The medieval era was dominated by beliefs in witches, goblins, and shadowy spirits. These supernatural entities were thought to have been eradicated during the Enlightenment, as scientific progress flourished and religious authorities rejected superstitions. However, despite the rise of empirical methods and the advancement of human knowledge, these ancient beliefs endured, evolved, and adapted over time.

10. Blood-Stopping

In the Ozarks region, spanning Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas, there exists a tradition of “power doctors” believed to heal illnesses through supernatural methods. Among their most renowned practices is blood-stopping, a magical technique used to halt excessive bleeding. This often involves reciting a verse from the Book of Ezekiel: “And when I passed by thee, and saw thee polluted in thine own blood, I said unto thee when thou wast in thy blood, Live; yea, I said unto thee when thou wast in thy blood, Live.” In the 1960s, a Georgian woman claimed she could perform blood-stopping over the phone by replacing “thee” with the patient’s name. A simpler version used by a Missouri blood-stopper involved the phrase: “Upon Christ’s grave three roses bloom, Stop, blood, stop!”

Certain blood-stoppers have asserted their ability to extend their influence to farm animals and, in one remarkable instance, even to a piece of meat. A skeptic dining with a self-proclaimed blood-stopper once challenged him, saying, “Let’s see you try your luck on this beef.” The blood-stopper warned, “Alright, but it’ll ruin your beef.” As the story goes, the skeptic went without dinner that night. “They slaughtered it and stuck it. It never bled a drop. The blood remained trapped in the flesh, spoiling it completely. It was inedible.”

Fascinatingly, a similar practice was found among the Saami people of northern Norway, which later influenced non-Saami folk magic practitioners and continued into modern times. Much like in the Ozarks, religious invocations were frequently employed to stop bleeding, often invoking the Trinity:

Stop blood! As the water stopped In the river of Jordan In the three holy names God the Father and Son And the Holy Spirit.

9. Concealed Items

Between 1788 and 1868, 160,023 convicts were transported to Australia, yet very little remains of the clothing they wore. This peculiar detail is likely tied to the secretive folk magic practice of concealing items. In the strange and unfamiliar environment they were forced into, convicts relied on superstitions to shield themselves from malevolent supernatural forces. They turned to an ancient British magical custom—hiding clothing, shoes, toys, trinkets, and even dead cats within houses and buildings to safeguard the inhabitants from evil spirits.

In 1980, workers renovating Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks uncovered two convict shirts hidden within the building’s structure, and many similar discoveries have followed. One of the most intriguing finds was a child’s shoe concealed in a pylon of the Sydney Harbor Bridge. Australian historian Ian Evans noted that it was “placed there by a builder or stonemason to ward off evil forces.”

No written records exist of this clandestine practice, and it has only come to light through the discovery of old boots, shoes, worn-out clothing, children’s toys, and the remains of dead cats hidden in the walls of colonial-era homes. These items were typically concealed in obscure areas of the house, such as behind walls, inside chimneys, or in attic crawl spaces—spots believed to be vulnerable entry points for malevolent entities.

This tradition is thought to have persisted in parts of Australia until at least the 1930s, with thousands of such protective items still hidden in homes, unbeknownst to their occupants. One clue to their presence is the existence of evil-averting marks or apotropaic symbols, mystical carvings found near windows, doors, fireplace lintels, or in roof cavities.

8. Fishers’ Magic

For centuries, seafarers isolated from society have upheld various superstitions and rituals to safeguard their voyages, traditions that continue today. In Gloucester, Massachusetts, during the 1800s, fishermen were wary of so-called 'Jonahs'—people, ships, or items believed to bring misfortune. A series of unsuccessful hauls could brand someone as a Jonah, potentially resulting in their expulsion from the crew. To identify a Jonah, the ship's cook might conceal a nail, wood fragment, or coal in bread; the recipient was deemed unlucky unless proven a skilled angler.

Certain actions were also considered Jonahs, though opinions varied widely on what constituted bad luck. These included crafting model ships at sea, anchoring in an unlucky manner, or cleaning the deck improperly while fishing. Some viewed soaking mackerel in a bucket as particularly unlucky, as it was thought to prevent a bountiful catch.

Gloucester's fishermen adhered to numerous peculiar beliefs, such as whistling against the wind or inserting a knife into the mast's aft side to call for wind. Earrings were worn by some to enhance vision, while others carried charms like fish bones or horse chestnuts for luck. Potatoes in pockets were believed to ward off rheumatism, and nutmeg necklaces were thought to cure scrofula.

