Magenta: Known for its reddish-purple hue, it appears in red onions, January’s birthstone, and the 2023 Pantone Color of the Year. Surprisingly, magenta isn’t a real color.

“Magenta doesn’t correspond to a specific light wavelength like other colors. Instead, our brains generate it when they detect both red and blue light, filling in the gap with this unique shade,” explains Terry Mudge, co-author of The Universe in 100 Colors: Weird and Wondrous Colors from Science and Nature. “It’s a fascinating twist in the color narrative, showing how our perception is shaped not just by the external world but also by our brain’s interpretation.”

The Universe in 100 Colors takes readers on a vivid exploration of the myriad shades that define our world. From the recognizable—ivory, poppy red, chalkboard green—to the extraordinary, like cosmic void (a black representing absolute nothingness) or radium decay (the faint green glow of a chemical reaction), the book categorizes colors as contextual (changing with their environment) or fixed (consistent, like a lemon’s yellow rind). Enhanced by stunning large-format images and detailed histories, it reveals the fascinating origins of each hue.

The book delves into the science of color perception and explores how humans have utilized, understood, and valued color throughout history. “Color helps us identify safe foods and threatening animals. It influences our emotions, decorates our homes, and serves as a medium for communication and storytelling. Color is deeply intertwined with human existence,” says co-author Tyler Thrasher in an interview with Mytour. “It’s intriguing how we’re so captivated by this particular way of interpreting the world around us.”

Featuring a curated collection of paints, dyes, and pigments, the book highlights their intriguing—and sometimes perilous—histories. Below are 10 examples from The Universe in 100 Colors, available now from Sasquatch Books.

Carmine

Derived from dried and crushed cochineal insects. | © raptorcaptor/Adobe Stock, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

Derived from dried and crushed cochineal insects. | © raptorcaptor/Adobe Stock, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksSome colors are part of our daily lives, both as consumer products and edible ingredients. Carmine red is a prime example. This rich crimson hue is used in foods, drinks, toys, packaging, and manufacturing. Its history as a dye, however, traces back to 700 BCE.

The term carmine often describes a range of deep, blood-like reds, but it originally comes from the scale insect Dactylopius coccus. Female insects are collected, boiled in a sodium carbonate solution to eliminate impurities, and processed to extract carminic acid. This acid is then isolated to produce crimson lake, a fine red powder used in dyes for paints, pigments, and food. To ensure it adheres to natural fibers, it is mixed with a mordant, similar to avocado tannin.

Carmine red remains widely used in food and medicine today. The processed remains of countless scale insects are consumed daily—check the ingredients of your favorite red candy or snack, and you might spot “cochineal extract” on the label. (The term “dissolved insects” was likely deemed less marketable.) Exciting advancements are underway, such as engineering microorganisms to produce the pigment, making it suitable for vegan diets.

Egyptian Blue

A bas-relief sculpture located in the temple of the goddess Hathor at Dendera, Egypt, built during the late Ptolemaic period. | © Hemro/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

A bas-relief sculpture located in the temple of the goddess Hathor at Dendera, Egypt, built during the late Ptolemaic period. | © Hemro/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksEgyptian blue, a mesmerizing pigment, holds the distinction of being humanity’s first synthetic color, originating in the 3rd millennium BCE. This striking azure hue was used to decorate pharaonic monuments, symbolizing the sky, water, and the Nile River. Beyond its historical importance, Egyptian blue boasts remarkable optical properties.

Creating this pigment involves heating quartz, copper, alkali, and lime to temperatures as high as 982°C (1800°F) for several hours, followed by grinding the result into a fine powder. Despite its seemingly straightforward process, the technique was lost for nearly a millennium until scientists rediscovered it in the 1800s by analyzing ancient samples.

Under normal light, Egyptian blue appears as a soft, matte blue. However, when exposed to infrared light, it fluoresces intensely, emitting infrared radiation more effectively than any other known material. This unique trait, unknown to the ancient Egyptians, allows modern infrared imaging to detect its presence, aiding in the identification of archaeological sites rich in this pigment.

Modern science has quickly recognized its exceptional value. Researchers are now exploring its extraordinary infrared properties for applications in communication technologies, where it could enhance signal strength, enabling faster and more efficient data transmission.

The evolution of Egyptian blue, from its use in ancient civilizations to its role in modern laboratories, symbolizes a remarkable blend of history and innovation, highlighting the unpredictable nature of scientific progress.

