Owing to humanity's natural inclination to categorize things through seemingly random criteria, often influenced by Eurocentric viewpoints, the diverse cultures of the Americas are defined by the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492. That being said, here are 10 captivating pre-Columbian cultures.

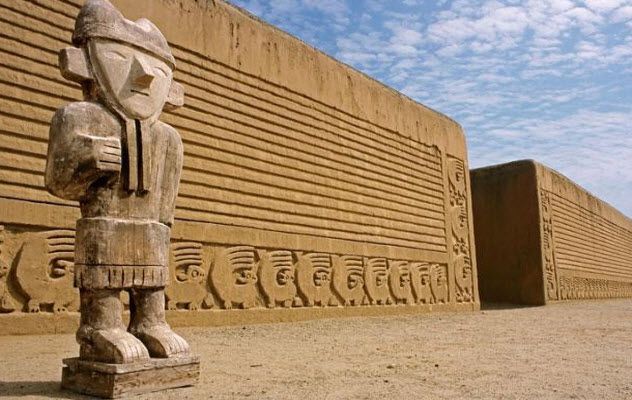

10. Chimu Civilization

The Chimu culture, which dominated much of northern Peru, is believed to have emerged around the 10th century AD. Likely descended from remnants of the Moche culture, which thrived in the region centuries earlier, the Chimu created one of South America's most remarkable archaeological sites: their capital city of Chan Chan, the largest pre-Columbian city on the continent. Sadly, this once-great city is now uninhabitable due to severe water shortages. (A vast network of canals had provided water for the Chimu inhabitants.)

While much of their culture stemmed from their remarkable agricultural skills, partly due to their mastery of irrigation systems, the Chimu were also adept metalworkers, particularly with gold and silver. Their pottery is known for its distinctive appearance, featuring a shiny black finish, a result of firing the clay at high temperatures in a sealed kiln.

However, as often happens with smaller civilizations, the Chimu were eventually absorbed by their more powerful neighbor, the Incas. Between 1465 and 1470, multiple invasions by the mighty Incan emperor Pachacuti and his son Topa (also known as Tupac) brought an end to Chimu independence, and the culture gradually disappeared.

Regarding their religious practices, one of the Chimu's most significant deities was Si, the Moon goddess. Associated with the production and distribution of food—believed to be linked to rainfall and the reproductive cycles of marine life—she was honored with various offerings, including human sacrifices. This stood in contrast to the Incas, as the Chimu's worship of the Sun was secondary to their reverence for the Moon.

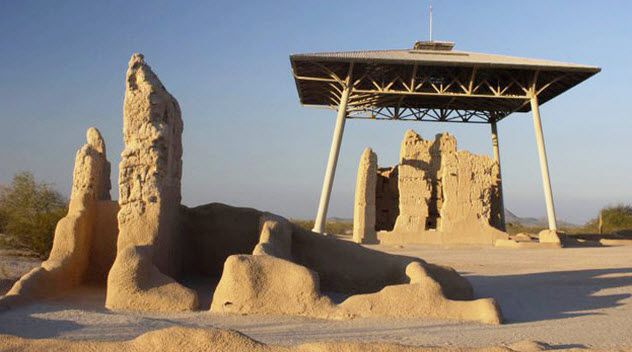

9. Hohokam Civilization

The name Hohokam, believed to be derived from the Pima word for “those who have vanished,” reflects the fact that this people no longer exist. The Hohokam, who primarily lived in what is now Arizona, emerged around AD 200 and lasted for more than a thousand years until their disappearance around the 15th century. Their history is typically divided into four phases: Pioneer (200–775), Colonial (775–975), Sedentary (975–1150), and Classic (1150–1450).

Similar to the Chimu in South America, the Hohokam were exceptional engineers when it came to irrigation. In fact, they were the foremost canal builders in pre-Columbian North America. (Mormon pioneers later utilized their canal system when settling the area near Mesa, Arizona.) Their remarkable engineering skills allowed them to sustain a larger population compared to the hunter-gatherer tribes that were also present at the time.

Snaketown, a key trading site along the Gila River, stands as one of the Hohokam’s largest villages and was the first of their settlements to be excavated. Archaeologists discovered one of the biggest courts ever found there, used by Mesoamericans for their famous ballgame.

8. Chachapoya Civilization

Known as the “cloud people” by the Incan conquerors, the Chachapoya of northern Peru flourished from around the eighth century AD until their conquest by Inca king Topa, shortly before the arrival of the Spanish. Though the Chachapoya were renowned for their fierce warrior culture and impressive architectural skills, much about their civilization remains a mystery.

One of the few discovered sites, the ancient walled city of Kuelap, was likely the capital of the Chachapoya and stands as the largest stone structure in South America, even surpassing Machu Picchu. Construction of Kuelap began around the sixth century, and its massive stone walls enclose a site that stretches 600 meters (2,000 feet) in length and 110 meters (360 feet) in width. It is estimated that between 3,000 and 4,000 people may have lived there.

