Today, we view slavery as one of the most contentious and unethical practices in history. It is seen as a cruel, immoral, and unacceptable trade where human lives were treated as commodities. In contrast, for the people of ancient Rome, slavery was an integral part of their daily lives, fully embedded into the social order.

Presented below are 10 captivating facts about slavery in ancient Rome, featuring several firsthand accounts that allow us to hear directly from the ancients regarding this controversial topic.

10. The Size of the Slave Population

In Ancient Rome, slaves made up a significant portion of the population. Some estimates suggest that by the close of the first century BC, as much as 90 percent of the free population in Italy could trace their ancestry back to enslaved individuals (McKeown 2013: 115).

The number of slaves was so substantial that some Roman lawmakers expressed concern over the potential risks of this imbalance. As Seneca wrote in *On Mercy*: “It was once proposed in the Senate that slaves should be distinguished from free people by their dress, but then it was realized how great a danger this would be, if our slaves began to count us” [Seneca, On Mercy: 1.24].

Modern estimates suggest the slave population in Italy reached approximately 2 million by the end of the Republican era, with a slave-to-free ratio of about 1:3 (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 736).

9. Slave Uprisings

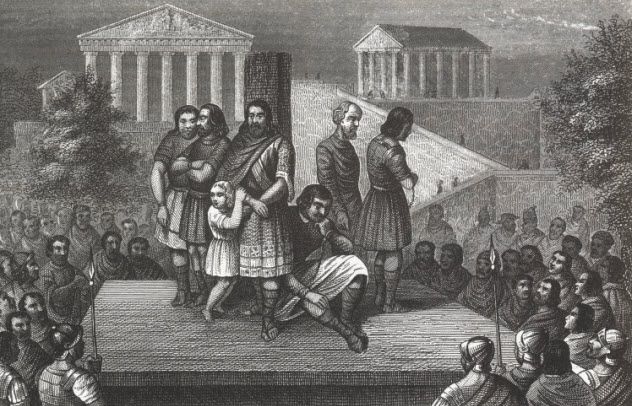

Numerous slave uprisings are documented throughout Roman history. One such revolt occurred in Sicily between 135 and 132 BC, led by a Syrian slave named Eunus. Eunus portrayed himself as a prophet and claimed to have received various mystical visions.

As reported by Diodorus Siculus in *The Library* (35.2), Eunus managed to convince his followers with a trick that made sparks and flames appear from his mouth. Although the Romans ultimately defeated Eunus and suppressed the rebellion, this event may have inspired another slave revolt in Sicily between 104 and 103 BC.

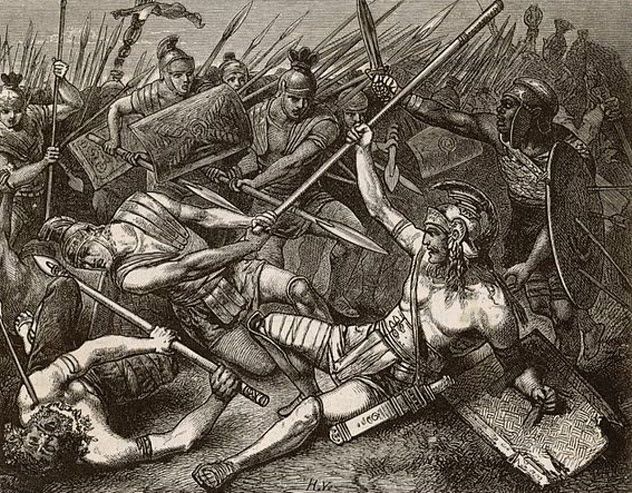

The most renowned slave uprising in ancient Rome was the one led by Spartacus. The Roman military fought against Spartacus’s forces for two years (73–71 BC) before the rebellion was finally quelled.

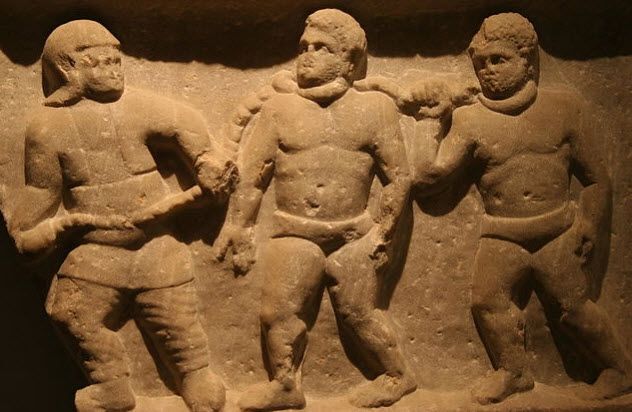

8. Varied Lifestyles

The living conditions and expectations for slaves in ancient Rome varied widely, largely depending on their work. Those involved in backbreaking labor, like agriculture or mining, faced grim futures. In particular, mining was known for being a brutal and dangerous occupation.