Imperial Yellow

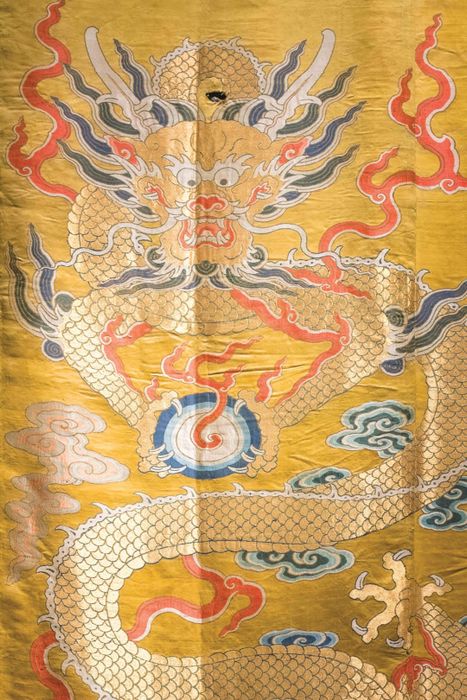

A silk panel featuring a dragon adorned with finely ground imperial yellow dye. | © Malcolm Park/Alamy, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

A silk panel featuring a dragon adorned with finely ground imperial yellow dye. | © Malcolm Park/Alamy, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksThroughout history, color has been a powerful tool for expressing status, wealth, and authority. In Chinese culture, specific hues were exclusively assigned to certain individuals or roles, with one pigment reserved solely for the emperor.

During the Zhou dynasty in China (1046–256 BCE), a system of customs and regulations around colors, patterns, and attire began to develop. Specific colors and designs were assigned to different ranks within the court or royal families. The rarer and more challenging a color was to produce, the more it was considered appropriate for the highest authority.

In traditional Chinese medicine’s five elements theory, yellow symbolizes the earth. Its significance grew when it became associated with the emperor. The first recorded instance of an emperor wearing yellow was Emperor Wen of Sui before 600 CE. Later, during Emperor Gaozong’s reign in the Tang dynasty (649–683 CE), yellow was restricted to the emperor and high-ranking family members. Linked to the sun, laws were enacted to prohibit others from wearing reddish-yellow garments. As a Confucian saying goes, “Just as there cannot be two suns in the sky, there cannot be two emperors on earth.” These laws remained until the Qing dynasty’s fall in 1912 after the Xinhai Revolution.

Yellow’s royal status was also due to the labor-intensive process of creating the pigment. It involved harvesting Chinese foxglove tubers, grinding them into a paste, and applying it to fabric. About seven cups of dye were needed to color just 50 square feet of fabric, making it both rare and costly.

Mauveine

The term ‘mauve’ originates from the ‘Malva’ (mallow) flower. | © Herlock_00/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

The term ‘mauve’ originates from the ‘Malva’ (mallow) flower. | © Herlock_00/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksMauveine, also known as Perkin’s mauve, emerged from a fortunate accident. Chemist William Henry Perkin discovered this captivating pigment while attempting to develop a cure for malaria. Many groundbreaking discoveries have been made while pursuing other ambitious goals.

In 1856, at just 18 years old, Perkin was tasked by his professor with synthesizing quinine, the primary treatment for malaria at the time. After numerous failed attempts, one experiment left behind a black residue with vibrant purple traces. Recognizing the potential of this accidental creation, Perkin quickly moved to produce it commercially. The dye gained rapid popularity in the fashion and textile industries, dominating the market for nearly a decade before being replaced by safer synthetic alternatives that avoided the use of aniline, a key component in mauveine production linked to an increased risk of bladder cancer.

Mauveine is celebrated as one of the first synthetic dyes created in a laboratory, revolutionizing the dye industry. Its success demonstrated the vast potential of synthetic dyes, which soon surpassed natural pigments in both versatility and market dominance. Within 12 years of mauveine’s invention, over 50 manufacturers were producing synthetic dyes, competing to offer affordable and widely available colors. This shift forever transformed how we create, use, and profit from color.

Mummy Brown

A preserved ferret mummy. | © schusterbauer.com/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

A preserved ferret mummy. | © schusterbauer.com/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksIn the quest for the perfect colors, humans have gone to extreme lengths. From crushing countless insects and snails to poisoning themselves or desecrating graves, few obstacles have deterred the pursuit of coveted pigments.

Mummy brown was favored by artists for its range of ocher and umber tones. Its yellowish-brown shades were ideal for dark landscapes and natural scenes, but its production involved grave robbing—often targeting non-white burial sites. Egyptian tombs were frequently plundered for mummies, and when these were scarce, the bodies of enslaved individuals were exhumed instead. Occasionally, mummified animals were also used. This pigment was thin, allowing it to layer over other colors for shading, but its natural fats caused reactions with other pigments, altering their appearance.

Artists like Eugène Delacroix, Sir William Beechey, and Edward Burne-Jones used mummy brown, with Burne-Jones reportedly burying his supply upon discovering its origins. As mummy supplies dwindled and its popularity faded, it was replaced by a more ethical alternative made from kaolin, quartz, goethite, and hematite.

