For centuries, humanity has been entranced by ivory. This smooth, off-white material is mostly sourced from elephant tusks, though other animals like mammoths, walruses, whales, hippos, and warthogs have also contributed to the ivory trade.

Early hunter-gatherers utilized ivory not just for tools but also for their most revered objects. Over time, many civilizations have transformed ivory into both ornamental and functional creations.

The allure of this prized material is so strong that it has led to the near-extinction of many ivory-bearing species. Today, the world faces the challenge of finding a substitute for this exquisite yet unsustainable resource.

10. The Ivory Rope-Making Tool

In August 2015, archaeologists uncovered a 40,000-year-old ivory tool used for rope-making in a cave in southwestern Germany. Initially thought to be a flute or shaft straightener, this tool, made from mammoth tusk, is 20 centimeters (8 inches) long and has four holes, each etched with deep spiral grooves.

This was not just an ornament. It was an advanced technological tool from the Stone Age. The spiral markings guided plant fibers as they were twisted into rope. Hohle Fels Cave, the site of the discovery, has produced an invaluable collection of well-preserved Paleolithic tools and art.

Rope was crucial for the survival of mobile hunter-gatherer groups. For years, the Paleolithic rope-making method remained a mystery. Rope and twine would quickly degrade, leaving almost no trace in the archaeological record, except in rare instances when they were preserved in fired clay. German researchers have now demonstrated how individual plant fibers were threaded through the holes to create durable rope strands.

9. Illyrian Ivory Tablets

In 1979, an Albanian archaeologist uncovered five 1,800-year-old ivory tablets during digs at Durres. Fatos Tartari discovered the wax-coated tablets inside a glass urn, alongside two styluses, an ebony comb, and black liquid.

The urn was found in the tomb of an aristocratic woman. The mysterious liquid preserved the ivory tablets, as wax typically deteriorates and separates as soon as it loses moisture.

A collaborative team of German and Albanian scientists has recently decoded the inscriptions, revealing insights into the Roman colony of Dyrrachium in the second century AD. The records highlight that women played a prominent role in ancient Illyrian society.

The inscriptions suggest that the woman interred in the tomb was a moneylender. One entry notes that she was owed a debt of 20,000 denarii—ten times the annual pay of a Roman soldier. Ancient accounts reveal that Illyrian women fought alongside men and wielded political influence.

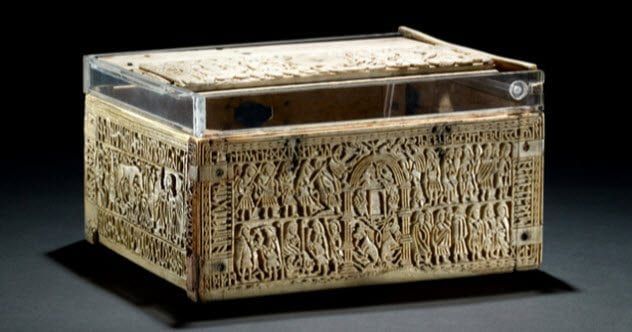

8. The Franks Casket

The Franks Casket is an Anglo-Saxon whale bone box, embodying a fascinating blend of Christian, Jewish, and Germanic influences. Dating back to the early eighth century, this ivory artifact depicts scenes from the Adoration of the Magi alongside the Germanic myth of Weland’s Exile. The lid features the Germanic hero Egil, while the underside shows the Roman conquest of Jerusalem in AD 70. Runic, Old English, and Latin inscriptions are carved on the box.

Measuring 23 centimeters (9 inches) long, 19 centimeters (7 inches) wide, and 11 centimeters (4 inches) high, this ivory box likely contained sacred texts. Some suggest it might have served as a reliquary for the cult of St. Julian in Brioude.

A 1291 account mentions the Lord of Mercoeur visiting Brioude and “devoutly kissing an ivory box filled with relics.” In the early 19th century, a family in Auzon, France, owned the casket and repurposed it as a sewing box.

7. 40,000-Year-Old Animal Figurine

In 2013, archaeologists successfully reattached the head to a 40,000-year-old ivory lion sculpture. Found in Vogelherd Cave in 1931, the lion’s body was later reunited with its head, which had been discovered during an excavation at the same site between 2005 and 2012.

Initially thought to be a relief, the discovery of the head confirmed it as a detailed, three-dimensional representation of the ancient predator.

Vogelherd Cave is situated in Germany’s Lone Valley, in the southwest. Spanning over 170 square meters (1,830 ft), the cave has produced more than two dozen figurines dating back to the early days of Homo sapiens in Europe.

In addition to lions, ivory figures depicting mammoths, camels, and horses have also been found. These pieces are regarded as some of the most remarkable Ice Age artworks, marking significant milestones in humanity’s developing cultural innovation. Bone deposits suggest the cave was used for game processing and butchering over millennia.

6. Greenland Walrus Ivory

Archaeologists believe that an ancient “gold rush” spurred the Viking settlement of Greenland. However, their quest wasn’t for precious metals but for walrus tusks.

In the 11th century, Europe’s fascination with ivory surged. Driven by a demand for luxury items, the Vikings quickly capitalized on Europe’s growing thirst for tusks. Walrus ivory was crafted into jewelry, religious icons, and extravagant goods for the elite.

