Launched in March 2009, the Kepler space telescope aimed to find planets beyond our solar system that resemble Earth in size. In 2013, when two of its four 'reaction wheels' malfunctioned, many believed the telescope's mission had come to an end.

Against the odds, the telescope has resumed its work. In addition to many other fascinating discoveries, it has identified over 1,000 exoplanets—planets that orbit stars other than our Sun.

10. The Exoplanet with the Longest Orbit

If you think your birthday takes forever to arrive, be glad you're not on Kepler-421b. This exoplanet holds the record for the longest year among all those discovered so far.

We detect an exoplanet by observing its shadow as it crosses in front of its sun. The greater the distance between an exoplanet and its star, the longer it takes to complete an orbit. This makes exoplanets like Kepler-421b more difficult to spot with our instruments, as its orbit rarely aligns with the star’s path.

So, how long would you need to wait for a birthday on Kepler-421b? Roughly 704 days. This is even longer than Mars' annual orbit, which lasts 687 days. And just in case you needed another reason not to settle there, Kepler-421b's surface temperature is -92 degrees Celsius (-135 °F).

9. The Compact Solar System

When we imagine a solar system, we often envision planets spaced far apart, as we see in our own solar system. However, Kepler has discovered a system where the planets are unusually close to each other.

This system features a star named Kepler-11, similar to our Sun. It has six planets orbiting it, all larger than Earth. The largest planet is comparable in size to Neptune, nearly four times the size of Earth.

The planet farthest from Kepler-11 has an orbit just slightly larger than Mercury's, the closest planet to our Sun. The remaining five planets have even smaller orbits, bringing them closer to their star than any planet in our solar system is to the Sun.

So, how do these planets manage to avoid gravitational interference with each other? They don’t. The entire system appears chaotic, with each planet's orbit affected by the others' gravitational forces. Although we can’t fully explain this chaotic yet stable system, it has persisted for millions of years, hinting that these orbits might be part of a perfectly synchronized pattern.

8. Enormous Solar Flares

When studying other stars, we often use our Sun as the primary reference. So when the Kepler space telescope observed solar flares on distant stars that were one million times more intense than those from our Sun, it caught the attention of scientists.

Solar flares from our Sun are caused by internal magnetic reconnection. Initially, scientists believed that for such massive solar flares to occur on other stars, a planet the size of Jupiter would have to pass close to the star. This idea is called the 'hot-Jupiter theory.'

However, scientists couldn't find any giant planets nearby to explain the observed solar flares, which seems to challenge the hot-Jupiter theory. Although the cause remains unclear, one thing is certain: we wouldn’t want our Sun to produce such colossal flares, as they would obliterate all life on Earth.

Ironically, scientists think that these massive solar flares could potentially kick-start organic life on distant planets, making them appealing targets for those searching for alien life.

7. The Planet with Four Suns

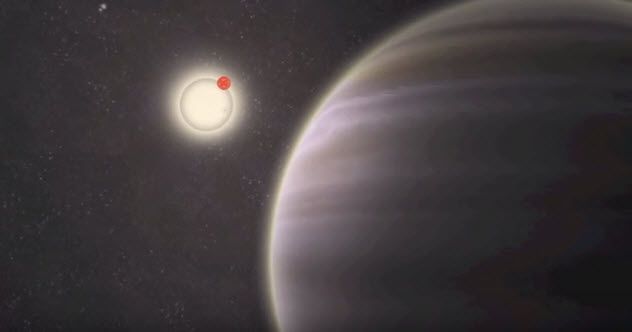

We’ve already covered Kepler-47c, a planet with two suns. But in late 2015, the Kepler space telescope made an even more exciting discovery—a gas giant slightly larger than Neptune, which is orbited by not one, but four suns.

Its very existence confounds scientists. They cannot fathom how this gas giant isn't being torn apart by the combined gravitational forces of four suns. They are also puzzled by how it maintains an 'apparently stable orbit,' which they hadn’t expected from a planet orbiting four suns.

Even more fascinating, the discovery wasn’t made by NASA. While the data came from the Kepler telescope, it was actually amateur astronomers from a group called Planet Hunters who combed through the data and identified this remarkable planet. Remarkably, it was their very first find.

The planet is named PH1, which stands for “Planet Hunters 1.”

6. The Super-Earth Orbiting an Orange Dwarf

When the Kepler space telescope experienced a critical failure a few years ago, many believed its mission had come to a halt. Yet, the telescope was revived and proved its worth by discovering a planet unlike any in our solar system.

This planet, named 'HIP 116454b,' is about 2.5 times the size of Earth and has 12 times its mass. Its density suggests that it could either be a 'water world' (75 percent water, 25 percent land like Earth) or a smaller, gaseous version of Neptune. If it is a water world, its close proximity to its star likely makes it too hot to sustain life.

This super-Earth orbits a type K orange dwarf star, which differs from the yellow dwarf like our Sun. Orange dwarfs have less mass but can live up to three times longer than yellow dwarfs. Despite its star being cooler than our Sun, HIP 116454b orbits so closely that its year lasts just nine Earth days, explaining why this super-Earth is so hot.