Pliny [Natural History 33.70] describes the grueling nature of this work: “Mountains are hollowed out by the digging of long tunnels by the light of torches. The miners work in shifts as long as the torches last and do not see daylight for months at a time. [ . . .] Sudden cracks appear and crush the miners so that it now seems less perilous to dive for pearls and purple mollusks in the depths of the sea. We have made dry land so much more dangerous!”

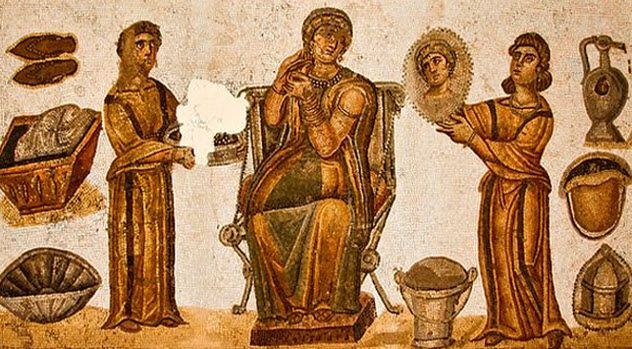

In contrast, household slaves often received more humane treatment, and in some instances, they were permitted to manage small amounts of money and even personal property. This property, known as 'peculium,' was technically owned by the master, but slaves were allowed to use it for their own needs and desires.

Over time, if a slave accumulated enough wealth, they might have the opportunity to purchase their freedom and join the ranks of the 'freedmen.' This social group occupied a middle ground between slaves and full-fledged citizens. As a freedman, they would still remain legally bound to their former master's household.

7. Who Was the Most Notable Roman Slave?

Spartacus, a Roman slave originally from Thrace, is arguably the most famous slave in Roman history. In 73 BC, he escaped from a gladiatorial training facility in Capua, bringing along about 78 other slaves. Spartacus and his followers capitalized on the deep social inequalities of Rome, amassing thousands of slaves and impoverished rural folk to join their cause.

For two years, Spartacus and his forces boldly resisted the might of the Roman authorities and military. As noted by Frontinus [Stratagems: 1.5.22], Spartacus's army used the strategy of placing dead bodies on stakes, armed with weapons, around their camp. This created the illusion of a much larger and better-equipped army than they actually had.

The uprising was ultimately quelled by the Roman General Crassus. Spartacus was slain, but his name and heroic actions lived on in the collective memory of Rome. His legacy remains immortal, inspiring countless books, TV shows, and films. Following their defeat, more than 6,000 slaves involved in the revolt were crucified along the Via Appia, the road connecting Rome and Capua.

6. Ownership of Slaves

Slavery was a widespread practice in ancient Rome, embraced by citizens from all walks of life, regardless of social standing. Even the poorest Romans could own one or two slaves. In Roman Egypt, it was common for artisans to have around two or three slaves. The wealthier citizens could own far more. For example, Nero is known to have had around 400 slaves working at his urban residence. Additionally, a wealthy Roman named Gaius Caecilius Isidorus was recorded to have 4,166 slaves when he passed away (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 736).

5. The Demand for Slaves

The demand for slaves in Rome was driven by several factors. Slaves were integrated into nearly every facet of Roman life, with the exception of public office. Labor-intensive sectors like mining and other exploitative industries had a particularly high demand for slaves to fulfill the grueling tasks.

Domestic work and agricultural labor were two fields where slaves were in great demand. In fact, the management of slaves is discussed in many surviving Roman guides on farming. In his work *On Farming*, Varro advises that free labor should be employed in unhealthy environments. The reasoning behind this suggestion is that, unlike free farmers, the death of slaves leads to a negative financial outcome (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 736).

