For millennia, the Chinese have carefully chronicled their nation's vast and compelling history. A broad range of details has been documented and safeguarded. Thanks to the dedication of these historians, China boasts an impressively well-preserved historical record.

However, not every detail is clear in the country’s historical records. Some of China’s most fascinating figures remain cloaked in mystery, victims of assassinations and disappearances that are unlikely to ever be unraveled.

10. The Execution Of Kawashima Yoshiko

Kawashima Yoshiko, a Chinese princess, served as a cross-dressing spy for the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Born into a Manchu family with the name Aisin Gioro Xianyu, she was adopted in 1915 by a Japanese friend of her father, who renamed her Kawashima Yoshiko after the fall of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty.

Kawashima’s time in Japan was marked by hardship. It’s reported that her stepfather sexually assaulted her, and she faced discrimination from her classmates due to her Chinese heritage. Eventually, she returned to China, disguised herself as a man, and became a spy. The princess aligned herself with imperialist Japan, combating Chinese guerrilla forces and seducing officials to steal military secrets.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Kawashima was arrested by the Chinese and executed by a gunshot to the back of her head for treason. A photo of her lifeless body appeared in Life magazine, though Beijing newspapers claimed the princess had used a body double and managed to escape.

Years after Kawashima’s presumed death, a team of Chinese historians conducted an investigation. They examined the testimonies of two women from Northeast China, who claimed that their elderly neighbor, Granny Fang, was actually Kawashima Yoshiko. The historians were convinced the women were correct and believed that their father, who once worked with Kawashima, helped her flee.

9. The Disappearance Of Xu Fu

Qin Shi Huang, the ancient Chinese emperor famous for the tomb housing his army of terra-cotta soldiers, was obsessed with the idea of immortality. Terrified of death, he sought out magicians and charlatans who claimed to possess the secret to prolonging his life. One of these figures was Xu Fu, who convinced the emperor that he knew the location of the fabled elixir of life.

Xu Fu claimed that the elixir could be found on a series of islands in the Yellow Sea, guarded by immortal beings. In 219 BC, the emperor dispatched Xu to find the elixir, accompanied by 3,000 virgins—both boys and girls—whose purity, he said, was key to accessing the elixir.

As expected, Xu Fu returned to China empty-handed. He told the emperor that he was thwarted by sea monsters preventing him from reaching the islands. The emperor, not discouraged, provided Xu with archers and sent him off once more. This time, Xu Fu never returned. Official history remains silent on his fate, but Japanese legends suggest that Xu landed in Japan, where he became greatly revered, even worshipped as a god by some.

8. The Contest To Cut Down 100 People

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japanese newspapers covered an odd story about Lieutenants Mukai Toshiaki and Noda Tsuyoshi, who were participating in the invasion of China. In the winter of 1937, the two soldiers engaged in a brutal contest where each contestant had to kill Chinese people using a sword. The first to slay 100 individuals would be declared the winner.

On December 12, the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shimbun reported that the contest ended in a draw. Both Mukai and Noda had surpassed 100 kills, so they decided to set a new goal, this time with a target of 150 kills. While the soldiers appeared to view the contest as a game, the Chinese were naturally outraged by the mass slaughter of their people being treated as entertainment. After the war, Mukai and Noda were sentenced to death at the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal.

Some critics, particularly nationalist groups that deny the scale of Japanese wartime atrocities, argue that the contest either never occurred or was greatly exaggerated. Katsuichi Honda, a journalist who angered many nationalists with his honest postwar reporting on the Nanjing Massacre, believes the latter. He suggests that similar killing contests took place during the war, but the victims of Mukai and Noda were prisoners of war, who, despite the newspaper reports, were not killed in direct combat.

7. The Disappearance Of Peng Jiamu

Lop Nur, a desolate and arid lakebed in China’s Xinjiang province, is notorious for its extreme weather conditions and shifting sand dunes. It’s a perilous and isolated location, making it an ideal place for Peng Jiamu to explore. Peng, a biologist from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, took part in numerous scientific expeditions to Lop Nur and other areas of Xinjiang.

