The history of early flight is truly captivating. While numerous aircraft succeeded, there was no clear agreement on the optimal design for an airplane. As a result, aviation pioneers experimented with various unconventional ideas in their pursuit of the next big breakthrough. This spirit of experimentation continued into World War I, a time when the role of airplanes in warfare was still being defined. A wide array of aircraft models soared through the skies during the conflict. This list highlights some of the most intriguing and outlandish flying machines from the pre-World War II era and the early days of modern aviation.

10. Armstrong Whitworth Ape

Experimental aircraft are costly ventures. Most are designed for a single specific flight regime or to test one particular idea. In aviation's early years, this posed a major challenge, as many experimental aircraft were poor designs that failed miserably even during concept testing. Struggling with funding and manpower, the British Royal Aircraft Establishment sought alternative methods to test aerodynamics without needing to construct an entirely new airplane for every query. To this end, the RAE called upon airplane manufacturers to create an “infinitely” adjustable aircraft capable of answering all their aerodynamic questions.

Armstrong Whitworth eagerly seized the opportunity. Having supplied various aircraft models for the RAF during World War I, they found themselves struggling with postwar defense cuts and securing new contracts. To fulfill the RAE's request, they designed the Ape, a fully adjustable biplane. The Ape truly lived up to its billing. Engineers could modify the fuselage by adding or removing bays, adjusting its length. The wings were customizable with varying degrees of dihedral or could even be swept back. Uniquely, the tail section moved as a single unit, allowing for adjustments in pitch during flight, depending on the test at hand. Unsurprisingly, these features resulted in the Ape being an extremely unattractive plane.

Despite the adjustable features fulfilling the design specifications, the Ape suffered from a woefully underpowered engine. With a top speed of just 145 kilometers (90 miles) per hour, the Ape was limited to experimenting with slow flight conditions, which proved unhelpful in developing faster, more advanced fighter aircraft. Armstrong Whitworth replaced the engine with a more powerful one for the second model, but the RAE demanded additional modifications, which negated the performance gains of the upgraded engine. After several months of testing, it became evident that the Ape wasn't effective in advancing aerodynamic research, and the project was eventually abandoned with no technological breakthroughs.

9. Sikorsky Ilya Muromets

Say what you will about Russian engineering, but history has shown that when it comes to constructing large military aircraft, the Russians certainly know their craft. The Ilya Muromets was the largest plane of its time, pioneering numerous aviation features that we now take for granted. Initially, Igor Sikorsky designed the Muromets as a grand, four-engine passenger plane that was meant to revolutionize air travel. When it first flew in 1913, it showcased a range of never-before-seen features. For the first time, the passenger cabin was equipped with electricity and heat powered by a small, wind-driven turbine. Additionally, the Muromets featured the world’s first airborne toilet, housed in a small bedroom at the back of the plane.

The first flights of the colossal biplane were a resounding success. The Muromets flew across Imperial Russia, serving as a powerful propaganda tool. Sikorsky’s vision had materialized. However, just before passenger flights could begin, World War I broke out, and the Muromets was re-purposed as a heavy bomber. This transition made perfect sense. With a range and payload far superior to contemporary bombers, the Muromets quickly outclassed most other aircraft. Sikorsky equipped the biplane with defensive machine guns and a rudimentary bombsight. Training crews proved difficult, as no one had flown such a massive aircraft before. After a challenging adjustment period, a squadron of Muromets was established, becoming the first four-engine bomber squadron and the world’s first dedicated strategic bombing unit.

In action, the Muromets proved to be an exceptionally potent weapon. Bombing raids were carried out throughout the war, with rumors suggesting that a single Muromets bombing run could render a ground position unusable for weeks. The bomber’s robust design made it nearly impervious to enemy fire, creating a legendary reputation comparable to its namesake (a heroic figure from Russian folklore). Muromets crews fought bravely throughout the war and even participated in the subsequent Russian Civil War.

Looking back, the significance of the Ilya Muromets cannot be overstated. It not only introduced groundbreaking concepts in commercial aviation, but it also demonstrated that strategic bombing was a viable and effective tactic. In the following world war, the principles established by the Muromets would play a crucial role in shaping the course of the conflict.

