For centuries, humanity has pursued the same timeless desires: the accumulation of wealth, the discovery of miraculous remedies to heal the world's suffering and diseases, and the ability to erase haunting memories. These aspirations have inspired countless tales and myths about extraordinary, magical substances capable of turning these dreams into reality.

10. Lyngurium

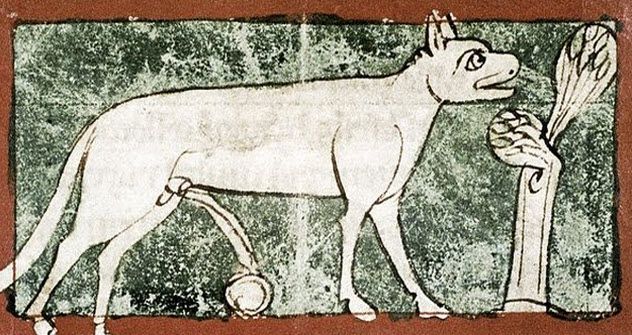

The earliest reference to a gemstone known as lyngurium originates from the writings of Theophrastus of Eresus. Theophrastus, often regarded as the pioneer of lapidary studies for his exploration of gemstone properties and theories on their formation, described lyngurium as nothing more than hardened lynx urine.

Theophrastus penned his works in the third or fourth century BC, and his ideas were frequently referenced up until the Renaissance. Numerous medieval lapidaries include mentions of the lynx stone, even though no one has ever actually encountered one. Translations of ancient texts depict the stone as solidified urine, asserting that the urine of a wild lynx yields a superior stone compared to that of a domesticated one. Male lynxes produce more potent stones than females, and locating such a stone is challenging, as lynxes are said to bury it.

The stone is described as a translucent yellow with captivating, almost magnetic qualities. However, lyngurium is said to affect nonmetallic objects as well, particularly plant-based materials like straw and leaves.

Rumors also circulated about its healing abilities. It was believed that placing the stone in a liquid and consuming the mixture could dissolve bladder stones and treat jaundice. Some even claimed that merely gazing at the stone could bring about a cure.

Subsequent writings attributed even more fantastical powers to the stone, with one source suggesting it could completely alter a person’s gender. By the time medieval texts mentioned the stone, it was said to safeguard homes and individuals from harm, particularly effective against stomach and digestive ailments.

Those lucky enough to discover the stone were advised to soak it in warm cow’s or sheep’s milk for 15 days. However, attempting to use it for conditions other than its renowned curative properties would result in the person’s skull fracturing.

Lyngurium is classified among Theophrastus’s “gendered stones,” with male stones described as significantly darker than female ones, a recurring theme in early gemology. While other ancient writers, such as Pliny, dismissed the existence of such a stone, their views were overshadowed by believers. Medieval authors expanded the stone’s lore, claiming that lynxes harbored a resentment toward humanity and concealed the precious gems in their throats to prevent humans from finding and utilizing them.

9. Azoth

Even experts writing about azoth struggle to define it precisely. The term originated with Paracelsus, who used it to describe an alchemical substance he believed to be a universal cure. It is sometimes associated with what we now recognize as mercury, though it also refers to a fundamental element or property inherent in all metals. Later interpretations of Paracelsus’s work suggest he may have assigned the name to an entirely different substance: his most famous invention, laudanum.

During the 1920s, Manly P. Hall published an extensive work titled The Secret Teachings of All Ages, in which he attempted to decipher the true nature of azoth. He proposed that azoth was an alchemical element existing alongside the fundamental trio of salt, mercury, and sulfur. (However, these were not ordinary minerals but rather complex substances composed of all three, with one dominant aspect in each mixture.)

Azoth was considered a genuine essence of life, yet its true identity remained elusive. Some theories posited it as an invisible force, while others speculated it could be electricity, a magnetic substance, or even an eternal flame.

Azoth was also associated with the sphere of Schamayim, which represents the manifestation of the Word of God. This Word split into fire, giving rise to the Sun, and water, forming the Moon. The remainder was azoth, a universal mercury believed to be the source of all life.