Between the 12th and 14th centuries, the Viking economy shifted focus from bulk goods—such as wool, fish, and timber—to luxury items like ivory. The long-standing mystery of why the Vikings chose to settle in Greenland, a land too harsh for farming, may have finally been resolved.

Medieval Iceland also had a walrus population, but it was likely insufficient to satisfy Europe’s growing demand for ivory. Greenland, however, could meet this need. Researchers are now studying isotopes in walrus ivory to trace its origins.

5. Venus Of Brassempouy

In 1892, archaeologists uncovered a mysterious ivory figurine during excavations at Brassempouy in southwestern France. Dating back to approximately 23,000 BC, the “Venus of Brassempouy” features the earliest-known detailed depiction of a human face.

The figurine shows eyes, brows, a forehead, and a nose, but it lacks a mouth. A vertical crack runs through her face, likely a flaw in the ivory. It’s unclear whether her hair is braided or covered by a headdress. Only the head and neck of the Venus were found in Grotte du Pape (“Pope’s Cave”).

The Venus of Brassempouy is one of the finest examples of Gravettian art. It was created around the same time as other well-known female figurines, like the Venus of Dolni Vestonice in the Czech Republic and the Venus of Savignano in Italy. The tradition of ancient Venus figurines extends as far east as the shores of Siberia’s Lake Baikal.

4. Dorset Polar Bear Effigies

The Dorset were a mysterious group of hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Canadian Arctic from 500 BC to AD 1000. Named after Cape Dorset, where their artifacts were first found, the Dorset were renowned ivory carvers.

The polar bear was their most common subject. Hundreds of ivory carvings of Dorset bears have been discovered in Greenland and Northern Canada. Some believe the bears are shown in poses typical of seal hunters, while others argue that certain carvings, like the “flying bear” effigies, may reflect the Dorset’s spiritual beliefs.

The Dorset vanished soon after the Inuit began to encroach on their territory, leaving behind only their mysterious artifacts. Inuit legend describes the Dorset, or “Tuniit,” as giants who could effortlessly crush a walrus’ neck and carry it home.

Despite their giant stature, the Tuniit were gentle giants who lived isolated lives. Artifacts are far more common than tools like harpoon heads and knives, and even the Dorset's functional items are often highly decorative.

3. Lewis Chessmen

In 1831, 78 intriguing ivory chess pieces were uncovered on the beach of Lewis in the Hebrides. Alongside the buckle of the bag they were once stored in, the Lewis chessmen have become one of Scotland’s most prized archaeological discoveries and are among the most iconic chess pieces in history. Weighing 1.4 kilograms (3 lbs) in total, the find consists of nearly four complete sets, missing only one knight, four rooks, and 44 pawns.

While the pawns are simply octagonal in shape, the other pieces are far from ordinary. The queens are captured in expressions of shock or sorrow, the kings stand resolutely in an almost comical stoicism, the rooks appear fierce, biting their shields in battle, the knights seem out of place atop their tiny ponies, and the bishops have eyes that bulge out from their round faces.

Experts suggest that the pieces made from walrus tusks and whale teeth were crafted in Norway around the late 12th century. However, the true identity of the carver of the Lewis chessmen and how they ended up in the Hebrides remains a mystery.

2. Venus In Furs

In 1957, archaeologists uncovered intriguing female figurines carved from mammoth tusk in Buret, Siberia. Named “Venus in Furs,” these mysterious ivory objects were initially thought to represent Venus, but closer inspection revealed that some were depictions of men and others of children.

Experts now believe that the figurines represent real individuals from 20,000 years ago. These 'Venus in Furs' figurines, showcasing clothing suited for the harsh Siberian winter, are the earliest known depictions of sewn garments. Detailed analysis has revealed various hairstyles, shoes, and accessories worn by the figures.

The 'Venus in Furs' figurines bear a striking resemblance to those discovered in Mal’ta, located just 25 kilometers (15 miles) away. To date, 40 mammoth tusk figurines have been unearthed at both locations near Lake Baikal.

Only slightly more than half of these figurines have undergone microscopic examination. Continued research could bring forth new and surprising insights, as several details such as bracelets, hats, shoes, and bags have been obscured by time and are not visible to the naked eye.

1. Athena Parthenos

In 438 BC, the Athenian leader Pericles tasked the renowned sculptor Pheidias with creating the Athena Parthenos in tribute to the city’s patron goddess. Standing at an impressive 11.5 meters (37.7 ft), the statue was truly monumental.

This masterpiece was crafted using the chryselephantine technique—featuring 1,140 kilograms (2,500 lb) of gold and pure white ivory for the goddess’ figure. The statue was further embellished with glass, copper, silver, and precious gems. Historians estimate its cost at around 5,000 talents, a sum greater than the construction cost of the Parthenon itself, where the statue was displayed.

For over a thousand years, the Athena Parthenos stood as Athens’ iconic symbol. However, by Late Antiquity, it disappeared from historical records. Some theories suggest that it was transported to Constantinople, where it was likely destroyed.

Despite the original’s disappearance, replicas survive. The most famous of these is the Varvakeion statuette from the second century AD. Along with descriptions by ancient historians like Plutarch and Pausanias, scholars have a clear idea of what the original statue looked like.