During the early 1800s, a collection of original murals was uncovered in the former residence of the celebrated Spanish painter Francisco de Goya. Known as his Dark (or Black) Paintings, these works were predominantly created using somber and black hues, depicting eerie and unsettling themes. These pieces marked a stark departure from his usual Romantic style and his explorations of socio-political issues, which had cemented his legacy as 'the last of the Old Masters and the first of the Moderns.'

This distinctive series was found years after Goya’s passing, devoid of titles, dates, signatures, or explanations, leaving art historians to decipher the macabre and distorted imagery for generations. Despite being hailed as some of the most iconic artworks in history, many find the grim depictions too unsettling to view.

Summon your bravery to delve deeper into this series and the artist behind it with these 10 fascinating facts about one of the most chilling collections of art ever created: Goya’s Dark Paintings.

10. From Acclaimed Artist to Solitary Figure

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, widely known as Francisco de Goya, was born on March 30, 1746, in the small village of Fuendetodos. He died on April 16, 1828, at the age of 82. At just 14 years old, Goya began his artistic training in Spain and Italy, eventually establishing himself as a public painter in Zaragoza.

Goya eventually secured a position at the Royal Court, where he created portraits of Spanish aristocrats. The horrors of war, famine, and suffering he observed during the conflict between France and Spain deeply influenced his work, leading to some of his most renowned—and often contentious—paintings. These included nude works and pieces that sharply criticized the brutality of the Peninsula War.

Although Goya achieved early acclaim, his later years were marked by hardship. Disillusioned by the reinstatement of the Spanish monarchy under King Ferdinand III, he withdrew from society between 1820 and 1823. Living in seclusion, he battled declining health and deafness caused by an illness years earlier. It was during this period that he produced the fourteen murals now known as his Dark Paintings.

9. A Home with Somber Walls

Goya crafted his mysterious Dark Paintings within the walls of his villa, Quinta del Sordo (meaning House of the Deaf Man), located just outside Madrid. Interestingly, the villa was not named after him; its previous owner was also deaf. Goya painted the murals directly onto the villa’s walls, with some on the ground floor and others on the upper level.

Baron Èmiole d’Erlanger, who acquired Goya’s villa in 1873, carefully detached the murals from the walls and transferred them onto canvas for preservation. He later gifted these paintings to the state. Sadly, the removal process caused significant damage, necessitating extensive restoration efforts.

Goya’s murals were not created under commission or sponsorship, leading many to interpret them as his personal reflections. The artworks delve into religious and mythological themes, exploring concepts like death, aging, war, and malevolence, which further supports this interpretation.

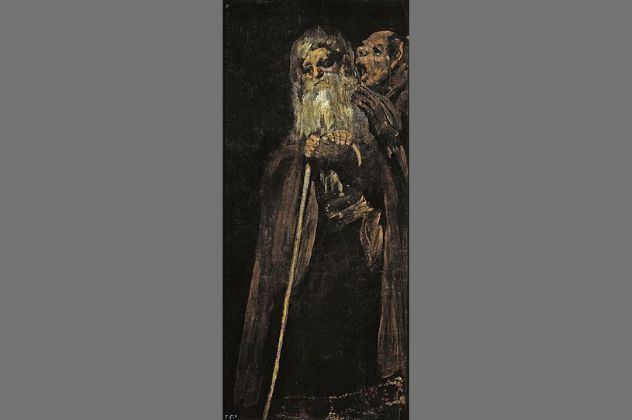

8. Two Old Men (or Two Monks)

One of Goya’s Dark Paintings, titled Two Old Men (or Two Monks), portrays a grotesque figure with an animalistic head seemingly yelling into the ear of an elderly man with a beard. The old man, leaning on a shepherd’s staff, displays a calm, contemplative expression. His resemblance to a figure in an earlier painting, believed to be a self-portrait, has led many to speculate that he represents Goya himself.

In the artwork, the man’s attire is believed to have religious significance. Meanwhile, the creature with a gaping mouth exhibits characteristics consistent with Goya’s portrayal of demonic figures in his other works, as noted by renowned art critic Robert Hughes. While both titles imply a similarity between the two figures, it is evident that a disturbing interaction is taking place. The exact nature of this interaction remains open to interpretation.

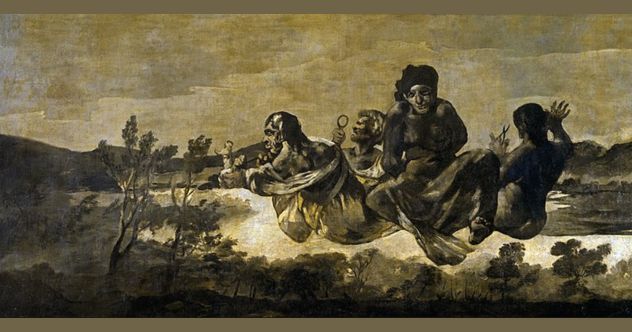

7. Atropos (The Fates)

Atropos (or The Fates) is likely inspired by the three Moirai from Greek mythology, who were responsible for determining the destiny of every human on Earth: the sisters Atropos, Clotho, and Lachesis. According to myth, Atropos wields the shears that cut the thread of life, deciding how each person dies. Clotho spins the thread, and Lachesis measures its length.

Goya’s depiction of the Fates is far more menacing and unsettling than traditional representations. Many interpret their monstrous appearance as a reflection of his own feelings about his harsh destiny. This theory is bolstered by the inclusion of a fourth figure at the center, who gazes outward at the viewer and appears bound by the thread.