A unique tradition in Cape Cod involved the dressing of fish. The header would remove the fish's head and pass the body to the splitter. If the fish still moved, the splitter would request the header to kill it by hitting the severed head. A Gloucester captain noted, 'It's strange but true that striking the head causes the body to stiffen.'

7. Kaji Kito

During Japan's late Edo period, the popularity of folk religion grew significantly, with many visiting temples and shrines focused on kaji kito, or 'magical intercession.' The upper class disapproved of this trend, labeling it as inshi jakyo ('immoral and deviant religion'). Nakai Chikuzan, an 18th-century Confucian scholar, was especially vocal in his criticism.

Predicting fortunes, offering healing prayers, advising on auspicious directions for doctors, or discouraging medicine use, sometimes fatally; exploiting the worship of Ebisu and Daikoku for immoral acts, using Tenmangu shrines for indecent purposes, replacing midwives with Kannon; spreading tales of badgers, foxes, and tengu, attributing miracles to minor deities and buddhas; interpreting dreams of gods and buddhas, selling fake remedies, conducting compatibility, physiognomy, sword, and house geomancy divinations—these deceptive practices mislead the uneducated masses.

However, these temples fulfilled a need as urbanization drew people away from their rural roots and traditional customs. Kitoji ('intercession temples') catered to city dwellers by offering religious and magical services. A well-known 1814 guide, Edo Shinbutsu Gankake Chohoki (A Treasury of Invocations to Deities and Buddhas in Edo), listed local shrines and temples along with their unique magical offerings—relieving toothaches or headaches, curing smallpox, warding off thieves or snakes, fostering marital harmony, and safeguarding infants' scalps.

Religious institutions faced growing pressure to cater to their followers, leading to the organization of kaicho festivals. During these events, sacred statues and artifacts were exhibited, and offerings were collected. The Edo Hanjoki, written in 1832, documented these gatherings:

Deities and buddhas travel great distances from all corners to converge in Edo. It's unclear whether they bring luck to the people or if the people bring prosperity to them. [ . . . ] Crowds swarm the streets like ants to rice bran, their sweat falling like rain. At the destination, a temporary structure is erected, adorned with curtains and lavish decorations, where miracles are marketed.

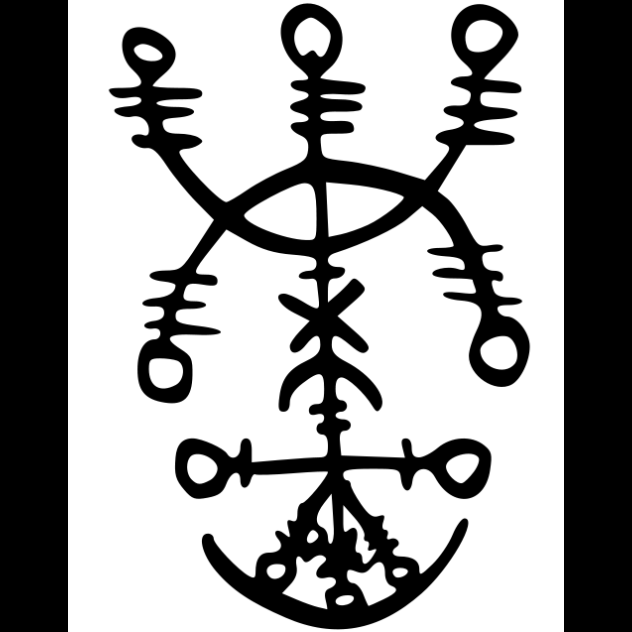

6. Galdrastafir

Rooted in medieval mystical and pagan traditions, galdrastafir are Icelandic magical symbols intended to manipulate or influence the world. These sigils blend Norse runes and pagan mythology with Judeo-Christian influences. While they may have originated in the 1400s, their popularity surged in the 17th century, with most surviving grimoires from that era. Practitioners, known as galdramenn, were educated in Scandinavia and Germany, initially training for the clergy but returning as magicians. Their literacy allowed them to captivate the largely illiterate populace with their enchanting skills.

