Enacted in 1920, the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution remained in force until its repeal in December 1933. Prohibition was intended to rid American society of its alleged moral decay.

Contrary to the intent, Prohibition turned into a time of rampant drinking, gambling, and corruption. Most notably, it spurred inventive efforts to bypass the law across all sectors of society.

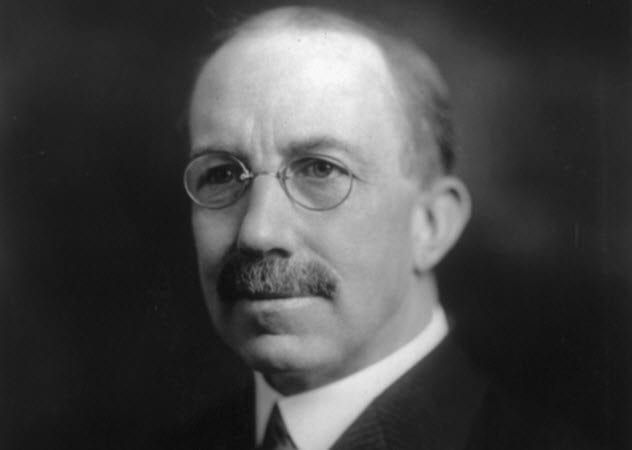

10. The 'Dry Boss' Who Advocated for the Implementation of Prohibition

Born in 1869 on a farm in eastern Ohio, Wayne Wheeler’s life took a dramatic turn after a farmworker, intoxicated, accidentally pierced his leg with a pitchfork. This traumatic event likely fueled his strong, almost religious, disdain for alcohol.

In 1894, Wheeler took on a full-time role with the Anti-Saloon League, where he quickly gained respect for his political strategy, dubbed 'Wheelerism.' Unlike other temperance movements, the League stayed focused on its sole mission—the total elimination of alcohol from American society.

The League strategically aligned itself with churches and either supported or opposed political candidates based solely on their stance toward Prohibition. Thanks to his significant influence, Wheeler earned the moniker of the 'dry boss.'

Wheeler was adamant about the strict enforcement of Prohibition. He also opposed using harmless substances like soap in denatured alcohol, favoring instead the inclusion of toxic chemicals, arguing that 'the person who drinks this industrial alcohol... is a deliberate suicide.'

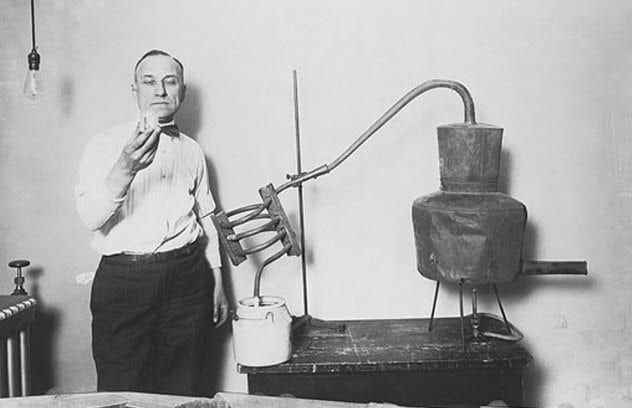

9. Prohibition Agents Earned Less Than Garbage Collectors

A contributing factor to the failure of Prohibition was the fact that many Prohibition agents were severely underpaid. In fact, most earned less than garbage collectors at the time.

In 1922, the national average income was $3,143, rising slightly to $3,227 in 1923. In contrast, the salary for most Prohibition agents ranged from $1,200 to $2,500, with 98% of the Prohibition Bureau earning within this range. By 1930, the starting salary for a Prohibition agent was $2,300, about two-thirds of the national average.

The Coast Guard’s pay was even lower. Coast Guard recruits made just $36 a month, which also included housing and free uniforms.

As expected, underpaid agents frequently resorted to accepting bribes from bootleggers and sometimes worked as chauffeurs for the very people they were supposed to be investigating. This led to the dismissal of over 10% of the agents from the Prohibition Bureau.

8. Bootleggers Wore ‘Cow Shoes’ to Conceal Their Tracks

In order to avoid detection by Prohibition agents, many bootleggers came up with clever methods to smuggle alcohol. One of the most bizarre innovations was the 'cow shoe,' designed to disguise footprints around hidden moonshine distilleries.

The 'cow shoe' was a metal strip attached to a wooden block carved to resemble a cow's hoof. When strapped to the foot, it left tracks similar to those of a cow, confusing agents and slowing their pursuit of criminal activity.

