It’s no surprise that during World War II, aircraft designers across the globe developed some truly extraordinary experimental planes. From the earliest helicopters to bombers intended for attacks on the United States, these aircraft represent some of the most fascinating designs in aviation history.

10. Blackburn B-20

During World War II, floatplanes and flying boats were crucial in the air forces of global powers. Floatplanes offered greater flexibility for water operations, but their small size often made them less maneuverable due to the large floats attached beneath. Flying boats, typically used as patrol bombers, were larger but slower. The Blackburn Aircraft Company set out to combine the best features of both, resulting in the unique B-20 design (similar to the one pictured above).

The B-20 featured a fuselage with a retractable float. When landing on water, the lower part of the fuselage would descend, improving its versatility in combat. This design also increased the wing angle, allowing for a shorter takeoff distance. Once airborne, the fuselage would reassemble, giving the aircraft a form similar to a compact flying boat. In this configuration, the B-20 faced much less drag than traditional flying boats, allowing for unprecedented speed.

Unfortunately, during a test flight, the B-20 disintegrated and crashed, resulting in the loss of several crew members. The British Air Ministry concluded that this was an isolated incident. While the B-20’s concept was sound, Blackburn shifted focus to constructing more conventional aircraft, and the experimental plane's development ceased. The B-20 ultimately went nowhere.

9. Ryan FR Fireball

In comparison to Germany and the United Kingdom, the United States lagged behind in the race to develop and deploy efficient jet aircraft. The first American jet fighter, the disappointing P-59, was no more advanced than a propeller-driven plane. Around the same time Bell was constructing the P-59, the Navy was working on the FR Fireball, a fighter with a unique power plant system. Rather than just a jet engine, the Fireball featured a propeller in the front and a jet engine at the rear.

Early jet engines were known for their slow throttle response, which made them unsuitable for carrier operations. As a result, during most maneuvers (especially takeoff and landing), the Fireball relied on its propeller engine, activating the jet engine only when additional thrust was necessary. Aside from this, the Fireball was a fairly conventional fighter aircraft, essentially a regular fighter with a jet engine mounted at the back.

Although the Fireball was officially introduced in March 1945, it never saw combat action. Only 66 units were built, and they were swiftly phased out in favor of the next generation of jet fighters. The Fireball's range was limited, and its performance was underwhelming, as it was slower than many other aircraft, even when utilizing the jet engine. Despite its shortcomings, the Fireball marked an important milestone for the Navy. It was their first jet-powered plane and the first aircraft in history to land on an aircraft carrier using jet power... albeit unintentionally. In 1945, a pilot's prop engine failed, forcing him to land on the USS Wake Island using only jet power.

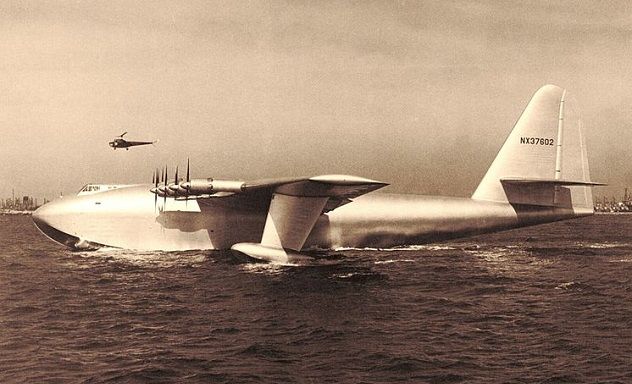

8. Blohm & Voss BV 238

The German aerospace firm Blohm & Voss was responsible for designing many of the Luftwaffe’s flying boats during World War II. As the conflict progressed, the company’s engineers went on to create even larger and more intricate flying boats. This culminated in the creation of the BV 238, a massive flying boat that was the largest aircraft ever designed by the Axis powers during the war.

Built in 1944, Blohm & Voss designed the BV 238 with the intention of providing the Luftwaffe with long-range transport capabilities. The Luftwaffe also explored the possibility of using the enormous flying boat as a long-range patrol bomber. During flight testing, it became clear that the aircraft was stable and well-suited for the transport role effectively.

The BV 238’s downfall came when three American P-51 Mustangs discovered the prototype docked at Lake Schaal. Lieutenant Urban Drew launched an attack, causing severe damage to the aircraft’s fuselage. Before the German engineers could salvage the flying boat, it sank to the bottom of the lake. With the tide of war turning against the Axis, Blohm & Voss ceased work on the aircraft. As for Lt. Drew, he went down in history, having set the record for the “largest Axis aircraft ever destroyed by an Allied pilot.”

7. Flettner Fl 282

While most people do not associate helicopters with World War II, the nations involved in the conflict were racing to develop jet propulsion technology and, at the same time, working on the first generation of helicopters. The Germans were pioneers in helicopter experimentation, maintaining an early lead. Although they spent years developing the technology, it was only with the Fl 282 that they created a design capable of mass production.

