Whether individuals rely on the legal system or take matters into their own hands as vigilantes, the idea of rightful retribution has existed since ancient times. But what occurs when justice cannot reach its intended target? What alternatives do people turn to?

In numerous historical instances, the only recourse was to seek divine intervention from gods or spirits, hoping they would intervene. As various cultures evolved distinct religious and spiritual beliefs, they also devised unique methods to inflict harm upon one another.

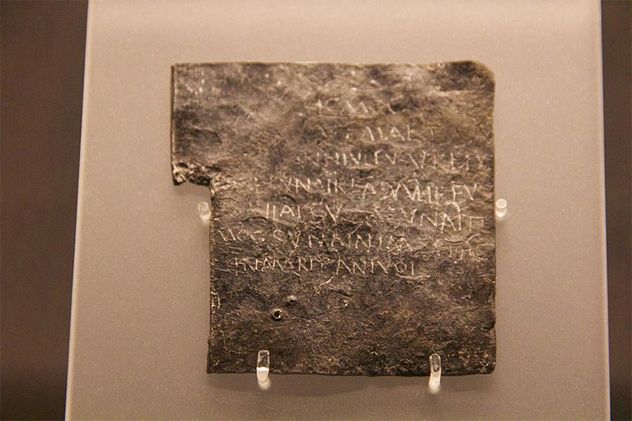

10. Roman Curse Tablets

In Roman Britain, placing a curse on someone was a straightforward process. All that was required was a piece of lead (though wood or stone could suffice if lead was unavailable) and a tool to engrave it. Once prepared, the next step was deciding what to inscribe on the curse tablet.

Creating curse tablets was simple. The person casting the curse would focus on a specific individual, often through an action (like invoking punishment on an unidentified thief). They would then elaborate on the desired consequences for the wrongdoer. Some curses were highly imaginative, such as one that read, “ . . . so long as someone, whether slave or free, remains silent or knows anything about it, may they be cursed in their blood, eyes, and every limb, and may their intestines be utterly consumed if they have stolen the ring.”

After completing the tablet, the individual would then need to place it in a location where a deity could easily find it. A favored spot for ensuring a god or goddess would notice the curse was Bath, England, where shrines honored the hybrid Celtic-Roman goddess Sulis-Minerva. Over 130 tablets have been discovered in the shrine’s waters, each containing a request for the goddess to bring misfortune upon someone.

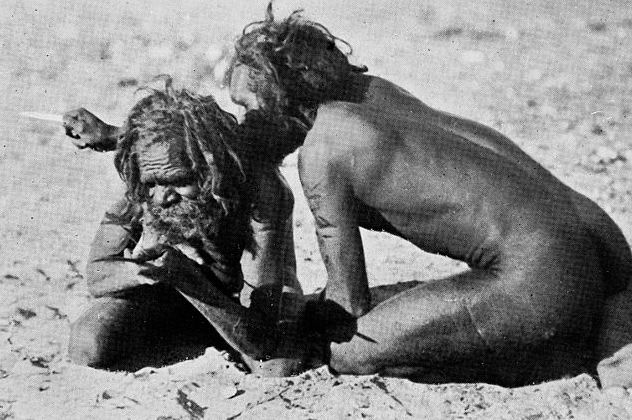

9. Bone Pointing

When enjoying spare ribs, be cautious about how you dispose of the bones afterward—they are tied to an ancient Aboriginal method of cursing someone.

The Australian tradition of invoking spiritual destruction on someone is known as “bone pointing,” which may sound harmless initially. The tool used is a sharpened shin bone adorned with human hair at one end and a cylinder carved from another shin bone at the other. Once this “death bone” is crafted and empowered, it becomes ready for use.

A group then gathers to direct the bone toward the intended victim. The curse only becomes effective after the victim is informed of it and, crucially, if they believe in its power. If both conditions are met, the curse will take hold.

Although rarely used today, there was an instance in 2004 where the bone was directed at Australian prime minister John Howard. Fortunately, it appeared to have no harmful effect on him.

8. The Evil Eye

Have you ever caught a stranger glaring at you for no apparent reason? Nowadays, you might dismiss them as rude, but in earlier times, there was a genuine possibility that you were being cursed.