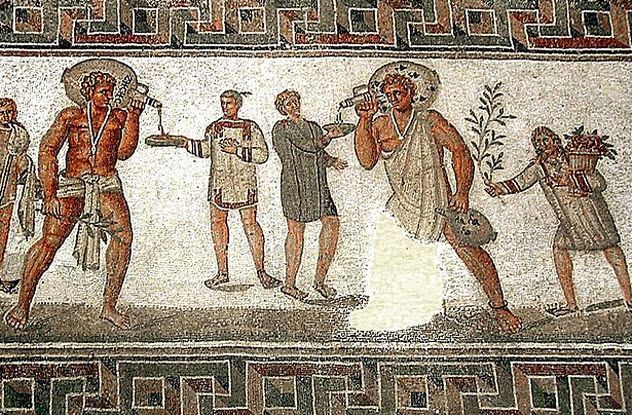

4. Slave Acquisition

Slaves were obtained through four primary methods: as prisoners of war, as victims of pirate raids or banditry, via trade, or through breeding. Depending on the period in Roman history, some of these methods were more prevalent than others. For instance, during the early phases of the Roman Empire’s expansion, a significant number of slaves were captured during wars.

The pirates from Cilicia, located in what is now southern Turkey, were skilled in supplying slaves, and the Romans had extensive trade relations with them. These pirates typically brought their captives to Delos, an island in the Aegean Sea, which was regarded as the global hub of the slave market.

Historical accounts state that on one occasion, more than 10,000 individuals were sold as slaves and transported to Italy within a single day. This suggests that the line between piracy and trade was often blurred when it came to acquiring slaves.

3. Emancipation of Slaves

In Roman society, a slave owner had the right to free their slaves, a process known as manumission. This could happen in various ways: the owner might grant freedom as a reward for the slave's loyalty and services, the slave could earn it by paying the master a certain sum to buy their freedom, or the master might free the slave for practical reasons.

An instance of this scenario is when merchants needed someone legally authorized to sign contracts and manage transactions on their behalf, as slaves were not permitted to represent their owners in legal matters.

At times, a slave's freedom could be fully granted, while in other situations, the former slave would still owe services to their previous master. Slaves who were skilled in a trade often had to provide their expertise without payment to their former masters. In some cases, these freed individuals might even become Roman citizens or, ironically, slave owners themselves.

Cristian has been consistently contributing articles to both digital and print media. His work can be found in publications such as Ancient Warfare Magazine and Ancient History Magazine.

2. Fugitive Slaves

Slave escapes from their masters were a frequent issue for slave owners. To address this, they often hired professional slave catchers called fugitivarii, who would track down, capture, and return the escaped slaves to their owners for a fee. In some cases, owners would offer public rewards for the return of their runaways, while in others, they would search for the fugitives themselves (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 736-737).

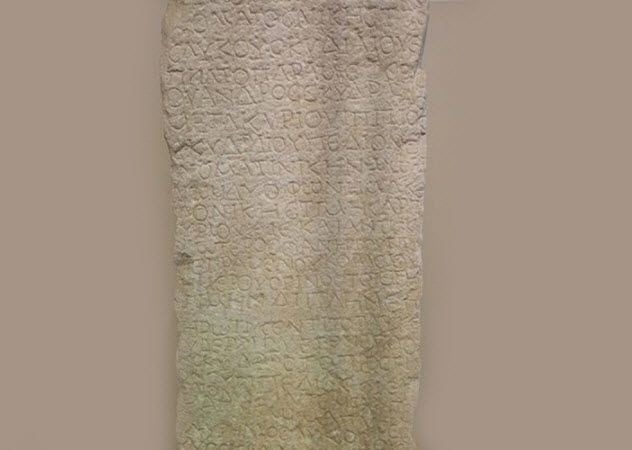

Another interesting tactic used to deal with runaway slaves was the use of slave collars inscribed with instructions on where to return the slave. One such example reads as follows:

I am Asellus, slave of Praeiectus, an official in the Department of the Grain Supply. I have escaped from my duties. Detain me, for I have run away. Take me back to the barber’s shops near the temple of Flora [Select Latin Inscriptions 8272] (McKeown 2013: 116).

1. An Unquestioned Institution

Slavery is often viewed as an immoral and inhumane practice. However, there is little evidence to suggest that slavery was seriously challenged in Roman society. The economic, social, and legal structures of ancient Rome all worked together to ensure the continuation of slavery as an institution.

Slaves were regarded as the antithesis of free individuals, serving as a necessary counterbalance in society. Civic freedom and slavery were seen as two opposing but complementary forces. Even though some more compassionate laws were introduced to improve the living conditions of slaves, these changes did little to diminish the prevalence of slavery. They merely made the institution more bearable (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 736-737).