They were the largest flying creatures ever to exist. Pterodactyls soared across the skies from about 230 million to 66 million years ago, yet left behind a sparse fossil record. Each new bone unearthed sheds light on the lives of these predatory reptiles.

These findings are reshaping our understanding of how pterosaurs appeared, lived, and eventually disappeared. However, their full story remains shrouded in mystery and debate. Few animals stir the imagination of researchers like pterodactyls do.

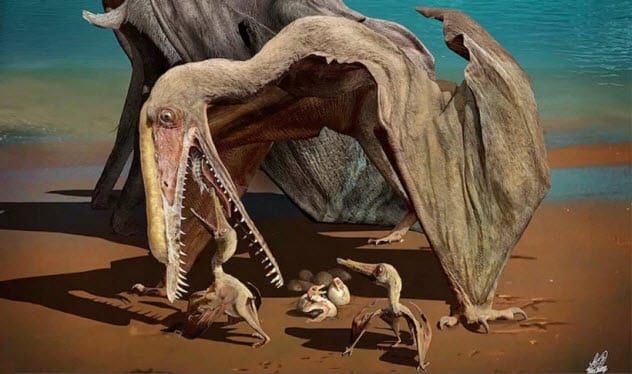

10. Flightless Juveniles

Scientists continue to debate whether pterodactyls could fly immediately after hatching. However, a 2017 discovery of preserved eggs put that theory to rest. About 16 eggs were found in remarkable condition, allowing 3-D scans to reveal complete skeletons. While the thighbones were robust, the bones supporting the flight muscles were underdeveloped.

This discovery suggests that the hatchlings could walk but were unable to take flight. Additionally, none of the young pterodactyls had teeth. This lack of teeth, combined with their flightless nature, would have made the newborns particularly vulnerable.

Another discovery hinted at parental care. Near the site where the 120-million-year-old eggs were found in China, adults of the same species were uncovered. These included both male and female H. tianshanensis.

The large number of eggs found in the area—over 200—suggests a colony-based breeding system. The soft shells of the eggs further indicate that, like modern reptiles, pterodactyls likely buried their eggs to protect them from drying out.

9. Enigmatic Species the Size of Airplanes

In 2017, paleontologists ventured into the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, targeting a rich fossil site. The area had never yielded a pterosaur before, so they were surprised when enormous neck bones emerged.

These were the cervical vertebrae of such immense size that the creature was believed to have been as large as a small plane. The species remains unidentified, but it lived about 70 million years ago and was likely one of the largest pterodactyl species to have ever existed. Estimates suggest the animal ruled the skies with an 11-meter (36 ft) wingspan.

However, confirmation must wait, as the rest of the body is still missing. It's also possible that the species was average or small but developed oversized necks for an unknown reason. Nevertheless, the discovery confirmed that these flying predators were more widely spread than previously believed—it was the first of its kind found in Asia.

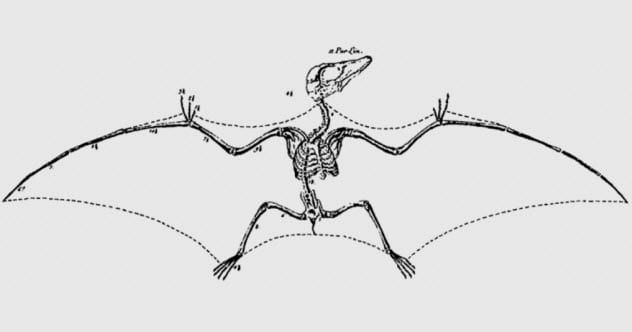

8. The Quail Study

In 2018, researchers challenged previous views about pterodactyls, specifically regarding the portrayal of their hip joints during flight. They referenced a 19th-century image of a pterosaur striking a bat-like pose and argued that such a position was impossible. They further claimed that nearly 95 percent of pterosaur and dinosaur reconstructions were inaccurate.

This conclusion was reached after comparing the thighbones of pterosaurs to those of the common quail. A quail's dead skeleton spreads like a bat's wings, though living muscles and ligaments prevent this pose in life.

The study was met with resistance. While birds are descended from a particular dinosaur lineage, pterosaurs are not dinosaurs. The controversial study suggested that pterodactyls had femurs similar to quails, but other experts pointed out that the structure surrounding the hip joint differed greatly from birds.

