While some executioners have tried and failed to stay out of the spotlight, others have actively sought fame by authoring books, participating in interviews, delivering lectures, and even showcasing death machines to intrigued audiences (without the lethal consequences, naturally). Regardless, the enigmatic figure known as the 'man who walks alone' has always captivated public interest.

10. Edwin Davis

Hanging is a grim and brutal process. While the fall from the gallows is intended to snap the neck and cause instant death, it often fails to do so. Instead, the condemned may dangle for 10 to 20 minutes, gasping for air, choking, and losing control of their bodily functions before finally succumbing to asphyxiation. To eliminate this gruesome ordeal, New York state introduced electrocution in the late 19th century.

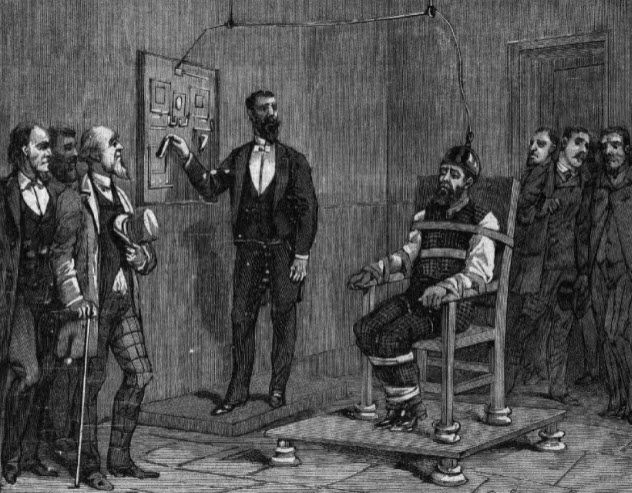

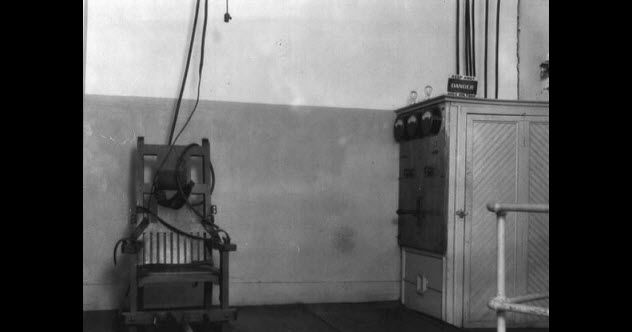

On August 6, 1890, New York’s Auburn Prison witnessed the first execution by electric chair. William Kemmler, a convicted murderer, bowed ceremoniously to the witnesses before sitting down. He reportedly stated, 'I believe dying by electricity is far better than hanging. It won’t cause me any pain.' Addressing Warden Charles Durston and electrician Edwin Davis, he added, 'Take your time and do it properly.'

At the signal, Davis activated the switch, delivering a 17-second electric shock. However, when the current ceased, Kemmler was still alive, his chest rising as he gasped for breath. Davis applied a second, much longer shock, lasting several minutes. The room filled with the smell of burning flesh, and one reporter fainted. When the electricity was finally cut off, Kemmler was dead, and the execution was deemed successful.

Davis went on to oversee the electrocution of over 300 convicts across multiple states before retiring in 1914. His victims included Martha Place, the first woman to die in the electric chair, and Leon Czolgosz, the assassin of President William McKinley. Davis personally constructed the first electric chair and, proud of his invention, even sought a patent for it, dubbing himself 'the father of the electric chair.'

However, the true 'father' of the electric chair was inventor Thomas Edison. While Edison is remembered as a brilliant and benevolent engineer, he was also a fierce competitor. In the 1880s, he promoted a direct current (DC) electric transmission system, while his rival, George Westinghouse, championed alternating current (AC).

To undermine his competition, Edison initiated a public relations campaign to portray alternating current (AC) as hazardous. He organized a series of strange experiments, electrocuting dogs, cats, farm animals, and even an orangutan with lethal AC shocks. He then advocated for the use of AC in executions, branding it as a humane method and sarcastically suggesting it be called 'Westinghousing.'

9. John Hulbert

John W. Hulbert Jr., a protégé of Edwin Davis, succeeded his mentor as New York’s executioner. He carried out over 140 electrocutions before stepping down in 1926. At his retirement, he reportedly confessed, 'I grew weary of taking lives.'

He earned $150 per execution, sometimes as much as $450, a substantial sum for that era. However, the emotional toll of the job may have outweighed his financial gains.