Unlike many of their neighbors, the Chachapoya seem not to have had a particular affinity for gold or silver, as no artifacts containing these precious metals have been discovered. However, they were highly skilled in weaving and pottery, with beautiful examples of textiles often found alongside their mummified remains.

Moreover, nearly their entire population was decimated by diseases brought by the Spaniards, with some estimates suggesting as much as a 90 percent loss. Due to the scarcity of firsthand accounts, one aspect of their heritage has sparked much debate. Spanish and Incan contemporaries described the Chachapoya as 'tall and fair-skinned,' leading some to theorize that they might have been descended from groups ranging from the Vikings to the lost tribes of Israel.

7. Huastec Civilization

Many consider the Huastec of northern Mexico to be an offshoot of the Maya (although not necessarily directly from the Mayan civilization), with their emergence dating back to around 1000 BC, though their exact origin remains uncertain. According to their myth, the first Huastec people arrived by sea, settling in a place called Tamoanchan, though its precise location is lost to history. This could explain why the Huastec were such proficient fishermen, using large nets and clay weights to aid in capturing sea creatures.

One of the discovered sites is Tamtoc, which was first settled around 900 BC and continued to be inhabited until just before the 16th century AD. Situated in north-central Mexico, Tamtoc was a significant pre-Columbian urban center, covering an area of over 900 acres.

The most remarkable find at the site is the Monument 32, also known as the Tamtoc calendar stone. Featuring intricate imagery thought to represent, among other things, the lunar cycle, the stone demonstrates that the Huastec had a solid understanding of astronomy. Renowned for their agricultural and trading skills, the Huastec remained independent for centuries until their conquest by the Aztecs in the 1300s. Spanish visitors later noted that the Huastec typically did not wear clothing.

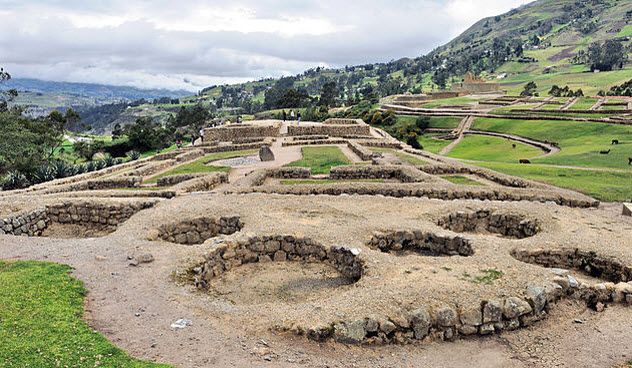

6. Canari Culture

The Canari civilization, known for their ferociousness in battle, thrived in southern Ecuador from AD 500 until their subjugation by the Inca Empire in 1533 under the rule of Huayna Capac. The Canari fought fiercely against the Incas, and as a result, they were punished harshly by the Incan forces, being relocated to more remote areas than any other conquered tribe. Just prior to the Spanish invasion, the Canari were blamed for their involvement—or lack of involvement—in an Incan civil war, with the victorious leader executing many Canari who were believed to have supported the opposing side.

Once the Spanish arrived, the Canari shifted allegiance, aiding the conquistadors significantly during the siege of Cuzco in 1536–37. However, this alliance brought them no favor, as Spanish records show that by the late 1500s, the Canari received no special treatment compared to any other tribe.

The Canari's origins are not tied to the Incas, and their exact beginnings remain uncertain. According to their myth, their ancestors emerged from a lagoon. Their mythology also includes a flood tale in which only two brothers survived, later finding a pair of parrots that provided them with food and drink. Eventually, one of the parrots was captured and transformed into a beautiful woman, who became the ancestress of the Canari people.

5. Clovis Culture

The Clovis people, named after the town in New Mexico where evidence of their culture was first uncovered, were once believed to be the ancestors of all Native American groups. This theory was supported by genetic evidence found in the remains of a small boy discovered in Montana, the only human skeleton directly linked to the Clovis culture. Around 80 percent of today's Native American population can trace their ancestry to this individual.

Much of the proof of the Clovis people's presence in North America comes from artifacts known as ‘Clovis points’—fluted stone projectiles made from materials like jasper and obsidian. These tools, dating back around 13,500 years, have not yet been definitively linked to specific uses, such as spears or darts.

The 'Clovis first' hypothesis has lost support among many scientists, as new evidence reveals multiple cultures predating the Clovis by centuries. Despite this, it’s important to note that no genetic data suggests these earlier peoples were genetically distinct from the Clovis. Rather, it indicates there was at least one migration before the Clovis migration. Moreover, even though the projectile points found at earlier sites differ from those of the Clovis, this could simply reflect an evolution in technology.

4. Taino Civilization

Upon Columbus's arrival in 1492, the Taino people were his first encounter. At the time, they were the predominant civilization in various Central American regions, including Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola. It’s estimated that the Taino population on Hispaniola could have been as large as three million, though a more likely figure is around one million. Some estimates suggest that the Taino civilization as a whole numbered between three and six million.