The study also ignored several important facts, including new findings about the reptiles' pelvic muscles and fossilized tracks that revealed how they walked. Moreover, the 19th-century sketch had already been dismissed as inaccurate years ago. While much about pterodactyls remains a mystery, this perplexing study involving quails and widely accepted mistakes has not advanced our understanding.

7. Their Breathing Was Peculiar

Pterodactyls didn’t breathe like humans. Their chests were unusually stiff, incapable of expanding to take in air or expel the old air. They had additional air sacs in their bones, much like birds, but their method of breathing was different. Birds use the movement of their sternum to control their breathing, but pterodactyls were simply too rigid to do so.

In recent years, the best insight came from living reptiles like crocodiles and alligators. They use a technique called the hepatic piston, involving the liver, which separates their lungs and digestive organs. When the liver contracts, it pushes the intestines downward, making room for the lungs to expand. When the belly ribs return the liver to its original position, the reptile exhales.

Pterodactyls may have employed a similar method. Despite their extremely tight chests—some species even had fused vertebrae and ribs, reinforced with mineralized tendons—this stiff structure worked in their favor. It strengthened their skeletons and minimized muscle mass, helping them achieve the status of the largest flying animals in history.

6. When Pterosaurs Resemble Turtles

In 2014, paleontologists Gerald Grellet-Tinner and Vlad Codrea discovered a 70-million-year-old species named Thalassodromeus sebesensis. Curiously, this genus had already been identified, with pterosaurs flying over Cretaceous Brazil approximately 42 million years earlier. If the two were indeed the same species, a large portion of its history appeared to be missing from the fossil record.

To explain this gap, Grellet-Tinner and Codrea proposed that migration, evolution alongside flowering plants, and island environments could have influenced the species. Despite their detailed scenario, the fossil from Romania didn’t quite fit.

In their study, the single fossil piece was described as a “snout.” However, upon review by other paleontologists, it became clear why the supposed new species couldn’t be a pterosaur—it was a turtle. The piece closely resembled the belly shell of a Kallokibotion, a turtle from the Cretaceous period.

Despite the well-known presence of Kallokibotion in Romania for nearly a century, and the unanimous disagreement with their conclusions, the authors stubbornly believed it was a pterodactyl. This misidentification posed a risk of confusing future research with an imaginary species that never existed.

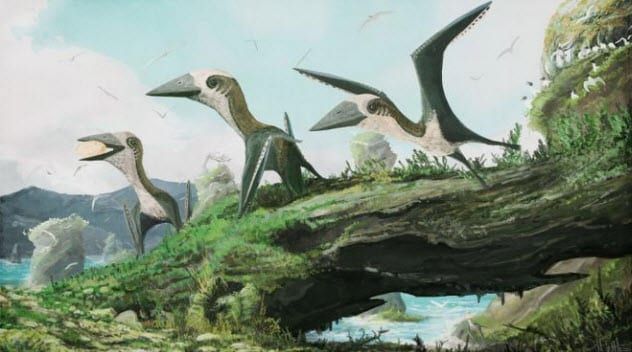

5. Pterodactyls of the Hateg Basin

The Hateg Basin was once an island where many animals evolved into dwarf versions of their larger relatives found elsewhere. During the age of dinosaurs, various species on Hateg were notably smaller than those on the mainland.

Curiously, however, the island was home to giant pterodactyls. The absence of large predators, such as tyrannosaurs, allowed these flying reptiles to dominate the island, becoming its apex creatures.

The tallest of these was Hatzegopteryx, which could have gazed directly into the eyes of a giraffe. With a wingspan of 11 meters (36 ft), it was surpassed by another pterosaur nicknamed “Dracula,” which had an impressive wingspan of 12 meters (39 ft).

In 2018, scientists identified the largest pterosaur jawbone ever found, and it came from Hateg. This fossil, which was discovered decades ago, was only recently recognized for its true significance and age—66 million years old.

This unnamed species, in its lifetime, boasted a jaw measuring 94–110 centimeters (37–43 in). However, this doesn't make it the largest pterosaur. Researchers estimate its wingspan was likely smaller—around 8 meters (26 ft)—which is less than the impressive spans of the giraffe guy and Dracula.

4. The Most Complete Skeleton

Pterodactyl fossils are incredibly rare. From the Triassic Period (220 million years ago), only 30 specimens have been discovered, often as isolated fragments. Recently, researchers extracted a large block from a Utah quarry known for its dense concentration of Triassic fossils.