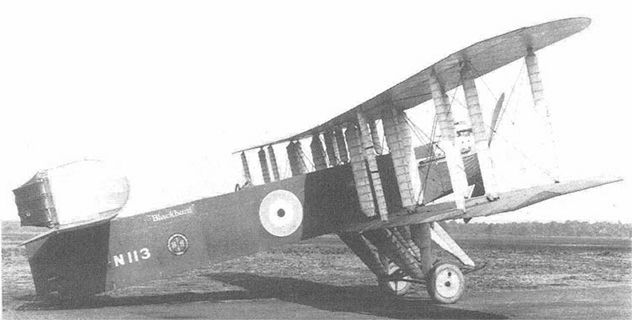

8. Blackburn Blackburd

Naval aviation was still in its early stages during World War I. While most other aspects of aerial combat were rapidly evolving, naval aviation faced significant technological challenges right from the start. No country had purpose-built aircraft carriers at the time, so every nation had to rely on modified ships to carry airplanes. Most large naval aircraft were underpowered, and none of the ships were long enough to provide an adequately long runway for landings. As a result, the flight profile for a large naval torpedo bomber was to take off only in a strong headwind, fly to the target, conduct the attack, and then either return to the ship or find a land base. The return was the tricky part. Pilots often had to ditch their planes in the water, hoping for recovery. Generally, this type of flight plan was avoided.

This is where the Blackburn Blackburd came into play, designed to advance British naval aviation into the next generation. As the war unfolded, naval commanders grew increasingly concerned that existing torpedo bombers could only carry small warheads. The Blackburd was developed to carry the Mark VII torpedo, one of the largest in the fleet. Blackburn’s design was as straightforward as possible, taking the form of a slab-sided box with no tapered surfaces. It was undeniably ugly but highly practical. The large wings could be folded back to fit into a ship’s hangar, and it had the capacity to carry the torpedo.

Unfortunately for the Blackburd pilots, the plane was designed to ditch in the water beside its home ship. Upon takeoff, the landing gear was ejected into the water, forcing the pilot to commit to an inevitable water landing. If the landing was successful, the unlucky pilot would have to wait by the plane, hoping the ship could retrieve both him and the bomber before they both sank underwater. When the first Blackburd was delivered, it crashed on its initial test flight. With the proposed engine and torpedo, the aircraft was simply too heavy to control and flew exactly as you might expect from a box-shaped airplane. The Navy was disheartened by the design and rejected it, sparing countless pilots from the grim fate of intentionally crash-landing into the sea.

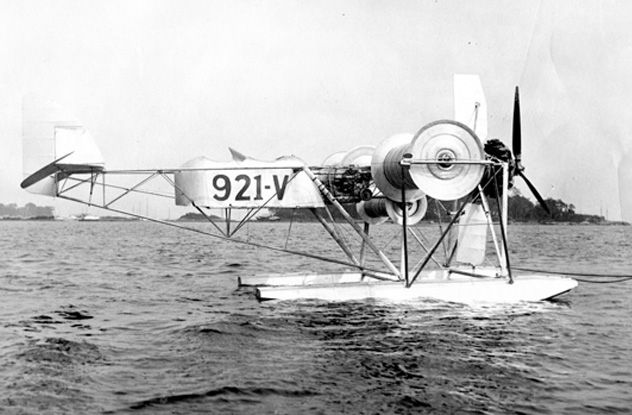

7. Blackburn TB

Zeppelins played a pivotal role in World War I's strategic warfare. Before high-performance interceptors were widely available, zeppelins could bomb their targets with little opposition. These massive balloons acted as flying fortresses. At the war’s outset, German commanders launched zeppelin attacks on England, instilling enough fear in the Admiralty to prompt the development of aircraft specifically designed to combat the ‘zeppelin threat.’ Blackburn answered this call by creating the most specialized airplane in history. The aptly named TB was a twin-hulled, long-endurance, fire-dart-equipped floatplane, built to intercept zeppelins.

To ensure the airplane had long endurance, engineers opted for a twin-engine configuration. However, rather than housing both engines within a single fuselage, they made the unusual decision to place two separate fuselages side by side. In the pre-radio era, this design meant the crew could only communicate through hand signals. Instead of using guns to bring down the zeppelins, the TB crews would have deployed the Ranken dart, a hand-dropped explosive designed to puncture the zeppelin's skin. Once inside, three spring arms would secure the dart in place, triggering a small charge into the balloon’s gas chambers. This would cause the gas to ignite, leading to the zeppelin’s fiery descent. Though the dart may seem peculiar, it was actually quite effective against German balloons and remained crucial until airborne cannons and incendiary rounds came into use.

The main issue with the Ranken darts was that pilots had to be positioned above the zeppelin to use them effectively. This posed a significant challenge for the TB. Its underpowered engines struggled to generate enough thrust, and its maximum altitude was far below the service ceiling of the zeppelin. The TB was also incredibly slow and could have easily been outrun by German airships. Without the necessary service altitude, the TB was practically useless, and the nine prototypes never saw any combat. The Admiralty soon shifted their focus to other alternatives.