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) temporarily hindered Peng and his team’s progress in their explorations, but by the summer of 1980, Peng was able to launch another expedition to Lop Nur. On June 17, he left the camp alone in search of water, never to be seen again.

A large-scale search effort, involving both military personnel on foot and in the air, failed to locate any sign of Peng. It’s believed that he may have succumbed to the desert’s harsh conditions, yet repeated searches over the years have failed to recover his body. Intriguingly, there have been rumors suggesting that Peng left China for the United States. In September 1980, the son of Deng Xiaoping allegedly saw the missing scientist in a restaurant in Washington.

6. The Murder Of Shen Dingyi

Although born into a wealthy family, Shen Dingyi was deeply concerned with issues of economic inequality and the prevailing social structure. In 1907, he joined the Revolutionary Alliance, a secret Chinese society based in Tokyo, with the goal of overthrowing the Qing dynasty. In the early 1920s, Shen became a communist and returned to his village in Yaqian, where he advocated for reforms to benefit the local peasantry.

On August 28, 1928, after visiting a mountain resort, Shen boarded a bus to return home. When the bus reached his stop, he stood up to head to the front. Just as he was about to show the driver his ticket, two passengers suddenly pulled out guns and shot him multiple times. The assassins then fled the scene, firing at anyone who attempted to pursue them.

Shen Dingyi had many enemies, which made him a prime target for assassination. His reforms were opposed by merchants and landlords, and while the Communist Party despised him, so did the Guomindang. Either of these factions could have orchestrated his murder. Numerous suspects were detained and interrogated during the investigation, but no one was ever formally charged with Shen’s death.

5. The Stick Case

On May 30, 1615, a peasant named Zhang Chai broke into the Forbidden City wielding a stick and attacked a eunuch guard. At the time, the Forbidden City housed China’s royal family. Zhang attempted to enter the palace where Emperor Wanli’s son resided, but a group of eunuchs caught him before he could reach his goal.

Initially, the authorities thought Zhang was simply a madman acting alone. However, after repeated questioning and torture, Zhang claimed that a conspiracy of eunuchs had orchestrated the attack. According to his story, the eunuchs had shown him how to infiltrate the Forbidden City, where he was instructed to assassinate the emperor’s son, Zhu Changluo. Zhang specifically named eunuchs Pang Bao and Liu Cheng as the ones who recruited and armed him.

Emperor Wanli ordered a trial for Liu, Pang, and Zhang. Zhang was executed, while Liu and Pang were tortured until they died from their injuries. As for Zhu Changluo, he dismissed the plot as the ramblings of a madman and did not believe there had been any real conspiracy to kill him. Interestingly, five years later, Zhu died under mysterious circumstances after ascending to the throne as Emperor Taichang.

4. The Mysterious Disappearance of Chu Anping

On June 1, 1957, a journalist by the name of Chu Anping delivered a controversial speech to a Communist Party committee entitled 'Comments Made to Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou.' At the time, China had been under Communist control since 1949, and Chu saw little difference from the rule of the former dynasties. He even compared Mao Tse-tung to an emperor.

Despite Mao’s recent launch of the Hundred Flowers Campaign, which encouraged open criticism of the party, Chu’s speech enraged the leader. As a result, Chu was dismissed from his position as the editor of The Guangming Daily, labeled as an anti-socialist right-winger, and essentially erased from the public sphere.

In August 1966, amid the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, Chu was forced to attend a struggle session. During this time, he attempted suicide by jumping into a river, but he survived. After returning home in September, Chu disappeared once more. It’s possible that he either attempted suicide again or was secretly killed by the Red Guards. Whatever the truth, Chu’s family was allowed to hold a symbolic funeral for him in May 2015.