8. Ambrosia and Nectar

Ambrosia is widely recognized as the sustenance of the Greek gods, granting them eternal life. However, numerous legends and myths surround its extraordinary powers. When consumed by deities, this sacred food transforms into ichor, a divine fluid that flows through their veins, serving as the very essence of their immortality. For divine offspring like Apollo, ambrosia had the remarkable ability to instantly accelerate their growth to adulthood.

On rare occasions, ambrosia found its way into the mortal world. In Homer’s Iliad, Patroclus wore Achilles’ armor and led a contingent of warriors against Troy. After being rendered unconscious by Apollo, he was slain by Hector and Euphorbus.

Following his death, a fierce battle ensued to retrieve his body for a proper burial. The nymph Thetis intervened, using ambrosia to preserve Patroclus’s corpse, preventing decay until Achilles could honor his friend with a fitting funeral. When bestowed upon a living mortal, ambrosia could bestow unparalleled beauty, as seen when Athena allowed Penelope to partake in the divine substance.

The true nature of ambrosia remains a mystery. While it is often described as a form of fermented honey, it is also associated with grape wine. Some theories propose that it might actually be a type of mushroom known as fly agaric (Amanita muscaria).

The satyrs and centaurs, among the most notorious figures in Greek mythology, were believed to host an annual celebration known as “the Ambrosia.” Artistic representations of this feast often depict what appear to be magical mushrooms alongside the merrymakers.

7. Orichalcum

Enthusiasts of role-playing games might recognize orichalcum from the Elder Scrolls franchise, where it is linked to Orcish blacksmiths and the exceptional armor they craft from this metal. However, the concept of this enigmatic material predates Elder Scrolls by centuries. The term was first used by Homer and later by Plato to describe a mysterious metal allegedly forged by the Atlanteans.

Orichalcum was a cornerstone of Atlantis’s prosperity, and Plato claimed that only gold surpassed it in value. Translating “orichalcum” to mean something akin to “mountain brass,” Plato provided little detail about its composition, other than emphasizing its role in Atlantis’s wealth. He described it as having a fiery hue, while other ancient texts portrayed it as a golden metal linked to gods like Aphrodite.

An ancient text, De mirabilibus auscultationibus, claims that orichalcum was created by blending copper with a unique type of earth found exclusively near the Black Sea. By the Roman era, the metal was referred to as aurichalcum and was often associated with gold. Pliny noted that by his time, the metal was no longer mined, as its sources had been exhausted.

Speculations about the real-world counterpart of orichalcum range from phosphoric bronze to various copper alloys. The ancient Greeks attributed its invention to Cadmus, the founder of Thebes. While its existence seemed as mythical as Atlantis itself, in 2015, divers discovered orichalcum ingots in a 2,600-year-old shipwreck off the coast of Sicily.

Analysis of the 39 ingots revealed they consisted of 75–80 percent copper, 15–20 percent zinc, and trace amounts of iron, lead, and nickel. Archaeologists believe the metal was primarily used for decorative purposes. This discovery validates part of Plato’s narrative: orichalcum and the skilled artisans of the sixth century BC brought immense wealth to Gela, if not Atlantis.

6. Unspoken Water

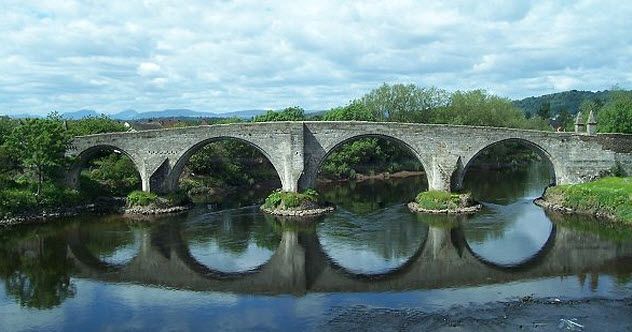

According to Scottish folklore, unspoken water is a potent cure for various ailments. It must be gathered in complete silence at either dawn or dusk, sourced from water flowing beneath a bridge that serves both the living and the dead. Once brought to the home of the person requiring healing, there are differing beliefs about its proper use.

Some traditions dictate that the individual must drink the water three times before any words are spoken in the house. In other practices, the water is sprinkled around the home to invoke its cleansing properties, and occasionally, the container used to collect the water is also tossed over the house. At times, the water is incorporated into more elaborate rituals, such as boiling eggs for breakfast, as mentioned in certain texts.