The evil eye was an unusual curse. It could be cast unintentionally, simply by “looking at something the wrong way.” A harsh stare could cause illness or even damage structures. This curse was particularly dangerous because anyone could cast it on you, leaving you clueless about the source.

Babies and children were the most vulnerable to the evil eye, primarily because they often received excessive praise. Such admiration was thought to attract the evil eye, and the most effective way to neutralize the curse was to spit in the child’s face. While this left the child bewildered, it also diminished their perceived value, thereby warding off the curse.

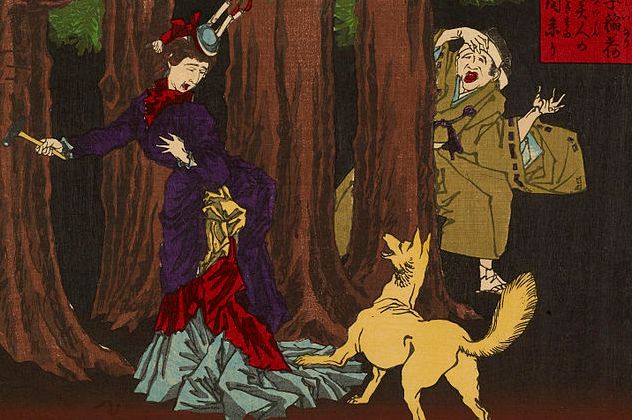

7. Ushi No Koku Mairi

A word of caution: If your partner leaves home around 1:00 AM after an argument, they might be plotting revenge.

This curse is known as Ushi no Koku Mairi, translating to “Shrine Visit at the Hour of the Ox” in Japanese. The Hour of the Ox refers to the time between 1:00 AM and 3:00 AM. The extended “hour” is due to the zodiac system, where each animal is assigned a specific time frame. Since oxen typically worked during the day, they were allocated the early morning hours.

To execute the curse, the person seeking revenge would create a straw effigy (called a waraningo) resembling the target, incorporating something personal like blood. During the Hour of the Ox, they would stealthily visit a nearby Shinto shrine and locate the shinboku, a sacred tree believed to house spirits. The effigy would then be nailed to the tree, completing the curse.

However, there are strict conditions: the ritual must occur during the Hour of the Ox, as this is when malevolent spirits are most active. It must also be carried out in complete secrecy. If anyone witnesses the act, the curse will reverse—unless all witnesses are silenced.

6. Nidstang

If you encounter someone carrying a horse’s skull on a pole, be cautious of their motives. While it might seem obvious, they could be attempting to cast a nidstang, a Viking curse.

The horse’s skull mounted on a pole is referred to as a “Niding Pole” and serves as the focal point of the curse. Historically, these poles stood about 3 meters (9 feet) tall and were inscribed with insults and runes before being planted in the ground with the skull directed toward the home of the wrongdoer. The ritual invoked Hela, the goddess of death, not to harm the individual but to provoke the earth spirits.

The pole had to be placed near the cursed person’s home to disturb the earth spirits residing there. Once the spirits were angered, they would seek revenge on the inhabitant, the target of the curse. The spirits would go to great lengths to disrupt the person’s life as retribution for the defiled land, thereby completing the curse.

5. Book Curses

In medieval times, before the invention of the printing press, books were incredibly valuable. They were labor-intensive to produce and highly prized due to their scarcity. The thought of someone sneaking into your home and stealing your books while you slept was a nightmare. To prevent this, people resorted to cursing anyone who took a book without permission.

Book curses served as a deterrent against thieves. These curses were typically written by the scribe who created the book and placed in the colophon, the section detailing publication information. The curses could invoke any deity the scribe chose, and in medieval Europe, they often called upon God. Scribes had the creative freedom to craft unique and severe curses, reflecting their frustration after the painstaking effort of hand-copying an entire book.

How severe were these curses? Consider this example from a book in a Barcelona monastery, which also takes a jab at negligent borrowers:

For him that stealeth, or borroweth and returneth not, this book from its owner, let it change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with palsy, and all his members blasted. Let him languish in pain crying out for mercy, & let there be no surcease to his agony till he sing in dissolution. Let bookworms gnaw his entrails . . . when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of Hell consume him forever.

