Easter Island, home to 887 colossal moai statues, has transformed from one of the planet's most secluded spots to a globally renowned and enigmatic destination. Each year, new theories emerge about the island, its statues, and the ancient Rapa Nui civilization. Below are some of the most captivating ideas.

10. The Moai Were Moved Upright

One of the most debated topics is how the massive moai statues were transported to their current locations. The tallest statue, 'Paro,' measures nearly 10 meters (33 ft) in height and weighs a staggering 74 metric tons (82 tons). Moving such enormous figures would have been an extraordinary challenge.

In the early 1980s, researchers attempted to replicate and relocate some statues using only tools available to the islanders. They found the task nearly insurmountable. However, in 1987, archaeologist Charles Love successfully moved a 9-metric ton (10 ton) replica. Using a makeshift sled system, he and a team of 25 men rolled the statue 46 meters (150 ft) in just two minutes.

A decade after this achievement, Czech engineer Pavel Pavel and Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl constructed a statue of identical proportions. They secured one rope around its head and another at its base. With a team of 16 individuals, they swayed the statue back and forth. The experiment was halted prematurely due to potential damage to the statue, but Heyerdahl calculated that they could have moved the statue (or one twice its size) approximately 100 meters (330 ft) daily.

Recently, researchers Terry Hunt and Carl P. Lipo explored the intriguing hypothesis that the Rapa Nui people used ropes to maneuver the massive moai statues into position with a walking motion. Their team successfully moved a replica 100 meters (330 ft) using this method. They also suggest that this aligns with Rapa Nui legends, which describe the statues as walking through magical means.

9. Ecocide

A widely accepted theory suggests that the island's inhabitants deforested vast areas for farming, mistakenly believing the trees would regenerate quickly enough to maintain ecological balance. The increasing population exacerbated the issue, leading to the island's eventual inability to sustain its people. This idea gained prominence through Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed by UCLA geographer Jared Diamond, who cites Easter Island as a prime example of societal collapse due to resource mismanagement.

However, recent research challenges this narrative, arguing there is scant evidence to support it. Instead, the Rapa Nui people are now recognized as highly skilled agricultural engineers. Detailed studies reveal they intentionally enriched their farmland using volcanic rock for fertilization.

Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo, in their ongoing research on Easter Island, propose that while the islanders cleared much of the forest, they replaced it with grasslands. They argue against the idea of a self-induced disaster causing the islanders' decline. Anthropologist Mara Mulrooney supports their findings, with radiocarbon data indicating the island was inhabited for centuries, with population decline occurring only after European contact.

8. The Rats Were Responsible

Lipo and Hunt propose a different theory for the population decline. With no natural predators and abundant food, rats stowed away in the canoes of the island's first settlers thrived unchecked. While the islanders cleared and burned trees, the rats hindered regrowth by consuming young plants.

Although rats damaged the island's ecosystem, they also became a new food source for the inhabitants. Rat bones found in ancient garbage piles suggest the islanders ate the rodents, providing sustenance as they developed agricultural systems for long-term survival.

7. Alien Assistance

A whimsical yet popular theory suggests that the massive moai statues on Easter Island were either created or influenced by extraterrestrial beings.

Erich von Daniken popularized this theory in his book Chariots of the Gods?: Unsolved Mysteries of the Past. He argues that the ancient Egyptians lacked the knowledge and physical capability to construct the pyramids unaided. Similar ideas have been applied to the Mayan pyramids and the Nazca lines.

The stone for the moai was sourced from an extinct volcano on the island's northeastern side, not from extraterrestrial origins. There is no doubt about who created the statues; the true enigma lies in their purpose. Many researchers speculate that each statue symbolizes the head of a family, though this remains unproven.

6. The Road Less Traveled

In 2010, archaeologists refuted a long-standing theory from 1958, proposed by Thor Heyerdahl, about how the moai were transported across the island. Heyerdahl claimed the ancient roads were the primary routes for moving the statues, citing fallen moai found near these paths as evidence of abandonment during transit.

Heyerdahl challenged British archaeologist Katherine Routledge’s 1914 hypothesis that the roads served ceremonial purposes. Recent findings support Routledge’s theory, revealing the roads were concave, making it highly impractical to transport heavy statues. The fallen moai likely toppled over time from their original positions.

The archaeological team observed that all roads lead to the extinct volcano Rano Raraku, suggesting it was considered the island’s sacred center or focal point.

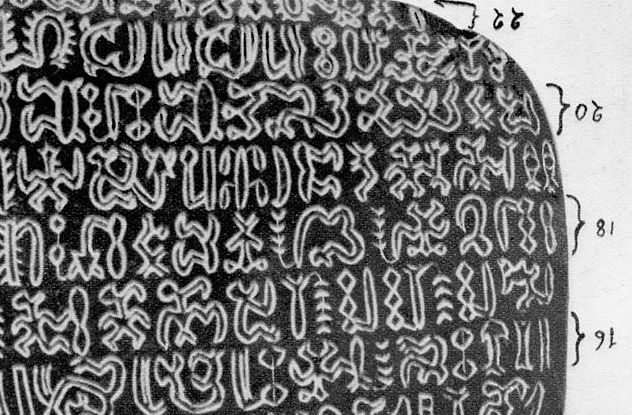

5. The Writing System

In a controversial theory, Robert M. Schoch proposed in 2012 that Easter Island’s writing system is 10,000 years older than commonly accepted, suggesting the island itself is also far more ancient than previously believed.