Hulbert took extreme measures to safeguard his anonymity. He avoided interviews and refused to let the media capture his image. Despite his efforts, journalists relentlessly pursued him.

Over time, the pressures of his role took a toll on Hulbert. He kept a firearm, fearing retaliation from associates of those he had executed. On nights of executions, he insisted on dining at the same restaurant, ordering the same meal, and being served by the same waiter, whom he tipped generously. His paranoia stemmed from a fear that his food might be poisoned.

On one occasion, Hulbert collapsed while performing his duties. After being revived by the prison doctor, he completed the execution and subsequently spent a week recovering in the hospital.

In 1929, three years after resigning, Hulbert went to his basement and took his own life. Following his death, a New York newspaper noted that he was never observed shaking hands with anyone.

8. Robert Elliott

When Robert Elliott took over Hulbert’s role as New York’s executioner, he initially attempted to remain anonymous. However, less than a year into his job, a journalist tracked him from Sing Sing prison to his home in Queens, exposing his identity. His mailbox soon overflowed with hate mail, and shortly after, a bomb destroyed his front porch.

Elliott reportedly stated, 'I’d prefer administering the electric current to speaking with the press.'

Despite the challenges, Elliott had a lengthy career. While working for New York, he also offered his services to six other states in the Northeast. Between 1926 and 1939, he executed 387 individuals, including Bruno Hauptmann (convicted of kidnapping and murdering Charles Lindbergh’s baby), Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (whose executions many considered unjust), and Ruth Snyder, along with her lover Judd Gray, who were convicted of murdering Snyder’s husband.

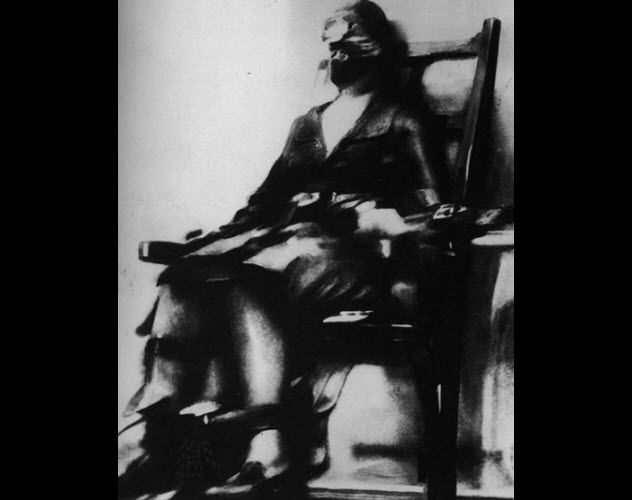

During Snyder’s execution, a witness managed to sneak a camera into the viewing area by securing it to his leg. As Elliott activated the electric chair, the witness lifted his pant leg and captured a now-famous photograph, which was published in the Daily News the following day.

Unlike Hulbert, Elliott remained unaffected by the emotional weight of his duties. He attended church on Sundays, enjoyed fishing in Long Island Sound, played bridge, and cultivated a stunning flower garden that became the envy of his neighborhood.

After his identity was revealed by the media, Elliott decided to write a book titled Agent of Death: The Memoirs of an Executioner. In it, he expressed his personal stance against the death penalty, arguing that vengeance should be left to God, not humans. He claimed he performed his role to ensure executions were carried out as humanely as possible.

7. Joseph Francel

Joseph Francel, Sing Sing’s executioner from 1939 to 1953, was a private man who avoided the spotlight. The Nashua Telegraph portrayed him as 'a reserved resident of the Catskill Mountains' and 'a soft-spoken traveling salesman from Cairo.' Despite his low profile, the 137 individuals he executed included some of the era’s most infamous criminals, thrusting him into public attention.

In 1944, Francel executed Louis 'Lepke' Buchalter, the nation’s most notorious labor racketeer and a key figure in the mob’s 'Murder, Inc.' On the same night, he also executed two of Lepke’s associates, Mendy Weiss and Louis Capone (unrelated to Al Capone), as well as two Brooklyn police killers, Joseph Palmer and Vincent Sallami, turning the death chamber into the evening’s grim focal point.

On June 19, 1953, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a married couple convicted of passing atomic secrets to the Soviets, were executed in Francel’s chair. Both maintained their innocence until the end. Julius died without complications, but Ethel required a second shock, sparking concerns that her death occurred several minutes into the Jewish Sabbath.