The Taino people never developed their own written language, yet they were highly skilled in various fields. In fact, several Taino words made their way into the global lexicon, such as ‘barbecue,’ ‘hammock,’ ‘tobacco,’ and ‘cannibal.’

The Taino's pottery was beautifully crafted, but their extreme generosity ultimately led to their downfall. Columbus wrote about them: “They will give all that they do possess for anything that is given to them, exchanging things even for bits of broken crockery. [ . . .] They should be good servants.”

Regrettably, the fate of the Taino people was tragically common for many Native American groups. Within 50 years of Columbus’s arrival, little of their civilization remained, with many perishing from disease, starvation, and enslavement. Some estimates place their population loss at as much as 85 percent. Many Taino women were forced to marry their conquistador captors, giving rise to a mestizo population that some claim as their ancestors today.

3. Totonac Civilization

The Totonac were the first natives to meet Cortes upon his arrival in Mexico. They had recently been subjugated by the Aztec Empire. For generations, they had fought against the Aztecs, but eventually, they were defeated and grew weary of the constant conflict.

Much like other tribes, the Totonac viewed Cortes as a potential liberator from Aztec oppression and therefore allied themselves with the Spanish. Additionally, the Totonac were among the earliest to convert to Christianity, as Cortes, disturbed by the practice of human sacrifice, sought to convert the natives as quickly as possible.

While the Totonac were spared from direct warfare with the Spanish, they succumbed to the diseases brought by the Europeans, which devastated their population. Nevertheless, many survived, and their descendants still live in the towns of Puebla and Veracruz in southern Mexico. Some scholars believe the Totonac were responsible for the construction of some of Mesoamerica's greatest cities, such as Teotihuacan and El Tajin.

2. Tarascan State

Archaeological findings suggest that in the 13th century, a large group of people migrated into what is now Michoacan, a state in western Mexico. Fiercely warrior-like, they soon overtook the region's inhabitants, establishing a sophisticated system of governance: a collection of city-states united under a central king. Their military prowess allowed them to expand their territory and even defeat the Aztecs in battles toward the end of the 15th century.

After Hernan Cortes captured the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521, the Spanish, having heard rumors of untapped gold and silver deposits in the Tarascan region, set their sights on it. For nearly ten years, the Tarascan people, led by Tangaxuan II, paid tribute to the Spanish and coexisted relatively peacefully with their conquerors.

In 1530, however, everything changed when the Tarascan leader was assassinated. The following decades were marked by conflict, slavery, and disease, leaving the population in turmoil. It wasn’t until Spanish bishop Vasco de Quiroga intervened that some of the problems were addressed, ultimately leading to the Tarascan people's cooperation with the Spanish.

The Tarascan people had an interesting cultural characteristic: they were largely independent and did not engage in much trade with neighboring regions. There is little evidence of exchanges between the Tarascan state and the Aztec Empire. This may be explained by the vast territory and abundant resources controlled by the Tarascans, making trade unnecessary for them.

Although their culture shared many similarities with other Mesoamerican civilizations, the Mixtec people never developed a writing system or a complex calendar. However, their expertise in ceramic pottery stood out, with the Spanish even documenting their exceptional craftsmanship.

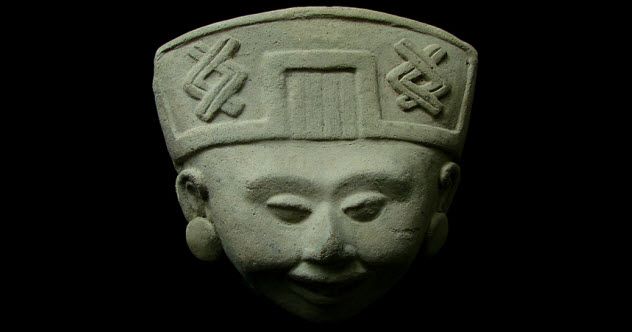

1. Mixtec Civilization

Thanks to the fortunate survival of numerous codices, the Mixtec civilization is one of the most well-understood pre-Columbian cultures. Their political system was similar to ancient Greece, as they did not have a central capital like many other civilizations did.

The Mixtec civilization was made up of various city-states, each ruled by its own king. If the Mixtec had a capital, it would likely be Tilantongo, a site known for its vast ruins. Their cities were structured with a clear social hierarchy, where kingship passed down through family lines, and the working and servant classes primarily served the elite.

The Mixtec culture, still present in the Oaxaca Valley of southern Mexico, began to take shape around AD 600. However, their status as an independent nation came to an end during the late 15th and 16th centuries, either through conquest by the Aztecs or the Spanish.

The Mixtec were celebrated for their artistic skill by neighboring tribes and were also known for their trading, particularly their expertise in metalworking and crafting turquoise jewelry. Their writing system was predominantly pictographic, with the Vienna Codex being one of the most notable, featuring painted images on deerskin.

One of the most influential rulers of the Mixtec civilization was Eight Deer Jaguar Claw, who expanded their territory during the 11th century. According to the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, he conquered several cities but was ultimately sacrificed for attempting to establish a monarchy-like system of governance within the civilization.