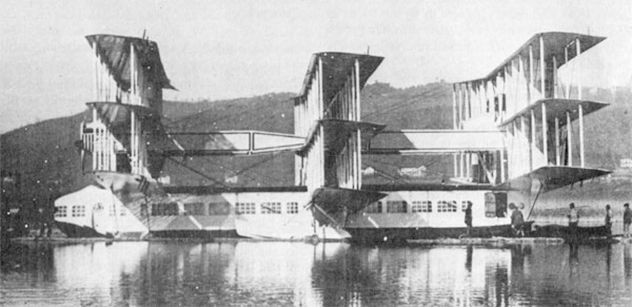

6. Caproni Ca.60

Gianni Caproni was a pioneering force in aviation. During World War I, he built several biplanes for the Italian Air Force, particularly large multi-engine bombers. After the war, Caproni turned his attention to his dream of creating a massive passenger airplane. For years, he had promised a 100-passenger aircraft that could fly people across the Atlantic. To make this vision a reality, Caproni opted for a design with nine wings and eight engines, creating a unique blend of seaplane and houseboat with the Ca.60.

After years of design and construction, the Ca.60 was finally ready to take flight. Powered by the impressive Liberty 12 engines, the aircraft boasted a wing area of over 800 square meters (8,500 ft). Caproni received widespread support from the press, government figures, and even the U.S. ambassador to Italy, who saw the seaplane as a glimpse into the future. Testing began at Lake Maggiore in 1921, but the first flights were plagued by bad weather and issues with the lower wings. However, on March 2, the Ca.60, with ballast on board, briefly took to the air. It flew smoothly and was able to land safely after a short flight.

On March 4, a second test flight was attempted. As the Ca.60 reached its top speed, it struggled to lift more than a few feet above the water. Suddenly, the enormous plane nose-dived into the lake, breaking apart instantly. Thankfully, the test pilot survived the crash with minor injuries, but the Ca.60 was completely wrecked.

The cause of the crash remains a mystery. Some sources claim the pilot stalled the plane, while others suggest he crashed while attempting to avoid a tugboat on the lake. The most plausible explanation is that the ballast inside the fuselage came loose, unbalancing the aircraft. Regardless of the cause, the Ca.60 was stored in a hangar, where it was eventually destroyed by an unexplained fire. Caproni never attempted to rebuild the aircraft, and the dream of transatlantic flight had to be put on hold.

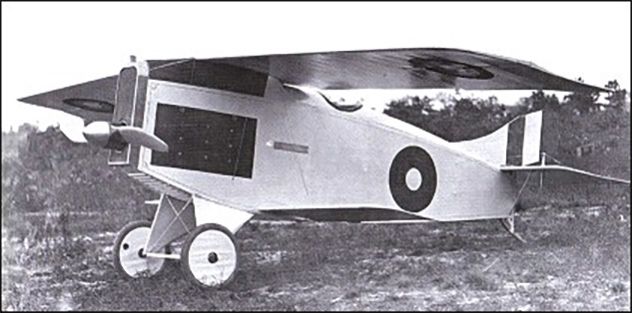

5. Christmas Bullet

William Whitney Christmas was a medical doctor who decided to make a drastic career shift into aviation. While career changes into aviation were not unheard of in the early days of flight, most of those who entered the field had some sort of relevant training. Dr. Christmas, however, lacked any knowledge of aerospace principles and had a penchant for exaggerating the truth. He claimed to have built his own airplane in 1908 and 1909, with the first one supposedly lost in a mysterious fire. Although only the 1909 model was confirmed to have been built, Dr. Christmas managed to raise enough funds to start his own aerospace company.

At the time, aircraft needed extensive struts and wires to keep the wings attached to the fuselage and ensure stability. Dr. Christmas, however, was convinced that airplane wings should be left unattached and began advocating for biplanes without struts. In 1915, he boldly proclaimed that such planes would be the largest ever made, and claimed European nations had already placed orders for his so-called “Battle-Cruisers.” Despite this, he began constructing a small fighter prototype for the U.S. Air Force. Dubbed the Christmas Bullet, the tiny plane was designed to reach a top speed of 317 kilometers (197 miles) per hour, surpassing the capabilities of contemporary aircraft. By promising a New York senator that the plane would be used to kidnap Kaiser Wilhelm II, Dr. Christmas secured a prototype Liberty 6 engine from the Army, which was intended only for ground testing. He built the Bullet around this engine and prepared for a test flight.

