was remarkably successful at attracting wealthy and influential members. Russians of means joined, and highly educated Japanese were drawn into Aum’s destructive pull. Asahara, in his delusion, seemed to think that his elite followers would give him control over Japanese society.

In 1990, Asahara orchestrated a plan where 24 of his followers ran for seats in the Japanese Diet. He was convinced they would win, seeing it as the first step in his political conquest of Japan. However, the public saw things differently—Aum’s party secured only 1,700 votes.

Following this electoral failure, Aum’s focus shifted toward triggering the apocalypse. In a disturbing sign of how lost its members had become, the cultists were so elated when they finally produced sarin that they composed a song to mark the occasion.

David Kaplan and Andrew Marshall report that one verse of the song went like this:

It came from Nazi Germany, A deadly little chemical weapon, Sarin, sarin. If you breathe in the mysterious vapor, You will collapse with bloody vomit pouring from your mouth, Sarin, sarin, sarin, The chemical weapon.

8. Preparing for the Attack

On the evening of June 27, 1994, as the Sun sank below the horizon, Yoshiyuki Kono had no idea that his life was about to spiral into a terrifying nightmare. A prosperous machinery salesman living in a quiet suburb of Matsumoto, Kono embodied the image of the successful Japanese professional. Then, at 11:00 PM, his wife suddenly fell gravely ill. In his panic, Kono dialed 119 (Japan's emergency number). That call would determine his fate.

What Kono didn’t realize was that his wife was experiencing the symptoms of sarin poisoning. Just moments before, Aum members had parked a modified van behind his house and begun releasing poison gas into the neighborhood.

The attack was a test run for the cult’s larger operation in Tokyo. Asahara was particularly interested in seeing how many lives they could take. After just 30 minutes, the entire area was gripped by terrifying convulsions.

By the time doctors arrived shortly after midnight, they found nearly 50 people wandering the streets, their noses running and their vision nearly gone. Inside the homes, others were writhing in convulsions, foaming at the mouth, or already dead.

It was a hot summer night, and many people had left their windows open before going to bed. That seemingly innocent choice would lead to their deaths. In total, seven people perished that night, while over 200 others became severely ill.

Aum saw their trial run as a success but realized they needed a more effective target for the next attack—one without proper ventilation, where no one could escape the poison cloud.

Yoshiyuki Kono became the main suspect in the case because he was the first to contact the authorities. He was arrested, and the media tarnished his name. As he recovered in the hospital and his wife slipped into a coma induced by the sarin, the entire nation of Japan turned against him.

Because of Aum's actions, Kono lost not only his beloved wife but also his reputation, career, and nearly his sanity.

7. The Attack Begins

On a clear spring morning, nine months after the Matsumoto attack, 30-year-old Kenichi Hirose boarded the Marunouchi Line of the Tokyo subway. In his hands, Hirose held an umbrella and a plastic bag containing two small packages.

It was rush hour, and the trains were packed with commuters heading toward the heart of the city. Unnoticed by anyone around him, Hirose calmly sat down amidst the chaos and waited.

At the same time, just after 7:30 AM, four other men boarded different subway trains across Tokyo. Toru Toyoda, Masato Yokoyama, Yasuo Hayashi, and Ikuo Hayashi, all carrying umbrellas and plastic bags, were headed to Tsukiji Station, deep within the government district. They all appeared to be waiting for something.

Shortly before 8:00 AM, the five men simultaneously let their packages fall to the floor of the carriages. With swift movements, they drove the tips of their umbrellas into the bags, puncturing them.

They then rose to their feet, pushed their way through the crowd, and disappeared into the morning rush. As the trains continued to their next stops, no one noticed the small pools of liquid beginning to form beneath the punctured bags.

In a strange twist of fate, the first clue that something was amiss didn’t come from any of the innocent passengers in the subway cars, but from Kenichi Hirose. As soon as he entered the getaway car, his body began to shake violently. His breath hitched in his chest, and he struggled to speak, his mouth failing to form any words.

Despite the careful precautions taken by Aum, Hirose was the first victim that morning to show symptoms of sarin poisoning. Unfortunately, he would not be the last.

6. The Onset of Panic

Within moments of the bags being punctured, it became undeniable that something was terribly wrong. On the Hibiya Line train, which had been poisoned by Yasuo Hayashi, passengers began coughing uncontrollably.

By 8:02 AM, many had collapsed onto the floor, vomiting. Others clutched their eyes in excruciating pain. As the train reached Kodemmacho Station, a passenger kicked the bags filled with sarin onto the platform. It was then that the situation took a dramatic turn for the worse.

Three subway lines were clearly impacted, but no one had any clue about what was happening. A rumor quickly spread that there had been an explosion in the Tsukiji area of the government district, possibly due to a terrorist attack.

