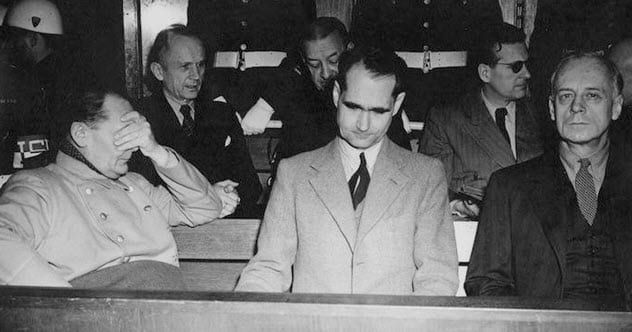

Once World War II concluded, the Nuremberg trials brought to light the heinous crimes of the Nazi regime. High-ranking officials faced prosecution, with many receiving death sentences for their roles in the Holocaust.

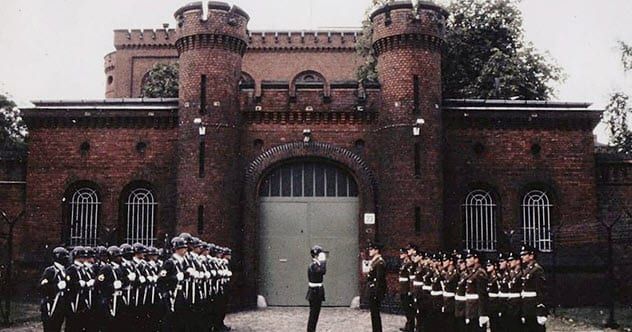

Among those convicted, seven officials—such as Karl Donitz, who succeeded Adolf Hitler—were imprisoned in Berlin’s Spandau Prison. Though the prison has since been transformed into a shopping center, the tale of the “Spandau Seven” remains a captivating blend of malevolence and brilliance.

10. Albert Speer Penned a Memoir Using Over 20,000 Sheets, Mostly Toilet Paper

Albert Speer, who served as Hitler’s Minister for Armaments and War Production, was widely recognized for maintaining the functionality of the massive German army despite relentless Allied bombings. His intellect was so esteemed that the Allies extensively interrogated him before his 1945 arrest, eager to glean insights from his expertise.

Convicted as a war criminal during the Nuremberg trials, Speer was incarcerated in Spandau Prison for two decades. In the initial ten years, he authored his two memoirs: Inside the Third Reich and Spandau: The Secret Diaries.

With assistance from a prison orderly, Speer managed to send his handwritten notes—often scribbled on toilet paper—to his wife, who forwarded them to his secretary and confidant, Rudolf Wolters. Through this network, over 20,000 sheets of his writings were smuggled out and later compiled into his published works.

Wolters also established a bank account to fund these and other efforts supporting Speer. Released in 1966, Speer had completed the first draft of Inside the Third Reich as early as 1954, a full 12 years prior to his freedom.

9. Rudolf Hess Spent Over Two Decades in Solitary Confinement

Over the years, the Nazi criminals held in Spandau were gradually released. Konstantin von Neurath was the first, freed in 1954, followed by Erich Raeder in 1955. Karl Donitz was released in 1956, Walther Funk in 1957, and finally, Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach in 1966.

This left Rudolf Hess as the only remaining inmate in Spandau. His solitary confinement has been extensively documented. For over two decades, Hess was the prison’s sole occupant, enjoying unrestricted access to the grounds and gardens.

Hess’s mental health deteriorated significantly during his imprisonment, marked by paranoia, suicidal tendencies, and instability. However, his living conditions improved over time. As he aged, he was provided with a medical orderly and even had a lift installed for his convenience.

He was frequently questioned about his ill-fated 1941 flight to Scotland and his ties to Hitler. In 1987, at the age of 93, Hess decided to end his life by hanging himself with an extension cord fastened to a window latch.

8. The Prisoners Were Constantly at Odds

The incarceration of the seven Nazis offered a revealing glimpse into the mindset of Nazi officials, laid bare by their close confinement. Reports indicate that Rudolf Hess was a solitary figure, frequently complaining of illnesses and displaying signs of mental instability. His nighttime cries of pain often led to him being administered a placebo sedative to induce sleep.

Albert Speer, though favored by the guards, remained isolated from his fellow inmates due to his meticulous personality. Meanwhile, former Grand Admirals Karl Donitz and Erich Raeder frequently clashed with each other but united against the rest of the prisoners.

Raeder was known as the prison’s chief librarian, with Donitz serving as his assistant. The other inmates dubbed them “The Admiralty.” Speer and Donitz shared a mutual disdain, with Speer’s rigid demeanor clashing with Donitz’s insistence on his status as Germany’s former head of state.

7. The Prison Operated Under a Four-Power System

One of the most unique features of Spandau Prison was its division into four sectors, each managed by Britain, France, Russia, and the US. Each nation oversaw the prison for three non-consecutive months annually, resulting in frequent handovers between the guards every month.

Brandon H. Grove, the US legal adviser, described the guard transitions as “a remarkable spectacle,” especially during the American-to-Russian handovers. This arrangement allowed Russia to maintain a diplomatic presence in West Berlin, as it was the sole location where Russian diplomats interacted with Allied diplomats.

Frequently, one nation would host the others at the prison, turning the event into a “theater-noir” of diplomatic one-upmanship. Depending on the controlling country, the prisoners received food from that nation, and the exterior guard was provided by the respective Allied or Russian military personnel.

6. The Prisoners Hated the Russian-Controlled Months

The Nazi officials incarcerated in Spandau frequently voiced grievances about the Russian administration of the prison. Reports suggest that the prisoners would put on weight during the American-controlled months but shed it during the Russian periods. They also protested the intense searchlights, which disrupted their sleep at night.