Later that summer, Francel resigned. As reported by the Milwaukee Sentinel, he informed the warden that he had faced 'too many threats and insufficient compensation.' Officially, he was paid the standard rate of $150 per execution.

6. James Van Hise

In 1907, New Jersey’s inaugural electrocution occurred at Trenton State Prison, with Edwin Davis operating the switch. Meanwhile, other state prisons continued to employ the services of James Van Hise, a gruff and experienced hangman.

Van Hise reportedly executed 250 individuals during his career and claimed to reporters that none of them remained atheists by the end. As reported in The Morning Call, he stated, 'Every single one of them embraced salvation just before their time came to depart this world.'

Concerned that he might be replaced by an electrician, Van Hise aimed to refine the gallows to make executions more humane. Instead of relying on the drop to break the neck, he suggested attaching a heavy weight to the rope, which would violently jerk the condemned into the air.

Van Hise was in a foul temper the day he introduced his new method. Edwin Tapley, convicted of killing his wife, approached the gallows singing a hymn. 'Hurry up! Hurry up!' Van Hise barked, as reported by the Wangaui Chronicle. Tapley attempted to share his final words of remorse, but Van Hise interrupted by placing a black hood over his head.

The hangman released the lever, sending the prisoner into a swinging motion. After seven minutes, a doctor checked Tapley and found him still breathing. Van Hise repositioned the rope around the prisoner’s neck and let him hang for another six minutes. Only then did the doctor declare Tapley dead.

'Van Hise was deeply embarrassed,' the Wangaui Chronicle noted. He attempted to shift the blame onto two ministers, claiming their conversation distracted him while he was adjusting the hood and noose.

5. Rich Owens

When a professional executioner from Little Rock arrived too intoxicated to perform his duties, prison guard Rich Owens seized his first opportunity to operate Oklahoma’s electric chair. 'I just walked over and flipped the switch as if I’d been doing it forever,' Owens later recounted to Ray Parr of the Daily Oklahoman. 'Someone had to do it since the man was already seated and waiting. I believe no one should have to wait longer than necessary.'

From 1918 to 1947, Owens executed 65 inmates. Over his lifetime, he killed 10 others, faced murder charges four times, and was acquitted each time. His first killing occurred at age 13 when he caught a thief trying to steal his father’s horse.

Owens once executed a prisoner who had saved his life by defending him against six attacking inmates. The next morning, Owens insisted on receiving his $100 bonus and gave the money to the executed man’s widow.

He also killed two inmates who attempted to use him as a shield during an escape. They stabbed him in the back to force him forward. When a guard shot and injured one of the escapees, Owens took the knife, stabbed one attacker, and bludgeoned the other to death with a shovel as the man pleaded, 'Please don’t kill me, Mr. Rich.'

'What kind of prison would this be without the electric chair?' he asked reporter Parr. 'It’s a satisfaction to execute some of these despicable individuals. Just consider the harm they’ve caused others.'

4. Jimmy Thompson

Jimmy Thompson, Mississippi’s executioner in the 1940s, was unapologetically open about his work. Journalists often described the heavily tattooed former carnival worker as 'colorful.' After executing Willie Mae Bragg, a convicted wife-killer, Thompson proudly remarked that the man died 'with tears in his eyes, thanks to the meticulous care I took to ensure he received a proper and thorough execution.'

Mississippi transitioned from hanging to electrocution in 1940. While hangings were conducted in the county where the sentence was issued, the state legislature decided to maintain this practice for electrocutions. As a result, Thompson traveled across the state in a new pickup truck equipped with a generator and a sturdy chair fitted with straps and electrodes.

A former convict himself, Thompson carried out executions in prison yards rather than in public. Despite this, crowds would gather outside to witness the lights flicker during the process. To satisfy public curiosity, Thompson occasionally conducted nonlethal demonstrations of his equipment. During these displays, he proudly claimed that he provided each condemned individual 'the most dignified death imaginable.'

Thompson earned $100 for each execution he performed and $200 for what he referred to as 'a double header.'

It was said that Thompson would go on a drinking spree after every execution. The following morning, he often spent a significant portion of his earnings on bail to resolve drunk-and-disorderly charges.