It is speculated that this figure symbolizes human life as a powerless pawn of destiny, reflecting Goya’s own sense of entrapment due to his declining health and advancing age.

6. The Dog (or The Drowning Dog)

Described as 'the world’s most beautiful picture' by artist and writer Antonio Saura, The Dog (or The Drowning Dog) features one of the more subdued color palettes among Goya’s Dark Paintings. Only a small portion of the dog’s head is visible, with the rest of its body obscured by an undefined expanse of color.

The dog is set against negative space, seemingly gazing at something or someone outside the frame. In his book Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art, Fred Licht suggests that viewers must decide whether the dog is sinking in quicksand or if its body is concealed by a foreground slope.

Dogs are often symbolic of loyalty, and Licht suggests this association leads viewers to interpret the dog’s steady gaze as a sign of devotion. Given Goya’s well-documented love for dogs, this interpretation gains further weight. Some argue that The Dog critiques humanity’s despair in a godless world, while others see it as a meditation on the inevitability of death. The painting’s meaning, more than any other in the series, is deeply influenced by the viewer’s emotional state during their encounter with it.

5. Witches’ Sabbath (or The Great He-Goat)

In The Witches’ Sabbath (or The Great He-Goat), a towering, black-cloaked goat dominates the foreground, seemingly addressing a gathering of witches. The goat is widely interpreted as a representation of Satan. A lone figure in white stands apart from the group, leading many to believe the scene depicts the initiation of a new witch into the coven.

Many are surprised to discover that The Witches’ Sabbath is not intended as a literal depiction. Rather, the eerie, supernatural tableau serves as 'a satirical critique of what Goya perceived as the darker aspects of human nature and the moral decay of post-Napoleonic society.' Others interpret it as a condemnation of the growing influence of the church during Goya’s time at Quinta del Sordo.

4. Two Old Ones Eating Soup

Two Old Ones Eating Soup, also referred to as Two Witches, The Witchy Brew, or Two Old Men Eating, is the smallest painting in the series and was the best preserved. It is said to have been displayed on the ground floor of Goya’s villa.

In this painting, Goya depicts two grotesque figures seated at a table, eating. The figure on the right appears to have a skull for a head, leading many to associate the scene with death. Despite its decomposed state, the skeletal figure is shown 'devouring food voraciously, as if trying to consume everything possible.' Some experts interpret this imagery as a satirical commentary on greed or gluttony.

“Observe the expressions on the faces in these paintings,” says Manuela Mena, former deputy director for conservation and research at the Prado Museum. “Each one reflects a distinct personality. They’re not realistic; they’re caricatures, yet they reveal Goya’s profound fascination with human nature—our actions and motivations. In a way, he was like a writer, uncovering humanity’s flaws and mocking them through his art.”

3. Additional Works and Further Exploration

Other notable pieces in Goya’s Dark Paintings series include Asmodea (or Fantastic Vision), Fight with Cudgels (or The Strangers), Judith and Holofernes, La Leocadia, Men Reading, Procession of the Holy Office, Pilgrimage to San Isidro, and Women Laughing.

The collection captures a spectrum of intense emotions, including despair, isolation, sorrow, and occasional moments of laughter, though even these can feel unsettling. All fourteen paintings are housed in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid as part of a permanent exhibit, alongside other works by the artist. They can also be viewed online via the museum’s website. For further insights into Goya’s Dark Paintings, recommended videos by Can Özgar and Blind Dweller are available on YouTube.

2. Divergent Interpretations of the Dark Paintings

Goya’s enigmatic and symbol-rich Dark Paintings have been so extensively analyzed since their discovery that they risk being overinterpreted. Some scholars argue that the works reflect the artist’s troubled mental state, suggesting he was 'mad, melancholic, and pessimistic' during their creation. Conversely, others maintain that Goya remained an optimist with a sharp wit and a lucid mind until his final days.

Some theories even propose that the Dark Paintings were not created by Goya himself, but rather by his son, Javier, or grandson, Mariano, as a means to increase the villa’s sale value. Others speculate that artists like Juan José Junquera or Nigel Glendinning might have been responsible. However, most experts reject these claims, insisting that the works unmistakably bear 'Goya’s touch.'

1. Saturn Devouring One of His Sons (or Saturn Devouring His Son)

Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (or Saturn Devouring One of His Sons) portrays the Roman god Saturn consuming his own child. Saturn, associated with agriculture, time, and other attributes, originates from the Greek Titan Cronos. According to myth, Cronos feared a prophecy that he would be overthrown by his offspring, leading him to devour each child at birth. His wife, Rhea, saved their youngest, Zeus, by hiding him on Crete and tricking Cronos into swallowing a stone wrapped in cloth.

In the painting, Saturn kneels, gripping the lifeless body of his child with both hands. His mouth agape, he prepares to bite into the child’s arm. Saturn’s bulging, frenzied eyes are often interpreted as reflecting 'horror at his own savagery.' Scholars have debated whether this gruesome scene symbolizes 'the consuming nature of life in all its forms and death in all its brutality.'

Other analyses suggest that Saturn Devouring His Son may symbolize the darkness Goya encountered and endured throughout his life. Jay Scott Morgan’s article 'The Mystery of Goya’s Saturn' in the New England Review links the scene to Goya’s personal grief over the loss of his own children.

Goya and his wife, Josefa Bayeu, were parents to eight children, but heartbreakingly, seven of them died either in infancy or through miscarriage. A preliminary sketch from 1797 indicates that Goya had been contemplating this theme for several years before finally realizing it in his Dark Paintings.