Science fiction tales often feature iconic elements like laser guns, robots, and, most notably, flying cars. Unlike traditional aircraft, flying cars are unique because they seamlessly transition between driving on roads and soaring through the skies. Typically, they resemble ordinary vehicles but possess the extraordinary ability to fly—once you know which button to press.

The 20th century was a hotbed of groundbreaking inventions, and flying cars were no exception. From brilliant designs to comically flawed attempts, these creations have left an indelible mark on our history. Below, we explore ten fascinating flying cars that have captured imaginations over the decades.

10. Curtiss AutoPlane

The Curtiss AutoPlane marked the world's first real-world encounter with a flying car, stepping out of the realm of fiction. In 1917, aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss reimagined his Curtiss Model L trainer, a triplane with a one-hundred-horsepower engine, by integrating its components into an aluminum Model T chassis. This innovative hybrid aimed to blend the practicality of a car with the thrill of flight.

The vehicle featured a car-like steering wheel to control the front tires and was powered by a rear-mounted propeller for both ground and air movement. Dubbed the 'limousine of the air,' it never achieved true flight, managing only brief hops before being shelved at the onset of World War I.

9. Jess Dixon’s Flying Auto

Shrouded in mystery, Jess Dixon’s flying car is nearly legendary, with its existence documented only by a single photograph and a fleeting mention in an Andalusia, Alabama, newspaper. The image, believed to date back to around 1940, shows Dixon with his creation. While aviation enthusiasts classify it as a flying car, its design—featuring two counter-rotating overhead blades—places it closer to a 'roadable helicopter' or gyrocopter capable of both flight and road travel.

The Flying Auto was equipped with a modest forty-horsepower engine, and its tail vane was maneuvered using foot pedals, enabling mid-air turns. Reportedly, it could achieve speeds of up to one hundred miles per hour (160 kph) and was capable of flying in any direction—forward, backward, sideways—and even hovering. Impressive for a flying car that vanished into obscurity shortly after its debut.

8. ConvAirCar

The Convair Model 116 Flying Car debuted in 1946, resembling a compact airplane fused onto a car—a design that was precisely that. Its wings, tail, and propeller were detachable, allowing the plastic-bodied car to function as a standard road vehicle. When aerial travel was needed, the plane components could be reattached, transforming it back into a flying machine.

Only one prototype of the 116 model was built, completing sixty-six flights. Later, designer Ted Hall upgraded it to the Convair Model 118, replacing the 130-horsepower engine with a more robust 190-horsepower version for enhanced aerial performance. Convair ambitiously planned to produce 160,000 units, but the dream was shattered when a prototype crashed in California. The pilot, unaware that the plane’s fuel gauge was separate from the car’s, ran out of mid-air fuel, highlighting the risks of dual-purpose vehicles.

7. Curtiss-Wright VZ-7

The Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 emerged from the US military's early foray into the flying car sector. Designed as a futuristic flying jeep, it combined the ruggedness of a ground vehicle with the added capability of flight. Developed by Curtiss-Wright, a company born from the merger of the Wright Company (founded by the Wright Brothers) and Curtiss Aeroplane (led by Glenn Curtiss), it symbolized the union of two once-bitter rivals in aviation history.

The VZ-7 was a VTOL (Vertical Take-Off and Landing) vehicle powered by four upright propellers located behind an open-air cockpit. Pilots controlled its movement by adjusting the speed of individual propellers, enabling it to tilt and maneuver in various directions. Despite its innovative design, the exposed propellers made it dangerously unsafe, leading the army to abandon the project in 1960, just two years after it began.

6. Piasecki AirGeep

After the VZ-7 project was shelved, the army shifted its focus to the Piasecki VZ-8 AirGeep, a radically different design. By this time, helicopters were already widely used, but the military sought a smaller, more agile vehicle that required minimal training to operate.

The AirGeep underwent seven iterations, each retaining the core design of two large vertical propellers at the front and rear, with a central pilot seat and three or four wheels for ground mobility. While the initial version had a flat design, later models featured a curved, V-shaped frame. The navy even experimented with adding floats for maritime use, but the concept, along with the entire program, was eventually scrapped.