By this time, World War I had already ended, but Dr. Christmas still had the engine and arranged for a test flight with a pilot. However, shortly after takeoff, the wings detached from the aircraft, sending it crashing to the ground. The pilot died, and the Liberty 6 engine was destroyed. Undeterred by this failure, Dr. Christmas set about constructing a second prototype and convinced the Army to provide him with a new propeller, never mentioning the loss of the previous engine.

After a series of media appearances, the second prototype of Dr. Christmas's airplane was flown, but it resulted in the same failure as the first. With two pilots now dead from his aircraft's flaws, Dr. Christmas finally called it quits. However, before giving up entirely, he managed to get the Army to buy the patent for $100,000. Although he never achieved a successful flight, Dr. Christmas continued designing absurd airplanes for the rest of his life, all the while without a shred of knowledge about the principles of aerospace engineering. Luckily, none of his other designs were ever tested.

4. AEA Cygnet

When the Wright brothers ushered in the era of powered aviation in 1903, not everyone agreed that their choice of a powered biplane was the best—or even the most practical—design. Among those skeptical of the Wrights' invention was Alexander Graham Bell, the renowned inventor of the telephone. Bell acknowledged that the Wright brothers had come up with an interesting concept, but he believed it was not versatile enough to make powered flight a mainstream reality. In response, Bell founded the Aerial Experimental Association (AEA), a group made up of young men from both Canada and the United States, eager to experiment with new—and presumably better—ideas in aviation.

One of Bell’s most prominent ideas was the tetrahedral box kite. Unlike the Wright brothers' airfoil design, Bell envisioned an airplane that would feature a massive stack of tetrahedral cells. The AEA constructed and tested a large kite based on this concept in 1907. The kite was towed behind a motorboat with an AEA test pilot at the helm, reaching a height of 50 meters (170 ft). Encouraged by this success, the AEA decided to modify the kite to accommodate an engine, resulting in the Cygnet. With over 3,000 tetrahedral cells, the Cygnet was a striking and intimidating sight, but the AEA saw it as the future of aviation.

The first attempts at flight did not go as planned. The Cygnet refused to leave the ground. By adding an engine, the AEA had disrupted the lift characteristics of the tetrahedral design. After numerous tests, Bell concluded that the AEA should focus its efforts on biplane designs instead.

Turning their attention away from the Cygnet, the AEA shifted focus to the Silver Dart biplane, powered by the Cygnet’s engine. Once the Silver Dart demonstrated its airworthiness, the AEA returned to testing the Cygnet. On one of these attempts, the Cygnet achieved flight but only reached an altitude of 1 meter (2 ft). During the subsequent test, the tetrahedral structure collapsed, leaving the plane beyond repair. With this failure, Bell and the AEA realized that the Cygnet was an aviation dead end and decided to abandon it in favor of more practical designs.

3. Flettner Airplane

In the 1830s, chemist H.G. Magnus made an intriguing discovery: when a cylinder or sphere rotates in a fluid (like air or water), it generates a sideways force. This explains why a spinning sphere dropped from a great height will veer off its direct downward path. If applied correctly, the Magnus principle can also generate lift. A rotating cylinder or sphere, depending on the speed and direction of its spin, can create lift that in certain conditions may surpass that of a traditional wing. Inspired by this, German engineer Anton Flettner saw potential in using this principle for aviation.

Flettner had already explored the Magnus effect with success on boats, where replacing traditional propellers with rotating cylinders provided propulsion, though not more efficient than a regular propeller. Using this principle, Flettner set out to design an airplane. His creation, the Flettner airplane, replaced conventional wings with large spinning metal cylinders. The aircraft was powered by two engines—one for a standard airscrew and another to rotate the cylinders. Though the airplane should theoretically have flown, there are no records of a test flight. Modern aviation enthusiasts have since built remote-controlled versions of the Flettner airplane, which are capable of flight, proving the validity of its underlying principles.

While the results of the test flight remain unknown, Flettner shifted his focus to helicopters. During World War II, he worked on designing helicopters for the German Luftwaffe. Although his designs didn't reach mass production, they were considered important precursors to modern helicopter technology. After the war, Flettner continued designing helicopters for the United States, including the successful HH-43 Huskie. The fate of the Flettner airplane remains a mystery, but it presents an intriguing concept for alternative aircraft design.

