Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) pose a significant challenge worldwide. However, some of the most unethical experiments have resulted in meaningful advancements in STI treatments.

At some point, it becomes necessary for a human to test experimental treatments to drive progress in medical research for STIs. The risks involved often contradict the Hippocratic Oath, which demands that physicians “utterly reject harm and mischief.” This article explores instances where ethics were heavily compromised, yet there remained a glimmer of hope for improving STI treatment.

10. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The Tuskegee syphilis study took place over 40 years, from 1932 to 1972, in Macon County, Alabama. The experiment involved 399 African American men suffering from syphilis and 201 healthy men. The participants were never informed about the true nature of their conditions, instead being told they had “bad blood” and that their treatment would last six months. In exchange for their participation, they received free food, healthcare, and burial insurance.

By the mid-1940s, penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis. However, the researchers kept the participants unaware of the drug’s effectiveness and continued to explore other treatments. As the 1960s progressed, mounting criticism behind the scenes grew. Peter Buxtun, a venereal disease investigator for the US Public Health Service, became a vocal critic. When he filed an official complaint, he was told that the study had to continue until its completion, which would likely mean until all participants had died and their bodies had been autopsied.

The study finally ended in 1972 when Buxtun exposed the details to the press. At that point, only 74 of the original 600 participants were still alive. Additionally, 40 of their spouses contracted syphilis, and at least 19 children were born with the disease.

9. Dr. Heiman’s Gonorrhea Experiment

Over 40 reports of experimental gonorrhea infections in humans exist from around the turn of the 20th century. This practice diminished somewhat after it was discovered that monkeys could also be infected with the disease.

At its peak, one widely used method involved applying a gonorrhea sample to the tip of a stick and swabbing it into a victim’s eye. In 1895, Dr. Henry Heiman used this technique to intentionally infect two mentally disabled children and a man suffering from the advanced stages of tuberculosis. In his personal accounts, Heiman described the four-year-old child he experimented on as “an idiot with chronic leprosy” and the 16-year-old boy simply as “an idiot.”

Heiman devoted a significant portion of his career to studying hypersensitivity reactions to vaccines, known during his time as the Pirquet reaction. As with many of the unethical experiments conducted by early medical practitioners, the hoped-for outcome was likely a form of safe immunization.

8. The Willowbrook School Hepatitis Study

Willowbrook State School was far from an ideal environment for children. However, in Staten Island, New York, it was one of the few institutions available for the care of the mentally disabled. Overcrowding and deteriorating conditions by the mid-1950s resulted in most students contracting a form of hepatitis. As a consequence, Dr. Saul Krugman, a leading hepatitis researcher, took an interest in the school, dedicating the next two decades to studying the disease among the infected students.

The overcrowding issue and the need for parental consent in Krugman’s studies were eventually addressed in a disturbingly efficient—yet unethical—manner. In 1964, the main school was closed to new admissions, as it was over 2,000 students beyond capacity. From that point, the only available placements were in the hepatitis unit, where students were deliberately infected. Parents had little option but to give consent.

Krugman defended his actions by stating that the infection rate at the main school was already so high that new students would likely contract hepatitis regardless. His research led to the identification of two strains of hepatitis: A and B. He also discovered that the transmission methods differed, paving the way for the development of a successful hepatitis B vaccine.

7. The AIDS Drug Overseas Placebo Trials

In the 1990s, the US Centers for Disease Control sponsored experiments in Africa, Thailand, and the Dominican Republic to test the effectiveness of a drug known as AZT. In the US, AZT was administered to pregnant women with AIDS during the last 12 weeks of their pregnancy.

AZT was intended to reduce the risk of mother-to-child transmission of AIDS. However, at the time of the trials, the drug cost $1,000 per mother for treatment. The overseas experiments aimed to determine whether a more affordable treatment could be found. A total of 12,211 women participated in the trials, with some receiving the same dosage as American mothers, others receiving a reduced dose, and some receiving a placebo.

The ethical validity of the AZT experiments has been a subject of intense debate. Supporters argue that the women who received the placebo would not have had access to the costly medication anyway. However, the troubling gray area of the study lies in the fact that over 1,000 infants were infected by mothers who participated in the trial. These mothers were unaware that the medication they were taking was ineffective.

The trials concluded after their completion in Thailand. The results showed that a shorter duration of AZT treatment still significantly reduced the likelihood of babies being born with the infection.

6. Dr. Black’s Herpes Experiment on a Baby

In the late 1930s, Dr. William C. Black initiated a series of herpes experiments. In total, 23 children were deliberately injected with the virus to study the physical symptoms it caused. In 1941, he infected a 12-month-old infant, whom Black controversially claimed had been “offered as a volunteer.” In the best-case scenario, this was an unusually communicative baby.

The results of his experiments were submitted to The Journal of Experimental Medicine. The journal's editor, Dr. Payton Rous, responded by stating, “In my personal view, the inoculation of a twelve-month-old [ . . .] was an abuse of power, an infringement of the rights of an individual, and not excusable because the illness which followed had implications for science.”

Despite facing significant criticism, Dr. Black’s study was instrumental in revealing that the symptoms of the herpes virus can differ widely between patients. His research was published in The Journal of Pediatrics in 1942.

5. Dr. Noguchi’s Syphilis Experiments

Dr. Hideyo Noguchi is most well-known for his syphilis experiments conducted on humans in 1911 and 1912, which were part of his broader research at the Rockefeller Institute in New York.

