On April 26, 1986, a catastrophic explosion took place at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in northern Soviet Ukraine, an incident now globally recognized as the Chernobyl disaster.

On the evening of April 25, engineers committed several critical errors, such as deactivating Reactor No. 4’s emergency safety mechanisms and its power-regulation systems. At 1:23 AM, the reactor’s power levels spiked, triggering a chain of events that resulted in an explosion, releasing over 50 tons of radioactive substances into the air.

In the subsequent days, 32 individuals lost their lives at Chernobyl, with countless others suffering from radiation burns. Approximately 8.4 million inhabitants of Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia were exposed to the radioactive fallout. This tragedy is regarded as the worst nuclear power plant accident in history, and the affected region continues to grapple with its consequences.

10. Radiation Levels Post-Explosion Were Unprecedented

Shortly after the explosion, helicopters were deployed over Reactor No. 4 to assess radiation levels. Specialists couldn’t obtain precise measurements because, at 200 meters (656 ft) above the reactor, radiation had soared to 1,500 rems, exceeding the 500 rems limit of their equipment.

To mitigate the catastrophe, helicopters dropped 40-kilogram (88 lb) lead slabs onto the reactor, followed by tons of sand designed to absorb radiation. However, the operation faced challenges due to the unprecedented scale of the disaster. Pilot Alexander Petrov, who was on the scene, remembered, “It took over 24 hours to get organized. [ . . . ] Initially, our commanders were unsure how to proceed. We flew out to assess the situation, returned, and went back the next morning.”

9. Delayed Evacuation

The Chernobyl disaster released 50 million curies of radiation into the atmosphere—equivalent to the impact of approximately 500 Hiroshima bombs. While police patrolled the streets in gas masks, residents remained uninformed, relying only on rumors. Armen Abagian, then director of a Moscow nuclear research institute, urged the Soviet government to evacuate Pripyat without delay. He recounted, “Children were playing in the streets; people hung laundry out to dry, unaware of the radioactive environment.”

Panic set in among residents when they noticed a “metallic smell” in the air and an unusual change in the atmosphere. By midnight on April 26, an evacuation order was issued, and 1,200 buses and 200 trucks were used to relocate 47,000 residents of Pripyat. The locals believed they would return home soon, but that day never came.

8. Radiation Contamination Reaches Other Nations

The buses used to evacuate Pripyat’s residents inadvertently spread radiation to broader areas. The evacuation lasted hours. One resident described the scene: “Lines of packed buses left the city, one after another, like giant beetles stretching for kilometers. The traffic was chaotic, reminiscent of scenes from the Second World War.”

Shortly after the initial catastrophe, shifting winds carried high levels of radiation toward Kiev, the Ukrainian capital. Despite this, the city proceeded with its annual May Day parades, as authorities reassured citizens that all was well. It wasn’t until 11 days after the disaster that officials advised Kiev residents to avoid consuming leafy vegetables and to remain indoors.

Later in May, Russia’s first deputy health minister debunked the myth that vodka and red wine could cure radiation exposure. Over 500,000 residents in Ukraine were eventually compelled to abandon their homes.

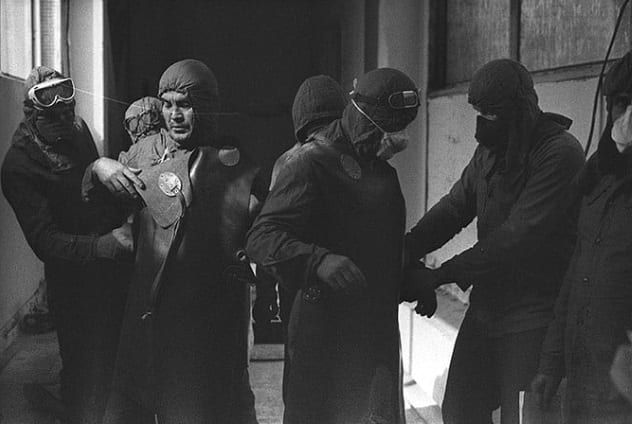

7. Military Reserves Crafted Their Own Protective Gear

Since the cleanup efforts began in 1986, more than 600,000 civilian and military personnel have been honored as “Chernobyl liquidators.” Initially, robots from West Germany, Japan, and Russia were deployed to clear debris, but they malfunctioned due to extreme radiation levels. The task was then assigned to humans, who could only work in the area for a maximum of 40 seconds at a time.

Most liquidators were military reserves, and the army lacked adequate uniforms for operating in radioactive environments. To compensate, reserves fashioned their own protective gear, using lead sheets up to 4 millimeters thick as aprons to shield their spines and bone marrow. Photographer Igor Kostin noted, “The resourceful ones even added a vine leaf for added comfort.”

Many liquidators have since experienced severe health issues, some of which proved fatal.

6. Doctors Confronting Death

Dr. Robert Peter Gale, dubbed “the Chernobyl Doctor,” was among the numerous physicians and scientists from 15 countries who assisted in the disaster’s aftermath. Dr. Gale treated patients with such extreme radiation exposure that even bone marrow transplants were ineffective. Without functioning bone marrow, patients typically succumbed within four weeks. Assessing radiation exposure was also challenging, as the only visible symptoms were gradual hair loss and slight skin darkening.

In 1986, Dr. Gale and the director of the Soviet Union’s Central Institute for Advanced Medical Studies agreed to monitor the 100,000 individuals living within the “danger zone”—a 30-kilometer (18.7 mi) radius around the site, later known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. He remarked, “Doctors confront life and death daily, but death is a biological event for us. We rarely ponder our own mortality. Chernobyl forced me to reflect on my own mortality—and on humanity’s fragility. Sadly, it often takes such tragedies to bring this realization.”