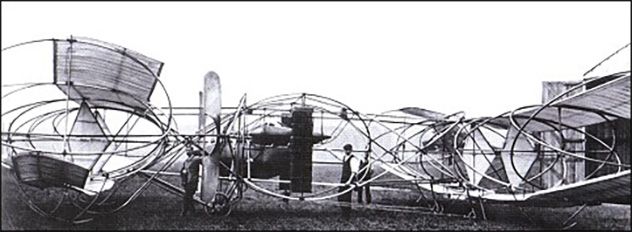

2. Seddon Mayfly

The Seddon Mayfly, resembling a modern piece of installation art more than a practical aircraft, was created as part of a Daily Mail competition to build the first airplane capable of flying between Manchester and London. Enthralled by the possibilities of aviation, sailor John W. Seddon crafted a paper model of what he believed to be the perfect airplane design. Taking time off from the Royal Navy, he enlisted the help of a fellow engineer to bring his paper concept to life.

The Mayfly had a relatively traditional configuration. It featured two massive banks of curved biplane wings, connected at the center by the cockpit and engines. However, the unique feature of the design was its bracing. Seddon was convinced that high-tensile metal hoops would provide stronger support for the wings than the conventional wood and wire braces. The Mayfly's construction required 610 meters (2,000 feet) of tubing. As a result of this innovative design, the six-seat airplane became the largest and heaviest airplane in the world. English aviators were filled with optimism, believing that if the Mayfly took flight, it would give them a crucial edge over their American and European counterparts.

Unfortunately, the Mayfly never achieved flight. Despite its impressive design, the wings' lift was insufficient to raise the heavy metal frame off the ground. During the initial high-speed ground test, a wheel collapsed, damaging the airframe. Seddon began repairs but was called back to the Navy. With Seddon absent, the Mayfly was neglected, left to gather dust in a hangar. Ultimately, the airplane met a sad fate when it was disassembled by souvenir hunters.

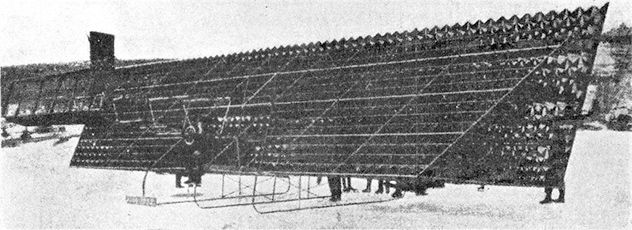

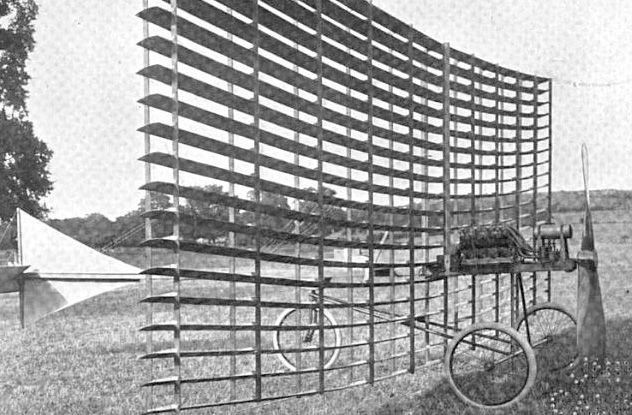

1. Philips Multiplane

In the early days of aviation, not everyone embraced the Wright Brothers’ design for the airplane. Horatio Philips, for example, had a different vision. He believed that an ideal airplane would require a multitude of wings working together to generate lift. Philips began working on his concept before the Wright Brothers and his first step was creating his own wind tunnel, which became one of the most powerful and efficient of its time. This innovation allowed him to test various airfoil designs to determine which ones were the most effective.

In 1891, Philips secured one of the earliest patents for a modern wing shape and started developing an airplane based on his research. After wind tunnel tests showed that thin, high-aspect ratio wings could generate enough lift, Philips constructed an unmanned aircraft featuring 50 wings. This plane was mounted on a rotating arm that allowed it to travel in a circular path. It was able to lift approximately 180 kilograms (400 lb). While the airplane proved highly unstable on the ground, Philips remained convinced that his Multiplane design was the future of flight.

It wasn’t until 1904 that the first manned version of the Multiplane was ready for its test flight. Powered by an unconventional coal engine, this airplane featured 20 wings stacked on top of each other. During the flight, the plane managed to lift off the ground and traveled 15 meters (50 ft) before gently returning to the earth.

Undeterred by this initial failure, Philips set about creating a new version of his Multiplane. This time, his design included an astonishing 200 wings, giving the plane a box-like appearance. In 1907, the new Multiplane took to the skies and flew for 150 meters (500 ft), marking the first powered flight in the United Kingdom. While this flight was a significant milestone in aviation history, the aircraft still faced serious stability issues, making it nearly uncontrollable in flight. Despite the challenges with his airplanes, Philips's pioneering work on airfoils had a lasting impact on future aviation innovators.