Orpiment

Orpiment deposits near Champagne Pool in the Wai-O-Tapu geothermal area, New Zealand. | © Steve Todd/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

Orpiment deposits near Champagne Pool in the Wai-O-Tapu geothermal area, New Zealand. | © Steve Todd/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksCertain colors evoke dreams of vast riches, eternal life, or boundless creativity. Minerals or pigments resembling metallic gold have fascinated rulers, alchemists, and artists for centuries, even when their pursuit led to fatal poisoning. Orpiment, a vivid orange mineral rich in arsenic, often found near volcanic activity alongside realgar, belongs to the deadly category of colors that can kill.

Every aspect of orpiment is hazardous, from its mining locations to its atomic structure. Like realgar, its arsenic sulfide composition is highly toxic, particularly when heated to release its brilliant golden-orange hues. Before modern chemistry, alchemists heated orpiment in furnaces, seeking to synthesize gold, often poisoning themselves in the process. Meanwhile, masterpieces like Raffaello Sanzio’s The Sistine Madonna and Giovanni Bellini’s The Feast of the Gods showcased the pigment’s vibrant allure. Due to its toxicity, orpiment was eventually replaced by safer cadmium- and chromium-based yellows, saving countless lives in the creative community.

Pompeiian Red

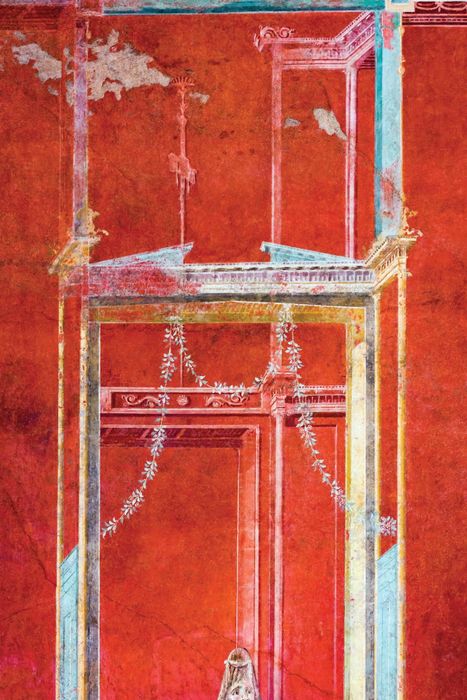

Fresco of the Portico, dating between 62 and 79 CE, from the Temple of Isis in Pompeii. | © ArchaiOptix/Wikimedia, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

Fresco of the Portico, dating between 62 and 79 CE, from the Temple of Isis in Pompeii. | © ArchaiOptix/Wikimedia, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksDuring the mid-18th century, archaeologists unearthed the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, preserved under ash and pumice from Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 CE. The city revealed a wealth of opulence, including numerous frescoes with distinctive red backgrounds, now called Pompeiian red. The pigment, derived from local iron-rich clay, was widely used throughout the city.

As Pompeii’s aesthetic legacy gained fame, Pompeiian red became synonymous with the city’s sophistication and luxury. This discovery sparked the Pompeiian Revival design movement, which flourished alongside ongoing archaeological excavations into the early 20th century. The trend left a lasting impact on Europe and the United States, influencing furniture, architecture, and design with its signature red hues and slender structural elements.

Recent studies, however, reveal a fascinating twist in the story of this iconic color. Detailed analysis indicates that the famous red walls of Pompeii might have originally been yellow. Yellow ocher, a pigment known to turn reddish under extreme heat, could have undergone this transformation during the volcanic eruption. This suggests that Mount Vesuvius not only devastated Pompeii but also created the city’s now-iconic hue.

Prussian Blue

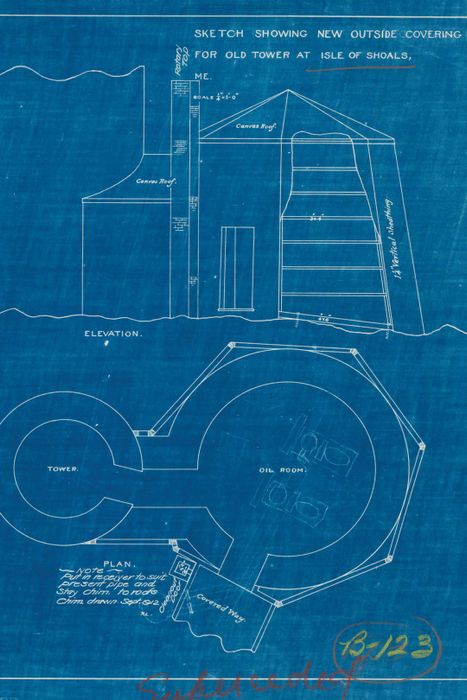

A blueprint for a building on the Isle of Shoals. | © Wikimedia, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

A blueprint for a building on the Isle of Shoals. | © Wikimedia, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksWhile many colors are confined to specific uses—as pigments, medical treatments, or chemical components—Prussian blue is unique for its wide-ranging historical influence across multiple fields.

