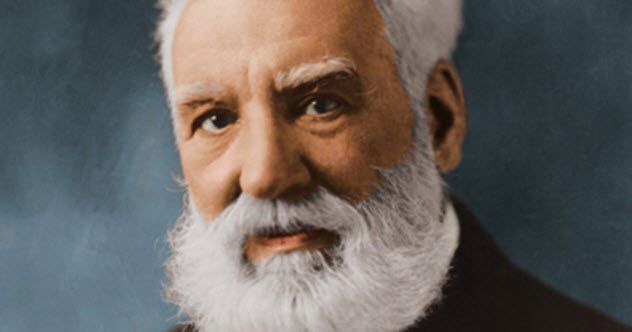

Though Alexander Graham Bell is widely remembered for his invention of the telephone, his true life's work revolved around the betterment of the deaf. Bell believed his legacy would be defined by his efforts for the deaf, from running a school for them to creating innovations aimed at enhancing their lives and advocating for life-changing policies. However, his actions led to widespread resentment among the deaf community.

Today, many in the deaf community view Bell as an antagonist. His legacy has been tainted with accusations, with articles labeling him a ‘huge jerk,’ claiming he ‘opposed deaf people’s rights,’ or even suggesting that he ‘despised the deaf,’

A man who devoted his life to aiding a community ultimately became seen as one of their greatest enemies. His story, filled with paradoxes, provides a window into the complex and often harsh realities of being deaf at the dawn of the 20th century.

10. He Advocated for Legislation Against Deaf People Reproducing

There are reasons behind the animosity some people in the deaf community hold toward Alexander Graham Bell. He wrote an entire paper warning about the emergence of a ‘deaf race.’ He described deafness as a ‘great calamity’ and proposed eugenics as the only solution, believing that deaf people needed to be eradicated.

Bell’s concern, in his view, was that deaf individuals were allowed to marry. He argued that ‘it is only reasonable to assume that the tendency toward deafness exists in a family containing more than one deaf-mute,’

While Bell didn’t advocate for the mass extermination of deaf individuals like Adolf Hitler, he did suggest that it should be illegal for two deaf people to marry. He wrote, ‘A law forbidding congenitally deaf persons from intermarrying would go a long way toward checking the evil.’

Bell’s primary concern was that enforcing such a law would be difficult. As a temporary measure, he proposed that deaf individuals should be kept separate from one another. They should be prohibited from attending schools for the deaf or learning from deaf teachers. If two deaf people never encountered each other, he argued, they couldn’t marry.

9. Even though his mother was deaf

Ironically, Bell’s own birth might never have happened if his own principles had been applied. While he opposed deaf people having children, Bell was the son of a deaf mother.

This seems paradoxical, but his mother’s experience actually helped shape Bell’s views on deaf eugenics. While the exact timing and cause of her hearing loss differ by account, she was not born deaf and therefore could not pass it on genetically. According to Bell’s beliefs, she would have been allowed to have children. Yet, if laws had strictly forbidden deaf people from reproducing, Bell himself would never have been born.

More significantly, Bell’s mother exemplified the kind of deaf person he envisioned. Her husband, Bell’s father, was the creator of Visible Speech, a phonetic alphabet designed to teach speech to the deaf. She mastered it with ease. She could speak and, impressively, was an accomplished pianist. Like Beethoven, she would press her ear to the piano to feel the vibrations and play.

For Bell, this was the ideal model of a deaf individual—someone fully integrated into the hearing world. This person would read lips, speak, and never outwardly reveal their deafness. The ‘deaf race’ Bell sought to prevent, in his view, consisted of people who communicated in sign language and lived apart from society.

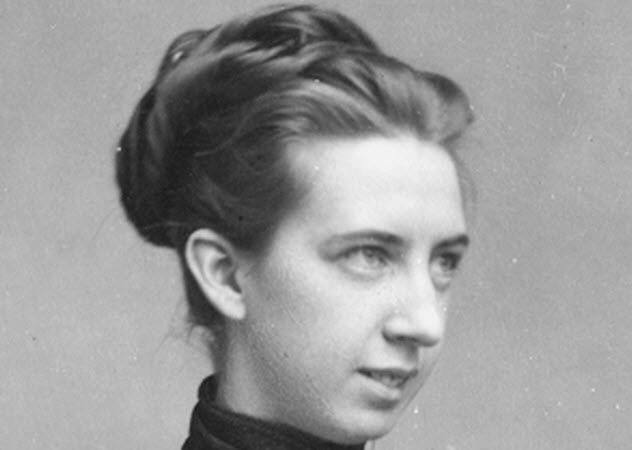

8. His Wife Was Also Deaf

Bell followed his father’s footsteps throughout his life. As he grew older, he expanded on his father’s ideas for Visible Speech and eventually took control of his father’s school for the deaf. In a similar fashion to his father, Bell married a deaf woman.

