In 1908, Harvard released the Revised Harvard Photometry Catalog, which defined 88 constellations later recognized globally by astronomers. This led to obscure star clusters like the Microscope, Swordfish, and Compass (the drawing tool) gaining equal standing with iconic constellations such as Orion and Cassiopeia. If those sound unusual, here are 10 more that were ultimately left out.

1. Globus Aerostaticus, the Hot Air Balloon

Planetario.Gov

In 1798, French astronomer Jérôme Lalande introduced the Balloon constellation to honor the advancements in transportation technology. While balloons were a groundbreaking invention at the time, the constellation's popularity faded as quickly as Falcon Heene's fleeting fame.

Can you spot it? The Balloon once occupied the celestial region between Capricorn and the Southern Fish.

2. Machina Electrica, the Electric Generator

Astrobob

With Greek mythological figures exhausted, many constellations, including some still recognized today, were named after contemporary inventions. Thus, a dull section of the sky was designated as the Electric Generator. Unfortunately, it failed to captivate astronomers and was eventually discarded—a choice that might feel shortsighted during the next major power outage.

Can you locate it? Machina Electrica was positioned between the Furnace and the Sculptor’s Studio, making that part of the sky resemble a cluttered attic.

3. Cancer Minor, the Smaller Crab

j.dreuille.free.fr

Many constellations have smaller versions. Whether you spot Bears or Dippers in the northern sky, it’s clear there’s a larger and a smaller version. Similarly, there’s a Major and Minor Dog (the latter being so insignificant it consists of just two stars). There’s even a minor counterpart to Leo, which might explain why Cancer Minor was proposed. However, the Little Crab never gained traction, which is likely a good thing—otherwise, we might have ended up with Virgo Minor.

Can you spot it? It’s a tiny, arrow-shaped cluster to the left of Cancer, pointing directly at it.

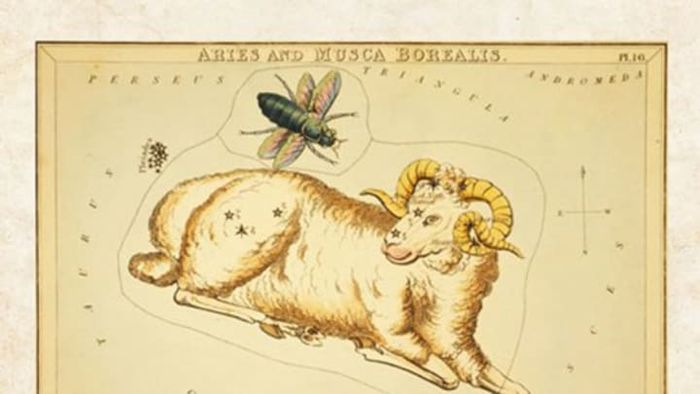

4. Musca Borealis, the Northern Fly

Fulcrumgallery.com

As explorers ventured south and mapped the southern skies, they discovered vast uncharted regions with limited naming inspiration. This led to the creation of 'southern' constellations, with duplicates like fish, crowns, and triangles. However, the night sky didn’t need two flies, and despite rebranding attempts such as Apis (the Bee) and Vespa (the Wasp), this tiny insect couldn’t escape fading into obscurity.

Meanwhile, its southern counterpart, Musca (formerly Australis), continues to buzz near the southern celestial pole to this day.

Can you spot it? The Northern Fly was initially observed near the hindquarters of Aries, the Ram—an oddly fitting location.

5. Polophylax, the Protector of the Pole

Ianridpath.com

The South Pole often gets overlooked. Unlike the North Pole, which boasts the iconic North Star, the southern skies are a lackluster collection of faint stars. In 1592, Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius tried to add some allure by introducing Polophylax, a blue-robed guardian of the celestial South Pole. Unfortunately, this idea fell flat and was eventually replaced by constellations like the Toucan and the Crane—ironically, also proposed by Plancius.

Can you locate it? Follow your instincts. (Sorry, couldn’t resist the Toucan pun.)

6. Limax, the Slug

While some of Plancius’s constellations survived, John Hill, a rebellious botanist and notorious mischief-maker, holds the record for quirky constellation ideas—and a complete lack of success. In 1754, Hill published his star guide Urania (a title as wordy as Fiona Apple’s album names), filling the sky with Limax (the 'naked snail'), an Earthworm, a Rhinoceros Beetle, an Anteater, a Toad, and nearly every other slimy creature imaginable, horrifying younger siblings everywhere. None of his creations lasted.

Can you spot it? Limax once crawled beneath the left foot of the mighty Orion.

7. Gladii Electorales Saxonici, the Crossed Swords of Saxony

zwoje-scrolls.com

This constellation was the brainchild of German astronomer and shoemaker Gottfried Kirch, who also invented other forgotten symbols like orbs and scepters to flatter German nobility—a celestial attempt at flattery that failed. Still, it’s surprising no heavy metal band has adopted this name yet.

Can you locate it? It’s positioned almost directly between Virgo and Libra—great news for late September birthdays seeking a unique zodiac alternative.

8. Psalterium Georgii, the Harp of King George III

j.dreuille.free.fr

Flattering royalty with ill-fated constellations is a sadly persistent trend (see Frederici’s Regalia, Herchel’s Telescope, Pontianowski’s Bull, and the Bust of Christopher Columbus). Fortunately, it’s now simpler to spend $75 to name a star after someone—a gesture just as unofficial as Psalterium Georgii turned out to be.

Can you spot it? Today, King George’s Harp drifts in the northern reaches of the River Eridanus, alongside a few beer cans and an old tire.

9. Sciurus Volans, the Flying Squirrel

Astrocultura.uai.it

“Hey, Rocky! Watch me pull a forgotten constellation out of my hat!” Since the sky already featured a different Volans (celebrating the majestic Flying Fish), this one had no tricks left to succeed.

Can you spot it? If you manage to locate the elusive Camelopardalis (the Giraffe) in the northern sky, just glance toward its tail. And yes, the night sky is likely the only place where spotting a giraffe is a challenge.

10. Officina Typographica, the Printing Press

ianridpath.com

Not just a printing press, but an entire office. If your desk is any indication, you’d need a galaxy’s worth of stars to depict the chaos. Failing to inspire anyone, the printing office was phased out, its celestial space now claimed by a unicorn.

Similar to the electrical generator (and a host of other inventions), this faint, formless homage to modern innovation was conceived by German astronomer Johann Bode. But don’t pity him—his naming success with planets, particularly Uranus, more than made up for his constellation flops.

Can you spot it? It was located just east of Sirius, the night sky’s brightest star—a hard act to follow.