5. The Planet That Wobbles

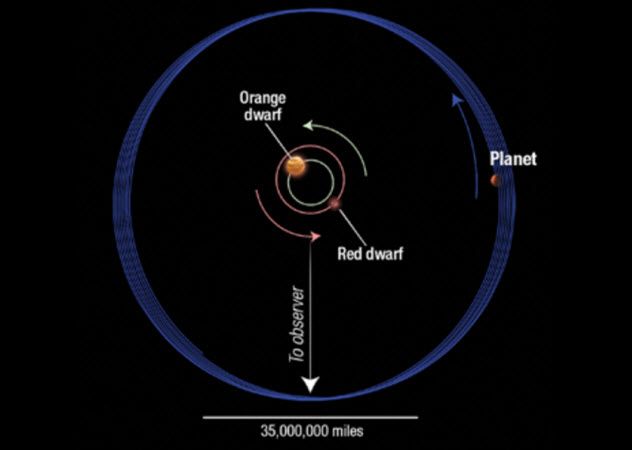

Kepler-413b is a gas giant with a mass up to 65 times that of Earth. However, the most fascinating feature of the planet is not its composition or size, but the peculiar angle at which it orbits.

As this gas giant orbits both an orange dwarf and a red dwarf (which is less massive and more stable than an orange dwarf), the planet tends to wobble on its axis, much like a spinning top. Kepler-413b's axis shifts by as much as 30 degrees every 11 years. In comparison, Earth's axis has only shifted by 2 degrees over the course of 26,000 years.

If Earth experienced an axis shift as extreme as Kepler-413b’s, it would result in chaotic changes to our seasons. Additionally, Kepler-413b orbits too closely to its star for liquid water to exist on its surface, rendering the planet uninhabitable for life as we know it.

4. The Total Number of Earth-Sized Planets in the Milky Way

Not all discoveries made by the Kepler space telescope are focused on individual planets or stars. Often, astronomers use the data to make broader predictions about our galaxy, the Milky Way. One such prediction is an estimate of the number of Earth-sized planets within the Milky Way.

From the data collected by the telescope, astronomers have concluded that 17 percent of the stars in the Milky Way host an Earth-sized planet. About 25 percent of the galaxy’s stars are home to a 'super-Earth,' and another 25 percent are orbited by a mini-Neptune.

With roughly 100 billion stars in the Milky Way, this means there are an estimated 17 billion Earth-sized planets out there. And this doesn’t even consider 'alien-Earths,' planets that could harbor life in ways we’ve yet to imagine.

3. The Bizarre Star That Sparked An Alien Hunt

The Planet Hunters were tasked with searching for planets, but one particular star—KIC 8462852—kept being flagged by observers as 'bizarre' and 'interesting.' Upon closer inspection, scientists discovered a sun exhibiting a shadow pattern that suggested a tightly packed stream of matter orbiting the star.

If the star had been young, this discovery might be explained as the 'matter soup' from which a solar system forms. However, this star was mature. By now, any solar system would have already formed, meaning the observed matter must have been generated after the star reached its mature stage.

Numerous theories were proposed but dismissed. For instance, it would be an extraordinary coincidence to witness a temporary sea of comets. Given that this unusual pattern appeared in only one star out of 150,000 recorded light patterns, scientists suspected something more was at play. That’s when someone suggested the objects might be alien structures designed to harvest the star’s energy.

Despite astronomers calling it a 'last resort' explanation, news outlets eagerly embraced the theory, triggering a surge of alien speculation on the Internet. The SETI Institute attempted to detect communications from the 'alien structures,' but they couldn’t find anything. While not all experts supported the alien theory, some continue to hold on to the improbable idea, convinced that the aliens are using a form of communication we can’t detect.

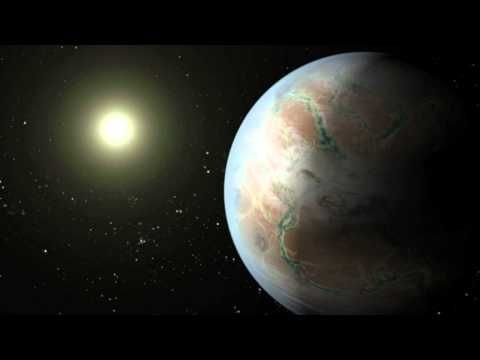

2. Earth 2.0

Known as 'Earth 2.0,' Kepler-452b is often referred to as a 'close cousin' to our planet. With five times Earth's mass and approximately 60 percent more width, Kepler-452b would make a person weigh twice as much as they do on Earth.

You might be able to lose that extra weight, though. Kepler-452b orbits a star that’s 20 percent brighter than our Sun, although it is the same distance from its star as Earth is from the Sun. This makes Kepler-452b a larger, hotter, and heavier version of Earth—but it’s still potentially habitable.

The potential of Kepler-452b is so intriguing that scientists at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute turned the Allen Telescope Array toward the planet, hoping to detect radio signals from alien life. However, they found nothing. As Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the SETI Institute, said in a webcast, 'That’s no reason to get discouraged. Bacteria, trilobites, dinosaurs—they were here, but they weren’t building radio transmitters.'

1. The Star Destroying A Small Planet

When astronomers discovered a planet with a 'tail' of matter trailing behind it, they were puzzled. After further analysis, they concluded that the tail was debris being torn off the planet as it was pulled apart by its host star.

Sadly for this planet, its star has turned into a white dwarf. When stars like our Sun—classified as small to medium-sized—reach the end of their life, they expand into red giants, shedding their outer layers before collapsing into hot, dense cores known as white dwarfs. Larger stars, on the other hand, transform into black holes or neutron stars upon dying.

When this particular star swelled into a red giant, it’s likely that the planets orbiting it were either engulfed by the expanding star or cast out into the cold void of space, becoming lifeless. The remaining planets—like the one observed by Kepler—now face the danger of having their matter ripped apart by the immense gravity of the white dwarf.

Our planet may meet a similar fate. If Earth survives the Sun’s transition into a red giant, scientists predict that our planet too will eventually be torn apart by the white dwarf the Sun will become.