At the age of 27, Bell fell for 16-year-old Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, a student who had lost her hearing to scarlet fever as a child. However, she had learned to speak and lip-read.

Bell was enchanted by her voice and frequently mentioned it. In one letter, Mabel shared, “Mr. Bell said today my voice is naturally sweet.” In another, she expressed concern over her speech clarity, but Bell reassured her by saying, “The value of speech is in its intelligibility, not its perfection.”

Bell had a complex connection with the deaf community. While he deeply cared for them, he did not want them to live in isolated deaf communities. His goal was for them to integrate and do everything that hearing people could.

7. He Used Visible Speech to Teach a Dog to Speak

How skilled a teacher was Alexander Graham Bell? He mastered Visible Speech so thoroughly that he was able to teach dogs to communicate.

At the age of 20, Bell adopted a stray terrier named Trouve and applied his father’s methods to teach the dog to speak. Bell manipulated the dog’s mouth to create the sound “ma” and trained Trouve to say “mama” whenever it begged for a treat.

Bell didn't stop at the basics. He quickly moved on to more complex sounds like 'ah,' 'ow,' 'oo,' and 'ga.' Then, he combined them and managed to get the dog to say something that sounded like 'How are you, Grandmama?' even though it came out as 'ah ow oo ga ma ma.'

To get that phrase, Bell had to assist the dog, adjusting its lips. Despite the impressive feats, Bell felt let down because the terrier never quite reached the level where it could be part of polite society. Nonetheless, Bell proved his methods could teach even deaf individuals how to speak.

6. He Played a Key Role in Helen Keller's Ability to Speak

Though Bell doesn't always receive the recognition he deserves, it was his work that enabled Helen Keller to speak. When she was young, her parents sought Bell's expertise. He was renowned as one of the world's best educators for the deaf.

When Bell met Keller for the first time, he made his pocket watch ring, allowing her to feel its vibrations. This moment stayed with her forever. She later described Bell as 'the door through which I should pass from darkness into light.'

Bell connected Keller's parents with the Perkins Institute, which sent Anne Sullivan, the teacher who would later become known as 'the miracle worker.' Sullivan famously taught Keller to say 'water,' a milestone that she eagerly shared with Bell.

He spread the word of Keller’s progress and turned her into a public figure. Bell regularly sent money to help with her expenses and even learned how to use a braille typewriter to correspond with her. In gratitude, Keller dedicated her autobiography to him.

5. He Served as President of the International Eugenics Congress

Even after marrying a deaf woman and meeting Helen Keller, Bell remained steadfast in his beliefs about deaf eugenics. He continued to argue that deaf individuals should be discouraged from marrying others with the same condition.

Eugenics was a central aspect of Bell’s life. He became the leader of the Eugenics Section of the American Breeders Association and was named honorary president of the Second International Eugenics Congress.

At the time, many eugenicists advocated for the sterilization of deaf individuals. Leonard Darwin, the keynote speaker at the congress, called for 'the elimination of the unfit' and supported the use of X-rays for sterilizing the mentally impaired.

Today, Bell is often linked to these controversial ideas. However, it's important to note that he only endorsed selective breeding, not sterilization. Still, he wasn’t entirely innocent—he publicly advocated for the exclusion of 'undesirable ethnical elements' from immigrating to the US to allow the development of 'higher and nobler' Americans.

Helen Keller, influenced by her teacher’s views, took them even further. Despite her own condition, she once wrote a letter advocating for the euthanasia of disabled children and described eugenics as a 'weeding of the human garden that shows a sincere love of true life.'

4. He Created the Telephone to Satisfy His Deaf Fiancée

If the deaf people in Bell's life had been excluded, he might never have invented the telephone. His interest in acoustics was sparked by his mother, who would have him speak near her forehead in a low voice so she could feel the vibrations. This experience ignited the idea that led to his groundbreaking invention.

