Throughout history, rivers have been concealed due to issues like pollution, disease, urban expansion, or a combination of these factors. From city planners to engineers, efforts to divert waterways underground have persisted as recently as three decades ago. Meanwhile, literature, poetry, and cinema keep the memory of these vanished rivers alive. Indicators of an underground river might include lush greenery, winding roads, or faint sounds of flowing water.

While the primary reason for burying a river often revolved around progress, contemporary cities are now exploring the idea of “daylighting” these waterways. Many urban areas are debating the feasibility of restoring their rivers, with some already successfully reviving these hidden treasures.

1. Neglinnaya, Moscow, Russia // Concealed by 1812

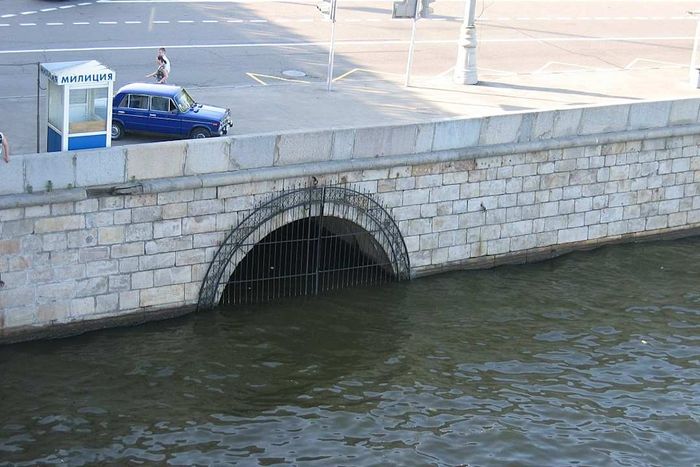

The outflow of the Neglinnaya in Moscow. | Alexander Savin, Wikimedia Commons // Free Art License 1.3

The outflow of the Neglinnaya in Moscow. | Alexander Savin, Wikimedia Commons // Free Art License 1.3The Neglinnaya River in Russia once meandered from northern Moscow to the south, converging with the Moskva River. This confluence created a triangular area where the iconic red-brick Kremlin fortress was established in the late 15th century (the Neglinnaya acted as a moat along the Kremlin’s eastern side).

One hypothesis about the river’s name traces it to the ancient Russian term neglinok, referring to a “marshy area.” As Moscow expanded, the Neglinnaya shrank, and industries flourished along its banks. By the mid-18th century, flooding and contamination had become significant issues. The catastrophic fire of 1812, reportedly ignited by Russians during Napoleon’s invasion, worsened the Neglinnaya’s condition, prompting engineers to enclose it.

Today, the Neglinnaya runs hidden alongside other submerged waterways, clandestine Soviet bunkers, and an abandoned underground railway rumored to have been constructed by Stalin for connecting key locations. Encased in roughly 4.7 miles of tunnels, the river discharges into the Moskva through two outlets. Adventurers can venture into this subterranean realm, provided they steer clear of the Kremlin.

2. River Farset, Belfast, UK // Concealed by 1848

The sculpture ‘The Salmon of Knowledge’ indicates the confluence of the River Farset and the Lagan. | William Murphy, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 2.0

The sculpture ‘The Salmon of Knowledge’ indicates the confluence of the River Farset and the Lagan. | William Murphy, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 2.0The River Farset, derived from the Gaelic Béal Feirste (“mouth of the sandbank”), is the namesake of Belfast. Once the lifeblood of the city’s commerce, the Farset originates from a watercress-rich field on Squire’s Hill north of Belfast, travels underground near Shankill Graveyard, runs alongside the “Peace Wall” that once divided Protestant and Catholic communities, winds its way to High Street, and eventually merges with the River Lagan after approximately miles. This junction marks the site of Belfast’s earliest settlement during the Stone Age (though the city’s royal charter wasn’t granted until 1888).

Like many European cities, Belfast’s rivers suffered during the Industrial Revolution. The Farset, which powered the city’s growth, helped Belfast become a global leader in linen production. However, industrial pollution transformed the river into a sewer, leading to its concealment by 1848.

Since 2013, supporters have been exploring the idea of uncovering a section of the Farset, potentially allowing the river to resurface.