The water’s power was thought to derive not only from its source but also from the silence maintained by the person who collected it.

5. The Moon Rabbit’s Elixir of Life

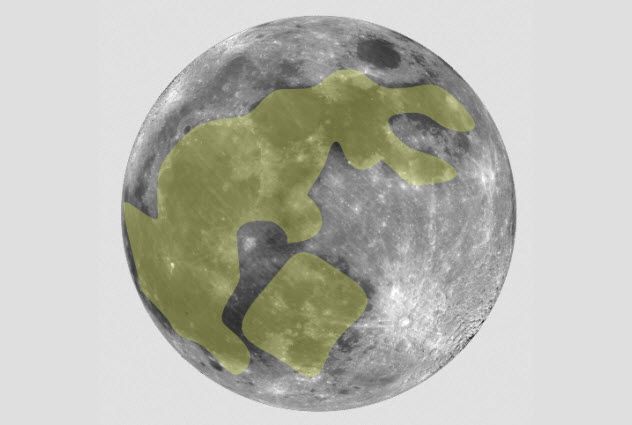

Mythology and folklore recount tales of various creatures believed to inhabit the Moon, including China’s Moon Rabbit. According to legend, when the Buddha disguised himself as a sage and asked animals for food, the rabbit was the only one without anything to offer.

Rather than presenting nothing, the rabbit leaped into a fire, sacrificing itself as a meal. Grateful for this selfless act, the Buddha placed the rabbit on the Moon. There, it is said to spend eternity crafting a mystical potion known as the elixir of life, blending its ingredients atop a toad’s head.

An alternate tale explains that the rabbit was sent to the Moon to keep Chang’e company. Chang’e, the wife of the legendary archer Hou Yi, consumed a magical elixir given to her husband as a reward for shooting down nine of the ten suns that once scorched the Earth. As punishment, she was banished to the Moon.

Once the Moon Rabbit arrived, its mission was to brew the elixir of life for both the immortals and Chang’e. Known also as the Jade Rabbit or Gold Rabbit, it is said to use its mortar, pestle, and mystical components not only to create the elixir but also to craft a pill that could one day allow Chang’e to return to Earth.

4. The Net

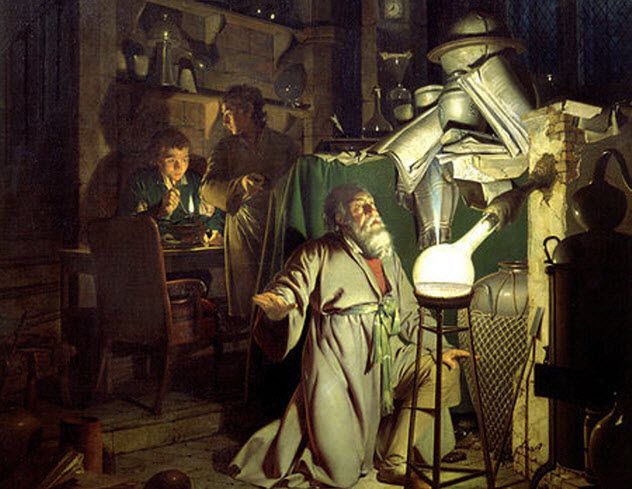

Isaac Newton, renowned for his scientific achievements, was also a secretive alchemist whose work remained hidden during his lifetime. Recently, scholars have revisited his alchemical notebooks, decoding and reproducing some of his experiments.

Like countless alchemists before him, Newton sought the philosopher’s stone. He based his research on the findings of earlier generations and concluded that a key component was a substance he called “the net.” This peculiar name stemmed from Newton’s belief that ancient Greek myths were encoded messages, similar to the cryptic language used by alchemists of his time.

One myth describes how Aphrodite (Venus) was caught in an affair with Ares (Mars) by her husband Hephaestus (Vulcan), who crafted an invisible net to trap them. Newton interpreted this tale as a metaphorical recipe for creating a foundational element of the philosopher’s stone, which he referred to as the net.

The names of gods and planets often symbolized metals in alchemical texts. Newton combined this mythological framework with the work of George Starkey, an American alchemist who developed an alloy of antimony and copper. Modern researchers have successfully recreated this alloy.

