Throughout time, humans have often been engaged in conflict with other nations or societies, but there have also been numerous occasions where humans have found themselves battling animals.

There are several reasons why animals have become the focal point of human aggression. In some cases, they inhabit areas where wars are being fought, inadvertently becoming participants, or are slaughtered as a means of punishing local populations. Other times, certain animals are simply viewed as pests.

At times, animals have emerged victorious, while at others they have been defeated. However, whenever a native species is unjustly persecuted in large numbers, it leads to an ecological imbalance that causes additional problems in the future.

Even today, humans continue to wage battles against animals, despite the lessons learned from past encounters with various species across the globe.

10. The 'Four Pests' Campaign

Mao Zedong's attitude towards nature was evident throughout his leadership of China from 1949 to 1976. His motto, 'Man Must Conquer Nature,' was central to his Great Leap Forward initiative.

In addition to deforestation and shifts in agricultural practices, one drastic policy was the 'Four Pests' campaign, aimed at eradicating flies, mosquitoes, rats, and sparrows. This included mass killings of sparrows, disrupting the ecosystem because they played a crucial role in controlling pests. As a result, crops became vulnerable to insects like locusts, causing a catastrophic famine that resulted in millions of deaths.

Critics of these policies faced severe punishment, such as hydro-engineer Huang Wanli, who was sent to a labor camp for opposing a dam project.

Even after the early 1960s, when the Great Leap Forward was abandoned, farmers were still pressured to focus on grain production, further damaging the environment and exacerbating the struggles of the Chinese people.

The Battle of Ramree Island, a harrowing chapter in World War II, took place off the coast of Burma (now Myanmar). The island saw several intense military engagements, but none as chilling as the one in 1945 when British forces cornered approximately 1,000 Japanese soldiers in the dense mangrove swamp that stretched across 10 miles (16 kilometers) of Ramree.

In an unexpected turn of fate, the mangrove swamp, which was already a perilous environment, was also home to saltwater crocodiles – the largest predatory reptiles on the planet. With some reaching lengths of over 20 feet (6 meters) and weighing in at over 2,000 pounds (907 kilograms), even the smaller ones had the power to kill an adult human.

Around 500 Japanese soldiers managed to escape the swamp, though only 20 were recaptured. Tragically, it's believed that the other 500 perished, likely falling victim to the crocodiles. Accounts from the survivors describe terrifying moments when these massive reptiles would appear seemingly from nowhere, seizing their prey with deadly force.

The horrific events at Ramree Island earned recognition from Guinness World Records, which dubbed it the site of the 'Most Number of Fatalities in a Crocodile Attack.' However, the precise death toll remains a topic of debate among historians.

Although the exact number of fatalities is disputed, the incident remains one of the most chilling and brutal stories of nature's lethal power during wartime.

In 1871, the renowned William 'Buffalo Bill' Cody, along with a group of affluent New Yorkers, set off on an expedition to hunt buffalo in Nebraska. Despite the animals being bison, not buffalo (as true buffalo do not exist in America or Europe), their mission was part of a broader strategy by the United States Army to curb Native American populations by wiping out the buffalo that Indigenous people depended on for survival. One colonel infamously declared, 'Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.'

This systematic slaughter was viewed as a means of undermining Native American life by destroying their primary resource and forcing them onto reservations. The economic downturn of 1873 only intensified the destruction, as more hunters arrived, eager to profit from the buffalo's hides. The market was soon flooded with the pelts of thousands of buffalo, diminishing the once-prized commodity’s value.

The buffalo population plummeted as a result, and by the close of the 19th century, only a few hundred of these majestic creatures remained in the wild.

Conservation efforts to protect the species began in the 1870s, but President Ulysses S. Grant refused to approve legislation that would safeguard the buffalo. In the aftermath of the slaughter, the government responded by sending cattle to certain tribes in an attempt to replace the buffalo they had lost.

Though efforts to preserve the buffalo began too late for many herds, they marked the start of a long struggle to save the species from total extinction.

The recent designation of the American bison as the national mammal is a tribute to the species' profound historical importance.

In 1932, farmers in Western Australia were already facing hardships as a result of the Great Depression. However, their troubles escalated when around 20,000 emus, driven by their breeding season, migrated inland, threatening the crops.

In response to the destruction of their fields, Australia declared war on the emus, deploying soldiers armed with machine guns to combat the large birds. Despite several confrontations, the emus proved to be unexpectedly resilient, and the soldiers failed to secure a decisive victory.

Today, emus continue to thrive in areas outside of Perth, and their unexpected success in this peculiar conflict has even inspired the creation of an action-comedy film currently in development.

The Great Emu War stands as a strange chapter in Australian history, where humanity's battle against nature was humorously outmatched by the cunning of flightless birds.

The battle against wolves in the United States has persisted since the 19th century, driven by efforts to protect livestock from predation. In 1905, the federal government resorted to biological warfare by infecting wolves with mange. A decade later, Congress passed a law requiring the elimination of wolves from federal lands. By 1926, Yellowstone National Park saw the complete eradication of its wolf population through poisoning, shooting, and trapping.

In the 20th century, efforts to revive wolf populations were launched, with reintroduction programs and federal protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Yet these conservation initiatives have encountered significant opposition from ranchers, hunters, and landowners who continue to view wolves as a threat to livestock and game populations.