3. Waihorotiu Stream, Auckland, New Zealand // Concealed by 1860

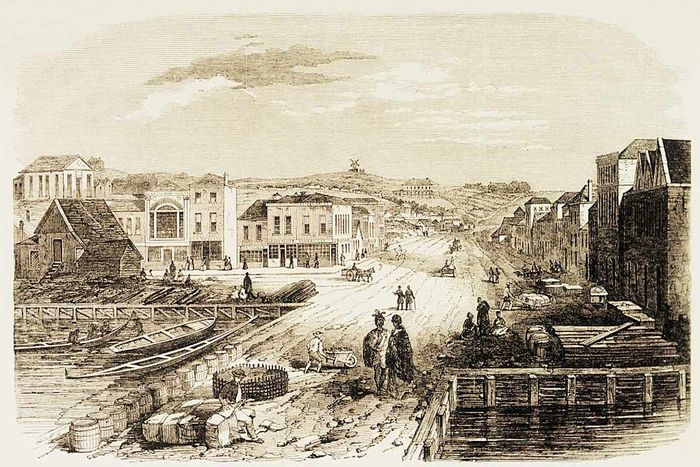

A mid-19th century depiction of Queen Street in Auckland, tracing the route of the Waihorotiu Stream. | Historical/GettyImages

A mid-19th century depiction of Queen Street in Auckland, tracing the route of the Waihorotiu Stream. | Historical/GettyImagesIn Māori legend, Waihorotiu is the dwelling place of Horotiu, a guardian spirit of nature. The Waihorotiu Stream, an ancient awa (“river”), once provided drinking water and sustenance as it flowed through what is now Queen Street in central Auckland.

Stretching roughly one mile, the Waihorotiu flows from Aotea Square (once a marshland) to the harbor. While the first recorded European explorer, Abel Tasman, reached the region in 1642, significant European migration to New Zealand began after James Cook’s 1769 voyage. Accounts from the 1840s depicted Waihorotiu as a “substantial tidal creek” teeming with eels and trout [PDF]. However, colonization in the 19th century led to contamination, as businesses discharged waste directly into the stream. As Tāmaki-Makaurau (the Māori name for the area) transformed into Auckland, Waihorotiu was enclosed. By 1860, it had officially become a sewer.

Auckland’s regional council has assessed the feasibility of uncovering the Waihorotiu, concluding that current infrastructure is inadequate, though the idea remains a possibility.

4. River Fleet, London, UK // Concealed by 1880

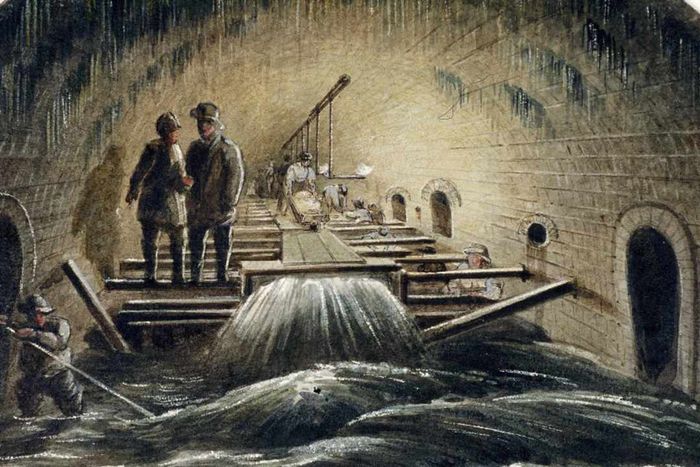

A depiction of the Fleet River in its underground section, circa 1854, by an unknown artist. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

A depiction of the Fleet River in its underground section, circa 1854, by an unknown artist. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesSpanning roughly four miles from Hampstead Heath, London’s River Fleet once created a vast tidal basin where it joined the Thames. Legend has it that Celtic Queen Boudicca led her historic revolt against Roman rule along its shores in 60 AD, and even earlier, the river supplied drinking water and powered mills [PDF]. Named after the Anglo-Saxon term flēot, meaning “tidal inlet,” it stands as the largest of London’s hidden rivers.

As London’s population expanded, so did the pollution, with tanners, butchers, and others discarding industrial waste into the river. As far back as 1290, monks petitioned King Edward I, citing that “foul odors from the Fleet” disrupted their worship. The river lent its name to Fleet Street, the renowned hub of Britain’s newspaper industry, which began in 1702.

By the 1730s, the stench became unbearable, prompting the city to enclose the Fleet. This process lasted over 140 years, and the surrounding areas turned into slums, famously depicted in Charles Dickens’s works. Cholera outbreaks further tarnished the river’s reputation, contributing to the Great Stink of 1858. The Fleet was eventually integrated into Joseph Bazalgette’s modern sewer system and fully covered by 1880.