In the lab, the team carefully removed several ancient crocodile remains before making an exciting discovery. Amid the 18,000 bones, they found a pterosaur—a partial face, an intact skull roof, a lower jaw, and part of a wing—making it the most complete pterosaur fossil ever found.

Scans quickly revealed a new species, Caelestiventus hanseni. This young creature sported 112 teeth and featured a bony protrusion on its jaw, likely to support a throat pouch similar to a pelican's. Its brain indicated sharp vision but a limited sense of smell.

The most significant discovery related to the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event. The rare fossil seemed linked to a species from the later Jurassic period, suggesting that C. hanseni‘s lineage survived a catastrophic event that wiped out countless species.

3. Killed In Their Prime

For years, it was believed that pterodactyls gradually faded into extinction. It was thought that by the time the dinosaurs disappeared 66 million years ago, pterodactyl numbers were already dwindling. However, a 2018 study disproved this theory.

The tale begins with Nick Longrich, a student who was obsessed with pterodactyls, later becoming a professional fossil researcher. While digging in Morocco, he unearthed a small bone. Having immersed himself in the pterosaur textbook to an almost religious degree, Longrich quickly identified the bone as belonging to the nyctosaurs, a smaller species of pterodactyls.

This discovery led to a series of findings, including seven new species from three distinct families. The most notable were the pteranodontid bones, a group believed to have vanished 15 million years earlier. These fossils hailed from the late Cretaceous, a period marked by an asteroid believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs.

The diversity of the finds proved that previous studies were incorrect. Pterosaurs didn't simply fade away. When the asteroid struck, they were thriving and varied. Despite flying through the skies for 150 million years, they couldn’t withstand the impact of the space rock.

2. They Were Fluffy

It's time to discard the outdated images of pterosaurs as leathery-skinned creatures. The truth is in—these flying reptiles were covered in feathers. Not just a few stray ones either. In 2015, researchers examining two remarkably well-preserved fossils discovered four distinct types of feathers. Found in China, these pterosaurs exhibited down feathers, single filaments resembling hair, clumps of filaments, and fluffy filaments with tufts in the middle.

While it's still uncertain whether these two pterosaurs belonged to the same species, both dated back to around 165–160 million years ago and were from the same fossil site. The specimens also contained preserved soft tissues. The pigment analysis revealed that the feathers had a rust-colored hue, potentially useful for camouflage or communication.

Much like modern birds, the feathers of pterodactyls could have served to insulate their bodies, enhance flight, or aid in tactile sensation. While they might share these feather types with some dinosaurs, pterodactyls had a unique distinction. This remarkable discovery of the feathered pair shifted the origins of feathers back by 70 million years.

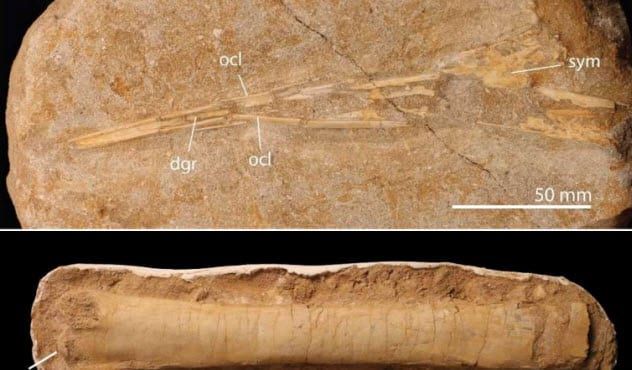

1. Cretaceous Surprise

By the close of the Cretaceous period, pterodactyls had reached their colossal size. Experts believed that intense competition in the ecosystem required these flying creatures to grow enormous to thrive. The role once played by smaller pterosaurs was gradually overtaken by birds.

In 2008, a fossil hunter made a surprising discovery on Hornby Island in Canada. The rock, about the size of a softball, contained visible vertebrae. After an initial inspection, the hunter speculated it could be a “flying something.” When researchers analyzed the specimen, they found it challenged the conventional view of Cretaceous pterosaurs. The vertebrae, aged 70–85 million years, featured unique traits linked to flight—traits not found in Cretaceous birds.

The remains pointed to a small pterodactyl, roughly the size of a cat. With only a few bones, researchers were cautious about naming a new species or placing it within the evolutionary timeline of pterosaurs. Still, this is a remarkable discovery. This tiny predator, which could still turn out to be a known species, existed at a time when it was thought no such creatures should have survived.