The term “mummy” often brings to mind vivid imagery. Many envision the preserved rulers of ancient Egypt, carefully wrapped in linen and prepared for their eternal journey. The iconic death mask of Tutankhamun might come to mind, or perhaps the haunting Andean child mummies, which appear as though they could awaken at any moment.

For some, the word “mummy” might evoke thoughts of the human remains displayed in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily—both intriguing and unsettling. Mummies have been discovered across the world and throughout history. Despite their diversity, they share one commonality: mummification always occurs post-mortem.

Or does it? There’s a fascinating exception to this rule. A group of Buddhist monks in Japan chose to mummify themselves while still alive. Through self-mummification, they aimed to achieve the state of sokushinbutsu (“Buddhas in the flesh”).

10. What Could Drive Someone to Do This?

The concept of self-mummification seems unthinkable. Why would anyone choose to undergo such a process?

The first individual to pursue the goal of becoming a living mummy was Kukai, later revered as Kobo Daishi. A Buddhist priest who lived over a millennium ago in Japan, Kukai established the Shingon (“True Words”) sect, a new branch of Buddhism.

Kukai and his disciples believed that spiritual strength and enlightenment could be attained through self-discipline and an austere way of life. It was common to see a Shingon monk meditating for hours beneath a freezing waterfall, disregarding physical discomfort.

Drawing inspiration from Tantric traditions in China, Kukai pushed his ascetic lifestyle to its limits. His goal was to transcend the physical realm and achieve the state of sokushinbutsu. To accomplish this, Kukai undertook extreme measures to mummify his body while still alive.

9. The Initial 1,000 Days Are Challenging

The journey of transforming oneself into a mummy is arduous and lengthy. It involves three phases, each spanning 1,000 days, culminating in a fully mummified body. For the majority of this nearly nine-year period, the monk remains alive.

Once a monk commits to self-mummification, he begins the first phase. His diet is drastically altered, limited to nuts, seeds, fruits, and berries. This strict nutritional regimen is paired with an intense routine of physical exertion.

In the initial 1,000 days, the monk experiences a rapid reduction in body fat. Dry conditions are essential for mummification—the drier, the more effective. Body fat, however, contains high water content, which accelerates decomposition after death.

Corpses with significant body fat also retain heat for extended periods, fostering the growth of bacteria that accelerate decomposition. The monk’s reduction of body fat is the first crucial step in preventing the body’s decay post-mortem.

8. The Following 1,000 Days Are Even More Demanding

The subsequent phase introduces an even stricter diet. Over the next 1,000 days, the monk consumes only bark and roots, with portions decreasing over time. Physical exertion is replaced by extended periods of meditation, leading to further loss of body fat and muscle.

This extreme emaciation is a deliberate strategy to prevent the body’s decomposition after death. Bacteria and insects are the primary agents responsible for breaking down a corpse.

Once death occurs, internal bacteria begin decomposing cells and organs. While these bacteria cause internal decay, the soft and fatty tissues of the corpse also attract flies, which lay their eggs.

Maggots emerge from the eggs and consume the decaying flesh and fat. Eventually, all soft tissue is entirely consumed, leaving behind only bones and teeth.

The monk’s severe dietary restrictions effectively remove the primary food source for these decomposers.

7. Prepare to Expel Your Insides

By the end of the second 1,000 days, the monk’s body is severely emaciated. With body fat nearly depleted and prolonged meditation replacing physical activity, muscle tissue also diminishes. Yet, the monk pushes his harsh regimen even further.

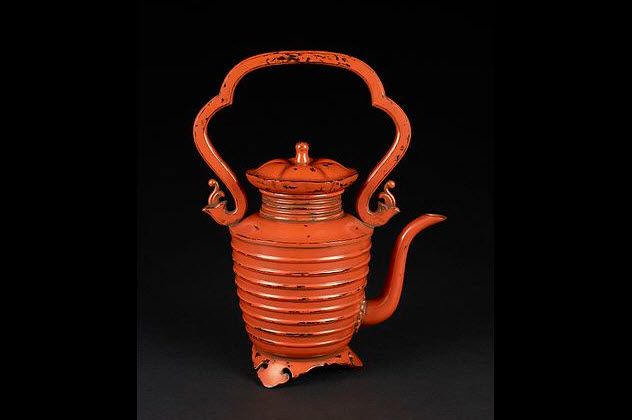

In the final stages of becoming a sokushinbutsu, the monk consumes tea brewed from the sap of the urushi tree. Typically used as a varnish for bowls or furniture, this sap is extremely poisonous.

Consuming the urushi tea induces severe vomiting, sweating, and urination, rapidly dehydrating the monk’s body and creating optimal conditions for mummification. Additionally, the toxic compounds from the urushi tree accumulate in the monk’s system, deterring maggots and insects from infesting the body after death.

6. You’ll Be Buried Alive

After enduring 2,000 days of extreme fasting, meditation, and ingesting poison, the monk prepares to transcend this world. The second phase of sokushinbutsu concludes with the monk entering a stone tomb.

The tomb is cramped, offering just enough space to sit. Its narrow walls and ceiling prevent the monk from standing or turning. Once the monk settles into the lotus position, his assistants seal the tomb, effectively burying him alive. A small bamboo tube provides minimal airflow to the outside world.

