For a long time, surgery was a perilous endeavor, with many patients dying from infections believed to be caused by 'bad air.' However, in the 19th century, British physician Joseph Lister (1827-1912) changed the course of medical history by discovering the true cause of infections and finding ways to prevent them.

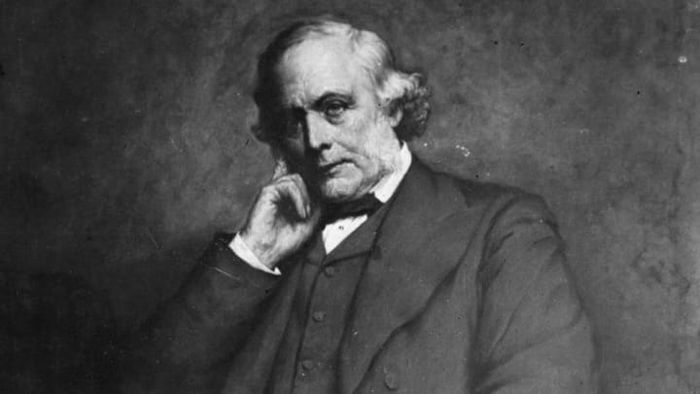

Meet the reserved and thoughtful physician often credited as 'the father of modern surgery,' a man whose legacy extends to both a towering mountain and a widely known mouthwash brand.

1. Joseph Lister's father played a key role in the advancement of the modern microscope, paving the way for his son's groundbreaking career in medicine.

As a child, Lister’s passion for science was nurtured by his father, Joseph Jackson Lister, an English wine merchant and amateur scientist. The elder Lister’s experiments with early microscopes contributed to the creation of today’s modern achromatic (non-color-distorting) microscope, a groundbreaking achievement that earned him a place in the Royal Society, the world's oldest national scientific institution.

In addition to dissecting small animals, reconstructing their skeletons, and drawing their remains, the young Lister—who was determined to become a surgeon from an early age—spent much of his childhood using his father’s microscopes to explore various specimens. Throughout his scientific career, he relied on microscopes to study the action of muscles in the skin and eye, blood coagulation, and how blood vessels reacted in the early stages of infection.

2. Though Joseph Lister was English by birth, he spent much of his professional life in Scotland.

Lister was born in the village of Upton, Essex, England, and studied at University College, London. After graduating and working as a house surgeon at University College Hospital—where he was inducted as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons—he moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, to serve as the assistant to the renowned surgeon James Syme at the Royal Infirmary [PDF].

What was meant to be a temporary move turned into a lasting success for Lister, both professionally and personally. He married Syme’s daughter, Agnes, and was later appointed Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow.

3. Joseph Lister once considered a life in the clergy instead of medicine.

Like many young individuals at a crossroads, Lister experienced moments of doubt about his career. Raised in a devout Quaker family, he briefly entertained the idea of becoming a priest rather than a surgeon. However, his father urged him to remain in medicine, suggesting that he could serve God by healing the sick. Ultimately, Lister chose a different path, leaving the Quaker faith to marry Agnes Syme, a member of the Scottish Episcopal Church.

4. Joseph Lister battled depression during his early life.

During his school years, Lister contracted a mild case of smallpox. While he recovered, the illness—coupled with the death of his older brother from a brain tumor—led him into a profound depression. He eventually left his studies in London, spending time traveling across Britain and Europe before returning to university with a renewed commitment to his medical education.

5. Joseph Lister is the reason we now sterilize wounds.

In Lister's time as a surgeon, blood-soaked sheets and surgical coats were rarely cleaned, and medical instruments were almost never disinfected. Although Italian physician Fracastoro of Verona had speculated in 1546 that tiny germs might cause contagious diseases, few connected this idea to wound infections. Instead, most surgeons believed that 'bad air'—or miasmas—was the culprit, emanating from the wounds themselves.

However, Lister trusted his own observations. As a young medical student, he observed that some wounds healed better when cleaned and when damaged tissue was removed. Despite this, infections remained a persistent issue throughout his career until he encountered the research of French scientist Louis Pasteur, who proved that microbes were responsible for infections.

Intrigued by Pasteur’s discoveries, Lister began experimenting with a solution of diluted carbolic acid—a byproduct of coal tar used to kill parasites in sewage—to sterilize surgical tools and wash his hands. He also applied the solution to bandages and sprayed it in operating rooms, where high death rates had previously been common. In 1867, he reported the results to the British Medical Association: 'My wards […] have completely changed their character, so that during the last nine months not a single instance of [blood poisoning], hospital gangrene, or erysipelas has occurred in them.'

While some doctors criticized Lister’s methods, claiming they were inefficient and costly, his approach soon gained traction. Before long, doctors in Germany, the U.S., France, and Britain were adopting his techniques. Lister and Pasteur corresponded, and in 1878, they finally met in person. At Pasteur's 70th birthday in 1892, Lister delivered a moving speech lauding the life-saving significance of Pasteur's research.

6. Lister was known for his compassion and kindness towards his patients.

Lister preferred to refer to his patients with respect, calling them 'this poor man' or 'this good woman' rather than 'cases,' and he made every effort to keep them calm and comfortable before and after surgery. On one occasion, he even repaired a doll’s missing leg for a young patient under his care.

7. He treated Queen Victoria ...

One of Lister’s most famous patients was Queen Victoria. In 1871, the surgeon was summoned to the queen's Scottish estate when she developed an abscess the size of an orange under her armpit. Armed with carbolic acid, Lister drained the pus, dressed the wound to prevent infection, and performed the surgery. However, in the process, he accidentally sprayed the queen’s face with the disinfectant, much to her displeasure.

Lister later humorously told his medical students, 'Gentlemen, I am the only man who has ever stuck a knife into the queen!''

8. ... who later made him a baron.

As Lister's reputation soared, Queen Victoria honored him with a baronetcy in 1883, later elevating him to baron status. Lister remained highly respected by the royal family, including Edward VII, who was diagnosed with appendicitis just two days before his 1902 coronation. The king's doctors consulted Lister before successfully performing the surgery, and upon being crowned, Edward made sure to thank him. 'I know that if it had not been for you and your work, I wouldn’t be sitting here today,' the monarch told Lister.

9. The popular Listerine mouthwash is named after Joseph Lister.

Even if you didn’t study Lister in science class, you've likely used something named after him: Listerine. This well-known mouthwash, advertised with the slogan 'Kills germs that cause bad breath,' was first invented in 1879 by American doctor Joseph Lawrence. Initially created as an alcohol-based surgical antiseptic, Lawrence chose to honor Lister by naming the product after him. Despite its origins, Listerine was later marketed for oral hygiene, though it was once sold as a treatment for colds, dandruff, and even a cigarette additive.

10. Lister also has a mountain named in his honor.

Lister is commemorated with public monuments and hospitals around the world. However, if you visit Antarctica, you’ll find Mount Lister, the highest peak in the Royal Society Range in Victoria Land. This impressive mountain, standing at about 13,200 feet, was named after Lister because of his role as the Royal Society's president from 1895 to 1900. The Royal Society and Royal Geographical Society organized the British Discovery Expedition of 1901-1904, which first explored the region, and chose to name the peak in his honor.

Further Reading: The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister's Journey to Revolutionize the Bloodstained World of Victorian Medicine by Lindsey Fitzharris