Galdrastafir come in various forms. The oldest, asymmetrical types, feature intersecting lines or small shapes with cryptic meanings. Symmetrical versions resemble cartwheels or snowflakes, often merging Christian and runic symbols. Runic galdrastafir consist of rune sequences with obscure meanings, while seal or insignia types mimic European occult seals, referencing Christian leaders, kings, and angels. The most intricate are the superstaves, or 'rood-cross,' primarily used for warding off evil.

While some galdrastafir were for general luck or protection, others served specific purposes. Many aimed to influence human relationships, such as one claiming, “A girl will love you. Carve this stave into your palm with saliva and shake her hand.” Others were designed to aid in economic endeavors, legal disputes, weather control, or even games and wrestling. A few malicious spells exist, though relatively harmless, like causing uncontrollable flatulence, vomiting, or falling off a horse. The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft offers an online guide detailing various galdrastafir and their uses.

5. Witch Smellers And War Diviners

Among the Nguni communities of South Africa's Cape region, including the Zulu and Xhosa, healer-diviners, collectively called amagqira or izangoma, held significant roles. These included izanuse ('omniscient diviners'), amaxhweli ('herbalists'), nolugxana ('medicine digging-stick doctors'), awemilozi ('ventriloquists'), ambululayo ('revealers'), awomhlahlo ('appeal diviners'), awamathambo ('bone diviners'), aqubulayo ('extractors'), awezipili ('mirror diviners'), and awemvula ('rainmakers').

A notable magical figure in Nguni societies was the igqirha elinukayo ('witch smellers'), tasked with identifying witches and those employing dark magic against rivals. They also served as spirit mediums and were sought for supernatural assistance during illness or calamity. Christian missionaries criticized their practices, labeling their spiritualism as 'jugglery and incantations' and criticizing their healing methods: 'They often endanger lives by administering excessive drugs without monitoring their effects.'

Zulu king Shaka, wary of the witch smellers' influence, viewed them as a challenge to his authority. To counter this, he centralized their role, claiming his army was immune to witchcraft accusations and adopting the title 'Dream Doctor' to establish his spiritual dominance over them.

In the Frontier Wars (1846–1878) between the English and the Xhosa, war diviners (amatola or itola) were pivotal. War herbalists prepared a mixture from the umabophe plant ('to tie up') and applied it to warriors for invincibility or to calm rivers for safe crossing. They also made skin incisions and rubbed in animal fat to instill bravery. Post-war, most diviners reverted to being herbalists, and war divination faded into history.

4. Cunning Folk

The term 'cunning folk' in England described individuals who practiced beneficial magic, such as healing, curse removal, identifying wrongdoers, and fostering love. These practices originated in the Dark Ages, with the term deriving from the Anglo-Saxon word cunnan, meaning 'to know.' Their popularity surged after the Reformation, as they assumed roles of healing and supernatural protection previously held by Catholic clergy.

During this era, a distinction emerged between harmful black magic and helpful white magic, though both were condemned by mainstream religion. Despite public demand for their services, cunning folk lived on society's margins, facing constant persecution. Some were tried under witchcraft laws, while others were summoned by church authorities and accused of promoting superstitions the Church of England sought to eliminate.

Wealthier cunning folk had access to advanced magical arts like astrology, alchemy, and necromancy, while those from lower classes relied on basic literacy and occult knowledge. Many practiced not for profit but to enhance their community standing. Magical knowledge was often inherited, taught by masters, or learned by observing other cunning folk.

Cunning folk offered a wide range of services, employing various incantations, preparations, and rituals. To identify thieves, they used a method involving slips of paper with suspects' names placed in a key's hollow while holding a Bible. When the Bible 'waggled' and fell, the guilty party was revealed. Healing rituals often incorporated Catholic prayers or cryptic written charms, which seemed mystical to the largely illiterate clientele. Protective measures included 'witch-bottles' or 'bellarmines,' filled with mixtures of hair, urine, and pins, then buried or burned as a powerful counter-magic.

3. Hoodoo

Hoodoo, an African-American folk tradition also known as Conjure, differs from the religious system of voodoo (Vodou), though both trace their roots to West Africa. Hoodoo is a magico-religious practice aimed at influencing the world through spiritual forces, for both benevolent and malevolent purposes. It originated among enslaved Africans and their descendants in the southern U.S., blending traditions from regions like the Congo, Sierra Leone, and Ghana. Hoodoo also incorporated elements from Native American beliefs and European cunning folk practices.

