Since the inception of laws, the death penalty has required an executioner to enforce it. While some of these individuals managed to separate their work from their personal lives, others took their grim duties to an unsettling extreme.

10. Simon Grandjean

On May 12, 1625, Simon Grandjean, the executioner of Dijon, along with his wife—who also assisted him in his grim profession—was assigned a task that should have been simple, though tragic. A dead infant had been discovered in the woods, wrapped in a blanket marked with a distinctive monogram. The mother, 21-year-old Helene Gillet, was quickly convicted of the crime. Despite her pleas of innocence and claims that the baby had been fathered by the family tutor, the sentence remained. Due to her family's high status—despite her father's disownment—she was granted the merciful execution of beheading.

While Helene and her mother sought justice through legal channels, a rumor began to spread that someone from the nearby Bernadine abbey had predicted that Helene would live to an old age, passing away from natural causes rather than by execution. Nevertheless, the law insisted she meet her fate.

One of the key duties of an executioner is to carry out the task without error, and sadly for Grandjean, this was not the case. His first strike only grazed her shoulder, and even more oddly, the second blow was deflected. The theory is that tying back a woman's hair should have ensured a clean cut, but the knot holding her hair back reportedly blocked the second strike.

By the time the second swing failed, the crowd had already been whipped into a frenzy, throwing whatever they could at the platform. Grandjean fled to a nearby chapel, while his wife pulled the condemned woman under the platform to shield her and attempted to finish the execution with a pair of shears. However, the crowd broke through and killed Madame Grandjean first, then dragged the executioner from his hiding place and tore him apart.

Helene's wounds, inflicted by the Grandjeans, were not fatal. This created a dilemma, as she was still considered guilty, but Dijon suddenly found itself without an executioner. Ultimately, she was pardoned by Henrietta Maria, the sister of Louis XIII, and was said to have spent the remainder of her life in a convent.

9. Artur Braun

In the early 20th century, Poland had difficulty finding a consistent executioner. A series of unfortunate events plagued the profession, including one man who took his life after claiming to be tormented by the ghosts of those he had executed. Another executioner sued the government after an especially harsh official ordered an execution without the customary black hood, allowing the condemned to retaliate and harm him.

In November of 1932, the search for a new executioner began. Out of 120 applicants, Artur Braun was selected. However, his career ended before it truly began. Elated by his success in landing the job, Braun and his friends went out to celebrate with drinks, but things soon spiraled out of control. Braun, it seems, wasn’t the most agreeable person when intoxicated.

Reports suggest that Braun and his friends ended their night at a bar, where things quickly escalated. Braun pulled out a gun and began shooting for reasons unknown, turning the evening into a full-fledged brawl. Broken bottles became weapons, innocent bystanders were assaulted, and Braun was dismissed from his position before he had a chance to execute anyone.

Though the fate of Braun after the shooting incident remains unclear, the Minister of Justice later stated that the next person appointed to the role of chief executioner would be someone who did not drink.

8. Dick Bauf

Born into a troubled family in Ireland, Dick Bauf was only 12 when his parents were arrested and convicted for a combination of breaking and entering and murder. In 17th century Ireland, child welfare was drastically different from today, and Bauf was spared execution on the condition that he carry out the sentence on his own parents. Initially hesitant, his parents gave their blessing, telling him they would rather be hanged by him than a stranger, and insisted that he do so to save his own life.

And so he did.

After the execution, Bauf struggled to find honest work and resorted to pickpocketing. Eventually, he joined a gang of thieves and took to scouting churches for valuables. As he traveled, Bauf decided that petty crime wasn’t enough for him and turned to highway robbery. He proved exceptionally skilled, and eventually, his victims sought help from the authorities. After capturing a group of men who were after the reward for his capture, Bauf burned them alive in a barn and fled to Scotland until the search for him subsided.

Once in Scotland, Bauf made the fateful mistake of becoming involved with a woman who was married to a man with a fierce sense of vengeance. He was quickly arrested and sent back to Ireland. Despite offering a large sum of money in exchange for clemency, Bauf was executed by hanging on May 15, 1702.

7. Cratwell

During the reign of Henry VIII, London’s executioner was a man known only as Mr. Cratwell. Although his job kept him busy, Cratwell still managed to attend the annual Bartholomew’s Fair, a major event held every August in honor of Saint Bartholomew. The fair was a lively affair, with market stalls, acrobats, musicians, and street performers. However, Cratwell couldn't resist the temptation of the stalls and was caught stealing from one of them.