Noguchi enlisted 571 individuals from local hospitals and clinics, including orphans. Of these, 315 were already infected with syphilis, while the remaining participants were syphilis-free at the start of the study. The hospitalized subjects were also undergoing treatment for other diseases, such as leprosy, malaria, pneumonia, and tuberculosis.

The experiments involved injecting subjects with syphilis extracts and observing the skin reactions. The syphilis-free participants were vital to the study, as the extracts triggered distinct reactions depending on whether the person was already infected.

The experiments drew significant public criticism and sparked protests. One of Dr. Noguchi's colleagues at the Rockefeller Institute, Jerome Greene, responded by claiming that Noguchi had injected himself with the extract before using it on others, proving it couldn’t cause infection. This was later debunked as false. Although Noguchi did inject himself, he was diagnosed with syphilis in 1913 after neglecting symptoms for an extended period.

Through his research, Dr. Noguchi uncovered that syphilis leads to progressive paralysis, and for this, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize.

4. Experimental Hepatitis E Vaccine Tested On Nepalese Army

It’s important to note that, unlike hepatitis B, C, or D, hepatitis E is not typically spread through sexual contact. Instead, it is transmitted through oral-fecal interaction, so it’s best to avoid such exposure.

Between 2001 and 2004, a clinical trial was conducted by GlaxoSmithKline and the United States, involving 1,794 members of the Royal Nepalese Army. Due to contaminated water supplies, Hepatitis E is prevalent in many parts of Asia and Africa. The trial aimed to assess the effectiveness of a new vaccine.

The participants were divided into two groups. One group received a placebo vaccine, with seven percent of them showing symptoms related to Hepatitis E during the study. In contrast, only 0.3 percent of the group receiving the actual vaccine developed symptoms of the disease.

Jason Andrews from Yale School of Medicine has been outspoken in his critique of the trial. He believes that the participants might have been easily coerced into taking part. More generally, he criticized GlaxoSmithKline for deciding not to mass-produce the vaccine despite its proven effectiveness.

It took three years for the trial results to be published, which further suggests that the focus of the research may have been more profit-driven than centered on public health.

3. The Guatemala Syphilis Experiments

The Guatemala syphilis experiments took place between 1946 and 1948. These were conducted by the US government, with the collaboration of certain Guatemalan health authorities.

The primary goal of the experiments was to evaluate the effectiveness of penicillin in treating syphilis. To carry out the study, Guatemalan prostitutes who were infected with the disease were targeted, alongside the men they subsequently infected. However, the majority of the victims were deliberately infected with the disease. They were mostly prisoners and psychiatric patients. As is often the case, society’s most vulnerable were exploited for medical research.

In total, 1,300 individuals were intentionally infected with syphilis, gonorrhea, or the lesser-known STI, chancroid. Of these, only 700 received any form of treatment. The documented number of deaths was 83, though the actual death toll was likely much higher. Dr. John Charles Cutler oversaw the experiments, and he was also a key figure in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study.

In 2010, the United States formally apologized to the Guatemalan victims of the experiments, calling their treatment “outrageous and abhorrent.”

2. GlaxoSmithKline’s AIDS Drug Trial On Orphans

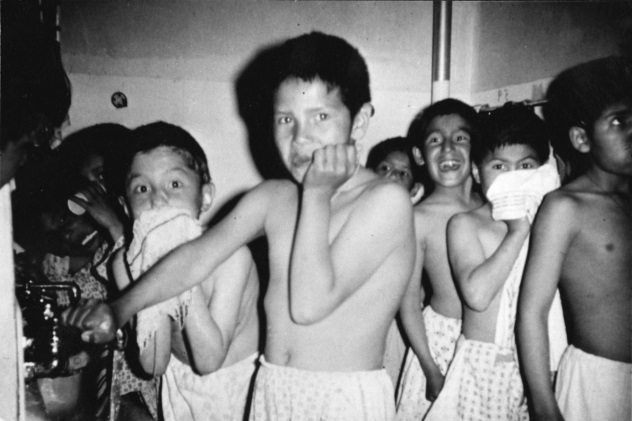

In 2004, it was uncovered that GlaxoSmithKline and the National Institutes of Health had funded medical experiments on orphans and other vulnerable children. These trials were conducted at the Incarnation Children’s Center in New York and had been ongoing for at least nine years.

Typically, parental consent is required for children to take part in medical studies. However, because of the children's unique situations, New York authorities gave consent on their behalf. Some of the children were as young as six months old.

The children were used as test subjects for various medications throughout the years. This included trials of herpes treatments and the powerful AZT drug for AIDS and HIV, which is known to be extremely strong, even for adults.

Doctor Nicholas, a pediatrician involved in the trials, claimed, “No child ever had an unexpected side effect.” This may be true from the perspective of the researchers, but the children’s own expectations were consistently betrayed.

1. The Ugandan AIDS Drug Trial

Nevirapine, sold in the United States under the brand name Viramune, is a medication used to treat and prevent AIDS. In 1997, trials for the drug began in Uganda to assess whether a single-dose treatment could prevent mother-to-child transmission of the disease. Single dosing was also essential for safety, as prolonged use of nevirapine is known to cause liver damage. It’s an exceptionally strong drug.

The trial’s results confirmed the drug’s effectiveness in reducing disease transmission, and in 2002, President George W. Bush’s administration funded a $500 million initiative to distribute the drug across Africa.

However, it was later revealed that the trial’s organizers had been concealing critical information. Specifically, 14 participant deaths went unreported, as well as thousands of adverse reactions. In 2002, the Ugandan government was made aware of these disturbing facts, and the trial was subsequently halted. The drug’s manufacturer, Boehringer Ingelheim, also withdrew its application to use nevirapine on American infants.