While the substance did not ultimately contribute to the creation of the philosopher’s stone (as far as we know), its unique properties were compelling. The alloy’s surface displayed crystalline patterns, which alchemists interpreted as evidence that they were nearing their goal.

3. The Water of Lethe

In Greek mythology, the underworld is home to five rivers: Styx, Kokytos, Pyriphlegethon (Phlegethon), Acheron, and Lethe. Lethe, introduced in later myths, became known as the river of forgetfulness. Unlike Styx, Kokytos, and Acheron, which had connections to the living world, Lethe existed solely in the underworld, its waters embodying complete oblivion.

Plato was the first to describe the properties of Lethe’s waters, attributing to them the power to erase all memories of those who drank from it. However, there was a condition: while all souls drank from Lethe upon death, its effects did not apply to those who had committed crimes in life. These individuals remained haunted by the memories of their misdeeds.

Plato also proposed that Lethe facilitates the rebirth of souls. After death, drinking from the river erases all memories, allowing individuals to begin anew in their next life. This process applies to almost everyone, with the exception of Aithalides, the son of Hermes, who was cursed with an unyielding memory that persisted across the realms of the living, the dead, and future incarnations.

The waters of Lethe were occasionally used by the living, but only in specific situations. Those seeking wisdom from the oracle of Trophonios at Lebadeia were directed to drink from a nearby spring, which was connected to Lethe. This water was believed to clear the mind of all distractions, preparing the seeker for the oracle’s guidance.

Afterward, drinking from a second spring enabled the supplicant to retain the oracle’s instructions. Similarly, those who ventured into the underworld and drank from the underground Lake Mnemosyne could remember their experiences there.

2. Dragon’s Teeth

Cadmus, known for creating orichalcum, is also linked to another legendary substance: dragon’s teeth.

Cadmus (also called Kadmos) received divine guidance to follow a specific cow until it rested, marking the spot where he was to establish a new city. This city would become Thebes. However, he faced a challenge. To honor the gods (sometimes Athena, sometimes Earth) with a sacrifice, he needed sacred water.

The water was protected by a creature described as a dragon, though it resembled a giant snake more than the dragons we imagine today. After slaying the beast, Cadmus was told to extract its teeth and plant them. From these teeth sprang a group of fully armed warriors, who, in one version of the tale, immediately began fighting each other until only five survived. These five, known as the Sown Men or Spartoi, founded the five noble houses of Thebes.

The concept of dragon’s teeth possessing magical properties that sprout warriors reappears in the tale of Jason and the Golden Fleece. When Jason arrives in Kolkhis, the king presents him with some of the teeth from the dragon Cadmus had slain.

Jason was commanded to plant the teeth and battle the warriors that emerged. In some accounts, he throws stones into their midst, causing them to attack each other. In other versions, Medea provides him with a protective ointment, rendering him invulnerable. Occasionally, the dragon’s teeth produce an entire army of warriors.

1. Toadstones

The toadstone was believed to be a literal stone extracted from a toad’s head. This legend likely originated in the second century with Kyranides, who claimed that toads secreted a substance that solidified into a stone stored within their heads.

Toadstones were harvested in various ways—ranging from the benign (waiting for the toad to expel the stone and snatching it before it could be swallowed again) to the gruesome (placing the toad in a pot of flesh-devouring ants until only the stone remained). The concept of the toadstone appeared in gemstone literature and Early Modern European art, where Agostino Scilla observed that these mythical stones closely resembled fossilized fish teeth.

This discovery undermined the toadstone’s mystique, as its supposed magical properties were believed to stem from the toad itself. The stone, formed from secretions considered toxic, was thought to neutralize poison when touched to the skin, offering remedies for snake bites, insect stings, and even humoral imbalances believed to cause illnesses like fevers and tuberculosis.

While most accounts claimed the stone merely needed skin contact to work, some believed ingesting it could cure stomach and digestive issues. After being excreted, the stone could be set into jewelry for ongoing protection. It was also valued as a safeguard for new mothers and infants, believed to deter fairies intent on stealing the baby.

Toadstones were highly prized and even listed among the royal treasures in historical inventories.