Over 6,000 languages are spoken worldwide. In many areas, frequent interactions occur among speakers of different languages, from sporadic trade to communities where multiple languages are spoken. Islands, however, act as natural barriers, isolating populations and leading to fascinating linguistic outcomes. On remote islands, languages can evolve unique characteristics or retain ancient traits absent in other contemporary languages.

10. Pukapuka

Pukapuka, the most isolated part of the Cook Islands, is incredibly small, covering just around 3 square kilometers (1 square mile) of land. Despite its size, a unique language called Pukapukan has emerged there. It is classified as a separate branch within the Polynesian group of Austronesian languages, and its connections to other languages remain uncertain.

Pukapukan shares similarities with other Cook Islands languages but also exhibits traits found in languages from eastern islands like Samoan and Tuvalu. Similar to many Polynesian languages, Pukapukan differentiates between short and long vowels. For instance, Tutu means “burn,” tutuu means “lower a bunch of coconuts,” tuutu means “suit of clothes,” and tuutuu means “picture.”

Pukapukan has just four color terms, all seemingly derived from words for talo root, a staple food. The inner layers of talo roots vary in color. Ina describes white roots and light shades. Uli refers to dark roots and colors. Kula roots are rose-colored. The fourth term, yengayenga, encompasses blue, yellow, and their combinations, possibly originating from a word describing the inside of a raw talo tuber.

9. Haida Gwaii

Haida Gwaii, previously referred to as the Queen Charlotte Islands, lies off the coast of British Columbia, Canada. The indigenous language of the region, Haida, is critically endangered, with only about 20 fluent speakers left.

Haida's phonetic system includes around 30 consonant sounds and 7–10 vowel sounds. The precise count varies by dialect—remarkably, even with just 20 speakers, distinct dialects exist, differing enough to be considered separate languages.

A striking feature of Haida's consonant system is the use of ejectives. For instance, Haida has both a plain /t/ and an ejective /t’/. The plain /t/ resembles the English /t/, where the tongue touches the roof of the mouth just behind the teeth, briefly blocking airflow. The ejective /t’/ is formed similarly, but the larynx is raised, compressing air in the mouth before release, creating a distinctive popping sound.

Debates over how to classify Haida have persisted for over a century. In 1915, Edward Sapir proposed the Na-Dene language family, which included Haida, Athabaskan languages, and Tlingit. Evidence supporting this connection includes shared vocabulary and similarities in verb prefix structures. However, many linguists now argue that the evidence is insufficient, often classifying Haida as a language isolate.

8. Hawaii

The Hawaiian Islands are geographically remote, situated approximately 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) from the mainland United States. Hawaiian is the sole indigenous language native to these islands.

Hawaiian belongs to the Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. It features a minimal sound system, with just eight consonants: /p/, /k/, /ʔ/, /m/, /n/, /h/, /l/, and /w/. Hawaiian also enforces strict syllable formation rules. Syllables can only consist of a vowel or a consonant followed by a vowel, making complex English words like “sticks” impossible. This limitation, combined with the small consonant set, results in lengthy Hawaiian words. For example, the name Janice “Lokelani” Keihanaikukauakahihulihe’ekahaunaele was too long to fit on a driver’s license.

Hawaiian has been influenced by English due to prolonged contact between speakers. Many English words have been adapted into Hawaiian, undergoing significant changes to align with its phonetic system. For instance, English /t/ becomes Hawaiian /k/, as in “ticket” transforming into “kikiki.” The popular Hawaiian Christmas greeting “Mele Kalikimaka” originated from English “Merry Christmas,” with /r/ becoming /l/, /s/ becoming /k/, and vowels inserted between consecutive consonants.

7. Iceland

Iceland was first settled by Norwegian Vikings in the late 870s. The language spoken at the time was a form of Old Norse. Modern Icelandic has evolved from this language and retains many of its ancient characteristics.

For example, Icelandic maintains a case system with four cases: nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive. These cases have distinct forms for each of the three genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and for both singular and plural. Nouns are also divided into “strong” and “weak” classes, each with its own grammatical rules.

Icelandic boasts a rich written history, with preserved texts dating back to 1100 AD. Its alphabet, based on Latin characters, resembles English but includes unique letters such as accented vowels, þ (“thorn”), and ð (“eth”). These letters represent sounds found in English, with þ corresponding to the “th” in “with” and ð to the “th” in “whether.” These characters were once used in Old English and other Germanic languages but have since disappeared.

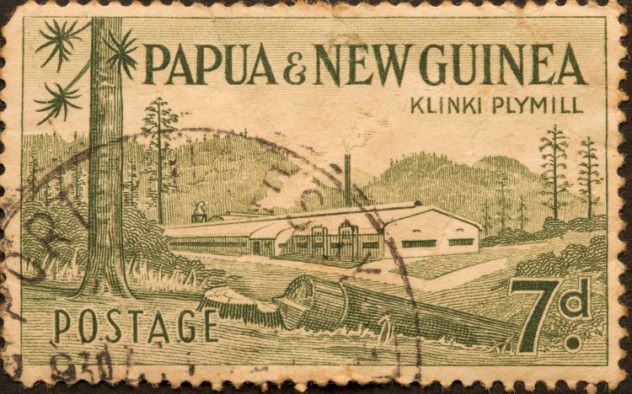

6. New Guinea

New Guinea is politically divided, with Papua New Guinea occupying the eastern half and Indonesia controlling the west. The island is renowned for its cultural and linguistic diversity, with Papua New Guinea alone home to over 800 languages.