At the time, Mr. Cratwell had a reputation for being a bit too tempted by the fair’s offerings, leading to his downfall. Despite his professional duties as an executioner, he let his greed get the better of him.

Around 20,000 spectators gathered to watch London’s executioner, who was described as 'a cunning butcher in quartering men,' meet his own fate at the gallows.

6. Capeluche

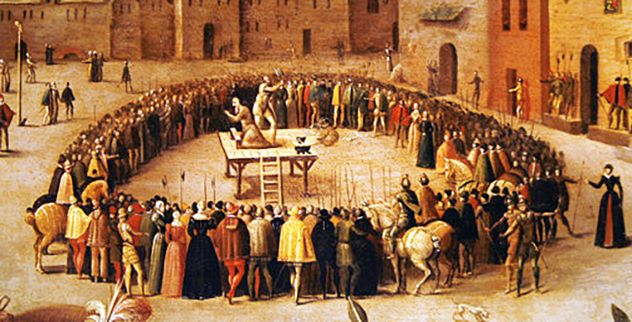

As the violence intensified, thousands of Parisians took to the streets in August, targeting the city's upper class. Leading the charge was the city’s executioner, Capeluche. In the chaos, homes were plundered and people were killed without mercy. When the Duke of Burgundy intervened, it seemed he struck a deal with Capeluche to spare some of the prisoners. But, predictably, the executioner reneged on the agreement, executing those he had promised to save.

The violence continued as Capeluche led the mob through Paris, ultimately betraying those he had sworn to protect, cementing his reputation as a ruthless figure in the turmoil of the time.

The Duke of Burgundy attempted to bluff his way out of the situation by claiming that an army of the feared Armagnacs was massing outside the city's gates. He convinced Capeluche to lead his men out of the city, but in the end, both Capeluche and two of his lieutenants were captured.

The next day, Capeluche met his fate as he was executed for his role in the uprising. However, a peculiar issue arose: with the executioner’s head awaiting the block, they needed someone to carry out the sentence. In a strange twist, Capeluche’s own valet volunteered. Reportedly, Capeluche spent his final moments meticulously instructing his stand-in on how to perform the task.

5. William Curry

Curry’s downfall was not marked by a dramatic or immediate death, but by a slow and painful descent into a life overshadowed by his struggles with alcohol, leaving behind a legacy of tragedy.

Curry never applied for the role of executioner. Instead, after being convicted of sheep theft and facing deportation to Australia, he found himself waiting for his sentence when the position of executioner became available. It was a way for him to remain in England, and he took it.

For the first 12 years of his tenure, Curry was still a prisoner, and he turned to alcohol to cope with his responsibilities as an executioner. His growing alcoholism severely impaired his work, earning him the infamous title of the 'bungling executioner,' a role no one wished to rely on. By 1821, he was so inebriated that, while preparing the noose for the hanging of a thief named William Brown, his irritation with the crowd's impatience led him to mock them, even daring them to try the noose themselves. A few months later, Curry was called upon to oversee the hanging of five men at once. Though they died, Curry's drunkenness caused him to lose track of his duties, and he stumbled, falling through the trapdoor.

Curry’s final act as executioner was the hanging of Ursula Lofthouse, convicted of poisoning her husband. Along with her, two thieves were also sentenced to hang that day. After Lofthouse's execution for killing her abusive spouse, Curry drunkenly wandered to a nearby pub and retired from his grim work. He spent the rest of his days working in a workhouse, another kind of confinement, unfit for anything else.

4. John Price

Even as a young man, John Price was infamous for his dishonesty. When he confessed to robbing a woman on the road to London, magistrates, believing such a confession was a sign of his innocence, decided to let him go. He eventually made his way to London, where he became involved in a series of unsavory activities that led to his arrest. Sent to Newgate Prison, he was eventually transferred to serve aboard a merchant ship, but his behavior became so troublesome that they keel-hauled him before dropping him off in Portsmouth.

After several returns to Newgate, Price managed to rise through the ranks. He married a young woman named Betty, who worked at Newgate running errands. With Betty's apparent influence and the impression that he was turning his life around, Price was appointed as the executioner for Middlesex.

Despite his new official position, Price didn't change much. He supplemented his income by selling the clothes of the men he executed. His only complaint about his new job was the responsibility that came with it: now he was accountable for the pain and death he caused.