5. The Submerged Villages

The village of Kopachi, located 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) from the Chernobyl disaster site, is a haunting and abandoned place. The Soviet Army bulldozed and buried its homes, but this strategy backfired.

Chernobyl guide Yuri Tatarchuk explained, “Kopachi was severely contaminated, so the decision was made to bury it, house by house. While it seemed logical at the time, it worsened the situation. Digging pushed radioactive material deeper into the soil and closer to the water table, spreading contamination even further.”

Today, only two structures remain, including the former kindergarten, where children endured 36 hours of exposure before evacuation. Tatarchuk reflected on the aftermath, “It was a crime. [ . . . ] At least 5,000 people suffered severely, and pregnant women were advised to undergo abortions. It was a brutal period.”

4. Chernobyl’s Puppies

Contrary to the myth that Chernobyl is lifeless, over 900 stray dogs are estimated to inhabit the Exclusion Zone. Many roam the abandoned cooling tower of the former power plant. These puppies are thought to be descendants of pet dogs abandoned by their owners, who were given only a few hours to evacuate and instructed to take only essential items and limited food.

The dogs have been forced out of the forests by wild wolves that dominate the area. Volunteers, including veterinarians and radiation specialists, have established the nonprofit Dogs of Chernobyl. The dogs are tagged, their radiation levels monitored, and they are studied for diseases like rabies. Some wear radiation sensors and GPS receivers, helping map radiation levels across the exclusion zone.

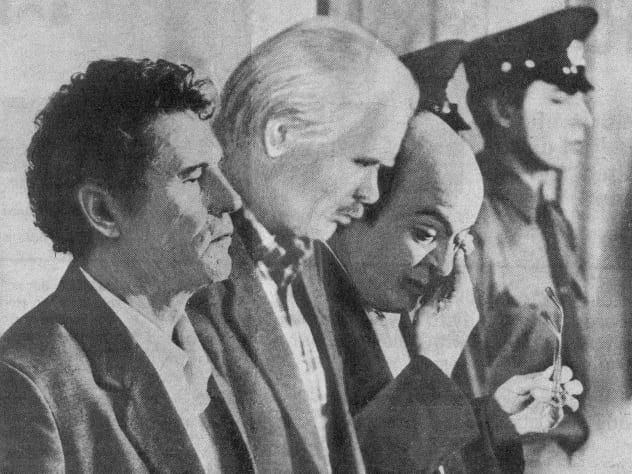

3. Chernobyl Executives Sentenced to Labor Camps

In July 1987, Chernobyl’s plant director Viktor P. Bryukhanov, chief engineer Nikolai M. Fomin, and deputy Anatoly S. Dyatlov were sentenced to two to ten years in a labor camp. They were convicted of severe safety violations that caused an explosion. Judge Raimond Brize stated in court, “The plant operated in an environment of negligence and irresponsibility.” The officials were also condemned for delaying the evacuation of Pripyat.

Today, the damaged fourth reactor is encased in an old sarcophagus, with the New Safe Confinement (NSC) structure built over it. Despite more than 30 years passing since the Chernobyl disaster, its repercussions continue to affect many lives.

2. Radiation-Affected Wildlife

Months after the Chernobyl disaster, radioactive contamination reached Galsjo Forest in Sweden. Elk were found to be contaminated, and the process of discarding their bodies in a quarry after removing their heads and fur was documented.

A 10-square-kilometer (4 mi) area of forest near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant earned the name “Red Forest” after radiation caused the trees to perish and their leaves to turn a vivid red. Following the evacuation of humans, wildlife flourished due to the lack of predators—wild boar populations increased eightfold within two years. Radioecologist Sergey Gaschak noted, “Animals appear unaffected by radiation and inhabit areas regardless of contamination levels.”

The Red Forest remains one of the most contaminated places globally, with over 90 percent of radioactivity concentrated in the soil. Research on mouse embryos revealed they disintegrated under these conditions, and horses within 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) of the plant perished due to thyroid gland failure.

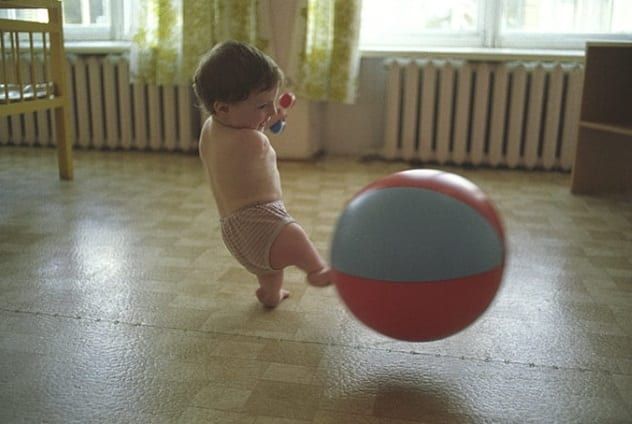

1. Birth Defects in Chernobyl’s Children

After the disaster, residents in Kiev were instructed by officials to take frequent warm showers, keep windows shut, and clean their furniture regularly. Despite these measures, doctors have observed an increase in birth defects since 1986. Belarus, which borders Ukraine and is near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, saw UNICEF report in 2010 that 20 percent of its adolescents suffer from chronic illnesses or disabilities linked to birth defects.

Numerous charities support facilities caring for babies born with severe birth defects, such as neurological disorders and heart conditions. Microcephaly, where a baby’s head is disproportionately small, is also a common defect in the region.

In 2014, Michael Donnelly, chairman of Chernobyl Children’s Appeal, stated, “These children endure suffering through no fault of their own. [ . . . ] The situation remains unchanged from 28 years ago. Radiation levels in the Chernobyl zone are as high today as they were in 1986.”