5. AVE Mizar

In 1971, California-based Advanced Vehicle Engineers set out to create a flying car inspired by the 1940s ConvAirCar. Their solution was to fuse a Ford Pinto with a Cessna Skymaster, resulting in the peculiar hybrid known as the Ave Mizar.

The ground vehicle portion of the Ave Mizar closely resembled a standard Ford Pinto. The Pinto's engine accelerated the craft for takeoff, after which the plane's propeller took control. During landing, the car's brakes handled deceleration. Tragically, in 1973, just a year before planned mass production, a prototype's right wing failed mid-flight, causing a fatal crash that ended the project.

4. Super Sky Cycle

Even in the modern era, practical flying cars remain elusive. The Butterfly Super Sky Cycle, for instance, bears a striking resemblance to Jess Dixon’s legendary Flying Auto. Functionally, it’s a roadworthy gyrocopter, featuring a folding propeller and a swiveling tail for aerial navigation.

The Super Sky Cycle, constructed in 2009, is now (as of 2012) fully street-legal, requiring only a motorcycle license and a pilot’s license for operation. Its compact design allows it to fold down to just seven feet (2.1m), making it easy to store in most garages. Produced by Butterfly Aircraft LLC, these gyrocopters are sold as DIY kits. While it may not match the traditional image of a flying car, it’s accessible to anyone willing to invest $40,000.

3. AirMule

The AirMule functions more as a flying ambulance than a car, but the concept remains similar. Developed by Israel’s Urban Aeronautics, its primary role is to support search and rescue operations. While it matches helicopter speeds, its compact design allows it to navigate spaces too tight for conventional helicopters.

Resembling the military’s AirGeep designs from the 1970s, the AirMule has one key distinction: it’s remotely operated. This unmanned vehicle could either become a lifesaving tool or, given the history of UAVs, a weapon. Urban Aero plans to control it via a remote pilot using flight controls and monitors, akin to managing a plane in a sophisticated video game.

2. PAL-V One

The PAL-V One, a Dutch innovation, injects a dose of sophistication into the autogyro world. Unlike traditional designs, it features a single engine that seamlessly shifts power between the wheels and the propeller, depending on whether it’s on the ground or in the air.

One of the PAL-V’s standout features is its operational ceiling below four thousand feet (1,200 m), eliminating the need for flight plans—a significant barrier for modern flying cars. This innovation could pave the way for GPS-guided 'digital corridors,' creating organized aerial pathways akin to highways in the sky.

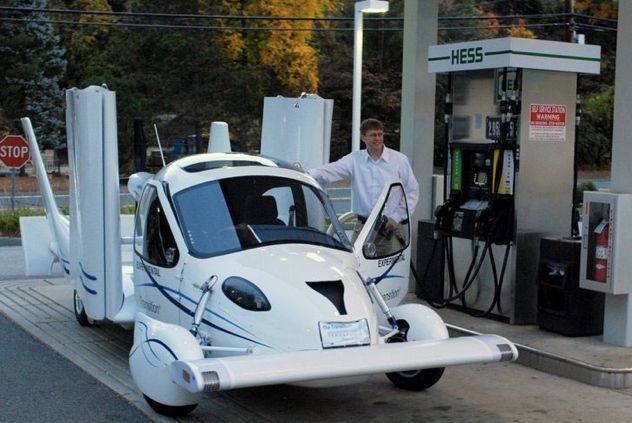

1. Terrafugia Transition

The Terrafugia Transition achieved its maiden test flight in 2009, followed by numerous enhancements and redesigns, culminating in a second successful flight in 2012. This innovative vehicle combines the sleek, aerodynamic profile of an airplane with foldable wings that pivot vertically for ground use. It boasts a top speed of 70 mph (110 km/h) on roads and 115 mph (185 km/h) in the air, offering a glimpse into the future of transportation.

A major hurdle for Terrafugia was the Transition's weight, which exceeded FAA limits due to road safety features like bumpers and airbags. In 2010, the FAA granted an exemption, reclassifying the vehicle to simplify licensing requirements. Despite this breakthrough, the Transition remains a luxury item, priced higher than a Lamborghini.