The operators pulled several trains out of service. Unfortunately, some of these trains, stopped at platforms, were contaminated with sarin. As the doors opened, toxic fumes flooded out, exposing commuters. For those trains left in place, the passengers remained trapped inside, breathing in the deadly gas.

Kazuyuki Takahashi was one of the unfortunate individuals caught in the chaos. He boarded the Hibiya Line train at Hatchobori, only to find his fellow passengers lying unconscious, their bodies convulsing in spasms.

The doors shut, and he was forced to continue his journey on the contaminated train until it reached the next station. By the time he managed to get off at Tsukiji, he was already suffering from the lethal effects of sarin poisoning.

At Kasumigaseki, three subway workers—Toshiaki Toyoda, Kazumasa Takahashi, and Tsuneo Hishinuma—were tasked with removing suspicious plastic packages from a train. They completed their job without any protective gear, simply wrapping the sarin-soaked plastic in newspaper.

Within minutes, Toyoda was struck with severe illness. He later recounted that he turned around just in time to witness Takahashi and Hishinuma collapse, blood foaming from their mouths. Aum’s lethal assault had claimed its first two victims.

5. Apocalypse Now

For those trapped underground, it must have felt as if Asahara’s long-awaited apocalypse had finally arrived. The sarin gas drifted through the subway tunnels, spreading to the platforms. It clung to survivors’ clothes and continued to harm others as they rushed to escape. By 8:30 AM, the transport network had ground to a halt, but the death toll kept rising.

The effects of sarin make for unsettling reading. Some began to vomit uncontrollably, while others fell into comas from which they would never awaken. For many, their eyes were the greatest source of torment.

Sarin causes the pupils to constrict to the size of pinpricks. For those affected, it seemed as though the sun had been dimmed, making even a bright spotlight appear like a faint bulb. Many who were affected went permanently blind. In one horrific case, a woman’s contact lenses fused to her eyeballs, and doctors had to surgically remove both of her eyes.

Other victims were left paralyzed or wracked with violent convulsions. With the cause still a mystery, many of those who rushed in to help were poisoned as well. Paramedics treating the victims found their hands trembling uncontrollably.

Outside the affected stations, the bodies of the ill and injured began to accumulate. Central Tokyo took on the appearance of a war zone. Traffic came to a standstill. Hospitals were overwhelmed. It felt as though the end of the world was upon them.

4. The Attack Unravels

At that very moment, many miles away, Hiroshi Morita was preparing to publish his report on the earlier Matsumoto attack. A doctor who had treated victims at the scene, he was now regarded as Japan’s foremost expert on sarin poisoning.

By a stroke of luck, he happened to have the television on when the first reports from Tokyo started coming through. Morita instantly recognized what had happened and knew exactly what needed to be done.

It’s hard to emphasize just how unprepared Tokyo was for a nerve gas attack. Even though it was one of the largest cities on Earth, it was still common to leave your bike unattended on the street. No one was ready for any kind of attack, let alone one involving Nazi-style weapons of mass destruction.

When the first victims of sarin arrived at the hospital, complaining of blindness, the nurses coldly instructed them to visit an eye specialist. Given that the first few hours of sarin poisoning are critical in determining whether a person recovers or sustains lasting damage, this approach could have been catastrophic. Fortunately, Hiroshi Morita was there to assist.

As the attack unfolded, Morita urgently called the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. When they seemed uninterested in his diagnosis, he quickly assembled a team of colleagues. Using Morita’s freshly completed report on treating sarin victims, they began calling every hospital in Tokyo, instructing them step-by-step on how to respond.

It was a crucial turning point in Japan’s day of terror. Thanks to Morita’s swift actions, hospitals immediately began treating anyone showing symptoms of sarin poisoning. While the day’s casualties were tragic, without Morita’s quick thinking—or if Aum hadn’t previously tested their sarin in Matsumoto—the death toll could have been far higher.

3. The Aftermath

Despite causing an unprecedented number of injuries, Aum's sarin attack was ultimately a failure. Just weeks later, Timothy McVeigh would use a truck bomb to kill nearly thirteen times as many people in Oklahoma. Outside Japan, his actions overshadowed most of the media coverage surrounding Aum.

Just five years later, 9/11 would redefine how we perceive terrorism. Even before his trial ended, Asahara was already viewed as a relic—a self-important yoga instructor who had attempted and failed to carry out the deadliest terrorist attack in history.

Nevertheless, Japan continues to bear the emotional scars of the Tokyo subway attacks. As novelist Haruki Murakami put it, March 20, 1995, was the day that 'Japan's psyche changed forever.' The optimism of the bubble years faded away for good, replaced by a deep sense of self-doubt and paranoia, leaving the nation feeling adrift in a violent and uncaring world.