Flettner developed the Fl 282 with the unique feature of intermeshing rotors. This design involved two main rotors that angled away from one another, but their blades crossed in a synchronized pattern, preventing any catastrophic mishaps. The intermeshing rotors allowed the helicopter to eliminate the need for a tail rotor to counterbalance the torque produced by the main rotors. Aside from this unusual design element, the Fl 282 was a simple, no-frills aircraft, featuring minimal framing and an engine.

The Luftwaffe was so impressed by the Fl 282 that they placed an order for 1,000 helicopters. The planned uses included anti-submarine warfare, naval reconnaissance, and spotting. However, by the time production began in 1944, the Luftwaffe had already been pushed onto the defensive, and the fleet of Flettner helicopters never came to fruition. Only a few prototypes were completed, but they were highly regarded by the pilots who flew them. Shortly after production commenced, an Allied bombing raid obliterated the production facility, halting any further production of the helicopter. Anton Flettner, the engineer behind the project, eventually immigrated to the United States, where he contributed to the development of successful helicopters for the U.S. Air Force.

6. Kyushu J7W

One of the most strikingly futuristic airplanes of its time was the Japanese-designed J7W Shinden, featuring a canard design. This layout involves positioning the “main wing at the rear” of the fuselage with a smaller wing mounted at the front. The idea was that this innovative design would make the J7W highly maneuverable, allowing it to challenge American B-29 bombers in combat.

The interceptor was powered by a large engine that drove a six-blade pusher propeller via an extension shaft. During testing, the engine presented numerous issues, particularly overheating, even during ground trials. By the war’s end, Kyushu engineers had resolved many of the engine’s problems. Equipped with four 30mm cannons, the J7W was a heavily armed aircraft designed to take down the B-29 bombers.

Japanese Navy officials were so confident in the J7W’s potential that they ordered production before the first prototype had even flown. Fortunately for B-29 crews, the J7W only completed three test flights before the war ended, and production was never realized. During testing, the plane barely managed to accumulate 45 minutes of flight time. The war ended before the Navy could conduct further evaluations. A proposed turbojet version of the aircraft remained stuck on the drawing board.

5. Heinkel He 100 and He 113

As the Luftwaffe prepared for World War II, they considered several aircraft to succeed their primary frontline fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. One of the top contenders was the Heinkel He 100, an aircraft that was among the best in the world at the time. Although wartime documents about the He 100 are scarce, it is clear that the aircraft was a major upgrade over the Bf 109 and featured a number of qualities that would have made it highly effective against Allied pilots.

Notably, the He 100 set and held the world speed record for its class of aircraft. Despite this impressive feat, the Luftwaffe opted to continue development of the Bf 109 and its variants, and the exact reasons behind the halt of the He 100 project remain unknown.

Although the He 100 never saw frontline service, it played a notable role in early Nazi propaganda. At the start of the war, the United Kingdom lacked sufficient intelligence on the Luftwaffe, including the specifics of their aircraft lineup.

Taking advantage of this gap, Joseph Goebbels announced that the Luftwaffe was deploying a new He 113 fighter, which, in reality, was simply a repainted He 100 prototype. German publications regularly featured photos of the “new fighter” alongside reports of its combat capabilities, which made their way to the UK. The Royal Air Force grew concerned about this supposed He 113, and pilots reported encountering it. However, there was no evidence to confirm these claims. Eventually, the British Air Ministry uncovered the deception, realizing the He 113 was merely a fabrication and never actually existed.

4. Fisher P-75 Eagle

At the outset of World War II, the United States had yet to develop the fighter planes that would eventually help them challenge the Luftwaffe. Most of these planes, such as the P-51 and P-47, were still being developed and hadn't yet reached their peak performance. As a result, the Luftwaffe typically had the upper hand in terms of aerial combat. In response, the United States Army Air Force sought a high-speed interceptor with heavy armament to combat the German air force.

Seizing the opportunity, the Allison Engine Company unveiled its new V-3420 engine—a massive 24-cylinder powerplant made by combining two V-1710 engines. Allison teamed up with the Fisher Body Division of General Motors to design a new airplane around this engine. Interestingly, Fisher opted to construct the P-75 using parts from existing successful aircraft. The P-75 was a hybrid, combining elements from the Dauntless dive bomber and various fighters, including the P-51 and P-40. The powerful engine was centrally located, driving two contra-rotating propellers via a drive shaft.

Naturally, it's no surprise that combining parts from existing airplanes to create a new fighter plane wasn’t effective. The P-75 was slow and unresponsive in its interceptor role, prompting the Air Force to reject the design. Fisher then attempted to market the P-75 as a long-range escort fighter for bombers. However, by the time this proposal was made, superior fighter planes were already available, leading Fisher to discontinue development of the P-75.