Some argue that voodoo evolved into a structured religion by integrating Catholic saints and sacraments. In contrast, American Protestantism rejected such syncretism, leading African folk beliefs to develop covertly into hoodoo. This tradition allowed practitioners to wield esoteric knowledge without formal religious initiation. Hoodoo empowered slaves to exert control over their lives, with conjurers believed to aid escapees by misleading tracking dogs with graveyard dust or causing them to bark at trees. If recaptured, hoodoo was thought to soften slave owners' attitudes.

Rootwork, a herbal practice with West African roots, also integrated Native American knowledge of New World plants, though many African herbs were introduced by slaves. This art evolved over time; for instance, the amaranth plant, used by Native healers as an astringent, was repurposed by hoodoo practitioners to create love potions when mixed with honey and a dove’s heart. The High John the Conquer root, or bindweed, became the most revered magical root in hoodoo, despite debates over its symbolic significance. Originally a medicinal plant in Mexico, it gained prominence in hoodoo traditions.

Conjure bags, also called gris-gris bags, mojo bags, or nation sacks, were vital in hoodoo practices. Filled with roots, minerals, or animal remains, these bags connected users to the spirit world, offering love, protection, luck, and healing. A key ingredient was a bone from a black cat boiled alive, believed to grant invisibility, flight, or healing powers. Personal items like hair or nails targeted specific individuals, while graveyard dirt was used to harness the power of the dead.

2. Granny Women

In the 19th-century Appalachians, trained doctors were scarce, so locals relied on 'granny women' or 'yarb doctors,' who blended folk medicine with magic. These herbalists gathered and prepared natural remedies to ease illness symptoms. While they couldn’t cure diseases, their treatments often saved lives by mitigating severe symptoms.

Granny women were indispensable as midwives in the Appalachian region. With doctors often too distant to assist during childbirth, these women provided immediate and prolonged care. They offered emotional comfort, supported by mystical rituals believed to ensure a safe delivery. A laboring woman would hold her husband’s hat, symbolically including him in the process, while an axe or knife under the bed was thought to 'cut' the pain. Doors and windows were opened to symbolize the birth canal’s dilation.

Herbal remedies played a key role in easing childbirth. Raspberry tea relaxed uterine muscles, blackberry prevented hemorrhaging, and slippery elm bark tea hastened delivery. In dire situations, mothers were given laudanum, morphine, or quinine, as these drugs were readily available before 1906.

1. Powwowing

Powwowing, rooted in older traditions and introduced by German settlers, is a religious and magical practice among the Pennsylvania Dutch, especially the Amish, Dunkers, and Mennonites. This tradition, known as brauche in German, likely stems from pre-Reformation practices tolerated by the Catholic Church but later suppressed by Protestants. Powwowing served protective and healing purposes, such as neutralizing hexes or curing ailments, though failures were often attributed to the patient’s lack of faith.

Powwowing rituals often draw from biblical passages, with specific verses believed to hold supernatural power, such as Ezekiel 16:6, also used by Ozark blood-stoppers. Many incantations invoke saints, and some powwowwers, like German immigrant Anna Maria Jung, gained saint-like reverence. After her husband’s death in the American Revolution, she became known as 'Mountain Mary' or 'Barricke Mariche' among locals.

Another key source of powwowing incantations is John George Hohman’s 1819 work, Der lang verborgene Schatz und Haus Freund (The Long Lost Friend). This book includes powerful spells from the Bible, occult texts like Romanusbuchlein, and Egyptian Secrets, attributed to 13th-century monk Albertus Magnus. Hohman claimed the book itself was a protective charm and offered practical spells, such as:

A GOOD REMEDY FOR THOSE WHO CANNOT KEEP THEIR WATER—Burn a hog’s bladder to powder and take it inwardly.

A GOOD REMEDY TO STOP BLEEDING—This is the day on which the injury happened. Blood, thou must stop, until the Virgin Mary bring forth another son. Repeat these words three times.

TO EXTINGUISH FIRE WITHOUT WATER—Write these words on each side of a plate, and throw it into the fire and it will extinguish forthwith:

SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS

A more perilous text in powwowing is the enigmatic The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, reputed to include spells for black magic and spirit summoning. Powwowers typically reject any association with black magic or hexerei. As 19th-century powwower Peter Bausher stated: 'My sole aim is to heal the sick and aid the suffering. Heaven knows the world has enough pain.'