This trauma was exacerbated by the police's failure to apprehend all of the suspects. As late as 2012, two of the attackers remained at large. The last to be captured was Katsuya Takahashi, who had served as a getaway driver during the attack. He was discovered living and working in Tokyo, and his trial wasn't concluded until 2015. By March 2016, no executions had been carried out. Many of Asahara's victims are still waiting for his death.

One of the most profound shifts in postwar Japan was its evolving relationship with religion. In the years leading up to the war, the empire's enforcers often targeted organized religious groups. However, with the start of reconstruction, a combination of guilt and the desire to move forward meant that religious institutions were largely left unmonitored by the police. In fact, authorities even ignored tips in 1994 linking Aum to the Matsumoto attack.

In stark contrast, Japan today has become notably hostile to religion. Many people now view it as a negative influence. A telling example of this shift is when smartphone companies started blocking harmful websites for children's phones, they included religious sites alongside gambling and adult content.

Although Asahara failed to accomplish his goal of destroying the Japanese government, he and his followers undeniably altered the course of the country, leaving a lasting and troubling impact that remains felt today.

2. The Disintegration of a Deadly Cult

Just two days following the attack, the police launched a series of large-scale raids on two Aum compounds. Key members of the cult were arrested, a sarin production facility was dismantled, and the group’s operations were thrown into disarray.

By early May, authorities had tracked down Asahara, concealed in a hidden chamber within the Aum headquarters. The mastermind behind the sarin attacks was apprehended. He denied any involvement in the subway bombings, marking what would likely be his last intelligible statement.

Despite the progress the police had made, Aum was resolute in its decision to retaliate. With 40,000 active members, vast resources, and access to deadly weapons, it was inevitable that they would seek revenge.

Their initial act of vengeance occurred just days before Asahara's capture. A cyanide-laden bomb was left in a restroom at Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, positioned directly beneath a ventilation shaft. The bomb contained enough poison to render the sarin attack almost trivial by comparison.

Experts later calculated that the bomb contained enough cyanide to kill 10,000 people. Fortunately, a malfunction in the detonation mechanism caused the bomb to catch fire instead of exploding. Authorities extinguished the flames before they could set off a chain reaction and release the toxic gas.

Subsequent attempts were smaller in scale but equally threatening. Bombs were sent to Japanese officials, causing severe injuries to at least one person. More gas attacks were also being prepared. However, it was too late. Asahara and 12 others were sentenced to death, bringing the group's reign to a definitive end.

In 2000, the surviving leadership of Aum distanced itself from the imprisoned Asahara. The cult established a fund to compensate the victims, rebranded itself as Aleph, and asserted its renunciation of violence.

Once a massive group at its peak before 1995, the membership of Aum dwindled to just 1,500. By 2016, these remaining members continued to be under close surveillance by the Japanese authorities.

1. The Final Toll

By early afternoon, Tokyo had managed to regain control of the situation. Doctors throughout the city were swiftly treating those affected by sarin poisoning. News broadcasts urged anyone experiencing even slight vision impairment to seek medical attention immediately. The affected subway lines were shut down. Decontamination teams were dispatched to handle the cleanup.

By this point, it was evident that Aum's goal of bringing about Armageddon had failed. Despite the chaos caused by their attack, Tokyo was already on the path to recovery.

In the meantime, the organization was in turmoil. Several attackers had unintentionally poisoned themselves while releasing the sarin gas. It had already become clear that Yoshiyuki Kono of Matsumoto was not behind the gas attack in Tokyo either.

The police were actively searching for the culprits, following anonymous tips that pointed to the group. Through their deranged actions, Aum had managed to bring about their own version of an apocalypse.

Nonetheless, the attack left an indelible scar on Tokyo’s citizens. As the sun set on the bloodiest day in the city's postwar history, it was revealed that 12 people had died, and thousands more were wounded. Common estimates placed the number of injured between 5,000 and 6,000. Only 9/11 resulted in more hospital admissions from a single terror attack.

Even now, many continue to suffer the effects of Aum's actions. Sarin poisoning can have long-term consequences. Sanae Yama was hospitalized on the day of the attacks, and four years later, the smell of paint thinner triggered a severe sensitivity to chemicals that she still endures. When the Financial Times interviewed her in 2005, she described herself as a prisoner in her own home, unable to even tolerate the smell of aftershave without vomiting.

For some, the long-term effects have included blindness, physical weakness, and even death. Years after the attack, one victim succumbed to injuries related to the incident, increasing the death toll to 13.

In addition to the physical effects, there were significant mental consequences. A 2000 study revealed that up to 30 percent of those affected by the attack were still grappling with mental health issues. Due to Japan's rigorous work culture, some of those permanently disabled by the poisoning later lost their jobs.