Schoch developed this idea after studying Gobekli Tepe, an ancient stone site in Turkey dated to 12,000 years ago. The absence of evidence for settlement or agriculture implies the site was used exclusively for ceremonial purposes.

Schoch also challenges the established timeline of the Giza Sphinx, claiming it was constructed between 5000 and 7000 B.C. This assertion lacks supporting evidence, as no civilization is known to have existed in Giza during that period. Schoch argues that both Gobekli Tepe and the Sphinx were creations of hunter-gatherer societies.

Schoch draws parallels between the Gobekli Tepe pillars and Easter Island’s moai, citing similarities in artistic style and hand depictions. However, he overlooks the 12,000-year gap between the two sites and the stark differences in size and form—Easter Island’s statues are massive with prominent heads, while the Turkish figures are slender and lack distinct heads.

Schoch also theorizes that the rongo rongo script of Easter Island might document a celestial plasma event occurring thousands of years ago. In modern terms, plasma phenomena include thunderstorms, lightning, and auroras.

4. Long Ears vs Short Ears

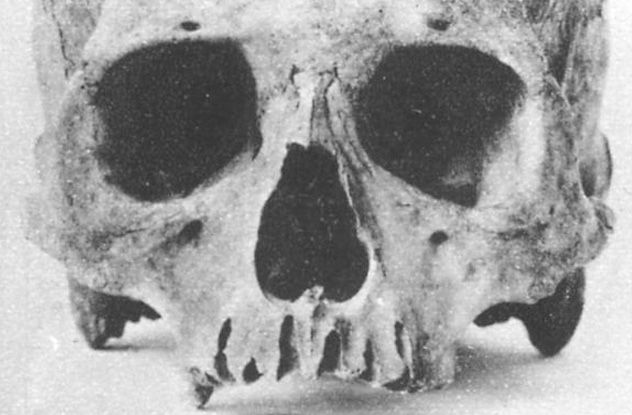

Rupert Ivan Murrill, in his work Cranial and Postcranial Skeletal Remains from Easter Island, notes that skulls discovered on the island were elongated and narrow, with evidence of long ears. Thor Heyerdahl’s Aku-Aku recounts a violent conflict between the short-eared and long-eared inhabitants of Easter Island.

According to legend, the long-eared inhabitants, who were the island's first settlers, dug a trench around 1675 and filled it with dry brushwood. A long-eared man confided in his short-eared wife about his people’s plan to lure the short-ears into the trench and set them ablaze. Horrified, the wife revealed the plot to her people, betraying her husband to protect them.

A violent confrontation ensued, with the short-eared group driving the long-eared people into the trench and setting it on fire, killing men, women, and children. Only two long-eared individuals escaped to a nearby cave. The short-ears pursued them, killing one and leaving a single survivor.

Heyerdahl identified the long-ears as Peruvians, suggesting they predated the Polynesian short-ears. However, Captain James Cook, who visited Easter Island between 1772 and 1775, observed many individuals with elongated earlobes, casting doubt on the accuracy of this narrative.

3. Tukuturi

Tukuturi is a moai statue depicted in a seated or kneeling posture, believed to symbolize an ancient singer. Its posture mirrors that of individuals participating in the rui festival. The statue’s head is tilted higher than others, and it features a distinctive beard.

Tukuturi is significantly smaller than other moai statues, with more human-like facial features. Unlike the others, it was crafted from red Puna Pua stone. Its gaze toward Orongo has led to theories linking it to the Birdman cult.

Another hypothesis suggests Tukuturi may represent an experiment with new sculpting methods. The statue’s legs, knees, and buttocks are intricately detailed, and its kneeling posture is interpreted as a sign of watchfulness and endurance. Discovered in the 1950s, Tukuturi remains one of the island’s most fascinating statues.

2. The Birdman Cult

The Rano Kau crater, home to Orongo village, hosted a competition to honor the fertility deity Makemake. Participants had to descend the crater’s steep slopes, swim through shark-infested waters, and retrieve an intact egg from a nearby islet. The victor, known as Birdman, assumed leadership for the year. This cult dominated the island’s religious practices until 1867.

During the Birdman era, the islanders sought to revive their society and reclaim their former strength. However, they were devastated by disease and injuries, leaving them unable to recover. Missionaries arrived during this vulnerable period, converting the islanders to Christianity and eradicating traditional clothing, tattoos, body art, and cultural artifacts like rongo rongo tablets.

Eventually, the Rapa Nui people were confined to a small portion of the island, with the rest used for ranching. Today, few individuals maintain direct connections to the original Rapa Nui heritage.

1. The Stone Bodies

During excavations in 2011, scientists discovered that the iconic moai heads on Easter Island are connected to massive stone bodies buried underground. Decades earlier, Heyerdahl had unearthed one such statue, but the new findings revealed statues reaching 7 meters (23 ft) in height. The torsos feature intricate, undeciphered petroglyphs.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg, the project director, uncovered additional fascinating details, including ropes tied to a tree trunk in a deep pit. She theorizes that the Rapa Nui people used ropes and the trunk to erect the statues. Petroglyphs were carved into the front before raising and into the back afterward.

Another intriguing find was red pigment in a burial pit. Van Tilburg asserts that the islanders used this pigment to paint the moai, much like they adorned themselves for rituals. She also suggests that human bones found nearby imply burials occurred around the statues, with the red pigment playing a role in ancient funerary customs.