It almost makes library fines seem tolerable.

4. Catholic Anathemas

Curses are often associated with dark magic or voodoo, but the Catholic faith demonstrates that even those aligned with spiritual light have employed them. Anathemas, for instance, are a form of curse used within the Church.

The modern equivalent of an anathema is Catholic excommunication, a severe penalty no one would desire. Historical anathemas, as recorded in the Roman Pontifical, were far more terrifying. For example, this passage condemns those who lead holy nuns astray:

But if anyone shall dare attempt such a thing, let him be accursed (maledictus) at home, and abroad; accursed in the city and in the field; accursed in waking and sleeping; accursed in eating and drinking; accursed in walking and sitting; accursed in his flesh, in his bones, and from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head let him have no soundness.

Some individuals simply never get a moment of relief.

3. Egyptian Curses

The term 'curse' often brings to mind tales like the curse of Tutankhamun. Whether these stories are fact or fiction, exploring Egyptian history reveals the origins and beliefs surrounding these infamous curses.

Egyptian curses were not created out of malice or amusement; they were rooted in the belief that the deceased's body was vital to their spirit. If the body decayed, the spirit faced the risk of perishing. These curses served as protective measures to ensure the spirit's survival rather than acts of vengeance.

As a result, curses were not placed inside burial chambers but rather at the tomb's entrance. This was akin to posting a warning sign to deter looters, ensuring the deceased's body—and thus their spirit—remained intact.

What kind of warnings adorned these tombs? A variety of threats were used, such as: “I shall seize his neck like that of a goose,” “His heart shall not be content in life,” “His office shall be stripped from him and given to his enemy,” and even “He shall not exist.” These messages were undeniably effective.

Understanding the purpose of these curses sheds light on the uproar caused by the inscription above Tutankhamun’s tomb: “Death Shall Come on Swift Wings to Him Who Disturbs the Peace of the King.” Whether the tragedies following the tomb's opening were due to a curse or coincidence remains debatable, but the Egyptians certainly made their intentions clear.

2. Nkisi Nkondi

Throughout history, there have been instances where local justice systems failed to maintain peace. While some societies opted for stricter laws or better-trained police, one civilization resorted to hammering metal nails into vessels representing the dead.

In the Kongo region, people crafted small, human-shaped vessels known as nkisi. These were made by spiritual experts called nganga, who adorned them with items like cloth and bells to enhance their spiritual energy. These vessels served as conduits for spirits, aiding in healing rituals.

While this sounds peaceful, the nkisi had a darker counterpart: the nkisi nkondi. The term nkondi translates to “hunter at night,” hinting at its role as a protector of the innocent and a punisher of wrongdoers. When someone fell ill or faced misfortune, they often blamed a witch in their community. To seek retribution, the victim would consult an nganga, who would drive a nail into the nkisi nkondi. This act activated the spirit within and conveyed the desired punishment for the accused witch, leaving the spirits to carry out the justice.

In addition to warding off evil, nkisi nkondi could also be employed to formalize agreements. When an oath was made, a nail would be driven into the nkisi nkondi to awaken the spirit. This ensured that if the oath was broken, the spirit would exact retribution on the oath breaker.

1. Graffiti

Curses are the last thing you’d expect to find in a cathedral. However, discoveries by the Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey reveal a surprising history of such inscriptions.

Medieval church graffiti differed significantly from modern street art. Rather than personal tags, these inscriptions often included prayers and appeals to God, etched into cathedral walls.

However, the walls of Norwich Cathedral revealed more than just prayers. Researchers uncovered mysterious, unintelligible writings. Upon closer inspection, they realized the text was written upside down. One such inscription simply bore the family name “Keynsford.”

Was this an attempt at artistic reverse writing? Unlikely. It’s more probable that someone was cursing the Keynsford family. In medieval times, inverting text symbolized malicious intent. The upside-down name likely expressed a wish for the family’s downfall. Further evidence lies in the Moon symbol etched below the text, commonly associated with curses.

The discovery of two other inverted names in the cathedral suggests people frequently used sacred spaces to cast curses. At least the targets could clearly see the ominous messages left for them.