The concept of the 'cow shoe' is thought to have been inspired by a Sherlock Holmes story where the antagonist’s horse was outfitted with shoes that left prints resembling those of a cow’s hoof.

7. The Use of Wine for 'Sacramental Purposes' Increased

The Volstead Act, passed just before Prohibition took effect, authorized federal agents to investigate and prosecute those breaking Prohibition’s liquor laws. However, wines intended for religious purposes were exempt, allowing limited production of wine at home and in wineries.

To obtain sacramental wine, some individuals went so far as to pretend to be priests and rabbis. A 1925 study revealed that in just two years, the demand for sacramental wine in the US surged by 3 million liters (800,000 gallons).

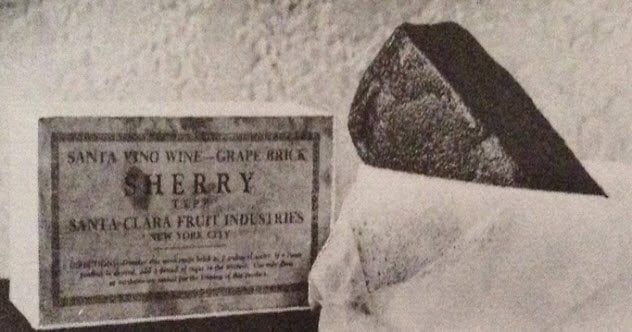

6. Wine Bricks Helped Save Many Vintners From Financial Ruin

Unable to make wine directly on their premises, many vintners began creating 'wine bricks,' solid blocks of concentrated grape juice. These bricks were targeted at home brewers who could dissolve them and make wine in the privacy of their own homes.

Because grape juice was not banned under Prohibition, the invention of wine bricks was a clever solution for vintners unwilling to destroy their vineyards. The law couldn’t do anything because the bricks came with warnings stating that they were for nonalcoholic use only.

The packaging for these wine bricks included instructions to dissolve the concentrate in 4 liters (1 gallon) of water. The instructions also cleverly 'warned' consumers not to leave the jug in a cool cupboard for 21 days, or it might turn into wine.

The makers of wine bricks also provided various flavors, like Burgundy or claret, that a person might experience if they 'accidentally' allowed the juice to ferment.

5. The 'Medical Beer' Movement Nearly Succeeded

In 1921, a coalition of brewers, doctors, and regular alcohol consumers attempted to persuade the US Congress that beer—a drink previously linked by temperance groups to idleness, neglected families, and unemployment—was, in fact, an essential medicinal remedy.

The so-called 'beer emergency' was widely recognized by both supporters and opponents as a broader debate on Prohibition. Proponents of beer argued for its relaxing properties and its nutritional benefits. One advocate even claimed that beer’s richness in vitamins had helped save the 'British race' from extinction during the plague years.

In a move that frustrated temperance advocates, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer declared that the 'beverage' clause of the 18th Amendment permitted doctors to prescribe beer at any time, for any reason, and in any quantity deemed necessary.

However, just months after Palmer's ruling, Congress took up the beer emergency bill and passed a law that completely prohibited beer. By the close of 1921, the bill had been enacted, much to the disappointment of passionate beer supporters.

4. Prohibition Officials Were Often Found Drinking Alcohol Themselves

Some officials enforcing Prohibition were guilty of breaking the very laws they were tasked with upholding. One notable example is Colonel Ned Green, the Prohibition administrator in San Francisco, who was suspended from his post in 1926 after Alf Oftedal, the assistant commissioner in charge of enforcement, caught Green serving confiscated alcohol at private gatherings.

Green later joked to reporters that his suspension had been long overdue. In the aftermath of his scandal, all future administrators were required to sign a pledge of abstinence.

Prohibition officers were also complicit in assisting bootleggers with accessing whiskey from bonded warehouses. In one case, two administrators were accused of issuing permits that allowed $1 million worth of alcohol to be withdrawn in a single day.