The monk remains in the dark, confined space with only a small bell for company. Each day, he rings the bell to signal to his assistants that he is still alive. When the bell falls silent, the assistants remove the bamboo tube and seal the tomb completely, transforming it into his final resting place.

5. The Final 1,000 Days

During the last 1,000 days, the sealed tomb remains undisturbed as the body inside undergoes mummification. The minimal body fat and muscle tissue inhibit normal decomposition. This process is further aided by the body’s dehydration and the presence of urushi toxins. Gradually, the monk’s body dries out and becomes a mummy.

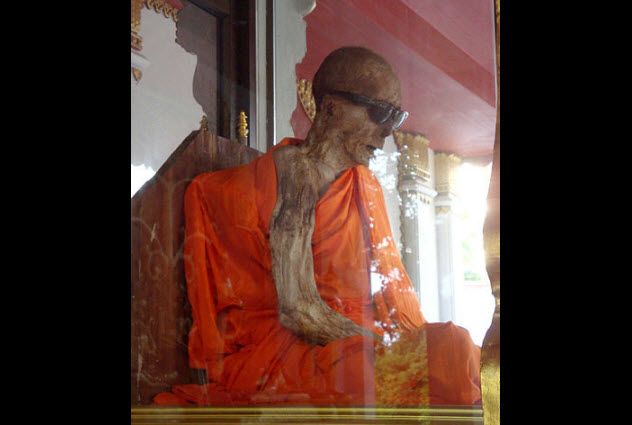

After 1,000 days, the tomb is unsealed, and the mummified monk is retrieved from his place of transformation. His remains are brought back to the temple and venerated as a sokushinbutsu, a living Buddha. The monk is honored and meticulously maintained, with priests even changing his attire periodically to ensure he appears pristine.

Whether the monk has achieved a higher state of meditation or simply passed away, he will never witness his own success.

4. The Odds of Success Are Slim

Since Kukai first introduced self-mummification over 1,000 years ago, it’s estimated that hundreds of monks have attempted the process. However, only about two dozen have succeeded, highlighting the exceptionally high failure rate.

The journey to becoming a living Buddha is fraught with challenges. For more than five years, the aspiring sokushinbutsu consumes almost no food, avoids physical exertion, and dedicates countless hours to meditation. It’s likely that only a handful of individuals possess the discipline and determination to endure such hardships for nearly 2,000 days.

Many monks may have abandoned the process. Even those who persisted until the end faced a significant risk of their bodies failing to mummify after death. The humid climate and acidic soil in Japan create unfavorable conditions for mummification.

Despite the monk’s relentless efforts, his body might still decompose within the tomb. In such instances, he would not be honored as a living Buddha but would instead be reburied. Nevertheless, his perseverance would earn him profound respect.

3. The Most Recent Buddhist Mummy

In January 2015, a new Buddhist mummy joined the ranks of the ancient sokushinbutsu. This mummified monk hailed from Mongolia and was discovered by police while being smuggled to the black market. His remains were rescued and taken to the National Center of Forensic Expertise in Ulaanbaatar.

Similar to the Japanese monks, the Mongolian monk is seated in the lotus position, appearing as though he remains in deep meditation, unaware of his death. Some senior Buddhists even claim that the monk is not truly dead, believing he is in a meditative trance on his path to Buddhahood.

Scientists, however, assert that the monk has been deceased for approximately 200 years. Regardless, this Mongolian monk benefited from an advantage over his Japanese counterparts: Mongolia’s dry, cold climate naturally aids the mummification process, unlike Japan’s humid environment.

2. The Notable Figures of Self-Mummification

While numerous monks attempted to follow Kukai’s path to becoming sokushinbutsu, only about two dozen succeeded. Some of these mummified monks are enshrined in Japanese Buddhist temples and continue to be deeply venerated by followers today.

Among the most renowned sokushinbutsu is the monk Shinnyokai-Shonin, whose remains are housed in the Dainichi-Boo Temple on Mount Yudono. Shinnyokai began aspiring to this state in his twenties and had already adopted a restrictive diet by that age.

However, he didn’t achieve his goal until 1784, at the age of 96. This was during the Tenmei famine, which devastated Honshu, Japan’s central island, claiming hundreds of thousands of lives due to starvation and disease.

Shinnyokai believed that Buddha required a profound act of compassion to halt the famine. He dug a grave on a hill near the temple and entombed himself inside. As he awaited death, only a slender bamboo tube provided him with air.

Three years later, the grave was unsealed, revealing Shinnyokai’s fully mummified body. Whether or not his sacrifice played a role, the famine eventually ceased in 1787.

1. You’ll Be Breaking the Law

The practice of self-mummification in Japan spanned from the 11th to the 19th century. In 1877, Emperor Meiji outlawed this form of ritual suicide. A new law prohibited the exhumation of graves belonging to those who attempted sokushinbutsu.

The last known sokushinbutsu is believed to be Tetsuryukai. For years, he adhered to an ascetic lifestyle to achieve mummification. When the law was introduced, his efforts became illegal. Despite this, he continued and was entombed in 1878.

After the final 1,000 days passed, his followers faced a dilemma. They wished to open the grave to verify Tetsuryukai’s success but feared imprisonment. Under cover of night, they exhumed Tetsuryukai and discovered he had indeed become a mummy.

They aimed to display their new Buddha in the temple. To avoid legal consequences, Tetsuryukai’s followers altered his death date to 1862, predating the law. Today, Tetsuryukai remains enshrined at Nangaku Temple.