In a later-published letter, Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first postwar chancellor, highlighted the harsh treatment by the Russians as the primary cause of the prisoners’ suffering and poor conditions. Additionally, the Russians were the sole party opposed to releasing Rudolf Hess in his later years, leaving him in isolation for over two decades.

Declassified letters reveal that Moscow insisted Hess should “fully endure his punishment,” while the Allies felt compelled to shield him from the Russians’ harsh methods. Ultimately, Hess’s death appeared to be the only resolution, as it would terminate the quadripartite agreement. Upon his death, the Allies swiftly dismantled the prison and severed ties.

5. The ‘Impostor’ Conspiracy

The widely debated “impostor theory” revolves around Rudolf Hess, Spandau’s most infamous inmate. Even former US President Franklin D. Roosevelt reportedly entertained the idea, prompting the British government to conduct four separate investigations into the claim.

The theory alleges that the man imprisoned in Spandau was not Hess but an impostor. Supporters pointed to his altered physical appearance, his refusal to allow family visits for over two decades, and his apparent amnesia as evidence.

Some versions of the theory suggest that the Allies may have protected Hess from the Russians or that British agents had killed him during his captivity. Hess had been captured in Scotland in 1941 after crashing his plane during an alleged peace mission.

The theory was debunked in recent years when a DNA sample taken from Hess during his imprisonment was compared to a relative’s sample. The match was 99.9 percent, conclusively dispelling the impostor claims.

4. Albert Speer Embarked on Imaginary Global Journeys

During his time in Spandau Prison, Albert Speer adopted a highly disciplined approach to his incarceration. As documented in his memoirs and other reports, he maintained a strict routine that included physical exercise, mental stimulation, gardening, walking, and extensive reading.

Speer boasted of reading 5,000 books while imprisoned, though this number is widely regarded as inflated. He also devoted significant effort to gardening, eventually taking over the neglected plots of his fellow inmates. Occasionally, he would grant himself “breaks” from his demanding self-imposed schedule.

To make his daily walks more engaging, Speer imagined himself traveling around the globe, using books to guide his mental journeys. He visualized the landscapes and traversed these imaginary terrains in his mind.

He even meticulously calculated the distances of these virtual trips, covering over 30,000 kilometers (18,600 miles). By the end of his sentence, he claimed to be near Guadalajara, Mexico. After his release in 1966, Speer spent time in London.

3. Annual Operating Costs Reached $800,000

Spandau Prison detained seven high-ranking Nazi officials who survived the war’s conclusion, and their imprisonment was treated with utmost seriousness. The West Berlin government reportedly covered the prison’s annual operating cost of $800,000.

The facility was constantly guarded, and the inmates received better treatment than typical prisoners. Despite the strict regime, their nutritional needs were consistently met throughout the year.

Later, a $57,000 elevator was installed to assist the aging Rudolf Hess in accessing his garden safely. As more details emerge about Hess’s time in Spandau, it increasingly resembles an expensive retirement facility tailored to his comfort. The prison was unique, and such extreme measures are unlikely to be repeated.

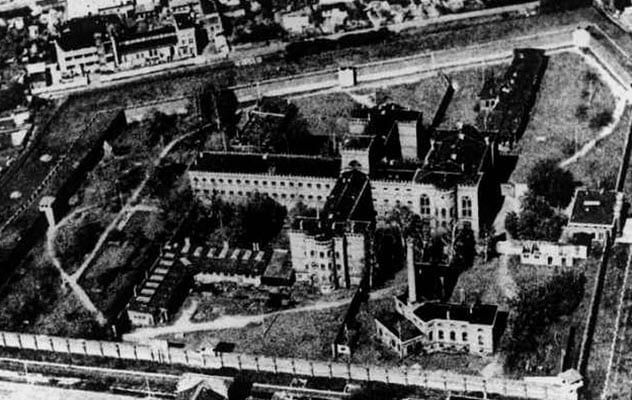

2. The Prison Was Largely Underused

Constructed in 1876, Spandau Prison initially served as a detention facility for the German military. At its height, it accommodated up to 600 inmates, featuring hundreds of cells measuring 3 meters (10 ft) by 2.7 meters (9 ft), along with a chapel, library, canteen, and gardening areas.

Following the Nuremberg trials, it was decided that the prison would house only the “Spandau Seven” Nazis. This arrangement necessitated a staff of 60 soldiers, four prison directors and their deputies, medical personnel, kitchen staff, and porters to manage just seven prisoners.

As inmates were gradually released in the 1950s and 1960s, leaving Hess as the sole prisoner, the underutilization of the prison reached absurd levels. Proposals were made to repurpose the facility, especially as West Berlin faced a severe shortage of prison space.

The West Berlin government also bore the financial burden of maintaining the prison.

1. The Prison Was Razed Without Delay

Following Rudolf Hess’s death by suicide in August 1987 at the age of 93, ending his 21 years of isolation, the decision was made to demolish Spandau Prison. Concerns that the site could become a neo-Nazi pilgrimage destination, coupled with the Allies’ desire to end their joint management agreement with Russia, drove the decision.

This move proved prescient, as Hess’s grave in Bavaria later became a gathering point for neo-Nazis, attracting rallies of up to 9,000 people before being relocated.

Spandau Prison was swiftly demolished after Hess’s death, with all debris ground into powder and either scattered in the North Sea or buried at the nearby RAF Gatow airbase. The only remaining artifact is a single set of keys, now kept in the UK.

The site where the prison once stood was transformed into a shopping center complete with a parking area.