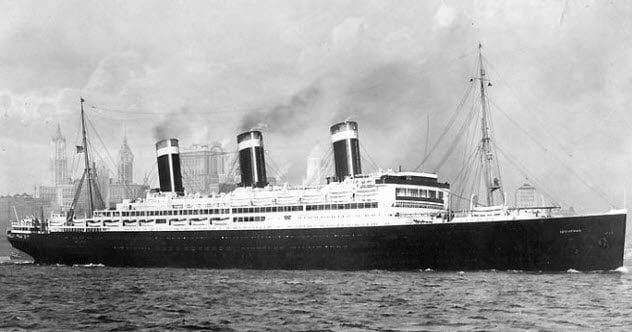

3. ‘Cruises To Nowhere’ Became A Trend

During Prohibition, the law allowed drinking alcohol outside of the United States' 5-kilometer (3 mi) territorial limit. This led to the rise of 'booze cruises' or 'cruises to nowhere.' As the name implies, these were short voyages without any specific destination where passengers could freely indulge in alcohol.

Famous ships such as the Berengaria and Aquitania from Cunard, the Majestic from White Star, and the Leviathan from United States Lines all provided these excursions. Some were brief weekend getaways into the Atlantic, while others included stops in Nova Scotia or Bermuda.

Quick sailing trips to the Bahamas and Havana also gained popularity. These destinations saw the rise of clubs and bars catering to the thirsty American tourists.

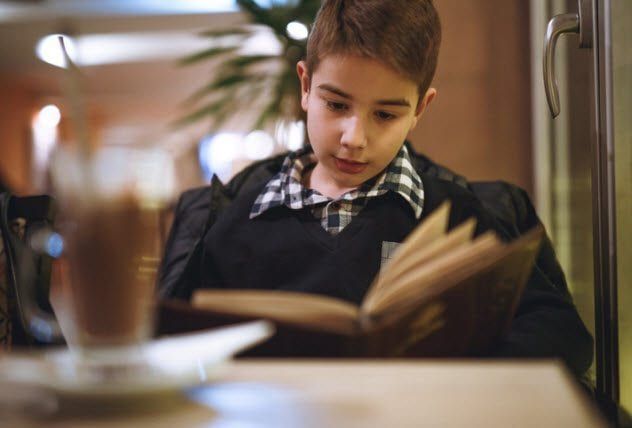

2. The Inception of Children’s Menus Happened During Prohibition

Before Prohibition, dining out was a rare treat for children. Only those from affluent families and staying at hotels could afford to eat at restaurants. Establishments not attached to hotels typically refused service to children as they were seen as a distraction from the adult enjoyment of alcohol.

When Prohibition was enacted, restaurant and hospitality business owners quickly realized that children could become a new source of revenue to compensate for the lost profits from liquor sales.

In 1921, the Waldorf Astoria in New York led the way by introducing the first children's menu. This innovation was quickly adopted by other eateries. However, this also meant a new restriction: children were no longer allowed to eat the same dishes as their parents in these establishments.

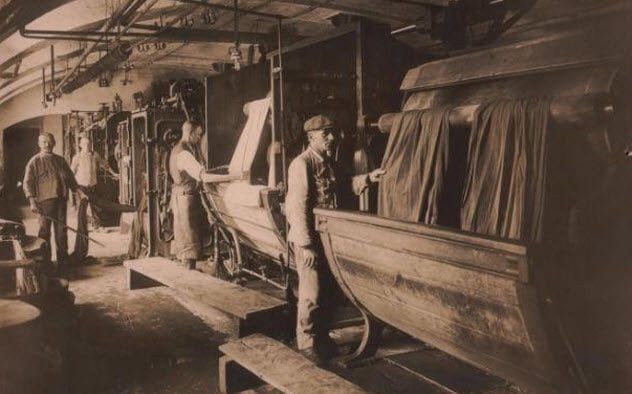

1. Breweries Came Up with Creative Solutions to Stay in Business

By the time World War I ended, the nation was already edging closer to a full prohibition on alcohol. Breweries were limited to producing beer with a maximum alcohol content of 2.75 percent, commonly referred to as 'near beer.' When Prohibition was enacted, this limit was further reduced to just 0.5 percent.

Not all brewers were satisfied with producing 'near beer.' Companies like F.M. Schaefer Brewing Company and Nuyens Liquers opted to produce dyes instead. This move proved profitable due to the shortage of dye in the country and the ability to repurpose their brewing equipment. Interestingly, some of these dye factories also recognized the similarities in production processes and began secretly making illegal alcohol.

Other brewers, including Schlitz, Miller, and Pabst, shifted to producing malt extract, marketing it as a cooking ingredient. However, its true purpose was clear to many: people bought it to make their own beer, or 'home brew.'

Meanwhile, brewers like Anheuser-Busch and Yuengling turned their efforts toward producing ice cream.