3. Jerry Givens

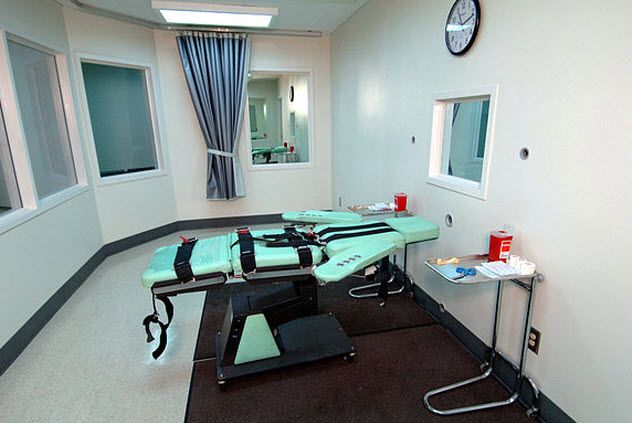

In the age of lethal injection, most executioners in U.S. prisons have kept their identities hidden. Jerry Givens, however, is an exception. As Virginia’s former executioner, he operated both the electric chair and lethal injection equipment. He later revealed himself by becoming an outspoken opponent of the death penalty.

'The worst decision I ever made was accepting the role of executioner,' Givens confessed to The Guardian. 'Life is fleeting... Death will come to us all. There’s no need for us to take each other’s lives.'

Givens was working as a prison guard when he agreed to become Virginia’s executioner. At the time, the state had no death row inmates, as the death penalty had only recently been reinstated. However, death row soon filled up, and Givens went on to execute 62 men, starting with electrocution and later transitioning to lethal injection.

He carried out his duties for 17 years. Toward the end, he began experiencing flashbacks and emotional distress. Although he considered resigning, he was charged with money laundering before he could do so. Givens lost his job and served four years in prison, though he maintains his innocence to this day. This experience motivated him to become an advocate against capital punishment.

Givens has also drawn attention to what psychiatrists now term 'executioner’s stress,' a form of post-traumatic stress disorder that can affect guards, wardens, and others involved in state-sanctioned killings. 'The executioner is the one who suffers,' he explained to Newsweek. 'The person who carries out the execution is haunted by it for life. They must bear that weight. Who would willingly take on such a burden?'

2. John C. Woods

After executing 10 high-ranking leaders of the Third Reich, who were sentenced to death during the 1946 Nuremberg trials, U.S. Army Master Sergeant John Clarence Woods considered himself a hero. 'I executed those ten Nazis,' he declared to Time magazine. 'And I take pride in it... I wasn’t nervous... In this line of work, you can’t afford to be.'

While Woods boasted of a much higher number, historians estimate that he executed 60 to 100 men during World War II and briefly afterward. In addition to the Nuremberg trials, he carried out executions of war criminals in Rheinbach, Bruchsal, and Landsberg. He also hanged American soldiers convicted in court-martials across Europe.

The Nuremberg executions were not without controversy. When Julius Streicher, a Nazi propagandist, was heard groaning during his hanging, Woods stepped behind the curtain that hid the execution from witnesses. Many believe he pulled on the body to speed up death.

Since then, Nazi sympathizers have accused Woods of intentionally mishandling the execution to cause prolonged suffering, though they lack any solid proof.

Woods never had the opportunity to address these accusations. He died four years after the Nuremberg trials, electrocuted accidentally while fixing lighting equipment.

1. T. Berry Bruce

When Mississippi adopted gas chamber executions in 1955, the executioner’s identity became classified. However, in the early 1980s, leaked legal documents from the governor’s office revealed that T. Berry Bruce, a produce salesman, had been administering the gas since 1957.

Bruce, a hardened veteran of World War II and the Korean War, executed over a dozen individuals before retiring in 1964. For most of his career, his role as an executioner remained a secret, unknown even to his wife. His identity was uncovered when executions resumed after a 19-year hiatus. Journalists sought him out for interviews, and Bruce was surprisingly open.

He told Southam News that he felt no guilt about potentially executing innocent people. 'That’s the court’s responsibility,' he said. 'Not mine... After I gas him, I can go out and enjoy a pint of whisky without a second thought.'

Soon after that interview, Bruce briefly returned to his role. However, the 1983 execution of Jimmy Lee Gray, a convicted child rapist and murderer, was severely mishandled, leading the state to adopt lethal injection. Guards had secured Gray in the gas chamber, and Bruce dropped cyanide pellets into acid, releasing lethal fumes.

However, Gray did not slip quietly into unconsciousness as anticipated. Instead, he struggled for breath for eight minutes and repeatedly struck his head against a metal bar behind the chair. The scene was so horrifying that the warden ordered witnesses to leave before Gray was officially declared dead.

Some unsettling accounts suggest that Bruce was drunk when he activated the gas.