Despite this immense diversity (or possibly because of it), these languages remain poorly documented. Little is known about their connections to each other or to languages on nearby islands. A notable feature of Papuan languages is the use of noun classifiers, which are words or affixes paired with nouns to specify their type.

For example, Imonda uses classifiers for edible greens, breakable items, and clothing or flat objects. Motuna employs 51 noun classifiers, including categories for small limbs, root vegetables, hard-shelled nuts, and objects wrapped lengthwise. Teiwa has three classifiers for fruit: one for round fruits like coconuts, one for cylindrical fruits like cassava roots, and one for elongated fruits like bananas.

5. Jeju Island

Located off the southern coast of Korea, Jeju Island is a well-known tourist spot. Its culture is unique compared to mainland Korea, featuring iconic stone statues called hareubang. The local language, Jejueo, is often considered a Korean dialect, but its significant differences have led linguists to classify Jejueo as a separate language.

This classification has been scientifically validated. Dialects are typically mutually intelligible, but when speakers of three mainland Korean dialects listened to a 75-second Jejueo story and answered comprehension questions in Standard Korean, their accuracy ranged from 5–12 percent. This low comprehension rate confirms that Jejueo is not intelligible to Korean speakers, solidifying its status as a distinct language.

4. Malta

Malta, an island country in the Mediterranean south of Italy, has Maltese as its native language. Maltese is one of the nation's official languages, alongside English, and is part of the Semitic family, which includes Arabic and Hebrew. It is the only Semitic language recognized as an official language of the European Union.

Maltese evolved from a form of Arabic known as Siculo-Arabic, once spoken in Sicily. Settlers brought this language to Malta in the 11th century. By the mid-13th century, European conflicts led to the expulsion of Muslims, isolating Siculo-Arabic speakers from other Arabic-speaking communities. While Arabic was replaced by Sicilian in Sicily, it persisted alongside Italian in Malta, evolving into a unique language. Today, about half of Maltese vocabulary is derived from Italian.

3. Australia

Australia is home to hundreds of Aboriginal languages, and like those in New Guinea, their relationships remain unclear. However, Australian languages are distinguished by several unique features, particularly their absence of fricatives—sounds like those in “fish” made by partially obstructing airflow. While most global languages include at least one fricative, Australian languages largely lack them. They are also known for their abundance of lateral sounds, similar to the English /l/. When listening, the absence of /s/, /z/, or other fricatives is striking.

In many Australian Aboriginal cultures, there are strict rules governing interactions among family members. Everyday language is not suitable for all interactions, and specific family relationships require the use of a specialized “avoidance style” of speech. This style shares the same grammar and pronunciation as regular speech but uses an entirely distinct vocabulary. The rules for avoidance speech differ across cultures, but it often applies to in-laws, who may be prohibited from direct communication. For instance, a man might be forbidden from using certain words in his mother-in-law's presence. Avoidance speech tends to be more general, consolidating multiple terms into one. For example, in Bunuba, specific boomerang types like balijarrangi, gali (returning boomerangs), and mandi (non-returning boomerangs) are replaced with the generic term jalimanggurru in avoidance speech.

2. Madagascar

Madagascar, a large island off southern Africa, is home to the Malagasy language. Despite its proximity to Africa, Malagasy is unrelated to African languages. Instead, it belongs to the Austronesian language family, with its closest relatives spoken in Indonesia, 7,500 kilometers (4,700 miles) away.

Early Portuguese sailors in the 1600s observed similarities between Malagasy and Austronesian languages. Since the 1950s, more detailed research has confirmed Malagasy’s Austronesian roots. One way to illustrate this connection is through vocabulary comparisons. For example, Malagasy number words resemble those in Javanese and Ilocano (spoken in Indonesia and the Philippines) but differ significantly from nearby African Bantu languages like Swahili and Tsonga. Here are the words for numbers one through five:

Malagasy: iray, roa, telo, efatra, dimy

Ilocano: esa, dua, telu, empat, delima Javanese: siji, loro, telu, papat, lima

Tsonga: n’we, mbirhi, nharhu, mune, ntlanu Swahili: moja, mbili, tatu, nne, tano

1. North Sentinel Island

North Sentinel Island, part of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, is home to the Sentinelese. These indigenous people remain largely unknown due to their long history of hostility toward outsiders. Limited observations and photographs indicate that the Sentinelese live in a Stone Age-like society, with the only metal they possess being salvaged from shipwrecks.

Following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, the Indian government dispatched helicopters to assess the island's survival. The Sentinelese responded by attacking the helicopters, and an image of a man throwing a spear at a helicopter gained global attention. As a result, the Sentinelese language remains entirely unknown. Linguists speculate, based on limited evidence, that it may belong to the Andamanese language family spoken on neighboring islands.