This ongoing conflict has led to heated debates, legal disputes, and contentious state and federal policies on how wolves should be managed, including decisions to remove them from ESA protections in certain regions. The war on wolves has evolved into a prolonged struggle between conservationists striving to restore and protect wolf populations, and stakeholders with opposing interests who wish to eradicate them.

The battle to control wolf populations in the U.S. is far from over, as the war between conservation efforts and those with differing views continues to unfold.

In a different chapter of American history, the Beaver Wars represented another intense conflict with the environment, as natural resources became the focal point of territorial disputes.

The Beaver Wars were a series of violent conflicts in 17th-century colonial America, sparked by the battle for control over the valuable fur trade. Various Native American tribes, French settlers, and European traders vied for dominance, knowing that access to beavers and their pelts meant immense financial gain.

The Iroquois Confederation, a powerful alliance of several tribes, emerged as the dominant force in the fur trade. They successfully wiped out rival tribes, seized control of the trade, and launched attacks on French settlements to solidify their power.

In retaliation, the French and their Native American allies launched counteroffensives, attacking Iroquois villages and English settlements. These conflicts dragged on for nearly a century, finally coming to an end with the signing of the Peace of Montreal treaty in 1701, which marked the conclusion of the Beaver Wars.

Roman venationes, or animal hunts, were a popular form of public spectacle in ancient Rome, held in grand amphitheaters. These brutal events featured either battles between wild animals or between animals and human combatants, typically captives, criminals, or professional hunters.

The venationes were a highlight of Roman entertainment, offering a grotesque yet thrilling experience for the audience, who would gather to witness these deadly contests of survival and skill.

Venationes, which originated in the 2nd century BC as part of the circus games, grew in popularity so rapidly that Julius Caesar, the Roman General, built the first wooden amphitheater specifically for these events. The demand for such spectacles was immense, prompting the sourcing of exotic animals like lions, bears, bulls, hippopotamuses, panthers, and crocodiles from across the globe to be displayed and slaughtered in public ceremonies. As many as 11,000 animals were shown and killed in these performances.

Even after the abolition of gladiator games in the 5th century, venationes persisted, immortalized in depictions on coins, mosaics, and tombs from the era. These images underscore the importance of these animal shows in Roman culture.

3. The Bear Soldier in the Battle of Monte Cassino

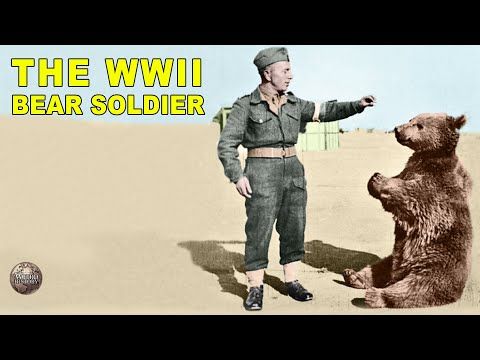

During World War II, a Syrian brown bear named Wojtek, orphaned at a young age, became an unexpected comrade to the Polish II Corps. His presence was largely unknown to those fighting alongside him.

Raised by the soldiers, Wojtek journeyed with them through the Middle East and eventually made his way to Italy. Despite the challenges of transporting a bear, he was officially enlisted as 'Private Wojtek' and became a full-fledged member of the regiment.

Wojtek quickly won the affection of his fellow soldiers, joining in their activities and even aiding them during the Battle of Monte Cassino by transporting ammunition. His contributions were so valued that he was promoted to the rank of corporal.

Following the war, Wojtek traveled with his comrades to Scotland, where he resided on a farm and became a beloved local figure.

He participated in various events, made TV appearances, and lived out a serene life until his passing in 1963.

Wojtek’s extraordinary journey has been commemorated through films, books, and statues across Poland and Britain. His service stands as a powerful reminder of the unbreakable bond between humans and animals in times of hardship.

2. The Australian 'Mouse Plague'

In 2021, Australia was struck by one of the most severe mouse plagues in its recent history, which caused widespread crop damage and a significant infestation. The outbreak was a result of favorable weather conditions, which led to a surplus of food after a lengthy period of drought and destructive bushfires.

The house mouse, which was introduced to Australia in the late 1700s, has always been a threat to the native species, competing for the same resources.

The economic toll of this plague was estimated to be around AU$1 billion, prompting financial assistance from the government and the exploration of control strategies like gene editing to reduce the mouse population. While the plague subsided by the end of 2021, experts have cautioned the public against complacency, as another such event could occur.

1. The Elephant Soldiers in the Battle of Zama

The Battle of Zama, fought in 202 BC, marked a critical point in history. It saw the Romans, led by Scipio Africanus the Elder, confront the Carthaginians, who were commanded by Hannibal. This battle ultimately brought the Second Punic War to a close.

Hannibal’s forces were heavily dependent on 80 war elephants that, unfortunately, were not yet fully trained, alongside Carthaginian soldiers who lacked significant combat experience.

When the Carthaginians charged their elephants into the Roman ranks, the Roman forces swiftly dispersed them, thanks to Scipio's clever tactic of positioning small, mobile infantry units, called maniples, with gaps in between to allow soldiers to evade the elephants’ charge.

It is believed that the Romans' loud shouts and the blaring of their trumpets caused confusion among the elephants, leading some of them to veer off course and inadvertently charge their own infantry.

By successfully neutralizing the elephant charge, the Romans gained a pivotal advantage in the Battle of Zama, securing their victory. This win marked the end of Hannibal’s influence over Carthaginian forces and dealt a crippling blow to Carthage’s ability to resist Roman domination.