Prussian blue was accidentally discovered in 1706 by paint maker Johann Jacob Diesbach. While attempting to produce red carmine pigment, a contaminated ingredient triggered an unexpected chemical reaction, resulting in iron ferrocyanide. Diesbach recognized the unique blue hue and marketed it as a cost-effective substitute for pricey ultramarine.

More than a century later, British engineer Joseph Whitworth utilized Prussian blue to develop engineer’s blue, a grease used to detect imperfections on metal surfaces requiring precision. This innovation significantly advanced the creation of high-precision instruments.

In 1842, chemist John Herschel found a photosensitive method to produce Prussian blue, revolutionizing document duplication. This technique was particularly useful for creating blueprints of technical drawings. Botanist Anna Atkins, a friend of Herschel, used this method to photograph her algae collection, publishing the first photo book, Photographs of British Algae.

Beyond its industrial and artistic uses, Prussian blue is also a vital treatment for heavy metal poisoning caused by thallium and radiocaesium. It is even available in pharmaceutical-grade pill form for medical purposes.

From transforming the art world as an affordable pigment to driving engineering innovations and serving as a critical medical treatment, Prussian blue has repeatedly demonstrated its remarkable versatility.

Scheele’s Green

Vintage wallpaper showcasing one of the many applications of Scheele's green. | © Aaren Goldin/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

Vintage wallpaper showcasing one of the many applications of Scheele's green. | © Aaren Goldin/Shutterstock, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksScheele’s green stands out as one of the most hazardous pigments in history. Created in 1775 by German-Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, this vivid, almost harsh green was made by combining copper, oxygen, and arsenic to produce cupric arsenite. Despite its toxicity, it became widely used in Victorian-era paints for children’s toys, clothing dyes, wallpapers, and more.

Scheele’s green is infamous for its role in deadly wallpapers. Certain organisms could feed on the arsenic-laden paper, releasing toxic gases that slowly poisoned occupants. Fungi like Scopulariopsis, thriving in damp, arsenic-rich environments, may have contributed to this. It is theorized that Scheele’s green wallpaper caused Napoleon’s death, as high arsenic levels were detected in his body.

History is filled with harrowing accounts of workers suffering agonizing deaths from arsenic poisoning. From miners extracting cupric arsenite for pigments to children in poorly lit workshops dusting artificial leaves with Scheele’s green powder to make them look vibrant, the dangers were widespread. Eventually, public outrage, government regulations, and shifting trends led to the discontinuation of this deadly pigment.

Tyrian Purple

A view of the underside of the regal murex sea snail. | © Jon G. Fuller/VWPics/Alamy, courtesy of Sasquatch Books

A view of the underside of the regal murex sea snail. | © Jon G. Fuller/VWPics/Alamy, courtesy of Sasquatch BooksObtaining purple historically required extreme efforts, making it a color reserved for royalty, the affluent, or ceremonial use. Tyrian purple, derived from predatory sea snails, is a prime example of this costly and labor-intensive process.

Tyrian purple, also called imperial or royal purple, was one of the most labor-intensive and costly dyes to produce. Tens of thousands of snails were needed to yield just a few grams of dye, enough only to trim a single garment, making it exorbitantly expensive. It was said that fabric dyed with this pigment was worth its weight in silver. In Rome, it became such a potent status symbol that, like imperial yellow, it was eventually restricted to the emperor.

The dye was made from the mucus of predatory sea snails, which they secrete to immobilize prey, protect their eggs, or when disturbed by humans. Extracting this mucus involved either “milking” the snails (a more sustainable method) or crushing them. The dye’s vibrant purples and burgundies depended on its freshness, requiring extraction to occur near the snails’ habitat.

In November 2020, a team led by Byung-Gee Kim at Seoul National University successfully synthesized 6,6’-dibromoindigo, the molecule behind Tyrian purple. They achieved this by genetically modifying Escherichia coli bacteria to produce the molecule using three engineered enzymes. The resulting 6,6’-dibromoindigo was then centrifuged into pellets for fabric application, eliminating the need to harvest thousands of snails.

Excerpted from The Universe in 100 Colors: Weird and Wondrous Colors from Science and Nature by Tyler Thrasher and Terry Mudge. September 24, 2024, Sasquatch Books. Published with permission.