In his early twenties, Bell began working with the phonautograph, one of the first sound recorders. His primary goal was to understand how sound could assist the deaf. He used it to demonstrate the flaws that cause hearing loss. Eventually, he realized these concepts could be applied to sound transmission, although his focus remained on helping the deaf.

It was Bell's deaf fiancée, Mabel, who insisted he dedicate himself to the telephone. Her father had financially supported Bell’s research, but Bell kept redirecting his attention to work with the deaf. Mabel wrote him a letter threatening to end their engagement unless he abandoned his Visible Speech project, stating, 'You should not have me unless you give up [Visible Speech].'

3. His Final Words Were in Sign Language

Despite his opposition to it, Bell learned sign language. And in his final moments, his last words were communicated through signs.

Those final words were for his beloved wife, whom he adored, as evidenced by the heartfelt love letters he left behind. On the night they became engaged, he penned a note that read: 'I am afraid to fall asleep, lest I should find it all a dream—so I shall lie awake and think of you.'

While traveling, Bell wrote a letter revealing the depth of his longing for her. He described a vivid vision he had while lying alone in bed: 'I felt a hand placed lightly on my shoulder—and a soft cheek was laid on my cheek—and a voice said, “How do you do, little boy!!!” Fancy my surprise—for the voice, Mabel—was your voice!!' he wrote. 'I turned over immediately to offer you a hug—and found no one there!'

On his deathbed, she too feared the thought of living without him. Grasping his hand, she begged, 'Don’t leave me.'

Bell lacked the strength to speak. He signed the word 'no,' but that was the last word he could muster. He passed away, with his final word being signed in the very language he had worked so hard to eliminate.

2. He Played a Role in the Ban of Sign Language

Bell despised sign language more than anything else. He believed it was as foreign to English as German, and that it isolated deaf people from the rest of society. He advocated for its prohibition.

In 1880, riding on the fame he gained from inventing the telephone, Bell attended the International Congress of Educators of the Deaf. There, he proposed a bill to prohibit the use of sign language in schools.

At that time, Bell was the most powerful figure at the congress. He used his influence to prevent deaf educators from voting. With their voices silenced, his bill passed, leading to a global ban on sign language and deaf teachers in schools.

In Bell's view, his triumph over sign language was more significant than inventing the telephone. He had fought against it and emerged victorious. However, for many in the deaf community, this would become a sorrowful chapter. Literacy rates for the deaf would plummet, and Bell’s policies would remain in place for a century, leaving a lasting animosity toward him within a significant portion of the deaf population.

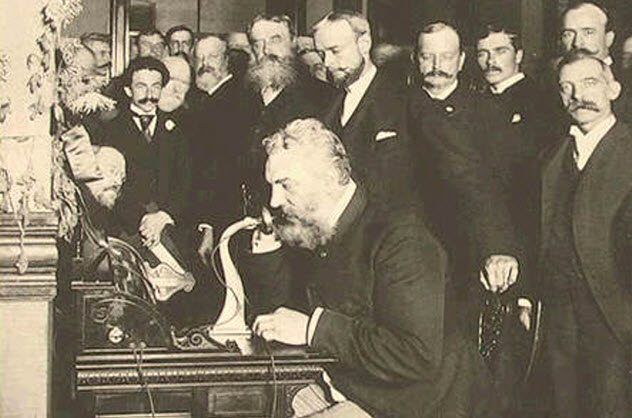

1. He Almost Missed the Telephone’s Debut to Teach Deaf Children

Alexander Graham Bell became a household name when he introduced the telephone at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. It was the world’s first look at his groundbreaking invention, earning him a gold medal and international fame.

Yet, he nearly skipped the event. Bell had a class scheduled for the same day and believed that teaching deaf children was more important than showcasing the telephone. It was Mabel who urged him to attend, threatening, 'If you won’t do a little thing like this now, I won’t marry you.'

Bell attended the event, later telling his mother that he only went because he couldn’t refuse Mabel. However, during the trip, he wrote letters to his fiancée, expressing frustration over the obligation she had imposed on him.

'Oh! My poor classes!' he lamented in one letter. 'I will be far happier and more honored to send out a group of skilled teachers for the deaf and dumb who will accomplish meaningful work than to receive all the telegraphic honors in the world.'

Despite giving in to Mabel’s request, Bell hadn't abandoned his commitment to his work with the deaf. The telephone wasn’t his only exhibit; he had also created a pavilion showcasing Visible Speech. On the day he introduced the telephone, Bell was actually more pleased with the lesser-known gold medal he won for his contributions to deaf education.