5. Wienfluss, Vienna, Austria // Mostly Concealed by 1910

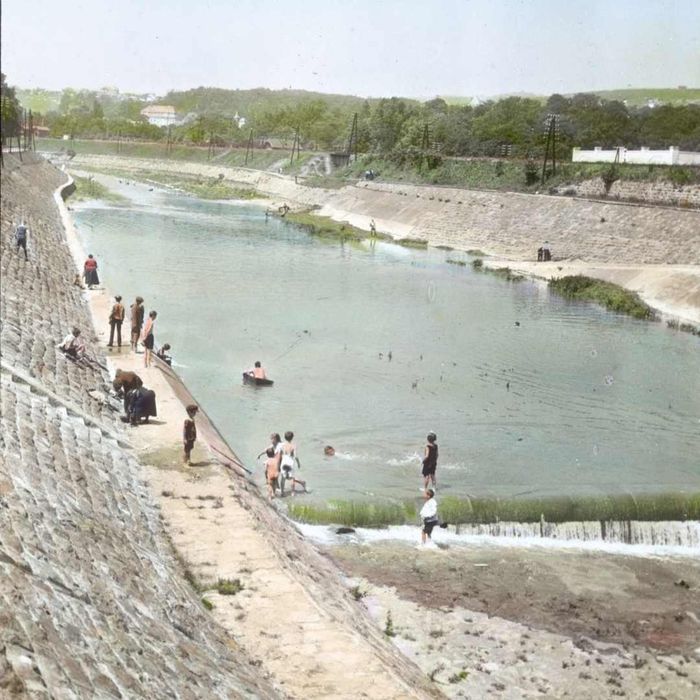

A hand-colored lantern slide from the late 19th century depicts a detention basin of the Wienfluss in Vienna. | brandstaetter images/GettyImages

A hand-colored lantern slide from the late 19th century depicts a detention basin of the Wienfluss in Vienna. | brandstaetter images/GettyImagesThe Vienna River (or Wienfluss in German) derives its name from the city, with some theories suggesting Vienna originates from the Celtic Vedunia, meaning “river in the woods.” It springs from the foot of the Kaiserbrunnberg, a wooded hill west of the city, with approximately nine of its 21 miles flowing through Vienna.

Once the Austrian capital’s primary commercial waterway, the Wienfluss transported timber until 1754 and served as a key source of hydropower alongside the Danube. However, residents and businesses frequently dumped waste into the river, leading to frequent flooding and health hazards. After a cholera epidemic in 1830, Vienna began enclosing its streams, integrating them into an extensive sewer network. By 1910, parts of the river were covered, while other sections were diverted into a canal.

More Tales About Rivers

The river still makes its presence known. Its tunnels appeared in the 1949 Orson Welles film The Third Man. Visitors can also admire the Wienflussportal, an impressive arch marking where the river resurfaces in Vienna’s Stadtpark.

6. Tibbetts Brook, Bronx, New York // Concealed by 1912

Van Cortlandt Park Lake in the Bronx, where Tibbetts Brook runs before entering the New York City sewer system. | TheTurducken, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

Van Cortlandt Park Lake in the Bronx, where Tibbetts Brook runs before entering the New York City sewer system. | TheTurducken, Flickr // CC BY 2.0New York City sits atop numerous hidden streams and springs, as illustrated by an 1865 sanitary map of Manhattan. During the 19th century, rapid urbanization leveled hills, drained marshes, and redirected many rivers underground, including Tibbetts Brook in the Bronx.

The Lenape referred to the brook as Mosholu, meaning “smooth or small stones,” and it was later renamed Tibbetts Brook after George Tippett, a 17th-century colonist. Originating in Yonkers, Tibbetts Brook travels roughly four miles before reaching Van Cortlandt Park Lake, formed in 1699 when Jacobus Van Cortlandt dammed part of the stream for his sawmill. In the early 1900s, the brook was diverted underground at Tibbett Avenue to mitigate flooding and create more usable land. However, its direct connection to New York City’s overwhelmed sewer system now causes flooding in areas along its original path.

Consequently, Tibbetts Brook is among New York’s subterranean rivers slated for daylighting. In January 2023, the city secured a portion of land required to restore Tibbetts near its original above-ground route. Expected to conclude around 2030, the project will “divert approximately 4 to 5 million gallons of water” daily from the sewer system and create new green spaces for the community, as stated in a press release from the New York City mayor’s office.

7. Bièvre River, Paris, France // Concealed in 1912

The Bièvre flows through a tunnel under Paris. | Hugo Clément, Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0

The Bièvre flows through a tunnel under Paris. | Hugo Clément, Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0While the Seine often comes to mind when thinking of Parisian rivers, the Bièvre River also once meandered through the city, even featuring in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and supplying water to Versailles’ fountains. The name’s origin is debated, possibly stemming from the Celtic beber meaning “beaver” or the Latin bibere, “to drink.”