Eventually, Price’s dark nature caught up with him. After brutally assaulting a pastry seller named Elizabeth White—beating her so severely that her eyes were forced from their sockets—he was stopped by two men who heard her screams. White succumbed to her injuries a few days later, and Price was arrested and sentenced to hang. He was left to dangle from the noose for the appropriate time before being gibbeted and displayed in Holloway.

This was in 1718, but Price’s story didn’t end there. His body was eventually buried at Ringcross in Holloway. In 1834, workers digging the roads unearthed a skeleton still wearing shackles. This skeleton was identified as Price's, and before being reburied, it was put on display at the Coach and Horses pub.

3. Paskah Rose and Jack Ketch

Jack Ketch became one of England's most notorious executioners, and his name became synonymous with the profession. Future executioners were often called 'Jack Ketch,' and his legacy even made its way into later Punch and Judy shows, forever cementing his place in history.

However, Ketch's career wasn't without its setbacks. Although details are scarce, it's known that he was imprisoned for 'affronting' a sheriff. While he was incarcerated, his assistant, Paskah Rose, was given the position of chief executioner in his stead.

Apparently, the role wasn't enough to keep Rose satisfied, either financially or in terms of workload. Along with his accomplice, Edward Smith, Rose resorted to burglary. On April 31, 1686, they were charged with breaking into the home of William Barnet, where they stole a coat and various clothes. They carried out the crime in broad daylight, so it was no surprise when a neighbor spotted them and gave chase. The duo managed to ditch some of the stolen items, but when arrested, police found that Rose had hidden some of the clothes in his pants, though his attempt to 'hide the loot' was far from successful.

Found guilty of the crimes they were accused of, Rose and Smith were both hanged at Tyburn on May 28 of the same year. Rose’s former mentor was released from prison specifically to carry out his execution, and Ketch himself passed away later that year.

2. John Ellis

John Ellis, born in 1875, had an unexpected journey from spinner to hairdresser and eventually to hangman. He served as an executioner from 1901 to 1924 but resigned amid rumors that the execution of Edith Thompson had left him so disturbed that he could no longer continue in his role.

By the time Edith Thompson faced the gallows for her involvement in her husband’s murder, Ellis had already executed some of the most notorious figures of the time, including Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen and Sir Roger Casement. Though he was well-versed in the grim realities of the job, Thompson's execution was a particularly gruesome affair. Prison records suggest that Thompson might not have been as complicit in the crime as the court had portrayed, as she repeatedly asked, 'Why did he do it?' By the time she was led to the gallows, she was near collapse, and guards had to support her as she was positioned for her execution. Critics would later claim that they had essentially hanged a woman who was barely conscious at the time.

After the hanging, it was revealed that her undergarments were soaked with blood, leading to rumors that she had been pregnant.

Though her pregnancy was never confirmed, Ellis fell into a deep depression following the execution. He performed one final hanging—that of Susan Newell, who had murdered a paperboy after he refused to give her a free paper—before he retired from his grim profession.

After retiring, Ellis wrote his memoirs. His first suicide attempt, by hanging, occurred after their publication in early 1924. A few years later, he took a role in a stage production about the crimes and death of murderer Charles Peace. Although the show eventually closed, Ellis used the set’s scaffold to continue staging his own reenactments. Unfortunately, this did little to improve his mental state, and in 1932, he tragically ended his life by slashing his throat with a razor blade.

1. Louis Congo

Louis Congo, once a slave in Louisiana, was freed by government officials and appointed the state’s executioner in 1725. His appointment was a symbolic act, meant to send a strong message—placing a former slave in control of life and death, especially over individuals of any race, served as both a statement of power and a striking blow to those who saw themselves as superior.

Congo’s name appears frequently in Louisiana records throughout the next 15 years. However, his fate remains unclear as he vanishes from historical accounts in the 1730s. It’s uncertain whether he retired, disappeared, or met a tragic end, but what is known is that his time in office was far from easy.

As executioner, Congo held significant power, from administering beatings as punishment to banishing individuals from the town or overseeing their execution by hanging or the breaking wheel. His position granted him authority, but it also branded him with the derogatory title of bourreau, one of the harshest insults of the time.

Just a year after assuming his role, Congo’s life was violently disrupted when three runaway slaves broke into his home and severely beat him. This attack wasn’t an isolated incident, and Congo found himself compelled to carry out the court’s judgment against his own assailants. His position as an executioner required that his punishments not only serve justice but also act as a stern warning against any assault on government officials.

The records detailing Congo’s actions as an executioner cease in 1737, marking the end of his documented involvement in Louisiana’s judicial system.