3. Northrop N-9M

In the 1930s and 1940s, renowned aircraft designer Jack Northrop dedicated himself to his vision of flying wing aircraft. Northrop aimed to build high-performance planes that eliminated the traditional fuselage, relying solely on a massive wing. At the onset of World War II, Northrop persuaded the United States Army Air Force to back his research into flying wings, hoping to develop a bomber with that design. They agreed to fund his efforts, so Northrop proceeded to construct a small test airplane to assess the viability of a flying wing bomber.

Known as the N-9M (with “M” standing for “model”), this aircraft was compact and lightweight. It had a distinctive boomerang shape and lacked vertical control surfaces. Its power came from two pusher propellers. The N-9M was initially challenging to fly, but once pilots adapted, it performed well. During testing, one fatal crash occurred, yet Northrop persisted. By the end of the war, he had gathered enough data to construct the flying wing bomber, the XB-35. Unfortunately, with the conclusion of the war, the Air Force lost interest in the bomber and its jet-powered variant, the YB-49. The project was ultimately shelved in the late 1940s.

Although the original flying wing bombers never materialized, the Air Force eventually adopted the B-2 stealth bomber years later. The design of the B-2 incorporated much of the research Northrop had conducted while working on the N-9M, making this World War II-era aircraft the precursor to the famous B-2. Today, one of the N-9M prototypes still flies, making appearances at air shows and other public events.

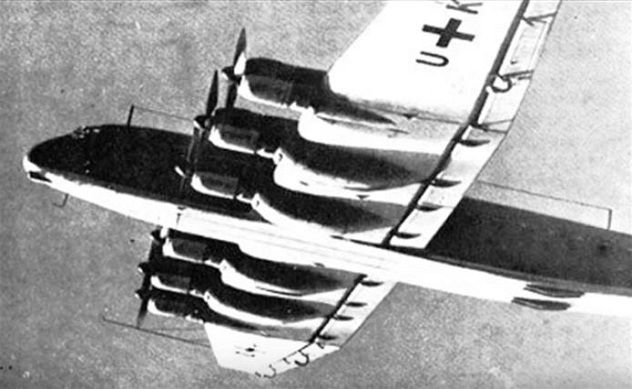

2. Junkers Ju 390

Unbeknownst to them at the time, the Luftwaffe made a grave mistake by neglecting the development of long-range heavy bombers. By the middle of the war, both the Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force had begun launching raids into German airspace, wreaking havoc on the German war industry. It was at this point that Luftwaffe commanders realized the urgent need for a heavy bomber, one that could reach the United States. This led to the creation of the 'America Bomber' project.

The Luftwaffe considered various designs for the project, with one of the most promising being the Junkers Ju 390. Developed by the German company Junkers, the new bomber was based on their existing Ju 290 heavy transport. The Ju 390 was equipped with six engines and had the capability of flying across the Atlantic. Test flights began in 1944, and results confirmed that the Ju 390 was a formidable and powerful aircraft. However, by this stage in the war, the Luftwaffe had already shifted to a defensive position, and any offensive bomber projects were given lower priority. Junkers managed to complete only two prototypes before the war ended.

The Ju 390's tests and operations have become surrounded by mystery and conspiracy. Some sources claim that one of the prototypes flew from Germany to South Africa during a test flight. Wartime reports also suggest that the bomber was flown over the Atlantic, entering U.S. airspace before turning back. Conspiracy theorists go further, speculating that a Ju 390 even flew to Argentina at the war's end, allegedly carrying secret weapons for Nazi escapees. Whatever the truth may be, the Ju 390 was the closest the Germans came to creating a bomber capable of reaching the United States.

1. Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1

During World War II, many nations explored the possibility of rocket-powered aircraft, with the German Me 163 Komet interceptor being the most famous. However, a lesser-known contender was the Soviet Union’s experimental rocket fighter, the BI-1.

In the late 1930s, Soviet leaders sought to develop a fast, short-range defense fighter powered by rocket engines. The urgency for such a plane intensified as German forces began their invasion of Russia. Engineers had designed the rocket plane by spring 1941, but Stalin initially withheld approval to build a prototype. However, when the German invasion began, Stalin gave the green light to engineers Alexander Bereznyak and Aleksei Isayev to expedite the project. Remarkably, they completed a working prototype in just 35 days. A bomber towed the BI-1 into the air, where it made its first glide test.

Rocket motor tests began in 1942, but powered flights quickly showed that the BI-1's flight time was limited to only 15 minutes after the pilot ignited the rocket. This major drawback severely hampered the fighter’s potential.

The engineers discovered a critical flaw when the third prototype disintegrated midair during level flight. It became clear that the frame, which was constructed from plywood and metal, wasn’t capable of withstanding the stresses of near-supersonic speeds. At the time, research into supersonic aerodynamics was still in its early stages, and the BI-1's airframe was not built to handle those speeds without falling apart. In essence, the BI-1’s speed was its own undoing. This discovery brought testing to a halt, and with the tide of the war turning in favor of the Soviets, no further development of defensive rocket planes took place.