The Bièvre originates about 22 miles southwest of Paris. Initially, it joined the Seine near the Jardin des Plantes in the 5th arrondissement. As early as the 1300s, Parliament prohibited butchers from discarding waste into the Seine but permitted it in the Bièvre, turning it into a foul cesspool. During the Industrial Revolution, industries such as tanning and dyeing transformed the Bièvre into an open sewer.

The river within Paris was enclosed in 1912 and no longer flows beneath the streets, having been rerouted approximately 13 miles outside the city. Today, passionate Parisians and environmental activists are striving to restore the Bièvre: suburban sections have been uncovered, and a segment in Paris near Parc Kellerman has been chosen for renewal, with hopes it will aid the city in addressing climate change impacts.

8. Cheonggyecheon, Seoul, South Korea // Concealed by 1958

Visitors explore Cheonggyecheon in central Seoul. | SOPA Images/GettyImages

Visitors explore Cheonggyecheon in central Seoul. | SOPA Images/GettyImagesSeoul’s Cheonggyecheon River stands as a triumph in daylighting efforts. Originally called Gaecheon (“open stream”), it was renamed Cheonggyecheon during Japanese occupation starting in 1910. Post-Korean War, rapid urbanization and overcrowded neighborhoods led to severe pollution in and around the stream. In 1958, the city encased the river in concrete, and by 1976, an elevated highway was constructed above it.

As urban planning shifted toward environmental sustainability, Seoul’s mayor initiated a project in 2003 to restore the Cheonggyecheon. The concrete covering was dismantled, the water flow reinstated, and approximately 3.6 miles of the nearly seven-mile river were brought back to the surface.

The restoration of Cheonggyecheon has led to a 15.1 and 3.3 percent increase in bus and subway usage, respectively, reducing air pollution and traffic congestion. It has revitalized neglected neighborhoods and boosted property values. Today, it functions as a flood control channel and attracts around 64,000 visitors daily. Cities worldwide view this project as a model for their own daylighting initiatives.

9. Shibuya River, Tokyo, Japan // Concealed by 1964

The Shibuya River flows hidden beneath the renowned Shibuya Scramble crossing. | Keith Tsuji/GettyImages

The Shibuya River flows hidden beneath the renowned Shibuya Scramble crossing. | Keith Tsuji/GettyImagesOriginally named Edo, meaning “coastal waters” or “estuary,” Tokyo once mirrored Venice. With an advanced water management system spanning over 100 rivers and canals, Tokyo surpassed London in population by the 1700s. Merchants transported goods via these waterways, shaping the vibrant cityscape captured in ukiyo-e woodblock prints (meaning “floating world”).

The catastrophic Great Kanto earthquake of 1923, followed by Allied bombings in World War II, devastated much of Tokyo’s wooden infrastructure. In the wake of these tragedies, the city prioritized rebuilding over its waterways. Many rivers were buried ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

A notable case is the convergence of the Onden and Uda rivers, forming the 1.5-mile Shibuya River. By the 1960s, the Shibuya had become a polluted, neglected stream, and Olympic planners opted to construct roads and railways directly over it. Today, it flows beneath the feet of countless pedestrians crossing the iconic Shibuya Scramble. Ironically, the 2020 Tokyo Olympics reignited discussions about uncovering the Shibuya and creating green spaces.

10. La Senne, Brussels, Belgium // Concealed by 1996

The historic Senne River flows beneath Brussels. | Mark Lovatt/Moment Open/Getty Images

The historic Senne River flows beneath Brussels. | Mark Lovatt/Moment Open/Getty ImagesBrussels derives its name—and its foundation—from the Senne River. One of the earliest mentions of Brussels dates to the 10th century, when it was known as Bruocsella, meaning “settlement in the marshes.” Spanning 62 miles, the Senne traverses three Belgian regions before reaching the North Sea, with over nine miles running through Brussels. Lambic enthusiasts can thank the river, as the beer undergoes spontaneous fermentation from wild yeasts native to the Senne valley.

However, by the late 1800s, city officials began enclosing the river due to pollution and poor water quality. Frequent floods and cholera outbreaks fueled Belgians’ desire to hide it from view.

Today, while other European rivers evoke romantic sentiments, Belgians remain wary of their buried river, with sections being covered as late as 1996. Recent attempts to uncover parts of the Senne faced opposition from residents who recalled it as a stagnant swamp. However, some portions have been restored: Over the past decade, the city has worked to revive fish and plant life in the river, with the European Union providing funding in line with its climate change objectives.