3. The Mysterious Death of Emperor Jianwen

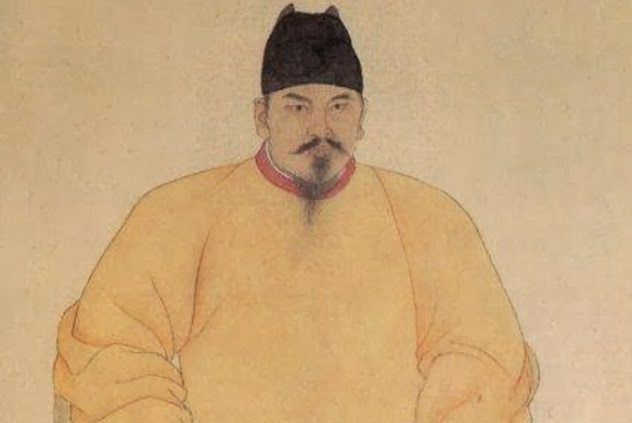

In July 1402, the Ming capital of Nanjing was attacked by the emperor’s uncle, Prince Zhu Di. Three years earlier, Zhu Di had accused his nephew, the young emperor Jianwen, of being swayed by the influence of his ministers. The prince’s rebellion, which he claimed was aimed at removing Jianwen’s ministers, was actually a power grab to take the throne for himself.

Amid the chaos of the invasion, Emperor Jianwen’s palace was set ablaze and reduced to ruins. Three charred bodies were recovered from the wreckage, which Zhu Di quickly identified as Jianwen, his empress, and their eldest son. With his nephew presumed dead, Zhu Di crowned himself Emperor Yongle. The new emperor then erased Jianwen’s records and purged his supporters, attempting to erase the history of his predecessor’s reign.

Despite Yongle’s assertions, rumors persisted that Jianwen had survived the palace fire. Some believed he managed to escape and lived out his life in seclusion as a monk in a remote part of China. In fact, it was even said that Jianwen had encountered one of his former court officials while fleeing to Yunnan province.

2. The Assassination of Song Jiaoren

Together with the prominent revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren helped establish the Guomindang, the nationalist political party that would govern China from 1928 to 1949. Following the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, Song was driven to push for democratic reforms. He aimed to limit the president’s authority, particularly that of Yuan Shikai, and aspired to become the prime minister and draft a new constitution.

On March 20, 1913, Song was shot by an assassin and succumbed to his injuries two days later. The assassin, Wu Shiying, an ex-soldier, had assistance from a man named Ying Guixing. After their arrest, a police search of their homes uncovered ties to Yuan Shikai and other high-ranking government officials. The situation turned even darker when Wu mysteriously died in jail, and Ying managed to escape, only to be killed by swordsmen on a train.

While the murder of Song Jiaoren was never solved, many historians speculate that Yuan Shikai played a role in the assassination. Yuan, who governed more like a dictator than a legitimate president, likely felt threatened by Song and the Guomindang, especially after they secured a majority in the provisional elections that spring. In December 1915, Yuan proclaimed himself emperor, but he passed away less than a year later in June 1916.

1. The Assassination of Lam Bun

1967 was a year of upheaval for the British colony of Hong Kong. Inspired by the Cultural Revolution sweeping across mainland China, coupled with discontent over colonial rule and harsh living conditions, leftist groups instigated a wave of riots that persisted from May through December. These disturbances were marked by bombings and violence, resulting in 51 deaths and more than 4,500 arrests.

The chaos from the riots caused many ordinary Hong Kong residents to rally behind the colonial government. The unresolved murder of Lam Bun, an outspoken anti-communist commentator at Commercial Radio Hong Kong, further fueled public sentiment against the leftists.

On August 24, Lam Bun and his cousin were ambushed by a group of leftists. Lam’s car was set on fire, and both he and his cousin perished in the flames. A guerrilla group claimed responsibility for the killings, but the perpetrators were never apprehended. The murders deeply shocked the public, and Lam Bun is now regarded as a symbol of free speech in Hong Kong.